A man and a lion once found a stone statue depicting an athlete strangling one of those giant cats. The man said, “We humans are the strongest creatures on earth!” The lion answered, “If we lions could sculpt, the statue would tell an entirely different story.”

Thus a fable from Aesop, a manumitted Greek slave who told stories about animals and their ways. Those stories had sharp points. Aristotle credits Aesop with defending a corrupt politician by telling the story of a hedgehog who, pitying a flea-infested fox, offered to pick off the vermin with his quills. The fox replied, “These fleas are full of blood. They no longer bother me. Remove them, and fresh fleas will come.” In other words: Oust the politician, and another will rob the city.

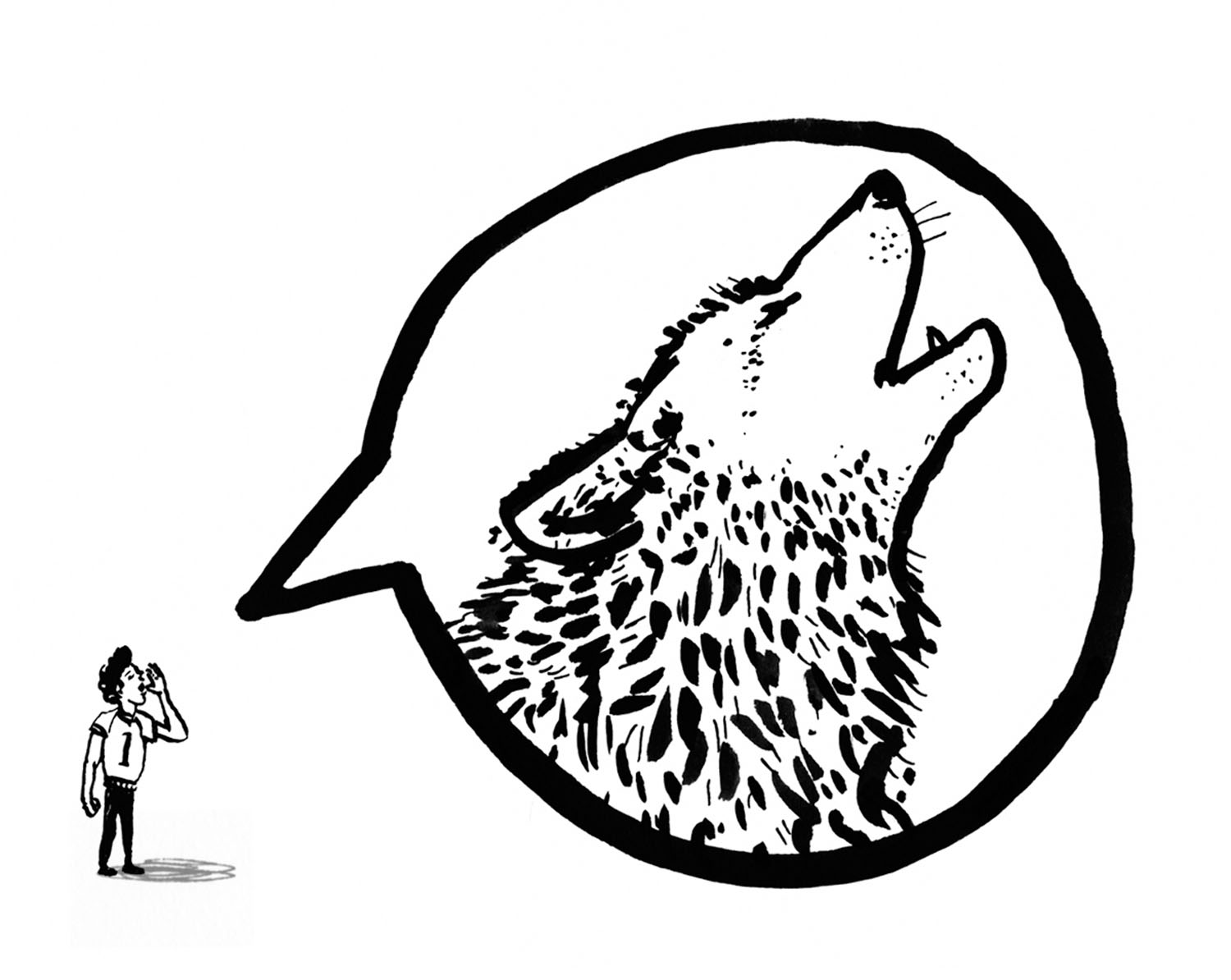

All animals communicate. Our species is the only one that can tell stories, using nested sentences full of conditionals, counterfactuals, futurity. Human language enables us to lie, without which—well, let’s turn this over to Vladimir Nabokov, who opined that literature was born when, in another Aesopian story, a boy cried wolf when there was no wolf at his heels.

The fable is the Ur-type of all storytelling, in which animals (and sometimes plants, usually trees) exemplify desired norms of human behavior. Ants store food for the winter and tortoises place first in races meant for hares to win: Such stories teach us foresight and perseverance. Foxes complain about sour grapes and wolves chide dogs for slavishness: Such stories teach us to set realistic goals and cherish freedom.

Similarly, fairy tales are meant to teach children norms of behavior. But they do so in a different way: Befitting the dark woods where the Brothers Grimm wandered, collecting folk stories from people inured to plague and war, fairy tales often use monstrous characters to illustrate the many ways in which people can be horrible to one another: grinding bones to make bread, putting princesses to sleep for centuries with witchy potions, things calculated to frighten young listeners into towing the line. In a world full of ogres and witches, even fairies are scary.

Throw in a god, and you enter the realm of myth: stories in which divine beings work their wiles, with or without humans in view. Put a human, known or presumed, as the lead in such a story, and you have a legend: George Washington and the cherry tree, Saint George and the dragon. Fable, fairy tale, myth, legend: Each is a species in a literary genus that tells us why there are stars in the sky, why spiders spin webs, how fate tangles our plans, how to be human. We tell, we have always told, such stories to explain things—and to keep ourselves safe against things that go bump in the night.

In the end, that last bit never really works: We brave dangers, and we die. We tell our stories, and we pass on. But the stories endure. They are what make us human, no matter the form in which we tell them.