Sleepwalking terrifies me. With zombies, at least, it’s clear that the person inside the body is lost. The sleepwalker, however, occupies a space where agency and identity become blurred, where one might act like a sloppier version of oneself (see: sleep cooking, sleep driving) or in ways profoundly different from who one is (see: sleep sex with strangers, sleep murder!). It’s a phenomenon, as Dr. Rosalind D. Cartwright states in The Twenty-four Hour Mind: The Role of Sleep and Dreaming in Our Emotional Lives, that is difficult to study, not only for the logistical challenge of hooking up a sleepwalker in a lab, but for the famously mysterious terrain of the unconscious.

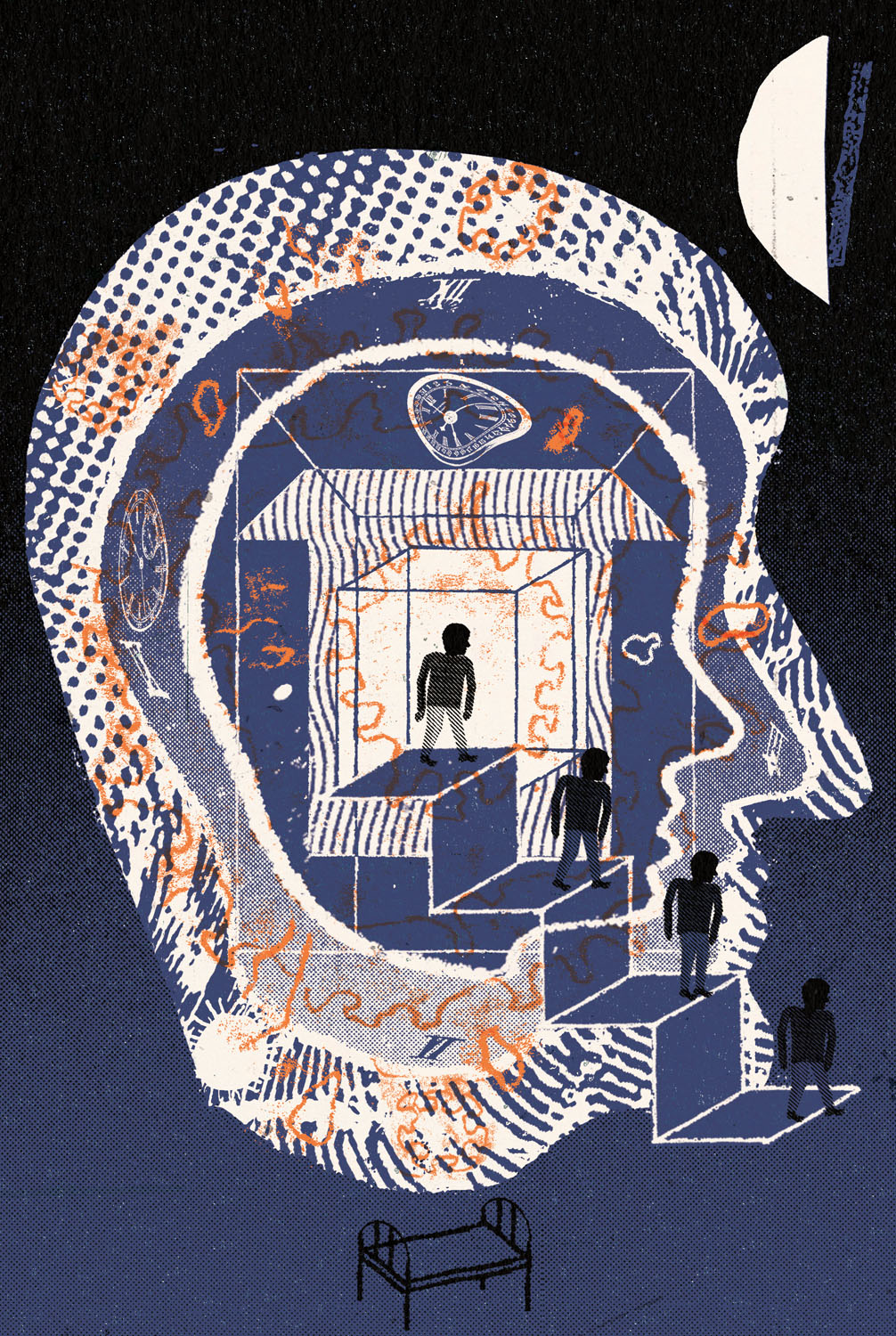

As far as I know, I have not been, and am currently not, a sleepwalker. As a writer, I’m drawn to sleepwalking for its unknowability—not just to me but to sleepwalkers themselves. During sleepwalking, Cartwright says, “unconscious motives are driving physical behavior without consciousness…and without memory of the event after waking consciousness returns.” I imagine the sleepwalker who goes to bed and wakes up on their front lawn, in their car, or standing in front of a burning stove will ask themselves what happened, what it means. Structure follows experience; as with dreams, we apply the reading retroactively.

So it can be with stories. In her memoir, The Shapeless Unease: A Year of Not Sleeping, Samantha Harvey suggests that writing, rather than drawing from the subconscious, “is the subconscious, and it draws on the conscious.” For me, writing feels most alive when I reach that fleeting dreamlike state in which I forget, if only for the breath that it takes to finish a sentence, that I am writing at all. Yet writing is also an act of constraint: The sentences lasso the intangible into a tangible form. Hence the use of metaphors—like sleepwalking itself, employed not only in this essay, but in our attempts this year to make sense of our reality. Is this actually happening? Someone please wake me up. Maybe this is one of the guiding rhythms of life: The inexplicable happens, so we make it explicable.

In The Fall of Sleep, the French philosopher Jean-Luc Nancy writes, “Just as night represents a time of cosmic rhythm and sleep a time of biological rhythm, so also does sleep compose in itself the rhythm in which its profound nature is reflected.” We find such rhythms before we enter sleep, by singing lullabies and rocking babies. We find them in the way we exit sleep, swinging from the haze of dream to the plain crush of light through our windows. Our adherence to this rhythm allows us to dream a ghost and wake up relieved, as Borges once stated, referencing Coleridge. To dream a ghost while still awake is another matter.

During the early weeks of lockdown in the States, we may have seen our fair share of ghosts. From the eerie photographs of a vacant Times Square to the teary-eyed man crouched outside a bedroom window, meeting his grandchild for the first time, we might have processed these images by thinking of ourselves as living in a story about a global pandemic. We might have called this story surreal, even as events insisted otherwise. In February and March, the killings of unarmed Black Americans remained so precedented that news of Ahmaud Arbery’s and Breonna Taylor’s deaths did not capture national attention until months later. Meanwhile, the pandemic exposed the inequity long baked into our economic, housing, and health-care systems, harming Americans at disproportionate rates along class and racial lines. George Floyd, it turns out, had lost his job due to the pandemic and contracted coronavirus before his death.

In all this time, we have somehow continued to sleep, albeit poorly for many of us. To sleep is to relinquish our need to protect ourselves and those we love from danger, which is easier to do when there is less to relinquish. But sleeping badly, of course, is still sleeping. “Sleep itself knows only equality,” Nancy writes, “the measure common to all, which allows no differences or disparities.” To be awake, then not awake: Is this our most dependable rhythm? There’s something off about survivors in post-apocalyptic movies never yawning. Our desire to sleep conquers even our desire to live.

In The Shapeless Unease, Harvey frames her insomnia as a daily cycle of violence: “I go up to bed at night, I get beaten up, I come downstairs in the morning. Then I go about the day as if things were normal and I hadn’t been beaten up, and everyone treats me as if I hadn’t been beaten up.” How else to write about an ordeal like this but in the passive voice? The perpetrator is nameless, formless, creeping between the self and the outside world. Unlike fear, insomnia isn’t a response to danger, as Harvey explains. It is being afraid of insomnia that invites the danger.

Those of us who can sleep fall into it, the way we fall backward into the arms of someone who we know will catch us. We might be troubled by our thoughts before falling, but in falling, we let go. For Harvey, however, the prospect of not sleeping creates a “heaviness of predictability,” in which trying to sleep transforms into a nightly act of thinking about how she can’t sleep. If she were to fall backward, there wouldn’t be anyone to catch her, even as she never hits the ground—a nightmare version of a trust fall, though to escape into a nightmare might be preferable. The Shapeless Unease chronicles Harvey’s private and public griefs in 2016, but its resonance in 2020 is palpable: We found ourselves more alone with our thoughts—our fears—as new and perverse rhythms came knocking.

Perhaps one of these new rhythms was a conflation of previous rhythms. Rather than moving from sleeping to waking, or waking to sleeping, our experience of the two can feel simultaneous. I asked Dr. Tang Kuang, a sleep-medicine specialist in Dallas, Texas, if he had noticed any shifts in patients’ sleeping patterns this year, and he described a case in which a patient with mild depression reported not sleeping for multiple nights in a row. The strange part was that during the day, she did not feel sleepy—worn out, but not sleepy. After monitoring the patient in a sleep study, Kuang found that she was in fact getting a full night’s sleep—it was only that she perceived herself to be awake, even reporting that she did not close her eyes. “This is a phenomenon we call sleep state misperception or paradoxical insomnia,” Kuang says, “which can be caused by multiple factors: depression, anxiety, alcohol, certain medications, social isolation, a disruption of sleep schedules.”

A person who suffers from paradoxical insomnia tends to experience unusually long periods of rapid-eye movement (REM) sleep or remember only awakenings from REM sleep, in which dreams are more vivid and intense. If one were to wake up remembering the distinct details of a dream—say, that one had been wading through a field of cheesy mashed potatoes, naked—then this person, this hypothetical person, would probably be remembering a dream that came out of the REM stage. “If people have more REM sleep, they can feel like they hardly slept at night, because their brains have been more active,” says Kuang. “But actually, they have been dreaming all night long.”

For the paradoxical insomniacs among us, the mind at work does more than remember: It confuses itself, forgetting that during those longer periods of non-REM sleep, or “deep sleep,” it was at rest. The restless, working mind produces a memory of an actual dream that feels like the memory of a daydream. So we go through our day, believing that we’ve been thinking all night instead of sleeping. If only we could stop thinking and let go, we tell ourselves. But to let go is to fall—to fall into another way of thinking. The work never ends.

Unlike dreaming, sleepwalking occurs during the non-REM stage. A sleepwalker won’t feel as if they have been awake, because their brain, the source of such feelings, has been asleep. When the outside world is such that it may be easier to burrow into our minds, I can see how sleepwalking, even metaphorically, can seem attractive. But surely it is unsettling too—the idea that sleepwalking could sneak into one’s nightly ritual and escape undetected.

Sleepwalking subverts the belief that what we touch must be felt. Waking up, the sleepwalker would likely want to know where the sharp pain on their forehead had come from, or why there was dirt from outside caked to the bottoms of their feet. Touch keeps us grounded. It validates what we see, hear, smell, or taste. Our fingertips, in translating that touch, tell us a story about our bodies and the spaces they move through. Without touch, or even the proximity of touch, it’s fair to ask how that story is changing.

On a screen, are we seeing the act of seeing more than what is being seen? Are we hearing the act of hearing more than what is being heard? It’s a question that could have been posed pre-pandemic, to the ways that we compartmentalize and distance ourselves from people we don’t know. We could rightfully call this ignorance. We could also call this, at times, “taking a breath.” All judgment aside, this year the same act of distancing has become more common when interacting with people we do know. People we hold closest. People we can’t hold close. People who, in our distancing, no longer feel as close.

But maybe there is another way to think about touch. It’s not always a bridge, to be sure—excessive and unwanted touch constituting a form of violence. But when touch does intend to act as a bridge, we might look under the bridge, feel the shakiness of its foundations beyond the physical plane. “Sublime imagination touches the limit,” Nancy writes, “and this touch lets it feel ‘its own powerlessness.’”

In a year marked by an overwhelming loss of agency, we’ve let our imaginations barrel forward, sometimes into genuinely dangerous territory, as with the embrace of QAnon conspiracy theories about a “deep state.” When weaponized in desperate times, imagination can impede the progress that it first made possible. That one of the most imaginative acts might be to imagine the limits of what one can imagine—for me, as a fiction writer, it’s an idea that actually offers comfort.

A few blocks away from my apartment in Tulsa, Oklahoma, three weeks after the ninety-ninth anniversary of the Tulsa Race Massacre, one day after Juneteenth, and at the end of a week that marked the highest number of COVID-19 cases up to that point in Oklahoma, President Donald Trump held his first (indoor) rally for his reelection. When criticized for his choice of location and date—the rally had been originally scheduled for Juneteenth itself—Trump backpedaled. He would move the rally back one day, he tweeted, “out of respect for this Holiday.” But even if the initial scheduling of the rally was not an intentional racist dog whistle, what does it say that the president was able to imagine, in the middle of a pandemic, a sold-out rally where thousands of unmasked supporters would spill out onto the street, but not that the rally would be perceived as disrespectful given the history of a still-segregated Tulsa?

“The subject of the dream is the dreamer,” says Toni Morrison. I thought of this the day of the rally, when word spread that Vice President Mike Pence, along with Oklahoma governor Kevin Stitt, planned to tour the Greenwood District and various sites of the 1921 race massacre. In response, local Black activists covered the memorials near the Greenwood Cultural Center with tarp and taped signs over them: this is sacred ground—not a photo op. $2,719,745.61 of unpaid claims remain unpaid. reparations now. Here was a community that refused to be the subject of Pence’s public-relations fantasy, returning the gaze instead.

Who gets to see and who is forced to be seen? If this were happening virtually, I thought, the vice president would be the only one with his video turned on, searching the blocked boxes for someone, anyone. Instead, he sees only himself, seeing himself.

What Pence would see, later that night: Trump wrapping up his rally, in front of mostly empty seats. What he would not see: more than a thousand Tulsans gathered for a joyous block party a mile away in Greenwood; cars parading, plates buzzing with bass, past Vernon A.M.E. Church, the only Black-owned building still standing on the original Greenwood Avenue; children riding on sunroofs, fists raised; protesters from the rally arriving to cheers, I-244 bending overhead—a highway which, when it was built in 1975, tore through a rebuilt Greenwood, stunting redevelopment; a Black Lives Matter mural, freshly painted in big, bold yellow (soon defaced with blue paint, then ordered removed with the support of a mayor who’d done nothing to stop Trump’s rally, and reelected afterward). Neither Trump nor Pence would see any of the celebration, how this celebration could take shape in the midst of despair, how it could be used against despair. And in Kenosha, Wisconsin, in September, when Trump would visit and not once utter Jacob Blake’s name, he would not see another party forming at the site of Blake’s shooting: bounce houses, laughing children, COVID testing, voter-registration booths, music and dancing in the streets, the scent of hot dogs on the grill, as if summer refused to end.

To be awake. To be present. To be there while another sleeps, bearing witness to their sleep. I think of Dr. Kuang’s patient, how it took another person to see her sleep in order to tell her that she was, in fact, sleeping. We need others to tell us what happens after we close our eyes, to anchor us as we drift away. Such companions may see us more clearly than we see ourselves.

I think also of how we sleep together, whether on a single bed with a lover, or in tandem with a home, a street, a neighborhood, a community, a city, a country—how we participate in a collective surrendering of defenses, which Nancy likens to “boats moving off to the same open sea, to the same horizon always concealed afresh in mists.” I risk being sentimental about sleep, but it’s hard not to be. In sleep, we don’t know where we’re headed, yet we go there all the same. It is an act of radical vulnerability inherent in who we are.

Perhaps this speaks to why the dying, embarking on their final sleep, can so trouble the living. In War and Peace, a dying Prince Andrei experiences in his final days an “awakening from life” that brings forth an “estrangement from everything belonging to this world.” To Princess Maria and Countess Natasha, both of whom adore him, it feels as though they are no longer attending to Andrei, but to “what remind[s] them most closely of him—his body.” Yet they stay by his side, because this is what we do across time and space: We participate in the ritual of witnessing, striving to “touch” the unknown. “Our vigil opens a rhythm between the living and the leaving,” Nancy writes. “It inscribes their departure in counterpoint to our vigilant presence.”

That the coronavirus pandemic has forced so many of its victims to go into their final sleep alone feels like a violation of a sacred ritual, multiplied on a global scale. But maybe one doesn’t have to be in the room to hear what the dying are saying. Technology, too, has multiplied the scope of bearing witness—especially during times like these, from the early WeChat warnings of Li Wenliang, the “whistleblower” doctor in Wuhan, China, who died from the coronavirus, to the relentless footage of police brutality in the United States. Then again, one’s ability to bear witness has never required a video either.

When you look up at the night sky, Harvey writes, “what you see is the immense nothingness between stars, and you see how nothingness is a condition for somethingness.” I wonder if witnessing, then, is partly our conscious and unconscious delineating the “somethings” against a backdrop of “nothings.” Which is itself a story we tell ourselves, because one could argue that everything, including the darkness between the stars, is a “something.” We can’t possibly name all that we encounter, but we stop to discern forms in the darkness all the same. Maybe this is a precondition to being awake.

It’s the ones who are awake who can discern, among other forms, the sleepwalkers. The waking can name the act of sleepwalking, while the sleepwalker remains adrift. The waking are also the ones most often disturbed by sleepwalking, their fear not unlike that of Princess Maria and Countess Natasha as they watch a dying man who, in his straddling of two realms, appears to them incomprehensible. Contrary to the way sleepwalking is used in news headlines, as shorthand for a subject’s passivity or lack of awareness, the phenomenon is a complicated collision of genetics, surrounding triggers, lowered slow-wave activity, heightened cerebral blood flow, and other factors difficult for the waking, often guided by frameworks of cause and effect, meaning making, and linear time, to process.

I can only ever understand sleepwalking from a distance, and it is precisely for that reason that it feels to me an apt metaphor for this year, as we continue to move through the muddled boundaries of inside and outside, essential and nonessential, something and nothing, safety and danger, beginning and end. We move through time that feels indefinitely suspended, time as we might experience it in poetry—what A. Van Jordan compares to the “fermata” musical notation. As a country, it’s not clear where we are headed, or even in which direction. When states first reopened in May, many treated this as a sign that we had returned to normal. And in a way, we had: Forests and homes continued to burn, voters continued to be suppressed, billionaires continued to get richer. Meanwhile, the virus never went away, colleges and bars and gyms opened only to close again (only to open and close again), and the stories we told ourselves about this year became so messy they simply became our lives.

I put the finishing touches on this essay on November 7 knowing that the future as I describe it will seem misestimated, irrelevant, or will, in one way or another, seem pale by comparison to what actually is. There will be relief and hope and change and probably violence. The country will look different, but not always in ways that many of us would like to believe. Many people who voted for the new president may in four years reverse course, pinning their hopes on the newest iteration of the old president. What is old and what is new, we will wonder. What does it mean to be here, now?

To be awake. To be present. In The Twenty-four Hour Mind, Cartwright says that sleepwalking is more likely to occur when we go to sleep in a new place, an unfamiliar bed. Sleepwalkers can’t recognize faces. They don’t remember their own actions, only feelings—most commonly, that of fear. Is this actually happening? When we say this, awake to it, perhaps we mean not only that the world has become strange, but that we have become strangers to ourselves.

For a long time, our conscious and unconscious will work concurrently to create yet another new reality. Some of us will see flashes of the familiar and return to the most seductive dream, one which the lucky few lived in prior to 2020, one in which danger was well outside the neighborhood, or at least our neighborhood. Or, if danger was nearby, that we could wake up from and say it was all just a dream. The advice to never wake a sleepwalker, uttered as far back as nineteenth-century Italian operas, is often misunderstood. It’s not that you’ll harm a sleepwalker by waking them. It’s that the sleepwalker, not recognizing which reality they’re in, may see your presence as a threat. That if they are awakened they may become confused, frightened, even angry. Take me back, they might say, not knowing where they were to begin with, and certainly not at ease with where they are.