Has there ever been a disease so intensely studied and so intensely controversial as Coronavirus Disease 2019? We have come to know more more quickly about COVID-19 than we have about any pandemic-causing pathogen in history. The genetic sequence of the novel coronavirus was uploaded to an open-access database by scientists from the Shanghai Public Health Clinical Center on January 11, 2020. Within two days, scientists at the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland, and at Moderna Therapeutics in Cambridge, Massachusetts, used the sequence to create the blueprints for a vaccine that would be delivered into people’s arms in just over a year’s time. The effort was part of the US government’s “Operation Warp Speed,” and led to what was considered “the fastest vaccine ever developed.” Remarkably, according to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the mRNA class of vaccines was also found to be 94 percent effective at preventing symptomatic COVID-19 infection in pre-variant trials, with a relatively low risk profile. With these and other therapeutic breakthroughs, we now have precisely the kind of treatments that, as Susan Sontag argued in her seminal book, Illness as Metaphor, lead to the demystification of disease.

Has there ever been a disease so intensely studied and so intensely controversial as Coronavirus Disease 2019? We have come to know more more quickly about COVID-19 than we have about any pandemic-causing pathogen in history. The genetic sequence of the novel coronavirus was uploaded to an open-access database by scientists from the Shanghai Public Health Clinical Center on January 11, 2020. Within two days, scientists at the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland, and at Moderna Therapeutics in Cambridge, Massachusetts, used the sequence to create the blueprints for a vaccine that would be delivered into people’s arms in just over a year’s time. The effort was part of the US government’s “Operation Warp Speed,” and led to what was considered “the fastest vaccine ever developed.” Remarkably, according to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the mRNA class of vaccines was also found to be 94 percent effective at preventing symptomatic COVID-19 infection in pre-variant trials, with a relatively low risk profile. With these and other therapeutic breakthroughs, we now have precisely the kind of treatments that, as Susan Sontag argued in her seminal book, Illness as Metaphor, lead to the demystification of disease.

The question on everyone’s mind, now that hopes for achieving herd immunity or COVID-zero have vanished, is how do we get enough people vaccinated to reduce hospitalization and death from the virus? Data has been bandied about to help people see the scope of the problem and the usefulness of the injections. But data alone doesn’t seem up to the task of dissolving misconceptions. According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, “Trust in government sources of information is especially low among those who say they will ‘definitely not’ get the vaccine.” That mistrust has been compounded by conspiracy theories trafficking in a similar valence of misinformation. As an Economist/YouGov poll found in May 2020: “Three in five vaccine rejectors believe that infertility (62%) or changes in a person’s DNA (60%) could occur with the vaccination.” Half of those surveyed thought the vaccine caused autism; half also thought the vaccine included a microchip. Unsupported beliefs, all.

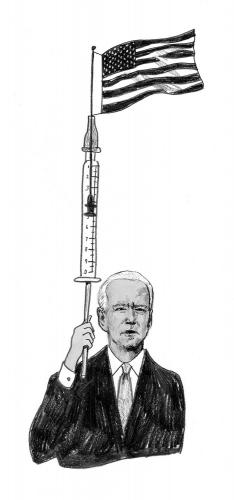

So, in addition to data, and in keeping with the traditions of public rhetoric, political leaders and scientists turned to metaphor. Back in March, President Joseph Biden enlisted the language of patriotism, tethering the quest for vaccination to the idea of national independence. “After this long, hard year,” Biden said, “[getting vaccinated] will make this Independence Day something truly special where we not only mark our independence as a nation, but we begin to mark our independence from this virus.” As we now all know, despite remarkable progress, the nation fell just short of Biden’s goal of having 70 percent of adults vaccinated with at least one shot by the Fourth of July (though it should be noted that rates of vaccination among those over age sixty-five is admirably high in some states).

Is it possible to understand the persistent lag in vaccination rates as a function of failed metaphor? That is to say, as a failure of language—the language of data, the language of science, the language of political rhetoric (to name just a few vocabularies)—to meet individuals at their particular coordinates on the social map? The virus and our national response to it has been figured and refigured. Yet the hardcore hesitant remain skeptical, if not obstinate. How much is this a function of a particular metaphor’s limitations, versus the social limits of metaphor in general? These questions aren’t meant to undercut real concerns about structural inequities that govern resources and access to vaccines, but they are designed to expose subtler barriers that exist alongside these undeniable realities.

Before trying to answer such questions, though, it’s useful to look beyond the high stakes of the current pandemic toward the way clinicians regularly use metaphor to translate medical concepts for their patients. Antibody-antigen binding, for instance, is often equated to a “lock and key” when trying to explain how routine immunizations work. Herniated intervertebral discs are called “leaky jelly donuts” in the lead-up to spine surgery. The heart is constructed as a “pump” and our arteries and veins as so much “plumbing,” especially before a cardiac catheterization. Metaphors prevail on the microscopic level as well. Pathologists commonly describe the cells on their slides with terms like “leaflike,” “honeycombed,” “moth-eaten,” “tombstone-patterned.” And radiology is full of its own figurative language: “sandwich-vertebral body” (seen in a type of degenerative bone disease) and “boot-shaped heart” (for a kind of congenital heart malformation), for example. These are practical gestures. Considering the gulf between patients and the hyperspecialized language of the medical sciences, it isn’t surprising that, as one study found, physicians who use more metaphors were perceived as better communicators by their patients. Metaphor binds together the physician and the patient. And this makes sense from the patient’s perspective, given people’s desire to understand their diagnoses and their options.

But metaphors don’t abound in medicine just because they’re powerful tools for explication and persuasion between patients and doctors. On a more fundamental level, science relies on metaphor for its legitimacy. It’s often asked: “How much can science explain?” Or, put in the negative: “Is there anything science can’t explain?” When the layperson is the intended audience, the answers to both questions depend on how well science can metaphorize its findings. Without metaphor’s bridges, science would languish—unrecognized, misunderstood, unheeded.

Medical metaphor, then, is driven not only by the desire to communicate, but by the need for social credibility as well. The more complex the scientific models and methods, the more difficult it is to translate them with fidelity at a socially digestible scale. And so scientists and doctors must articulate ideas that meet people where they are in order to steer them from the known to the new. To achieve this move, a metaphor must be recognizable as part of a common narrative about the world while also being capable of effecting conceptual change within that narrative. In seeking this kind of acceptance and incorporation, users of medical metaphor not only replicate understanding for patients, but also solidify their own authority. A metaphor that nobody accepts is, after all, merely a fantasy without a function.

The legendary physicist Steven Weinberg was hopeful about science’s ability to explain almost anything except itself. “It seems clear,” he said, “that we will never be able to explain our most fundamental scientific principles…I think that in the end we will come to a set of simple universal laws of nature, laws that we cannot explain.” The implications of this quixotic pessimism raise another question: If science can arrive at laws that are both universal and untranslatable, can such laws ever be truly universal? Of course, gravity exerts its influence regardless of our assent or understanding: The apple always falls from the tree whether we understand gravity as a fundamental Newtonian force or, as Einstein would later repostulate, as a curvature of time and space caused by mass and energy.

The history of science is full of these kinds of dramatic redescriptions of natural phenomena. Recognizing this can help us see scientific theories as interpretive models in competition with one another. Rather than being fixed or immutable, these descriptions evolve as our questions about the world evolve. New questions necessitate new concepts and metaphors, which in turn demand and enable new ways of being in the world. In literature and in science, metaphors seek to embody what is, literally, beyond reach. In poetry, metaphors are used to help us experience—viscerally and otherwise—that which we cannot access directly. Likewise when studying the phenomenal world, scientists use metaphor to pursue knowledge that usually cannot be accessed straight through the senses. Galileo developed a technique of his own when he sought quantitative answers to a pair of questions that didn’t occur to Aristotle: Namely, why do objects speed up as they fall? And can we predict the position of an object at any given point along its path of motion? To answer these questions, Galileo recognized that his senses alone would not be up to the task, so he turned to a new concept: acceleration. “Galileo used the term acceleration as a metaphor to describe the change [in] speed over time,” mathematician David Deriso argues. Although Galileo could never literally “see fast enough to quantify acceleration,” he was “clever enough to encode the concepts he could not measure or sense into ideas he could work with.” In this way, Galileo utilized a metaphor to understand an experience that resisted direct access despite being right in front of him.

Notwithstanding its pervasiveness in scientific methods, metaphoric thinking faces major hurdles when it comes to national public health policy, which must necessarily be deployed by bureaucracies at a distance from which it is often difficult to combat what Sontag, referring to AIDS, called the “phantasmagorical, symbolic”—a meaning that the coronavirus itself has acquired. Take, for example, the Kaiser Family Foundation’s findings that county-by-county partisan makeup is “one of the main factors driving differences in COVID-19 vaccination rates.” Kaiser found that not only is there a partisan gap in vaccination rates, but the gap quintupled from 2.2 percent in April to 11.7 percent in July, with lower vaccinations in counties that voted for the forty-fifth president. Ideology appears to skew perceptions of COVID-19 risks on both ends of the political spectrum, according to a survey by Franklin Templeton-Gallup. Democrats were more likely to overestimate COVID-19 hospitalization rates and COVID-19 child-mortality rates, whereas more than a third of Republicans incorrectly believed that asymptomatic COVID-19 transmission was impossible, and that COVID-19 killed fewer people than influenza and automobile accidents.

This past summer, the US Surgeon General, Vivek Murthy, identified COVID-19 misinformation as a major obstacle to achieving vaccination goals: “The problem right now is that the voices of these credible public health professionals are getting drowned out,” Murthy said. In some states, those credible voices were even silenced. As a possible sign of pandemic-response politicization, Kaiser Health News and the Associated Press report that almost two hundred public health experts in thirty-eight states resigned, retired, or were fired between April and December of 2020. Those who’ve stayed in their positions have confronted unprecedented levels of backlash.

If, as Sontag argues, disease typically becomes less symbolic as it becomes more treatable, why has metaphor and perceptual distortion clung ever more closely to COVID-19 the more preventable it has become? I put this question to Raúl Necochea, a medical historian at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. “It’s relatively new in history for science and medicine to have so much unified cultural authority,” Necochea told me. Prior to the 1930s, it was rare for biomedical narratives to be widely and definitively accepted. The great therapeutic revolutions became a part of popular discourse relatively recently, with sulfa drugs introduced in 1935 as the first successful antibacterials. Penicillin itself only became widely accessible to the general public by the 1940s, after first being used in World War II to treat battlefield infections. Likewise, seismic (and reliably reproducible) surgical innovations only came to fruition in the early twentieth century. With these curative advances in medicine there began a rapid tapering of the discourse around illness, with bioscientific narratives claiming increasing authority. For Necochea, it was “historically surprising…to see such relative dominance, so quickly.” The fact that medical narratives could contend with, let alone safely coexist alongside, religious and popular approaches to illness was extremely unusual. The problem, Necochea pointed out, is that some practitioners in the West “may have bought into the idea that biomedical authority is incontestable,” even though this wasn’t the case for most of human history. “How did we get so confident about ourselves in such a short amount of time?’’

Perhaps it is this confidence that partly informs the incredulity of those who desperately urge the unvaccinated to “trust the science” or, more pejoratively, who label the vaccine-hesitant as “covidiots.” Although vaccine resistance is certainly a far greater problem than name-calling, vaccine advocates may do well to remember that rhetorical ownership of an illness is not always a settled matter, as the critical mass of the unvaccinated population, unswayed by the mounting body count, proves. Instead of expecting scientific data to “speak for itself” or for the increasing availability of effective treatment to lead to what Sontag calls a “de-dramatization” of the disease, we must see these problems—one of developing remedies for the biological phenomenon of SARS-CoV-2, the other of actually deploying those remedies in a socially meaningful way—as equally important. It’s this latter struggle that now hinders the pandemic effort in many regions of the United States. Our ability to overcome the biological pandemic is inextricable from our ability to master the language we use to describe it.

Public health practitioners like Rhea Boyd have consistently argued for this kind of socially conscious engagement, seeing the unvaccinated not as “a monolith of defectors” but rather as people with legitimate questions. It’s important to recognize the perspective of those who’ve been historically mistreated by institutional medicine or who lack the resources to be vaccinated. Doing so, Boyd argues, “requires daily acts to dispel and decrease the rampant disinformation people are contending with.” One such form of disinformation is fueled by the underlying mechanics of viral physiology itself: As the virus replicates, it mutates—and as those mutations accrue, the virus has the potential to make functional gains that break through the firewalls provided by vaccination. The delta variant mutations, for example, result in a one thousand-fold increase in viral load in the respiratory tracts of infected people, aiding transmission earlier and more efficiently through a population. Although vaccinations remain extremely effective in preventing severe disease and death from the delta variant, the possibility of infection even among the vaccinated has led to misinformed claims in some corners that the vaccines don’t really work, or that if they did, boosters wouldn’t be necessary.

As the virus improves its fitness, so do the efforts to undermine vaccination. The goal of getting hospitalization and mortality rates under control is up against mutations not only of the virus itself (the lambda strain, for example, is one of several emerging “variants of interest”), but also mutations in the narrative surrounding the virus. In the rhetorical struggle against the pandemic, biological mutations have the power to destabilize epistemological certainty about what will work against the disease and what won’t. Biomedical narratives respond to such uncertainty by testing new theories and therapies. They evolve as the virus evolves. Conspiracy-based narratives interpret this as evidence that the scientific narrative is fundamentally untrustworthy precisely because it changes. Paradoxically, these counternarratives (if they can be called that) don’t seem to hold themselves to the same expectations for consistency. Instead, conspiracy theorists—believing themselves to have dismantled the narrative authority of science—get lost in endless, unsupported, and self-sealing interpretations. In other words, they seek to overwrite the terms of discourse at will and without regard for evidence.

In this sense, the struggle against the pandemic can be understood as a struggle for narrative authority—a struggle over who has the power to interpret the world of bioculture and how that power is wielded. Sontag was famously “against interpretation” (in her essay by the same name) when it came to art. More precisely, she was opposed to the kind of interpretation that alienates readers from the potency of a work of art by excavating it as a kind of artifact and thereby destroying what was meaningful in it. I imagine some contemporary scientists aligning themselves with Sontag in this respect, wishing that their work be treated in what she called the “old style of interpretation [that] was insistent, but respectful”—a mode that erected meaning on top of hard-earned meaning, rather than tearing it down with hollow zeal. A scientist might even think of her own work as having value that can’t be measured, strictly speaking, but which, like art in Aristotle’s conception, transcends the quantitative in pursuit of the therapeutic. This quest for catharsis—from the Greek kathairein, meaning “to purge”—becomes quite literal when her research is about vaccines during a pandemic. Yet, the would-be interpreters swarm and, with no apparent commitment to hypothesis-testing, manage to get traction with a surprisingly large number of people. How could a rigorously designed double-blinded, randomized, controlled scientific study ever lose the narrative battle against some random guy on Twitter?

One reason, I think, is that it is very difficult for modern scientists to do what Sontag recommends to artists who would like to “elude the interpreters”—that is, to make “works of art whose surface is so unified and clean, whose momentum is so rapid, whose address is so direct that the work can be…just what it is.” In almost every respect, scientific research for the layperson is the opposite: layered and complex, indirect and impenetrable. Where science would sometimes seem to have the advantage is in its ability to produce change rapidly (see the astounding decrease in COVID-19 mortality among the vaccinated). But many vaccine-hesitant people cite the very speed of scientific advancement as the cause of their skepticism. On the other hand, the narrative of the interpreter—here, the anti-vaxxer or the online troll—isn’t encumbered by the pesky challenges of explaining molecular structures or measuring antibody titer levels, but can instead offer faux-therapeutic access to seemingly direct and sensuous experience, the kind of experience that Sontag equates with real art. To those who buy into this stubborn denialism (which often appeals not only to our anxieties and fears, but also the individual and national myths we tell ourselves), it is the scientific narrative that becomes an alienating interpretation, the locus of control and conformity to be resisted. It’s the aesthetic experience of escaping this interpretative lens—of putting oneself beyond the reach of analysis—that I suspect some find satisfying.

Scientific literacy would blunt the appeal of these kinds of counter-narratives, but it wouldn’t be enough. For many people, holding false beliefs about the COVID-19 vaccine will likely need to become costly before meaningful change can happen. Accordingly, in the US and other countries, governments and private businesses have started to experiment with ways to incentivize vaccination, including restricting access to public spaces, vaccine-conditional employment and travel, and direct cash payments for vaccination. Each of these approaches carries ethical risks weighed against risks posed by the pandemic itself.

Without a persuasive, universally shared vocabulary, it isn’t surprising that consensus is so hard to come by. One of the challenges we in the United States face as an epistemologically fractured country seems to be finding the metaphors—there can be no single one—that people recognize as enough a part of their own story to adopt and, in adopting, use to rewrite the history of how we respond going forward. In this moment of confluence between disease, public health, and politics, metaphor might be our best bridge to action. And if metaphor aims to embody truth, the measure of its worth may be taken in the lives it saves.