When I was young, my dad would take me to the hospital, usually on weekends, mostly on Saturdays. He was visiting his patients, the ones he’d operated on earlier that week, when he’d replaced their hip or their knee. I remember these mornings quite well because I knew, even then, that they were not normal. I knew, I suppose, that I was in a space where most children were not. Certainly not healthy children, wandering the halls, marching into and out of various rooms on a Saturday morning, when I could have been watching cartoons. It was thrilling: the bad food, the weird smells, the old people stuck with tubes, their papery skin, the smiling nurses, the gleaming-white walls and squelchy speckled floors, and my dad, in lab coat, delivering quick comfort to people—in charge, certain. I suppose this is my way of explaining why it was, not so long ago, with a day’s work done and an afternoon free, I found myself wandering into the Royal College of Surgeons, in London, among thousands of specimens—bones and organs of beast and man—before standing and gazing at a large glass case filled with jars of floating ovaries.

They were gray and beige and white in parts. Some smooth sections caught the light and shone like alabaster. Many of the ovaries had come out of cows. Several had come out of dead women. Some—the cows’—were the size of hubcaps. Others were oblong, like footballs. A half dozen of the jars had labels, a string of numbers, an identifying mark. Most did not. To find out where some of the ovaries came from, I had to look down at a key below the display, and even then, all that was listed was the type of animal, nothing about where it came from, whose ovaries these had been, how they had been removed, or how they came to be preserved in a jar, displayed in a glass case more than two centuries later.

The jars were a small part of a huge collection created and overseen by an eighteenth-century surgeon named John Hunter. This was his museum: the Hunterian. Hunter had started out a cabinet maker, then taken up medicine at the age of twenty after visiting his older brother William in London. William was teaching anatomy and working as a physician, specializing in obstetrics, and his younger brother assisted him with dissections. After a few years, the younger Hunter took a job as a surgeon in the army, and after a few more years he returned to London, where he began working with a dentist because the money was better. Hunter had the idea that a tooth might be transplanted from one customer to another, which he attempted. It did not work. The tooth did not take—it rotted away. Hunter pressed on, dreaming of swapping not merely teeth but entire organs.

His idea was to take out what was sick and either replace it with something not sick or get rid of the sick thing entirely—and if the thing itself seemed extraneous, replace it with nothing. There was evidence of his ideas all over his museum, not just in the removed organs but teeth transplanted in odd places, like a cock’s comb, where they’d managed to take root. But looking around at all the jars full of organs, it appeared that Hunter was far more adept at removal than transplantation. Sometimes the sickness Hunter seemed determined to cure was childbearing itself. Hunter wrote that, in the case of malignant cysts, an “ovary might be taken out, as they generally render life disagreeable for a year or two and kill in the end. There is no reason why women should not bear spaying as well as other animals.” Hunter removed many ovaries from many dead women (mostly while helping his brother William write a book, The Anatomy of the Human Gravid Uterus Exhibited in Figures) but it’s also been speculated that he attempted ovary removal on some while they were still alive. Surgeons long dealt with death, not just regularly on the operating table, but in their research. They needed bodies to study. Hunter was a known grave robber. Eighteenth-century Londoners coined a grim phrase for these body snatchers. They were known as resurrectionists.

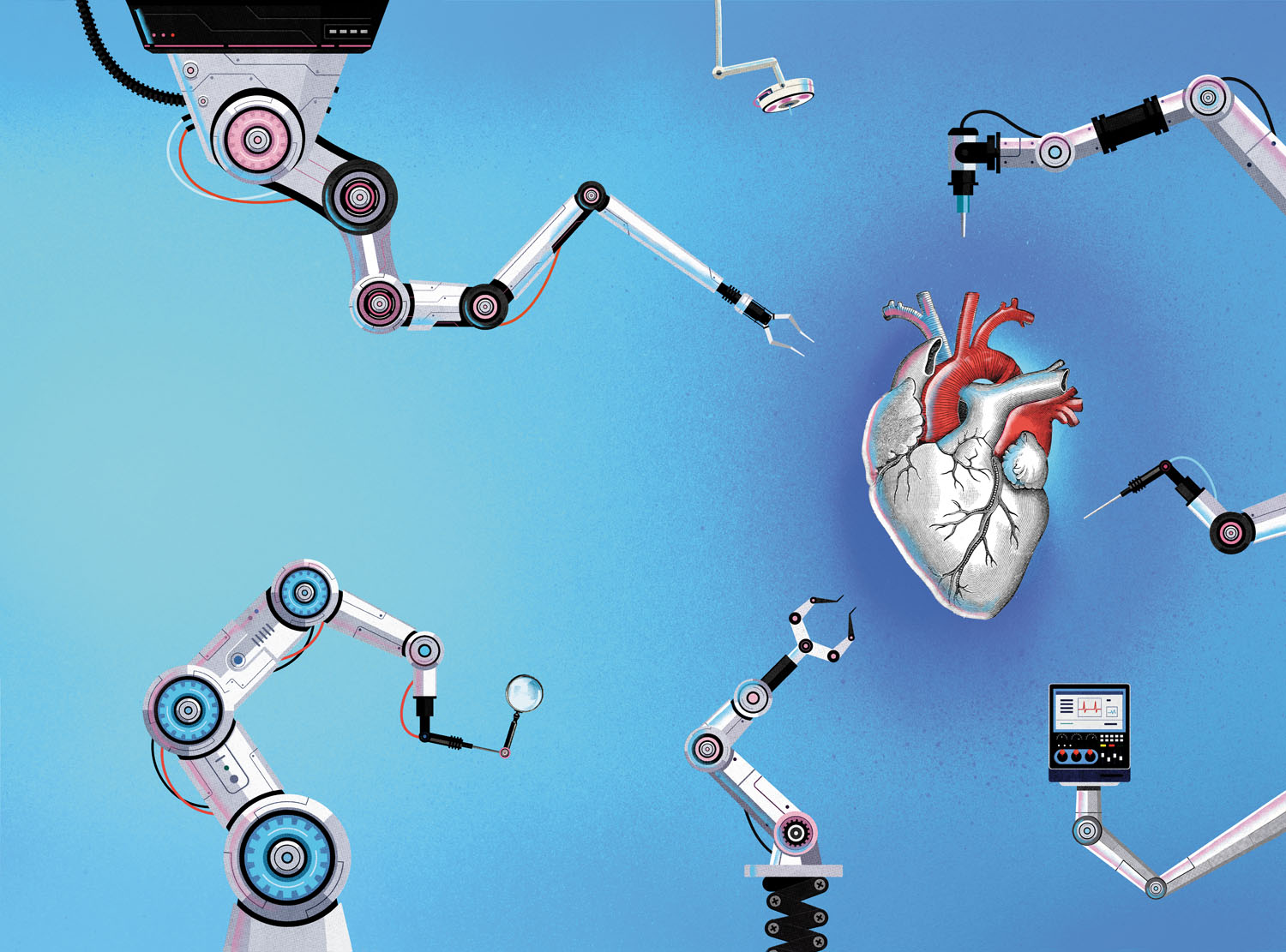

I once received an invitation from a heart surgeon in Seattle to watch him perform surgery using a robot. “A robot-assisted performance,” is how he described it. A few months passed before the surgeon put me in touch with a patient named Frank, who gave me permission to be there in the operating room during his double bypass. By then it was October. When I arrived at the hospital the morning of Frank’s surgery, it was still dark, predawn, the rain coming down so slanted that when I passed through the sliding doors into the silence of the hospital foyer, I noticed that one of my pant legs was soaked through while the other was still dry.

A bored-looking security guard sat at the front desk. I gave him my name as well as the name of the surgeon I was supposed to meet. A television mounted to the wall behind the desk showed more sideways rain, plus scenes of angry surf, bending trees, and swamped cars on flooded roads—not the same storm as outside, but a hurricane bearing down upon the East Coast. I made my way to the restroom and tried to dry my pant leg with too many paper towels. By the time I’d returned, the surgeon was standing by the front desk, staring into his phone. “Ah,” he said, looking up. “Yes. Good. Let’s go.” He told me that he had to meet with the patient—Frank—one more time before the surgery. But first, he said, he’d get me settled in.

We walked down the hall, turned a few corners, the floors squeaky clean, our footsteps clacking, then squelching, breaking the low hum of institutional silence. We passed a set of doors and entered a room that at first looked like a command center and then took on aspects of a break room. One wall featured a long window that looked out into the operating room. On a table in a corner of the room stood a coffee maker and beside it, two surgical assistants—nurses—were softly talking as one poured herself a cup. The rest of the room was filled with row after row of long tables and, lining each, a bank of computer screens. The surgeon stopped next to a section of the table, beside a window overlooking the operating room. “Why don’t you set up here,” he said. He looked at his phone again, glanced at his surgical assistants, turned, and exited.

I sat and pulled out my notebook and digital recorder, arranging them on the desk in front of me as a quiet kind of announcement of my presence. Near the two nurses, mounted up by the ceiling, was another television showing similar footage as before: battered seashores, bent trees, swamped roads. A graphic depicted the hurricane’s predicted path up the Eastern Seaboard and, as I traced it, I realized the tip of the arrow looked like it was aimed directly toward where I lived in New York. I pulled out my phone, thinking I’d try to call or send a text to someone back home, but there was no reception, and I had no idea what I would say. I stared at the muted television a minute longer, until I caught a particular phrase from one of the nurses, the younger one. Something about handling dead bodies, the smell.

She was telling her coworker about her childhood. Her father had run a mortuary, she said. That was why she had encountered the dead at an early age, why she had always been comfortable around bodies. It was the smell, she said, that was for her a strange kind of comfort, the thing most locked in her memory of that time and place. Not the smell of the dead, but the smell she associated with a corpse, the smell of formaldehyde and disinfectant and the clean spare room where her father went to work and where she, when she visited, received a Dum Dums lollipop. It was strange, she went on: gross, macabre, whatever, but she had a fondness for the smell; it was kind of sweet and clean, the comforting secret between her and her father. Sure, her brothers shared this secret, but they didn’t like it the way she did. And her mother rarely spent any time in that room with the bodies. She was better with the living. Front-of-the-house stuff, the nurse said. The work was hard, the hours terrible. She guessed that the attraction had been getting to see her father in the place where he spent his days away from home, seeing where he went when he wasn’t her father.

“There were five of us,” she continued. “All brothers, then me in the middle. We’d get to take turns getting dropped off there after school, a kind of reward—good grades or a gold star or, you know. Some kind of pat on the back. That was probably the beginning of…” She looked past the coffee maker and over to the wall where I sat, over to the window that looked out into the operating room. “All this.” She continued: “I liked the tools. They were all so, specific?” The older nurse nodded slowly, listening. The younger nurse said she remembered one day after school particularly vividly, after she had been dropped off to be with her father. She got there, and he was clearly not himself. “Upset,” she said. “Or something. Troubled.” It took her a while to realize his mood had nothing to do with her except, maybe, for her being left there to be with him. Something was wrong in the room where he worked, the room with the bodies. Or, not wrong, maybe. That was the thing—she didn’t know because it was the one day she wasn’t allowed in there. Or maybe there were other days she couldn’t remember, but she remembered that day. He planted her down in the reception area and asked her if she could do him a favor and be as good and quiet as possible and not leave this room, and definitely not come near the room where he would be working. And he left her there, staring at the carpet, wondering what was different about the room where he worked that day.

It consumed her, this curiosity. So much so that it became like an ache, and of course she very quietly left the room she wasn’t supposed to leave and went to the door that led to the room where he was at work, and put her ear up to it and heard—not a thing. “Not a dang thing, not for a long, long while. I remember just waiting and waiting and this lump in my chest that was nerves or what I don’t know, just growing until I could hardly breathe. Then a quiet little tap-tap-tap sound from far away, inside. Maybe it was water dripping, maybe it was my dad, reconfiguring someone’s face, I don’t know. I’ll never know. I got away from that door quiet as I could and went back in the room, sat on the carpet, and tried to think about something else but couldn’t. Couldn’t for weeks.” She exhaled, then added, “They sold the place a few years ago. Asked me to take it over after offering it to all my brothers first but, no, there’s no money in it. And besides, I wanted out. Out of Texas, mostly. But out of that business too.”

Jane Crawford’s ovaries aren’t on display at the Hunterian, or anywhere else, but Jane Crawford was the first to survive having them cut out. The man who removed her ovaries was named Ephraim McDowell. He is not mentioned in the Hunterian either, though he’d studied surgery in Edinburgh, under the Scottish anatomist and surgeon John Bell. Both he and Crawford lived on the Kentucky frontier in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

Jane Crawford had a family: three boys, one girl, and a husband, Thomas. The Crawfords lived in Green County, in a cabin on the Blue Spring branch of the waters of Caney Fork. Danville, among the largest settlements in the state, was a two-day horse ride away. Three days if the weather was bad. In the fall of 1809, Crawford began complaining of an ache in her stomach. For several weeks and all through an early-season snow, she had staggered about the house in wretched pain. A lump was forming, she could feel it. Her stomach began to swell. She saw two doctors, and both believed she was pregnant with twins—and so late in life (she was forty-four years old). When she didn’t deliver at the expected time, it’s likely that one of these frontier physicians called for McDowell, who lived in Danville, for he was the best-known physician in the state.

It’s unknown just how much time passed before McDowell arrived, though some time certainly did. The landscape throughout most of Kentucky remained wooded and wild, speckled with small clearings for farms, cut through with narrow paths just wide enough for a horse cart. The journey to Green County was, if not uncommon, not easy. McDowell might have hesitated to undertake an arduous house call for such a minor case. And time, back then, was a different companion than it is now, living as we do in a constant awareness of the often-dreadful urgency of its passing.

When McDowell arrived at the Crawford cabin and began his routine examination, he found, after prodding the mass in her belly, that it was not twins, not a pregnancy at all, but an ovarian tumor. McDowell knew the mass could soon grow large enough that she would no longer be able to move. Soon after that, the growth would kill her. Treatment was impossible. Or, if not impossible, it had never been done before. Yes, abdomens had been cut open, tumors had been removed, but no patient had survived. He explained this grim fact. After a long and prayerful silence, Crawford replied that she would prefer a sudden death caused by an unsuccessful surgery to the drawn-out agony she’d face if nothing was done. Years later, when he put down his recollections of the case, McDowell wrote: “I told the lady I could do her no good. That opening the abdomen to extract the tumor was inevitable death. But not standing with this, if she thought herself prepared to die, I would take the lump from her.” She appeared, he concluded “willing to undergo an experiment.” But there was a catch. She would have to travel back to McDowell’s home in Danville. It was the only place, he told her, in which he would be willing to attempt such a risky operation.

Crawford made the journey tied to her horse, cocooned in blankets, her bulging, cancerous belly resting on the pommel of her saddle. The trip took three days. Beyond that, the specifics weren’t recorded. We don’t know where she rested or what she ate. We don’t know anything about the pain, whether it was so great that it spurred her onward or slowed her down. In some accounts, there is an aside about Jane Crawford’s fortitude, her frontierswoman spirit, her bravery in the face of death, and how it represents, in its small yet epic way, the stoicism of all the European settlers carving a civilization out from the wilderness. In these same accounts, the more basic truth—that she was alive and suffering and facing a miserable and certain death—escapes mention. The ride, the choice: a chance at a different fate.

Once in Danville, McDowell prepared for surgery. He would be assisted by his nephew, James, and his apprentice, Charles McKinney. On Christmas morning, the three men moved a heavy oak table from the dining room into the rear annex built for McDowell’s medical practice. The room was spare but well-lit and kept warm by a fire raging in the next room of the main house. The three men put the table in the middle of the room, then draped a sheet on it before tying ropes to its legs. To the ropes’ other ends the men tied Jane Crawford. Some accounts have it that they placed a few drops of laudanum onto her tongue. Others claim they gave her a cheery bounce: a whisky, cherry, and spice concoction. Most don’t mention a ministration, and it’s likely she wasn’t given anything at all. What is certain is that, before he began, McDowell wrote out a prayer, seeking guidance and a steadying hand: “Direct me, Oh! God, in performing this operation,” he wrote, “for I am but an instrument in Thy hands, and am but Thy servant, and if it is Thy will, Oh! Spare this poor afflicted woman.”

He put the prayer in his pocket, then asked his assistants to tighten the ropes and pin Crawford to the table. He removed his coat and, knife in hand, he approached her swollen belly. He cut through Crawford’s abdominal wall and her peritoneum—the membrane surrounding the ovary—and into the twenty-two-pound tumor growing out of it. His initial incision was nine inches long. When he reached the tumor, he cut into it too, but first he tied a small length of twine around Jane’s fallopian tubes to minimize the bleeding and any contamination that might come from the tumor. He described the cancerous growth as “fimbrious” and “very much enlarged.” He also noted that he had never seen such a large tumor “extracted…nor heard of an attempt or success attending any operation, such as that required.” Draining the abdominal abscess surrounding it took several minutes. McDowell then cut out the growth, as well as the ovaries and fallopian tubes, sewed up his initial cut, and cleaned the wound. Twenty-five minutes had passed.

Many reports of the surgery describe a crowd of near-riotous townspeople gathered outside McDowell’s house, a rope at the ready to hang the doctor for murdering a pregnant woman. The crowd was said to have disbanded once a sheriff entered the home and confirmed that the procedure had been a success, and that Crawford was still alive. But there was almost certainly no crowd, no hanging rope, no sheriff checking the patient’s pulse: All mentions of the mob came decades after the event itself. The only reliable account is McDowell’s. From the surgeon we learn that five days after surgery Crawford was making her bed and tidying the room where she’d been convalescing. After a few weeks, she rode her horse home, unescorted. She lived thirty-two more years, to the age of seventy-eight.

Soon after the young nurse had finished her story about her mortician father, the surgeon came back in to tell me they’d be bringing the patient into the operating room very soon, and while he was still conscious. Frank had specifically requested to see the robot. Parts of the machine would soon be beneath Frank’s ribcage, gently tunneling toward his heart, rearranging some of his clogged arteries by slicing, knotting, and bypassing two of them. Through the window into the operating room I could see, off to the side, the robot that would be used for the surgery: a hulking instrument draped in plastic, all bulky and beige. I watched through the glass as one of the nurses, her face and head covered by a white mask and thin blue cap, opened a door to the operating room, walked over to the robot, and began extending its three jointed arms. It was careful, tender-looking work. For a moment, while she gazed up at it, the nurse and the machine looked a little like a pair of middle-school dancers, the robot the awkward victim of an early growth spurt. She moved her partner closer to the operating table, pushing and pulling its body and arms before retreating to one corner. I tried, then, to imagine the patient lying on the table, under the robot, but somehow found that difficult to do. The big machine seemed to take up more space than would allow for a human underneath.

I walked back to the desk where I’d been seated and watched more of the techs’ work: arranging instruments, adjusting tables, checking that everything was in place. Another assistant, one I hadn’t seen until now, entered the room backward, carefully wheeling in a bed. Laid out on the bed was Frank. His thinning white hair was rumpled, his round face drawn. He had bags under his eyes. He looked tired and disheveled, which didn’t seem a fair observation to make. Unlike everyone else, Frank was naked, and the sheet that covered him was beginning to fall off. As he moved from his gurney to the operating table, Frank gazed at the robot.

He told me later that, as excited as he’d been to see it, his memory of this moment wasn’t too clear. There was a lot going on, he said. But, he asked me, was the robot draped in something? Covered, or something like that? Yes, I said—there were thin plastic sheets on parts of the arms. “I wonder what those were for?” Frank said. I told him I thought they were there to keep the machine clean. “From what?” From your blood, I ventured. There was a long pause and Frank said, “Oh,” and, a moment later, “That makes sense, I suppose.” What he did remember was that the room was very bright, and the robot did not look quite like he’d imagined. What had he imagined? Frank said he wasn’t sure. He also remembered that, just before he went under, there was the feeling of the needle breaking his skin, followed by a hot and frightening rush throughout his body that subsided, like a slacking tide, into a warmth, weighing him down before he went out.

The action inside the room slowed down while Frank drifted off. The assistant who’d wheeled him in stood beside him, making sure he was under. Once he was, the action sped up. Frank, in a deep, drug-induced slumber, seemed to no longer be Frank but, instead, had turned into “the patient.” One of the techs began shaving the patient’s chest as another began moving a tube down the patient’s throat. A third started painting the freshly shaved skin with a layer of iodine-tinted disinfectant. The patient was abstracted, now nothing more than a body, and even then, not a whole body but parts, especially the chest, which began to swell as it filled with air, the respiratory system locked in a perpetual and unnaturally deep breath caused by the tube down the patient’s throat. I could see, from across the room and through the window, small bubbles forming from the excess gas in small patches under the yellowed skin. The body then disappeared almost entirely beneath a blue smock. All that remained was a window surrounded by the draped blue smock, a rectangular section of eerily swollen skin, glistening amber under the bright operating-room lights. It was like a picture, or a portal, framed in blue. The full fact of Frank was gone. And suddenly, so was the rest of him: One of the techs pulled a curtain across the window, cutting off my view. I sat back down, looking at the clock. It was just past nine.

Imagine all of what’s inside us as gears of a clock—that’s how Descartes put it. What ails us might be fixed. The great insight was to consider bodies as vessels, filled with parts. Disease did not necessarily mean a breakdown of the entire organism. Disease could be specific, often was specific. A cure could dwell within one part of the whole. A few decades after Descartes put down his theories of the body and disease, a Dutch anatomist named Herman Boerhaave modeled the systems in our bodies as a series of tubes through which pressure and liquid flowed and naturally equalized. Illness wasn’t broken-down gears, nor clockwork—it was plumbing. The natural force that controlled the levels remained a spiritual question (Descartes’s “ghost in the machine”) beyond medicine’s concern. That began to change in the early 1700s. A living organism was machine-like, but it was also something more, because it could do things a machine could not: It could grow and change and rebuild itself. John Hunter began experimenting. He grafted a human tooth to the comb of a rooster, and found that the roots of the teeth began growing, and growing, all the way into the bird’s brain. Toward the end of the century, Luigi Galvani, and later, Alessandro Volta, ran electrical currents through dead frogs, making them hop again as if they were alive. The scientific debate between the two scientists over the possibility of “animal electricity” caused a sensation. By 1818, the idea of a body as a machine, animated by electricity and cobbled together out of component parts, landed in a new kind of novel for a new kind of age when Mary Shelley published Frankenstein; or, the Modern Prometheus.

I was waiting at the desk in the room where I’d been told to wait, the curtain cutting me off from the activity beyond for several minutes. Tired of the silence and with nothing left to look at, I’d pulled a chair over to the wall-mounted TV to adjust its volume. A meteorologist was talking about pressure systems and millibars and how he’d never seen a storm like this one. The anchor seemed uncertain of whether the reported number was especially high or low, and what might be cause for concern, but before I could see how this ended up, the surgeon entered and apologized.

He was sorry about the wait, he said. The room was ready. “Oh,” he added, “you’re not scrubbed up. We need to do that.” He turned and I followed him into a small dressing room with a few lockers and a shelf of folded-up pants and smocks, masks and hats. The surgeon pointed to these and, as I slipped the clothing over what I was wearing and tied the cap and mask, he detailed what I soon would see. There were two arteries he needed to find, then bypass, which meant cutting and removing a bit of the artery that was clogged before sewing it back together. Both arteries were descending: one on the left, just below the heart; the other on the left anterior, on the heart’s outer face. In a moment, they’d be hooking the patient up to the heart–lung machine. We washed our hands and forearms in silence. Before he turned away from me to enter the operating room, the surgeon said, “Follow right with me until I tell you not to.” Inside there was music playing. “Under Pressure.” I followed the surgeon across the room from where we’d entered, over to two consoles the size and shape of video-game cabinets in an arcade, sitting side by side. “I’ll be here, and you’ll be here.” He gestured to one console, then the other. He sat. I sat.

I moved my arms forward, my hands progressing beyond the resting pad for my forearms and elbows, and toward the machine’s clasping controls. “Please,” he said, “don’t touch those.” I apologized and pulled my hands back. I watched the surgeon move back and forth between the patient and machine a few times before, with help from an assistant, he nudged the robot away from the table very slightly. He conferred with the anesthesiologist, seated near the patient’s head, hidden somewhere under the dark-blue sheet. The surgeon bent over the framed patch of yellowed chest. It was time to begin.

Using a red pen, the surgeon drew a series of small dots, then X’s, along either side of the chest, just beneath the rib cage, where his incisions would be. He pocketed the red pen, then moved his arm forward and offered his hand, into which the assistant quickly placed a scalpel. He stared at the yellowed chest, his red marks. A moment passed. The faint whir of the machines, a sigh from the heart–lung box, and a slowed beep-beep-beep from the anesthesiologist’s cardiogram. The surgeon made his first cut, then another, then another: three quick gashes down the left side. He leaned in and made three more down the right. The cuts bloomed open but did not bleed much. The surgeon passed the knife off and was handed a metal tube, which he planted into one of the wounds, twisting it in until it was stable. He planted two more metal tubes into the yellowed chest, sticking out and gleaming under the bright lights.

An attendant wheeled the robot closer to the operating table, taking hold of its arms and extending them over the body while another assistant connected a camera, a cauterizer, and a clasping tool to each. They moved the three arms just above the three metal cylinders, and the surgeon carefully threaded the arms down into the cylinders, right next to where he’d performed his initial cuts. He walked back to the console. “Now,” he said, “let’s get to it.”

He bent forward, slid his hands into the controls, and began moving them, gently at first, then more quickly. The motion reminded me of a conductor’s delicate movements during the softest pianissimo portions of a symphony, or of the devout passing prayer beads through their fingers. There was a sizzle and zap sound, followed by a harsh and sour burnt smell. Another swiping motion, then a sizzle and zap. Again the burn. Slash, sizzle, zap, burn; slash, sizzle, zap, burn. Movement, followed by the sound, then the smell drifting across the room. I realized suddenly that the sound was the cauterizer and the smell was searing flesh. I leaned into the viewfinder, steadying myself as everything went blurry, then snapped into focus.

The view inside the patient’s body was cramped, then cavernous; fleshy, then not. As the surgeon cut a path toward the patient’s heart, he adjusted the robot’s camera and light using a set of pedals at his feet, moving the tiny rig along with the small slashes and cauterizations, under the ribs and onward. Out of the pink and red caverns, a dark, mysterious vista appeared. And beyond it, a ghostly, planetary orb floated in and out of view. I asked the surgeon what it was. “The left lung,” he whispered, then adjusted the camera angle and kept going.

I shifted in my seat, looking back, taking in the room, and as I did so my hand brushed against the controls in front of me. There was a beep from my console, then a beep from the surgeon’s console. He, too, looked back. “Huh,” he said. “That’s odd.” I stood up now, my hands raised in a position that suggested I didn’t know or do anything (even though I suspected I had). “Hmmmm,” the surgeon said, staring into his screen. I sat back down and peered into my screen again. On it, superimposed, was the word error followed by a long string of letters and numbers. The surgeon tapped at his controls but the machine wouldn’t respond.

He stood up, walked back over to the operating table, and spoke to his assistants. I couldn’t make out what he was saying—the conversation was quick and quiet—but he immediately began helping them remove the robot’s instruments from the cylinders planted into the wounds. He then walked over and explained to me that they were going to have to restart the system, meaning restart the robot and everything attached to it.

A few of the techs and assistants briefly left the room. Everyone else sat down. The anesthesiologist checked his watch, the patient’s vitals. More beeps from the consoles, and more movement from over at the table. Soon, we were back up and running, and I was back inside, staring into my screen. An artery emerged out of the thick gloaming darkness beyond the left lung. It looked like a rusty-red tree branch covered in layer upon layer of pink and white jungle vines. Through the viewfinder, the robot’s tools looked enormous, lunging in the foreground, tugging at the vines, the cauterizer swooping down and delicately frying bits of flesh. Tug, swoop, sizzle. Tug, swoop, sizzle. And the branch began to come free from the fleshy tangle.

The surgeon paused now and looked at me. He said that we were about to reach his favorite part: the bypass itself. Here the goal was to graft the patient’s artery back to his heart by stitching it. I watched as he delicately controlled the robot’s tiny claw-hands, passing the hooked needle through the flesh, swooping and pulling the artery back into the heart. The surgeon finished his second set of stitches and was now checking his work by pinching the other artery, still open and unattached, as small drops of blood burbled out. He was concerned, he said. The blood flow wasn’t good enough. “I’m not loving this,” he said. “There should be more blood.” He left the console and walked to the wall by the door through which we’d entered, picked up a phone, and dialed the chief cardiologist to discuss the situation. It was nearly 1 p.m., and almost four hours since the patient had gone under. The surgeon hung up and marched back over to the table. An orderly entered the room through the double doors the patient had come through, pushing a table with more tools. I sat on my stool by the console and watched as the attendant removed the robot and the metal cylinders from the patient. The surgeon and several assistants took up some of the new tools and hunched over the exposed chest. I couldn’t see what was happening, but as I stood, I heard a loud rip, like a sword emboweling a couch cushion. There was a flurry of cross talk, and, when that subsided, the surgeon called me over.

He stood over the patient’s chest, and I stayed behind a plastic partition, beside the anesthesiologist and the patient’s still-hidden head. The chest was split open in the middle, the ribs and skin held back with large metal clamps. The surgeon said he’d told the patient that there was a decent chance this would happen: that he’d be unhappy with the results of his robot stitching and be forced to perform a traditional, manual open-heart surgery. The ripping sound, he explained, was him sawing the patient’s sternum open, then breaking back his ribs so that he could finish the procedure with his hands. There were minutes that had to pass before he could go on, the surgeon said. The body had to be chilled, the heart slowed, so that he’d be able to work on it. The robot was surer and steadier, so the body could be warmer, with the heart beating more visibly, almost violently, as it still beat now. The surgeon left the table for a moment. I lost track of time, staring into the open chest as it lurched, alive. It was all oddly logical, contained, surprisingly clean. So much of the body was still disappeared, under the blue sheet and bright lights. There was a strange feeling of familiarity, of it appearing hyperreal. Particularly as time passed and the breathing lungs slowed, it began, I thought, to look almost fake. Now the twitching and thumping heart merely trembled. Now time sped up. An end was in sight. The surgeon sat; the hand-done stitch held true; it was all to the surgeon’s liking. He stapled the chest back closed. They wheeled the patient out. They began cleaning the room. Someone said I could leave if I wanted. Then someone else said I should leave now that I had the chance. I remember shaking the surgeon’s hand, being led to the door, and walking quite a ways down the hall before realizing I was still in my scrubs.

Around the corner from where I stood in the Hunterian, I heard someone loudly clear his throat. I turned the corner and saw an old man talking to three students. At least, I assumed they were students—they were young looking and nodded dutifully as the older man spoke. They were standing next to the skeleton of a giant. The students scribbled into small black notebooks. “Do you think it matters, that we know his name?” the old man asked.

A sign said these were the bones of a man named Charles Byrne, just twenty-two when he died, a shade over seven feet, seven inches tall. He’d found an uncomfortable fame in the last year of his life, in London, and made a small fortune off his celebrity that must have seemed like true wealth to Byrne, for he was born dirt-poor on a tiny farm in Northern Ireland. In a robbery, he’d lost nearly everything. Soon after—perhaps because of the stolen money, or because of mental-health issues attributable to the enlarged pituitary gland responsible for his gigantism—he grew depressed, turned to drink, took to his bed, and died. In his final days, Byrne worried over what might happen to his body after his spirit departed. He asked that his friends seal him inside a lead coffin and bury him at sea, for he was haunted by the thought that his body would continue the career he’d begun, that he’d remain a spectacle even in death, that his bones would get no rest. Byrne’s fears turned out to be well-founded.

His body was likely stolen from the lead coffin and replaced with dead weight en route to the seashore. Years later, the bones reemerged as part of Hunter’s voluminous collection. The plaque bearing Byrne’s name enumerated a few points about his life and fame. The vagaries of his death and the events immediately following were not mentioned. Nor was John Hunter’s reputation throughout London as a man who was in the market for dead bodies, who would buy them fresh, straight off the gallows or newly in the grave. Hunter paid his resurrection men extra for acquiring a corpse that was deformed or otherwise anatomically curious. He even robbed graves himself. One of his diary entries reads: “Sept 1758. In this Autumn we got a stout Man for the Muscles from St George’s ground.”

One of the students, a young man with wire glasses and jet-black hair streaming down to his shoulders, took up the old man’s question first. Yes, he said. He could see how it was disturbing, to know about the person, to know his name, but at the same time wouldn’t it be wrong to withhold information, especially seeing as this was a museum? These were someone’s bones, better that we know whose they were. The purpose of this place was to educate, he said, and besides, it was a long time ago. The giant had been dead for centuries. He had no kin. Who was left to complain?

Another of the students shifted her weight forward slightly and said she thought it was awful, how his remains had been treated, that they’d been put on display to be gawked at all that time ago. And were things so different today? We were gawking at them now, thrilling at the display of something bizarre and slightly illicit, while forgetting that this particular thing had been—was, in fact—a man. Now there was a changed, more appropriate-seeming context, she said, speaking slowly, thinking out loud. But it did not seem all that different fundamentally than before. We say now that it’s educational. That’s what she’d told herself, too, about this visit. But wasn’t the argument similar then? Hasn’t the essential nature of the display, its basest quality, remained unchanged? It was still like a show, she said, only the people back then were perhaps more honest.

The old man nodded. Yes, yes, he said, “But they show bodies today, still, don’t they? And we don’t know who they are, really, do we?”

The third student made a motion like he was about to say something to this, but then the first spoke again, only to add that he’d seen these more modern displays of plasticized bodies and, yes, the identities were often obscured, but that wasn’t what was off-putting: It was the atmosphere of the crowd. People were surreptitiously taking photos, though photography wasn’t allowed. He’d come upon a group of teenagers, cackling and gesturing toward one of the plasticized body’s groins. A leering father pointed at the muscles around a body’s breast while his son looked on with wonder. It all seemed, the student said, “disrespectful and disgusting, nearly. No—that’s it. I left uncomfortable with what I’d seen. Not the bodies, but the crowd. When I got back to my flat, I found that my discomfort had turned to disgust.”

“Certainly,” the old man replied, nodding slightly. “Yes. It is complicated. All very complicated.” He paused and brought his hand up to his mouth and coughed weakly, then thrust the same hand back down into the pocket of his brown tweedy blazer, bringing out a small ratty kerchief, which he used to quickly wipe the side of his mouth. He sighed and the sigh turned into a cough that sounded like a rattle. “What you must realize,” the old man said, “is that medical research and knowledge has always had this terribly complicated relationship with the public. The first anatomies, not just in Britain, but in ancient Greece, were conducted out in the open air, or arenas, like in a theater, where the word comes from. Operating theater. They were displays, yes. But also: a form of punishment. Only the most severe criminals had their bodies opened for all to see…” He coughed, then paused, and in the silence, the female student spoke again.

“Wouldn’t this be a form of punishment as well?” she said, gesturing toward Byrne’s skeleton. “Ah, yes, quite,” the old man said. “That’s the question, isn’t it? Now that you know him, even a little, know that he has a name, does it seem fair that you should see his bones?”

“But even if he didn’t have a name, or we never knew it,” the woman said quietly. The old man either didn’t hear her or didn’t want to. He turned and moved toward the next display.

I broke off, resuming my tour, wandering past more of Hunter’s collection, past row after row of bottled-up eyes, ears, and mouths; mounted backbones, leg bones, bones grown cancerous and gnarled, cabinet upon cabinet of the interior macabre. I came to a line of rooster heads, some with a spur growing out of the comb, and others with the human teeth that Hunter had grafted on. My mind kept wandering back to the giant’s skeleton, his rough frame, its strange inert slouch. I kept glancing back at what remained of Byrne’s poor figure. It had an abstract quality. It looked, I realized, inhuman. Byrne wasn’t Byrne. Those weren’t his bones. Those were the bones of The Irish Giant. There was a practical element to Byrne’s disembodiment: Flesh, being flesh, would rot if it wasn’t carefully preserved. Hunter had placed his fleshy specimens in jars filled with extremely flammable alcohol (jars that would, well over a century after Hunter’s initial bottling, catch fire, after a German pilot dropped a bomb on the building that housed the collection, destroying more than half of it). But there was something else. The strangeness of real bones, when mostly what we see are fakes.

Once, while floating through the subterranean caves in Disneyland’s Pirates of the Caribbean ride, a friend—a Disney fanatic—had leaned over and told me that supposedly, one of the skulls set in a tableau of bones was real. Of course, we then debated which of the skulls we were looking at was most likely the real one and decided, counterintuitively, that it was the skull that looked slightly wrong—a little off—in context. The real skull had to be the misshapen one, a few shades darker than the others. The rest looked too much like skulls to be real skulls. Byrne’s skeleton gave the same feeling. A skeleton so large and strange that it passed from the real to the surreal and back again.

Nearing the museum’s exit, I passed its small gift shop and saw the old man standing behind the register. He wasn’t a professor, then: He was a docent. He was talking to another patron about the Hunterian’s upcoming closure, which would be temporary but would last several years. The building we were standing in, he explained, would soon be undergoing a massive remodel. Hunter’s collection—jars and bones and all—would be moved off-site, placed in storage for some time. Some items, like Byrne’s bones, might not ever appear in public again. The museumgoer chuckled and told the old man what a shame this was, doubly so because they didn’t allow photographs, and now no one would believe him when he told them what he’d seen in this place. The old man mentioned that they sold several nice books on the collection, and he was free to purchase those if he wanted.

Hunter told his students that what they would see in his surgical theater and anatomy lessons was not to be mentioned outside, in public. “Particular care should be taken, to avoid giving offence to the populace, or to the prejudices of our neighbours,” he told them. “Therefore it is to be hoped, that you will be upon your guard; and, out of doors, speak with caution of what may be passing here.” Hunter was warning his students of a simple fact: that people are disturbed to hear about the cutting open of dead bodies. But Hunter knew, too, that people were fascinated by it; after all, here I was taking in his strange collection in a museum bearing his name.

Hilary Mantel wrote a novel inspired by Charles Byrne and John Hunter. In it, Byrne is renamed, cast in the title role—The Giant, O’Brien, a dreamy fellow who tells tales by the firelight. Hunter is still named Hunter, a man driven half-mad with an insatiable urge to own the flesh and bone of beast and man, to experiment and dissect until he has discovered “the frontier of death.’’ In the novel, the Giant represents the Old Way, mythically large and filled with folklore. Hunter is, of course, the New: greedy, violent, cerebral, unfeeling—a collector; a scientist; a capitalist. The great tragedy that befell Byrne and O’Brien didn’t end when the subject died. Death could not even deliver him his final wish—that he would, at last, be freed from the prying and prodding public.

Even now, on the page, I’m dredging up the poor old Giant’s bones. And Jane Crawford. And Frank, to a degree. For her book’s epigraph, Mantel chose three lines from the Scottish poet George MacBeth that make clear how, while we may cheer for the Giant, we—and writers, especially—are more like Hunter than we might care to admit.

… But then

All crib from skulls and bones who push a pen.

Readers crave bodies. We’re the resurrection-men.