Near the end of the hellish first year of the coronavirus pandemic, I was possessed by the desire to eliminate sugar—all refined sugar—from my diet. In retrospect, it probably wasn’t the best time to add a new challenge to the mix of mayhem that already seemed to rule my life. My wife and I had been struggling since spring with three young kids remote-schooling and no childcare. My elderly parents lived out of state and seemed to need a surprising number of reminders that there were no pandemic restriction carve outs for Diwali parties and new Bollywood movie releases. Like many people in those early days, we were looking around for masks and trying to make sense of shifting CDC guidelines about when to wear them. In addition, I was seeing patients in clinic at a time dominated by medical uncertainty, when personal protective equipment was scarce, and my hospital, facing staff shortages, was providing training videos and “how-to” tip sheets to specialists like me who hadn’t practiced in an emergency room for years, in case we were needed as backup. It would have been enough to focus on avoiding the virus and managing all this without putting more on my plate. But cutting processed sugar seemed like an opportunity to reassert some measure of order to the daily scrum, or at least to the body that entered the fray each day.

Near the end of the hellish first year of the coronavirus pandemic, I was possessed by the desire to eliminate sugar—all refined sugar—from my diet. In retrospect, it probably wasn’t the best time to add a new challenge to the mix of mayhem that already seemed to rule my life. My wife and I had been struggling since spring with three young kids remote-schooling and no childcare. My elderly parents lived out of state and seemed to need a surprising number of reminders that there were no pandemic restriction carve outs for Diwali parties and new Bollywood movie releases. Like many people in those early days, we were looking around for masks and trying to make sense of shifting CDC guidelines about when to wear them. In addition, I was seeing patients in clinic at a time dominated by medical uncertainty, when personal protective equipment was scarce, and my hospital, facing staff shortages, was providing training videos and “how-to” tip sheets to specialists like me who hadn’t practiced in an emergency room for years, in case we were needed as backup. It would have been enough to focus on avoiding the virus and managing all this without putting more on my plate. But cutting processed sugar seemed like an opportunity to reassert some measure of order to the daily scrum, or at least to the body that entered the fray each day.

That body was beginning—after the years of sleep deprivation that come with medical training and being a parent—to show signs of wear. My former physique was behind me and the stresses of clinical practice during the pandemic seemed determined to speed my transition from dad bod to doc bod. Maybe it was all the pandemic death in the air, but I started feeling like I was what the narrator in Arundhati Roy’s novel The God of Small Things calls “Not old. Not young. But a viable die-able age.” Maybe doing away with sugar could slow things down? More tantalizingly, maybe it could even take me back to a fresher time, the days in college when I had actually gone sugar-free for a while? My friends offered condolences on what they called my soon-to-be joyless lifestyle. But I was set, compelled by literature about the deleterious, even toxin-like effects of added sugar. I had my doubts about being able to pull something like this off again, though, so I decided—as doctors often do—to tackle the problem by studying it. Literally.

That year, in what was arguably a feat of masochism, I began the coursework required to sit for a medical-board exam on dietetics, metabolism, and appetite. By earning another board certification, I thought, I would credential my way to realizing my goal. After shifts at work, during breaks, or once the kids were asleep, I would attend virtual lectures and pore over board-review books in a quest to understand the body’s metabolism. I immersed myself in the physiology of exercise, the thermodynamics of nutrition, and the neuroendocrine regulation of appetite. But this knowledge didn’t break my pandemic eating habits. Cupcakes and ice cream and cookies didn’t call to me any less. And big food corporations were winning the bet that Lay’s potato chips first made back in the 1960s with its “Betcha Can’t Just Eat One” ad campaign. So, I found myself reaching for Double Stuf Oreos while flipping through my medicine textbooks and scarfing chocolate bars even as I correctly answered my practice-exam questions.

My body refused to be disciplined by my intellectual mastery of its operations. I passed the board examination. But my appetite for sugar didn’t change. My official diploma sat in a folder somewhere in my house and I was left with more questions than I had when I started. Was sugar really a problem? Or had I internalized hang-ups about desire from the culture at large? Why did my soul feel so inexplicably sick—so unsatisfied—with the outcome of my first effort to quit that I tried it all again? And what does my “success”—I’ve been sugar-free for a year now—even mean?

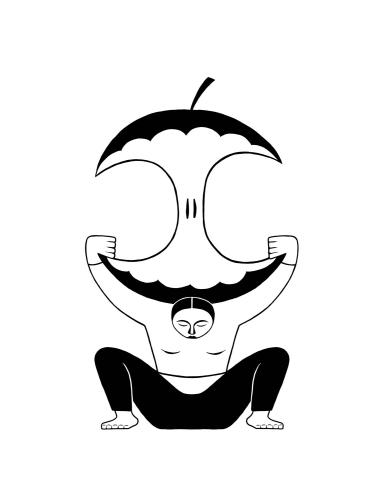

I turned to Plato—a man occupied by appetite—for some answers. In his body map of the soul, the stomach was the dwelling place of desire. Reason, of course, resided in the head, while courage rested in the chest. In this tripartite architecture, it was up to reason—with the help of courage—to subjugate appetite and elevate the individual. Beat back the body, better the being. The thinking went that if we could just rule our stomachs, we might be able to hold our heads up high and our chests out wide. For the Greeks, the right moral posture was key to the good life, or eudaimonia.

Early medical science in the West borrowed heavily from Plato, beginning with Aristotle, who practiced and taught medicine throughout his life. Aristotle agreed that eudaimonia could be realized by moderating the visceral and sensual appetites. He saw the heart as the vessel of intelligence, and arguably the most virtuous of organs. In his hypothesis, the heart occupied—physically and figuratively—a central place in the body, controlling other organs. The brain and lungs played supporting roles, merely cooling and cushioning the heart. Based on animal and possibly human fetal dissections, he described the heart incorrectly as a three-chambered organ. But no matter the number of chambers, the heart was for Aristotle where reason flowed.

Five hundred years later, the Greek anatomist and surgeon Galen challenged the centrality of the heart but still adhered closely to Plato’s triadic notion of the soul. Galen’s treatises, foundational to the development of modern medicine, are suffused with Platonic assumptions, and he painstakingly tried to stitch the divided parts of the soul—the rational, the spirited, and the appetitive—onto specific organs in the human body. In a striking display of topographical certitude, Galen writes in his On the Doctrines of Hippocrates and Plato: “I do claim to have proofs that the forms of the soul are more than one, that they are located in three different places…and further that one of these parts [rational] is situated in the brain, one [spirited] in the heart, and one [appetitive] in the liver. These facts can be demonstrated scientifically.” The Harvard classicist Mark Schiefsky writes that, in Galenic physiology, equilibrium is understood “as a balance of strength between the three parts; the best state is when reason is in charge, the spirited part is strong and obedient, and the appetitive part is weak.”

Should we be skeptical of this aspiration to tame appetite? Sigmund Freud, for one, famously doubted whether desire could ever be so readily controlled. In tossing Plato’s map aside, Freud erased the “soul” and instead sketched a three-part atlas of the “self” and its ratio of desires and repressions—endlessly fractured, negotiating between order (superego), consciousness (ego), and appetite (id). For Freud, appetites could not be overcome but only better managed. Perfect harmony and permanent equilibrium were nowhere in sight. Rather, in Freud’s idea of the self, anxiety for order loomed above the ego, with desire buried beneath it. Appetite was the subterranean tether which consciousness could never escape but only sublimate.

There was something distinctly talismanic about my focus on sugar. So often, liberty is conceived of as the ability to say yes to things. To make affirmative choices: to open this door or that window. But there is also a flip side to that freedom: the power to say no. To refuse. Increasingly during the pandemic, I felt like I was powerless in the face of my cravings. If there was a knock at the door of appetite, a tap on the window of impulse, I had to answer it. And this felt shameful. Why couldn’t I say no? And why was realizing this so painful?

I don’t pretend at anything approaching total understanding of my motivations. But there were a few loosely detected currents worth illuminating here. For one thing, not being able to say no to sugar sometimes felt like a form of bondage to the visceral demands of the body, the very body that I was eager to assert power over, particularly during a global health crisis that was damaging bodies everywhere with disease. If I couldn’t control this plague, could I not at the very least control myself? I wonder now if this insistence on regulating appetite was my sublimated response to the coronavirus’s immense death toll—a way of denying mortality in the midst of its excess. In this respect, perhaps there was not as much separating me from other kinds of pandemic deniers as I would like to believe. Were we all just coping with the inexorability of our decay—laid painfully bare by COVID-19—in different ways, on different time horizons?

Maybe. But there was something beyond the exigencies of the pandemic on my mind as well. The inability to resist sugar cravings—to break the habit—seemed like a victory of the past over the present. It felt like the triumph of the mere memory of pleasure over real satisfaction in the moment. Saying no to that memory—the neurological underpinning of craving—became important because it felt like the only way to say yes to imagination. “I am free only to the extent that I can disengage myself,” Simone Weil writes in “Science and Perception in Descartes.” Detachment from an indulgence, however small, felt like a way to stop being beholden to an old storehouse of desires (and aversions and beliefs). Developing the ability to refuse to reach for the cookie was also a way to break free from the impulse to reach for patterns of the past, from the compulsion of replicating yesterday at the expense of tomorrow. It’s the trick of habit to convince us that we are reaching forward even as we are stepping back. Or, as the British scholar of asceticism Gavin Flood elegantly summarizes: “The less we are able to refuse, the more automated we become.”

If Freud dismantled the soul, modern medicine mechanized what he left of the self. But where Freud’s psychoanalytic theory allowed for a pinch of poetry, materialist models hold comparatively dry sway today. A look at the biomedical literature on appetite reveals a tortuous mix of neural circuits and endocrine pathways, with hormones like ghrelin, insulin-like peptide 5, peptide YY, glucagon-like peptide, and oxyntomodulin, among many others. What’s clear is that if there was a moral valence to appetite for ancient philosophers and physicians, it’s not readily discernible in the language of contemporary scientific literature. A search of the National Library of Medicine for article titles containing the words “soul” and “appetite” returns zero results.

There are upsides to this development. In the modern era, medicine’s tradition-bound framing of appetite as a moral problem has been demoralizing for patients, who often felt—and still feel—objectified, policed, and discriminated against by institutions that sermonize about it. The stigmatization of appetite remains pervasive in the culture, in and out of medicine. The loss of at least an explicit moral valence in the scientific literature is a welcome shift in a medical culture that nevertheless remains saturated with historical assumptions.

In the two centuries since Freud’s conjectures, appetite has been atomized by medicine into a problem of eating—or more specifically, of fighting the body’s tendency toward “disordered” eating. In the pursuit of better and longer lives, maladies of appetite—of eating too much, too little, or not the right kinds of food—have been studied and treated with varying degrees of success. The empirical study of digestion and appetite in the laboratory moved hunger from the moral arena into a biochemical one. Still, in both experimental physiology and clinical medicine, the ancient impulse to locate the appetite persisted: Was it in the body or in the mind? Lines were drawn—and defended—between diseases of the stomach and diseases of the psyche.

What was at stake in the difference? Beyond researchers’ incentives to claim appetite within the domains of their particular disciplines, pinning down the appetite—claiming it belonged to the gut or the brain—was arguably the first in a series of steps leading to its regulation. Understood this way, medicine’s mission to uncover the mechanisms of appetite—despite the erasure of the soul from scientific databases—cannot escape Plato’s legacy. Whether we’re trying to improve or curtail appetite—to up- or downregulate it—we seem unable to resist the desire to control it.

It would have been different—I wouldn’t have felt the need to go all-or-none with sugar—if I could have simply walked away after a few bites. But increasingly during the pandemic, I wouldn’t stop even after I was full. What started off as pleasure would morph into painful excess. Sure, there’s pleasure in abundance, in overdoing a thing. But I found myself barreling past that threshold.

While studying for the board exam in that first, failed attempt at going sugar-free, I was also using various apps and devices to keep track of my body. I had long used a smart watch to log my steps and workouts. I was also using a calorie-tracking app, studiously punching in numbers for every meal and scheming how much I could eat and still remain under the calorie limit. But all that logging and calculating felt joyless and anxiety-ridden. Sometimes, at a meal, in the middle of tallying up numbers like an accountant, I’d explain to impatient friends and family that “I’m just entering my data.” It was a lot of data.

I grew weary of all the inputting, and so I switched to an app with more of a behavioral focus. This app still had me tracking calories, but also came with recipes, a personal coach, and “psychology-based” courses as part of what the company calls your “journey.” The courses were a welcome shift from the myopic focus of calorie counting, and chatting with a coach added an opportunity to get some clarity about my goals. The (presumably real?) coach would share chipper motivational advice and provide tips to overcome obstacles. I diligently went through the app’s “mini-courses,” answered its behavioral questions, and followed its nudges. There were a few weeks where I was able to go sugar-free, but after a couple of months, the coaching advice seemed more and more generic, the courses too simplistic when I was already spending so much time studying for my upcoming exam. I lost interest and reverted to simply recording calories.

I had passed the boards without much to show for it in terms of changes to my nutritional habits. I needed something different, a way to hold myself accountable and mean it. I stumbled upon another app that described itself as being “on a mission to disrupt diet culture and make our relationship with food, nutrition—and ourselves—healthier for good.” It promised live coaching calls with a certified nutritionist, shared recipes, and even offered to tailor my coaching with a vegetarian dietician. It did not ask you to track calories or enter food items from a database. All it wanted was for you to send pics…of your food. It felt radically different than tapping numbers into a screen: Someone else would see this.

The app’s slogan was 100% accountability and 0% judgment. But, to be clear, it was the judgment that I came for. The simple fact that my nutritionist wouldn’t just know but also actually see what I was eating was the killer feature. I answered a questionnaire about my dietary habits and goals. I made it clear that I wanted to go sugar-free and repeated as much to my nutritionist during an intake call. She didn’t exactly endorse this goal, but rather acknowledged it as something that was important to me and gently marked it as a topic that we would come back to, adding that she hoped that I would get to the point where a more balanced approach would suffice. I told her we’d see. I made a promise to take a photo of every meal, good or bad. She kindly reminded me there are not “good” and “bad” foods, and we were on our way.

It’s been a year since I downloaded the app. Every day since then, I have taken a photo of every morsel of food I’ve eaten, whether it’s a handful of pistachios, a salad, or a veggie burger. In every one of those pics, every day, I have been sugar-free. I’ve eaten more vegetables and greens and fruits than I’ve probably ever eaten in my life. My plates look balanced (I make sure of it). I take care to snap pictures that look nice for my nutritionist. Though she never judges me negatively, I look forward to the raising-hands emoji and approving words she sends if she sees a salad with asparagus and garlic balsamic drizzle and avocado up front. Like an influencer on Instagram, I’ll take another shot if the lighting isn’t quite right or if the framing is off. It’s been satisfying to upload a cache of sugar-free images, all beautifully arranged on the app’s user interface. Even more satisfying has been avoiding feeling like the guy who said he’d go sugar-free only to end up sending in pictures of donuts and cookies. Compared to calorie logs and food diaries, the prospect of someone else seeing actual photos of what I’m eating has made the potential pain of falling short feel more proximate than the pleasure of eating sweets. So I just stopped eating sugar. And it’s still working. Was this all it took?

Perhaps the persistent effort to control appetite, replicated across many cultures and times, reveals just how vigorously it resists that very control. The seemingly endless proliferation of constraints on appetite—from the disciplinary to the pharmacological—underscores its untamable quality.

And yet the training of appetite—both as physiological fact and, more abstractly, as desire—can function as an ascetic practice. In this paradigm, as religion scholars like Flood argue, the negation of desire amplifies the subjectivity of the individual. Depriving the body paradoxically accentuates the conscious subject: Hunger unsatiated allows the pangs of the self to be felt more acutely and renders being more vivid. Or as the New Testament unspools it: “When I am weak, then am I strong.” Rather than marginalizing appetite, then, the regulatory action of philosophy around it throws the power of appetite into clearer relief: revealing how desire denied can work as the gravitational center around which the self is constructed. In other words, appetite unfulfilled creates the conditions for expanding self-awareness. This is seen in the Bhagavad Gita in the figure of the ascetic, one who has renounced the pull of appetite and “attains extinction in the absolute”—in seeming contradiction, gaining infinity through loss.

If philosophy is after theoretical victories, science aims more concretely to hack, or at least short-circuit, a physiological truth. Take, for example, gastric bypass surgery, an operation that cuts the stomach into two parts (leaving one functional thumb-size pouch alongside a larger remnant) and radically reconstructs separate intestinal systems for each segment to restrict the amount of food that can be eaten. By shrinking the stomach to fool the mind into feeling satisfied with less, this surgery builds on growing recognition that the long-embraced brain–gut divide is far more porous than previously thought. Recipients of the surgery generally do well in the short term, with reduced appetite, marked weight loss, better control of diabetes, and improved health markers. But the percentage of patients who “fail” in the long-term after bariatric surgery (i.e., achieve less than half of excess weight loss) is reportedly as high as 35 percent. During that first post-op year, studies suggest that an influx of appetite-reducing intestinal hormones decreases patients’ urge to eat. Crucially, however, there are questions about the duration of those salutary hormonal changes and their effectiveness in controlling appetite as post-surgical days add up. For a significant proportion of patients, even surgically shrinking the stomach—the historical seat of hunger—doesn’t offer complete freedom from the specter of unchecked appetite. This fact is not entirely surprising given what is now known about the multiple neuroendocrine nodes that govern appetite, but it poses a conundrum for medical science: Can appetite, as Freud asked in his own way, ever be fully controlled? And if not, is it a wonder that patients turn back to more personal strategies to pursue the work that prescriptions and sutures leave undone?

I can’t say I fully understand why teaming up with a nutritionist on an app worked so well, so fast. Would sharing pics of my food with friends and family in a group chat or a Facebook page have been as effective? Probably not. The issue seemed to be one of epistemology. My friends and family wouldn’t have been as suitable an audience, since they don’t just know me as I am, but also as I was. That knowledge of what’s bygone necessarily shapes the stories we can tell and believe about one another. But with my nutritionist reviewing pictures of my meals from god knows what time zone, the app created an epistemological gap into which both of us could step. It was within this gap that my future self—the self I aspired to be, still unrealized and therefore unknown—could intercede on the present with slightly less inertia from the past. The app provided an illusion that daily life could not, offering a space for the dormant commitments of the future to come to fruition in the present. A space for imagination to overcome memory.

As my sugar-free streak extended, I began to wonder about the future of this illusion. Was it a rare example of tech living up to its glitteringly naïve promise of liberation that wasn’t also entirely dystopian? Or was this an instance of the digital panopticon yet again determining our ability to imagine ourselves, revealing just how far-reaching its gaze is? And, more practically, I began thinking about how long I needed to keep eating this way. The cravings that had once knocked so loudly at my door at the start of the pandemic now softly shuffled from leg to leg right outside it. I could still hear their shoes creaking at the threshold, but they couldn’t force their way in anymore. Things seemed quiet, maybe a little too quiet.

The contemporary quest to control appetite persists for reasons altogether different than those that captivated Aristotle and company. Whereas the Greeks sought to regulate appetite in pursuit of the good life, perhaps what is sought after today is a facsimile of it: a corporatized eudaimonia-lite, where the goal isn’t virtue but efficiency; not equanimity, but productivity. In this view, it’s not a better way to live we’re seeking, just a less painful way to work and die—all while “looking good.” A more charitable and poetic possibility is that the constraint of appetite continues to appeal because it provides the same sense of structure to selfhood that metre does to a poem: a limit against which to construct narrative unity of the psyche.

As fascinating as it is to think about this question, even more essential ones—about the links between appetite, scarcity, and loss—loom in the writings of Toni Morrison, an artist who provides a necessary counterbalance to the ironic obsession with appetite restriction in societies that are glutted with luxury. In particular, I’m thinking of Beloved, which, as is well-known, tells the story of human beings struggling for survival and wholeness in the face of slavery’s horrors. But what’s also received some scholarly attention is how, in portraying this struggle, Morrison uses the language of food and appetite to unfurl narratives that are saturated with the metaphysics of hunger: the difficulty of sating the self; the confusion between hunger, history, and hurt. I was struck by this unexpected resonance while rereading the book in the middle of my bid to quit sugar. Morrison’s metaphorical stance toward appetite felt distinctly more ambivalent than that of so many thinkers who precede her. Her characters are people who think about what it would mean to satisfy what the narrator calls their “original hunger”—and whether doing so is even possible. They imagine getting to a place “beyond appetite” but are also compelled by history to contemplate the price of doing so.

In my improvisational reading of this inexhaustible text, the denial of hunger risks becoming a costly exercise in self-abnegation—a severing of self from history, of self from self—whose consequences Plato doesn’t seem to fully consider, but which Morrison is deeply wary of. I think Morrison is, like Freud, skeptical of the metaphysicians who would have us render hunger subordinate. But where Freud is an anti-idealist, Morrison appears willing to reach for hunger, perilous though it may be. Straddling both the risk of self-destruction posed by contact with the original hunger, and the anguish of self-denial created by leaving it unrecognized, Morrison casts her faith in the human—perhaps über-human—ability to embrace the beautiful, blood-hued predicament of incarnation.

About ten months into my sugar-free life, a scent from the pantry hit me like it hadn’t for a while. My wife had just baked chocolate-chip cookies for our kids as a treat. By then, I was unphased by sweets around the house. They might as well have been made of stone. But, at the end of a long day, I found myself unexpectedly at the pantry door. Minutes passed. After a while, I opened the Tupperware container and inhaled. My mouth began to water. I could almost taste the cookies. I remembered the delightful way the chocolate melted at the back of the tongue. I remembered the satisfaction of soaking a warm cookie in milk. A part of my brain was humming, eager to replicate the memory of sugar, butter, and dough on the cortex. Another part was already dreading the pain of not being able to stop. I picked up the cookie and, having built nearly a year’s worth of muscle memory, simultaneously opened the app on my phone. I centered the confection in the glowing frame and was about to press send when, looking at the screen, it hit me: What would my nutritionist think?

As of this writing, my streak remains unbroken, despite a few close calls. In many ways the story seems to be going the way I intended: I am eating well-balanced, sugar-free meals and haven’t counted a calorie in more than a year. The cravings that were troubling me aren’t gone, but the future version of me—the unsweetened aspirant—grows asymptotically closer to the present with each picture I snap. I feel the spiritual and physical acuity—the intensity of my own subjectivity—that comes with ascetic practice. But I also feel some qualms about neglecting Morrison’s original hunger, with all its attendant risks and possibilities. I think about the sacrifice I’ve made of memory at the altar of imagination, recognizing the chance I am taking by placing that bet if imagination ends up being overrated and memory proves to be the last storehouse of joy. But then I remind myself that visions like Morrison’s are often too large, too untimely for us to inhabit. They come from a place we haven’t arrived at. At least not yet.