Let this be the moment the phrase “Klassen eyes” was coined. Whether a bear’s or a boy’s, on a fish or a dog or a duck, the eyeballs Jon Klassen straps onto his characters put in a lot of work. “Jon conveys such profound emotion by just moving pupils around,” says his longtime friend and collaborator, writer Mac Barnett. “He moves them and gets operatic emotion.” Emotion and then some, as if he’s opened up a channel between the eyes and the action. Klassen can fold an entire plot into a look.

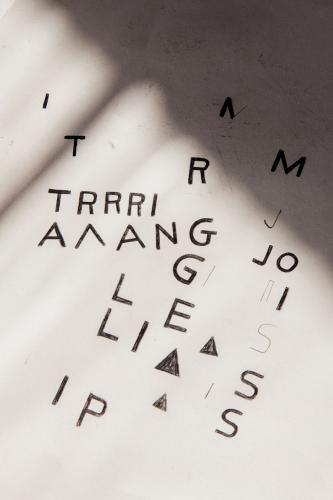

You can see it in his hat series (This Is Not My Hat; We Found a Hat; I Want My Hat Back), and in The Wolf, the Duck, and the Mouse, which was written by Barnett. But the eyes are there in spades in Barnett and Klassen’s latest project, a trilogy based on three shapes as characters—Triangle, Square, and Circle—a project that, in all its simplicity, might well be their most complex so far.

Triangle, Square, and Circle were originally conceived as characters for a video game Klassen was designing while working in animation, where the storyline included whole civilizations of simple shapes. In 2015, he and Barnett returned to the shapes concept to see if it might work as a book. “We started talking about narrowing it down to one book for each shape and getting really elemental with the storytelling,” Barnett says. “Minimalism with both image and, to some extent, the text.”

In many ways, the picture book is already a distilled form—lean but packed. To strip it down even further led them to reconsider certain fundamentals of storytelling, character among them.

“I’ve always had a problem with character design in animation,” Klassen says, “and even for books, where characters are designed for what they should do in a story. When a hero has to be a hero, you draw them that way, so that the reader knows what to expect. Villains are the same way. It’s problematic for a bunch of reasons, because you’re pulling from features that feel evil visually—and what the hell is that? It was paint by numbers, and you were just picking from a list of evil or handsome features. It felt boring.”

What makes the shapes attractive, Klassen says, is that their features are so simple as to be almost antithetical to that idea. And yet “even the small changes I had to make for them ended up clueing us in to their personalities. Triangle’s eyes had to be moved down because there’s less room at the top, and so he looks shiftier, and Square’s eyes are right in the middle, so he ends up looking stronger—but possibly more vulnerable in certain moments. And then Circle ends up looking kind of Zen. And all those things were pulled out of the way they look when you put eyes on them. I suppose you could argue that it was, in fact, a study in how character design is actually very important. It’s a funny thing: I spent all that time avoiding characters, and then it turns out that, well, it is the eyes. But it’s the eyes with context.”

The plots of this shape trilogy are simple: Triangle plays a prank on Square; Square tries to sculpt Circle’s likeness; all three play a game of hide-and-seek that gets a little messy when Triangle breaks the rules. Within those simple narratives are the subtexts and subtleties that elevate all great picture books. But what surprised Barnett and Klassen was the degree to which improvisation led them through these stories, with the personality of each shape evolving in ways they hadn’t expected—in a form that isn’t always forgiving of uncharted territory.

“Picture books are really hard to improvise because they’re such precious, singular things,” Klassen says. “You don’t have much room to wiggle around. They always feel like they have to justify their existence inside thirty-two pages. So the temptation to make something that feels tight and considered and calculated is always there, and it’s really hard to be loose. That’s part of the reason this is a trilogy, and also why it’s so clean visually: As long as the characters and the world feel on brand, for lack of a better term, you’re able to wander off in different directions narratively.”

And yet the wandering, too, seems to have a kind of precision to it. “The text paces it,” Barnett says. “It tells you how long to spend on each page. It gives that rhythm, that build, whether we’re moving staccato or drawing things out.”

There is a point at which things get a little intense—in Circle, with its big mystery of an ending that is both slightly haunting and philosophically rich. The eyes (again) do most of the heavy lifting, while the rest of the energy comes from what’s unsaid. It is a literary moment unique to the picture book, reminding us of its maturity and innovation and how the best ones honor the largely underappreciated sophistication of their audience.

There is a point at which things get a little intense—in Circle, with its big mystery of an ending that is both slightly haunting and philosophically rich. The eyes (again) do most of the heavy lifting, while the rest of the energy comes from what’s unsaid. It is a literary moment unique to the picture book, reminding us of its maturity and innovation and how the best ones honor the largely underappreciated sophistication of their audience.

“Kids of picture-book age are some of the most flexible, brave, catholic readers you get,” Barnett says. “They’re much more likely to take a risk on a piece of literary or experimental fiction than adults are.”

“They can understand when they’re being given an exercise in style, or when they’re being given a product of some true affection for the work,” Klassen adds. “And that seems to be the common denominator through all the successful books, even if they don’t line up aesthetically or politically. Kids just understand when you’ve turned something on—they just get it. That’s what excites them. You’re not trying to fake it for them—they’ll sniff that out right away. But they can understand through the work itself that you’re really into it.”

— Paul Reyes