Grammar, with its mixture of logical rule and arbitrary usage, proposes to a young mind a foretaste of what will be offered to him later on by law and ethics.

— Marguerite Yourcenar, Memoirs of Hadrian

They trickled in—five, fifteen, then twenty-five—into a tiny classroom crammed with swing-top desks and worn-out workbooks. They’d just finished with breakfast—rice, chickpeas, a hard-boiled egg—or picking through the resources room: donated clothes, shoes, razors, toothpaste, tiny bars of hotel soap. They took their spots with a quiet hello or tentative smile, unsettled perhaps by the new teacher grinning back at them and repeating, “Welcome! Welcome! Nice to see you!”

It was early September 2015, and I’d been in Rome less than a week. I’d come for a year-long fellowship, to live in a palazzo on a hill, enjoy some “studious leisure,” get my novel written. But it was also the height of what came to be known as the European migration crisis. I’d contacted a refugee resource center here in the city, asked if I could volunteer, and was surprised to learn they needed English teachers.

“My name is Will,” I announced, giving the class the template. “I was born in England. I come from America. I speak English, French, un pochino d’italiano.” The last few students were wedging themselves into desks, backpacks still on. I gestured to a guy in his midtwenties sitting to my right. He had a thin mustache and his right arm propped up stiffly on the desk. “Please, your turn.”

He squinted at me, looked around for help.

“He wants you say your name,” another student offered.

Before he had a chance, someone else jumped in. “Yes, hello, teacher, first I would just like to introduce myself to—”

“Excuse, please”—a fourth student was holding up an old, well-creased worksheet—“what is the meaning of this word, un-re-li-a-ble?”

In this room, I’d soon learn, I’d regularly see students from a dozen or more countries. Senegal, Pakistan, Iran, Iraq, Mali, Nigeria, Burkina Faso… I often lost track. Some held advanced degrees back home. Others, like the student with his arm propped up—Sarwar, Afghanistan—were near illiterate.

I came to a balding man in his forties and, over-enunciating, asked his name and which languages he spoke. He was Ahmed and—Arabic, Pashto, Dari, English, Italian, French, German, Norwegian. Later, he’d tell me he’d been a translator for the US Marines and had fled Kabul under threat of death, picking up new languages while trying to live and work in the more prosperous northern European countries, only to get serially deported back to Italy.

“I am from nowhere,” he concluded gruffly, already bored. “A citizen of nowhere.”

I tried to push on, to a basic lesson about other ways to say, “How are you?” What’s going on? How’s things? What’s happening? What’s up?

“What’s…up?” Sarwar repeated, squinting.

“Come va,” Ahmed translated.

“Ah, certo!” Sarwar said, brightening.

“Please, English only,” I said. Over the weekend, I’d read that this was the best way to run an ESL classroom. And besides, I’d be lost if I let too much Italian in. It’s all too easy to think non-native speakers a little naïve, a little slow, until they switch to a tongue you don’t know.

A minute later, the door opened, and an African guy poked his head in. “Excusez-moi, c’est la classe d’anglais?”

“Oui, oui,” I said in wretched French, trying not to look naïve myself. “Bienvenue!”

The center was the crypt of an Episcopal church—“la chiesa Americana,” locals called it—part of a circuit of soup kitchens, NGOs, Jesuit charities, and leftist collectives picking up the slack from overwhelmed government facilities. The center was way too small to be a camp (most of the camps and squats were on Rome’s outskirts), but it could feel like one. It was loud: the constant chatter over tea or chess, the thwack and clunk from the foosball tables, dubbed action movies rumbling out of the TV room, the whir of clippers as the barbers finished another beard trim or a Mario Balotelli-style mohawk. And, well, it smelled. A couple of hundred men passed through every day, many of whom slept in parks or on the street.

It was not quite what I’d expected. I’d thought there’d be Syrians here. (Daniela, the volunteer coordinator, explained that Syrian refugees traveled through Turkey and Greece, and that the few who came to Italy were usually resettled elsewhere.) I’d thought there’d be women. Daniela pointed out that, because many women seeking asylum were vulnerable to sex traffickers, they were given housing in camps that didn’t send them out into the city during the day; the men’s camps, meanwhile, were closed from 8 a.m. to 8 p.m. in order to save money. Children? The heart-wrenching photo of Alan Kurdi, the Syrian boy who just that month had drowned off the coast of Turkey, was everywhere. But legally the center couldn’t serve minors. They, too, were in special camps. Almost all of our guests were adult men, maybe 80 percent of them under thirty, and most days the center practically pulsed with their restlessness.

Although a staggering number of Syrian refugees arrived in Greece in 2015, the North Africa-to-Italy corridor, for most of the last decade, has been the primary route for human smuggling into Europe. Even 2022’s mass exodus from Ukraine may end up a temporary statistical spike. In Italy, the “crisis” is endemic, a steady flow of asylum seekers from nations and regions—add Eritrea, the Gambia, Libya, Kurdistan, and Baluchistan to the list—whose turmoil only ever grazes international news.

Sea rescues, drownings, migrants suffocating in the backs of trucks, children locked up in cages. These stories anger and appall and move us. But for almost all of my students, the crisis had also come to mean something else: waiting. Waiting and trying to grasp the rules, the grammar, not just of new languages but of a new continent, one made up of a particularly labyrinthine network of bureaucracies and charitable organizations. And if I wanted to help my students, really help them, I’d have to learn that new grammar too.

My second, third, and fourth lessons were about work. “Everyone wants to know about work,” Daniela told me. The center ran a jobs program, kept a jobs board, helped the guys translate their résumés. In class, I did a role-playing exercise: “Hello, I run a farm. I’m looking for someone to help me farm. What experience do you have?”

“Hello, sir,” one student would answer. “I can help you. I am an engineer.”

Another would say, “I am air-conditioning man.”

“Yes, very good, I study medicine.”

From talking with Daniela, I knew the best work most of the guys would get here in Italy would be seasonal labor. Many of them knew this, too, but it didn’t seem kind to role-play picking olives or tomatoes for a paltry few euros a day. So, my farm did, indeed, require an engineer, or a doctor-in-training, or needed its air-conditioning system fixed, each dialogue ending with a gratifying “You’re hired!”

Perhaps we should’ve worked on correcting their verb tense. You were an air-conditioning repairman. You once studied medicine. Whatever credentials or skills the guys had back home meant little here; you needed a license, a connection, and/or an Italian high-school diploma for just about any job. (Never mind that Italy already had a 12 percent unemployment rate.)

At first I wondered why the guys weren’t in the classroom next door, where a kind, silver-haired woman taught Italian to a sparse few. After all, nearly all of the center’s guests had been “Dublined” in Italy. (The EU’s Dublin Convention mandates that the member country that first registers an asylum seeker must handle their application, meaning the migrant must stay there.) Most wanted to get to Germany, Norway, Sweden, or the UK, where there were said to be jobs and good services for refugees. But the numbers of asylum seekers accepted by even the richest nations constantly changes with the economic and political winds. Even those whose refugee status is incontestable—Syrians and now Ukrainians—often receive a stony welcome. At the center, we were constantly hearing about our guests going north only to find yet more unemployment and homelessness. You saw in the news, too, reports of migrants being pulled into drug dealing and smuggling. Even here in Europe, they were far from safe.

Still, the guys believed: English could take them where they wanted to go. Wherever they traveled, they could be understood; they could tell their stories. And if they had to stay here, many of the lowest rungs of the economy—handing out fliers for hop-on bus tours, selling bottled water and junky handicrafts to tourists—all but required English. The language could be a foothold, a way up, however slow and steep the path. Learning Italian, on the other hand, was admitting you were stuck, you were never getting out of this half-broke country. It was giving up on the European dream. “English is strong language,” Ahmed told me. “It make money all over the world.” I started to correct him—the correct collocation was “powerful language”—but he’d put it so succinctly I couldn’t quibble.

We ran the role-play again. “Welcome to the farm,” I said to Suleyman, another regular, the only one who came every week. He’d fled the second Liberian civil war in the early 2000s. Fifteen years in Italy, and he’d yet to find anything like steady work. “You’re hired!”

Sarwar squinted. “What mean…hired?”

“Is opposite of ‘low,’” Ahmed said impatiently. “Lowered, you see?” He put a hand down by his ankles then up over his head. “Highered.”

“Well…” I began.

“Ah, certo!” Sarwar said. He was Hazaras, an ethnic group oppressed even within Afghanistan. The Taliban had stolen his family’s land after they participated in a NATO-funded development project, and murdered his brothers and father. Sarwar had escaped. I didn’t know the details, only that he’d been given a spot in a Vatican-sponsored camp. The reason he squinted was that someone in that camp had recently stolen his glasses. As for his right arm, he couldn’t raise it above hip height; two years ago, at twenty-five, he’d suffered a stroke. It seemed unlikely he’d find the menial laboring work I was avoiding talking about—even if, back home, he’d been a farmer.

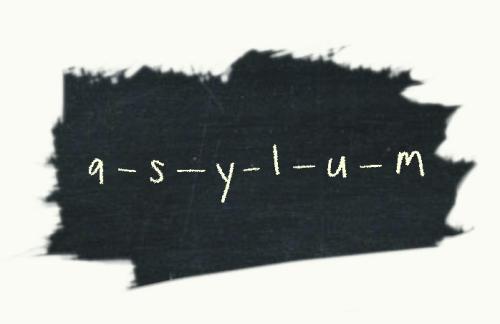

One of the most confusing words was why.

The guys understood what, where, how, and when. But why, the word itself, stopped us dead. Not every language has its equivalent. (Italian, French, and Arabic use perché, pourquoi, and limaadhaa—literally, “for what”?) But the real point of confusion was that “why” sounded like “y.” I’d be spelling out “d-r-y” or “a-s-y-l-u-m,” and someone would invariably shoot up a hand and say, “For what a why in this word?” (Never mind the convoluted history of “y,” a consonant, vowel, and/or semivowel, depending on context. It’s the “Greek i” in Romance languages—“i grec,” “i greca”—but the OED has its English origins as “obscure.” Even as a syllable, it’s confounding.)

Another big problem with “why” was that it brought us straight into the abstract. Other interrogative terms typically solicit specific information. Where does this bus go? When is lunch? How do I get to the train station? Why, on the other hand, brings us to causality and complexity but not always clarity. The causes and effects that ruled my students’ lives were so tied up with the vagaries of geopolitics that they had both the diagrammable logic of a sentence and the fluidity and chaos of the weather. Why didn’t the northern European nations, which have the most resources, do more to relieve the burden of the crisis upon southern European nations, which have the least? Why did every right-wing politician rant about bootstrapping yourself up, yet demonize immigrants for trying to do just that? Why did Norway accept so many Afghans one month and almost none the next? Why would Belgium give your wife and children asylum but deport you?

Many of the guys were eloquent on these subjects, despite language barriers. There were many explanations: Nativist politics were now rampant across the EU. Accepting refugees was expensive, and western and northern Europe had long fallen short on commitments to resettle displaced persons. Husbands and fathers frequently came alone to Europe hoping to get asylum and bring their families later, only to get Dublined in a different country than their wives and children. But none of that brought much comfort to the group.

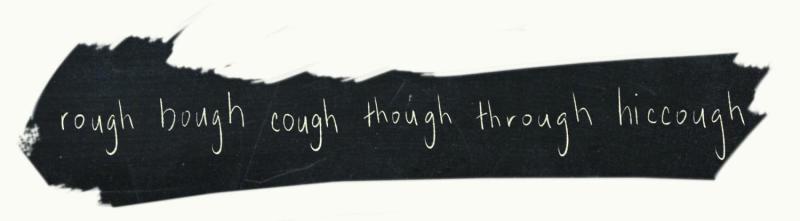

More and more, I found myself sticking to smaller questions in class. But even these presented grammatical bafflement. We spent hours on count nouns and mass nouns. How many euros is it? How much is the price? Or the maddeningly irregular way prepositions are used: Ride on the bus, but in the car. Eat breakfast in the morning, have dinner at night. Or why we regularly pronounce the ough tetragraph (rough, bough, cough, though, through, hiccough) six different ways in American English (and nine in British English). Suleyman threw his hands up at this: “For what? English crazy language!” What else can you say about a linguistic system that purports to be orderly but is actually cobbled together from the tongues of all of the conquerors of the British Isles—Latin, Norse, Celtic, Anglic, Saxon, Frisian, French—and also takes its promiscuous vocabulary from the languages of all of those the Brits conquered in turn—Persian (pajamas), Hindustani (bungalow), Algonquin (hickory), Swahili (safari), Kikongo (goober)—meaning it’s not systematic at all but just a grab bag of rules, exceptions, and flat-out, yabbering (yabber, from Australian aboriginal Wuywurung), mind-pulping contradictions?

And yet, as with Latin, linguistic imperialism can also lead to a useful common tongue. The beauty of modern English, I sometimes thought, is exactly its impurity, our willingness to take on new words and new dialects, even when they trouble the fastidious ear, new ideas and new experiences, even when they unsettle our complacent souls. Not the promise of one language for all, but many languages in one. Even still, for a learner, this all adds up to English being confusing as hell.

“For what?” Suleyman kept asking.

“We just do,” I kept saying. “It just is.”

After two months at the center, I had plenty of my own whys, too, and I looked to Daniela for answers. Why eggs, chickpeas, and rice for breakfast, every day, day after day? Low cost, high protein. Why did so many of my students smell like smoke? Because they were sleeping rough at night, next to campfires. Why did the resources room stock so much skin cream? The African guys had trouble with their skin cracking in this new climate, especially now that winter was descending.

And, of course, there was the big why, the one all of the guys had to answer at some point, whether in a UN asylum interview or just with a curious volunteer. “Try not to fish for trauma,” Daniela told us. But it was always tempting to ask: Why are you here? Why leave your home? Why risk everything—life, limb, getting hassled by the Carabinieri almost daily—just to end up in this dingy church basement?

Some, like Ahmed, told their stories freely. Other stories, like Sarwar’s and Suleyman’s, you heard through the grapevine. But on the whole the guys didn’t talk much about “those things.”

And what about me, my students asked. Why was I here? Some assumed I worked for the Italian or American government. Explaining that I’d written a couple books and some rich people had given me a prize to come to Rome wouldn’t have cleared up much. As an immigrant myself—England, Ireland, Wisconsin—I believed that your birthplace shouldn’t be just a line on a form telling you where and how far you could go. And I had my journalistic curiosity—though I’d quickly given up on doing any reporting here. The center constantly had professional and amateur journalists alike asking to come in and shoot footage or interview the guys. Daniela was also besieged with requests from American tourists who wanted to “do something” on their vacation. It was hard for her to disappoint well-meaning folks, but unless they wanted to donate money or food or clothes, there was little they could meaningfully do in a couple of days or a week.

Were we all just enacting a white-savior narrative? Most of the other volunteers here were white. (Though the center had been founded by a Ugandan minister, in the 1980s, and the migrants it served for the next thirty years were more likely to be Albanian, Romanian, or from the former Yugoslavia, than to originate from the Middle East or Africa.) This place did attract savior-types. But they tended to burn out quick. Many of the staff were years into this work, and they struck me as tough, practical, and jaded. They despaired at the scale of the crisis, the idiocy of governments, and the naivety of the guys who’d expected Europe to be a paradise—and they kept grinding at it anyway.

“I like teaching here,” I told my students. “It makes me feel, I don’t know, useful.”

The guys wanted help, and it felt good to give it, even if this was the most chaotic classroom I’d been in. We couldn’t afford a common textbook, and lesson planning was pointless given that my roster of students changed every week. Among my regulars, Suleyman and Sarwar were making almost no progress, and Ahmed was only growing more bitter. English might make money all over the world, but we were constantly welcoming guys Dublined back from the north. Better that they work on their Italian. Better that I get back to the palazzo, my brilliant fellow fellows, the beautiful food, the free-flowing (and free) wine, the novel I’d come to write. Let someone else try to explain phrasal verbs, quantifiers, prepositions, collocations, and every other nonsensical rule; let them chip away at the giant, unanswerable “for what?” That November, after almost every class, I wanted to quit.

And then I met Lamin.

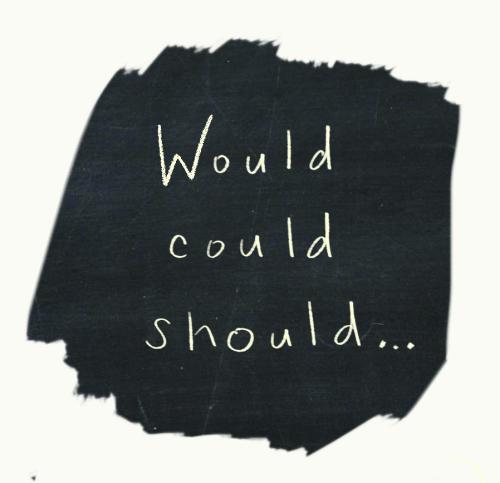

He arrived somewhere between would, could, and should.

It was after Thanksgiving, and the lines for breakfast and the resources room often stretched to the door, the guys desperate for winter coats and sleeping bags. We’d done lessons on travel, family, what to do when you’re sick or hurt. But travel seemed to remind everyone of the places they couldn’t go and family they couldn’t see, and illness and injury were specters I hated to raise. Sarwar’s withered arm wasn’t going to get any better. Another student, a Libyan, had an agonizing limp; in a firefight between rebels and Gaddafi loyalists, he’d been a bystander and had half of his right calf shot away. Suleyman, perhaps to get through increasingly frigid nights sleeping in the streets, had been coming in drunk, and with a hacking cough. I was trying to find some distraction in pure grammar. But for three weeks we’d been utterly jammed up on our current lesson: the conditional.

If Hamid hadn’t sold his transit pass, I’d write on the board as the guys furrowed their brows, he wouldn’t have had to walk two hours to the center. A native English speaker can toss off such a phrase without a second thought. But the logic—things that might not have happened in the past if only something else had or had not happened in the more distant past—was difficult to parse. Never mind the truly theoretical: If I were you, I’d study Italian. “I were…you?” Sarwar kept saying. “But…aspetta, wait…you are you, sì?” Even Ahmed, always so confident, just gave up in disgust. (He’d been skipping class, usually to hit up drop-ins for cash. “I need bus ticket. Five hundred euros. I want go to Paris. Five hundred, my friend, you have it.”)

The only one eager to brave the conditional was Lamin, a West African who immediately stood out by his dress. Most of the younger guys wore knock-off Adidas jackets, faux-designer jeans with lots of careful rips and fraying, Chicago Bulls or Miami Heat caps perfectly askew, earbuds dangling over ears. Lamin usually had on pressed slacks and an Oxford buttoned all the way up, a school uniform of sorts. He was twenty-four, slight, shy. Yet his hand went up before anyone else’s. He raced ahead on the exercises and, after we finished, wanted to keep working. I started tutoring him—two, three times a week. He was making progress, quickly recovering, it seemed, things he knew and had only forgotten. I tried not to ask questions, but invariably found out the whys.

Back home, he’d been studying education at the University of the Gambia. For more than twenty years, his country had suffered under a strongman, a crippled economy, political arrests, indefinite detentions, torture, assassination of journalists, and political murders. Lamin came from a family active in the opposition. He’d attended a protest; the secret police came for him. He fled to Senegal, then Mali, found work with a small-goods trader running a truck across the Sahara into Libya. In the middle of the desert, Lamin was kidnapped and held in a shipping container. When the full midday sun hit, it was hell. He kept trying to explain that his family could pay his ransom. But none of the guards spoke his languages (Wolof, English, Jola, Fula). Finally, a new guard came along who understood English. Lamin was able to call home. After eight months, he was free.

He worked odd jobs, hired a man to drive him north, got delivered instead to another kidnapper: two more months of imprisonment, another ransom, paid for by his labor on his captor’s new house—Lamin building, in effect, his own jail. Next, he went to Tripoli. There was gunfire in the streets, and he had to bury his money outside his boarding house to keep from being robbed, but eventually he raised enough to pay a smuggler. A half mile from shore, the boat started sinking. Lamin could swim. He helped those who couldn’t. Nearly thirty drowned.

Four months later, he tried again. What choice did he have? Staying in Tripoli or trying to go home would’ve been even more dangerous. The second boat left early on a December morning, 2014, and soon got lost in the Mediterranean. An Italian rescue vessel finally located them. Lamin was fingerprinted, registered as an asylum seeker, and sent to a “welcome center” in Catania that housed four thousand. Six months later, he was given a train ticket to Rome. For weeks, he slept in a park overlooking the Colosseum. Then he found a camp. Someone told him he could get breakfast, warm clothes: Just go to la chiesa Americana.

And now here he was, eagerly filling in the blanks on If Adama _________ the lottery, he will buy a new car and I wish I _________ more time to relax, improving every time we worked together. But as we pushed on to the zero and mixed conditional, Lamin struggled. His schooling had been in English, but his first tongue, Wolof, conjugates very differently. He could put the answers together but never quite fit them into his own conversation. If I go home for the holidays, I _________ my mother a kiss. If I _________ meet the president of my country, I would tell him _________. Just generic questions on a worksheet, yet Lamin and the other guys struggled. Or I struggled to explain.

Would, could, should—this was the language of possibility, of opportunity. Up at the palazzo, if you knuckled down for the next six months, you would finish your novel, your dissertation, your new group of paintings. You could get a book contract, an exhibition of your works. You would find a job as a professor, then, should you want to, get a mortgage, make a home, raise a family. Hopes, dreams, plans: You used the conditional to conceive them, take them from imagination into reality.

Down at the center, half our lessons posited a better future. If Omar improves his cooking, one day he will open a restaurant. But the path from here to there was anything but straight. Even the guys who barely spoke Italian knew, intimately, an Italian phrase: sempre in giro. “Always around” or “always in circles.” They were forever killing time, making the eternal circuit of soup kitchens, bouncing from camp to camp. Even getting enough of a permanent residence to open a bank account or receive private mail was a goal that eluded most of our guests. Then, if you succeeded in getting a bank card or your permesso—a permit of stay that requires a bewildering number of forms, stamps, and signatures—there was a good chance it’d be stolen in the camp. The guys could plan out a future, but mostly they were stuck constantly circling in the present.

And the past? I thought about Lamin’s journey. In a place like the center, where there are people who can help, such stories can be currency. And sometimes that currency can be forged. But I never detected a trace of cynicism or guile in Lamin. He told his story freely but distantly, never lingering in it. He must have had many moments he would like to have changed, from the day of the protest on, and much time—almost a year in captivity—to rue them. But perhaps if he lived in that mood, if he dwelled in that twilight of ifs, he might never escape it. When speaking of the past or the present, Lamin tended toward the simple tense. We also use the conditional, after all, to talk about regret.

After a year, Hamid found his feet in Rome. Adama’s friend sold him a new phone for a song. Sissa was able to get his documenti in six months, even with all of the red tape. I tried to keep the names familiar, the scenarios optimistic. For Mamadou, learning English is a piece of cake. The point, I hoped, was that every language has idioms and proverbs so idiosyncratic all you can do is shrug or laugh. And we had a good time. The guys knew plenty of equivalents in their own tongues. Dari: Haste is the work of the devil. (Haste makes waste.) Arabic: Give the dough to the baker, even if he eats half of it. (Go with the expert, even if it costs more.) Sharing these expressive little curios, the stuff that knitted together daily life, felt somehow profound—especially when, back in the US, a presidential candidate was blathering about Muslims cheering the Twin Towers coming down, about terrorists among the invading hordes of migrants. That winter, one college group after another visited the center, fresh-faced, voting-age kids who got to see firsthand what refugees (and Muslims) actually looked like. Or, anyway, it was weirdly gratifying to witness Midwestern frat boys square off against West African day laborers on the foosball tables. Put yourself in their shoes, we told the college kids, and you’ll understand.

Most of the guys, even if they wore the same clothes day after day and lived in camps or squats with one shower and one iron among a hundred, kept as fresh and rakish as they could. They were young, proud, and lonely. Yousef wanted to talk to the woman, but the cat had his tongue.

“Okay,” I said, “here’s another one.” Money doesn’t grow on trees, I wrote on the board. The Middle Eastern guys smiled and nodded. Yes, yes, they all knew this expression. But the African guys weren’t so sure. “What do you mean?” one protested in a percussive accent. “Of course money grow on trees. I plant orange tree. It grow oranges. I sell oranges.” Several of us were laughing, but he was steadfast.

And he wasn’t wrong. A lot of the guys participated in a ground-level economy that tourists and most Italians would never see. You traded cigarettes for a Bulls cap, your backpack for a place to stay for the week, your mobile phone, if you were truly desperate, for a sleeping bag. And there were orange trees dropping fruit all over the city. You just had to hustle.

“Yes, trees grow money,” my student insisted. “Lots of money.”

I could see Lamin trying to push against sempre in giro. For two years, his life had been mere survival. Now, maybe, he had a chance to move ahead, not just in circles. Most of my students left by two in the afternoon, so they wouldn’t miss lunch at a Jesuit soup kitchen near Piazza Venezia. Lamin kept studying. He wanted homework, resources on the internet. He wrote short practice essays, brought in newspaper articles with words he didn’t know circled. Eight months in that storage container in the Sahara, trying every day to speak with his captors—English, the “strong language,” had gotten him out. How far could he go if he truly mastered it?

Daniela had been in touch with an American college across the Tiber River interested in sponsoring a refugee student. It was only a possibility, but when we mentioned it to Lamin, he doubled his efforts. I got excited too. We didn’t have many victories at the center. Two of my students had found under-the-table jobs, one washing dishes at a pizzeria (we were working on translating the menu, in case a waiter position came open), the other as a guard at a parking garage, where he slept in a van owned by his boss. Somewhat heartening news, though they were both only getting ten, twenty euros a day. But enrolling Lamin at an American-accredited college, so he could get a degree that meant something both here and abroad—now that would be a win.

First, however, there were the entrance exams. Grammar and style were taxing enough. Now, suddenly, there was also the entire matter of Anglo and European culture. Once, in class, I used a passage from an old workbook, a spot-the-mistakes exercise: The iceberg make a big hole in the side and the Titanic begin to sink. Some people survived because he got into a lifeboat. Many other peoples died when they will fall into the freezing water. The first real mistake was my grabbing a lesson about people drowning, but that wasn’t what the guys were hung up on. “Titanic?” Suleyman asked. “What mean Titanic?” Not even Lamin had heard of this most infamous of Western disasters. The American and British college-entry tests were worse: the Emancipation Proclamation, Marie Curie, the Grand Canyon, Alpine skiing, Sherlock Holmes. These cultural touchstones were another fluency I took for granted—and, for Lamin, yet more obstacles to clear.

“Hello,” I said, playing the eligible woman, “how are you?”

“I am very well,” one of the guys would reply. “It is a beautiful day.”

“I love Rome in the springtime. Are you from Italy?”

“No, I am from”—Côte d’Ivoire, Benin, South Sudan, Cameroon.… It was late March 2016, and the longer I worked at the center, the more various the guys’ countries of origin seemed. Sarwar, Suleyman, and Lamin were still coming regularly, but Ahmed had been a ghost, only coming in now and then to grab an outlet to charge his phone. “Do you know my country? I take you one day!”

“I’ve never been,” I’d answer, continuing the role-play, “but I hear it’s very beautiful.”

“Tell me, please, where the place you come from?”

Usually I would say Poland. The guys were especially interested in Polish women. They supposedly had “more traditional” values and featured in the myriad Facebook groups claiming to connect “Arabic Men with European Single Girls” or “African Men with White Women Who Love Them.” Online, I’d noticed several of my students in these groups. You heard stories about women (or whoever was on the other end of those Facebook chats) who were so concerned about refugees, who just needed to reach out to one, especially when he was so handsome, long-term flirtations turning into virtual engagements, send a ring so I know you’re serious, send a ticket to Rome so I can finally meet you, the whole thing so tantalizingly close to fruition—until she never actually landed, and the ticket got refunded for cash.

“Poland also very beautiful,” my student would go on. “I see many beautiful photos.” Here, he’d pause, concentrating. “You are very beautiful. You have boyfriend?”

“Okay!” I said, breaking character. “Good, very good. But piano piano, slowly slowly. European women like to be friendly first.” And then, among other wretched advice, I suggested less abrupt approaches: What do you do for work? Do you live in the neighborhood? Are there any cafés you like in the neighborhood? Would you like to have a coffee at one of those cafés? The guys found this kind of circuitous talk funny. Either because many came from cultures where men and women didn’t mix so casually or, just as likely, because the idea of such interactions made them nervous.

The stakes, after all, were high. Meeting a woman, chatting with and maybe charming her, a date, a relationship, marriage, citizenship, permanent residence, a chance to live and work anywhere in the EU, to finally leave Italy—it was the best, or the fastest, way out of sempre in giro. And it had happened. One volunteer—an American, even better—had married a guy from Côte d’Ivoire. There was a reason the young guys dressed so natty at the center.

The older guys, however, couldn’t hope for such a miracle. Suleyman and Ahmed were both in their forties. Living on the streets had grizzled them, made Suleyman shy and defensive, Ahmed touchy and truculent. They didn’t dress for style but to get through the night. Their shabby clothes, shuffling gaits, and, frankly, their odor marked them out, made them all but unemployable. The younger guys shunned Ahmed—he was becoming a pariah—but they seemed both fond and wary of Suleyman: If they, themselves, couldn’t figure out the hustle, a similar fate awaited. The center could be an intensely macho space, but the fierce competition over foosball or ping-pong also betrayed deep wells of frustration and fear.

The older guys, however, couldn’t hope for such a miracle. Suleyman and Ahmed were both in their forties. Living on the streets had grizzled them, made Suleyman shy and defensive, Ahmed touchy and truculent. They didn’t dress for style but to get through the night. Their shabby clothes, shuffling gaits, and, frankly, their odor marked them out, made them all but unemployable. The younger guys shunned Ahmed—he was becoming a pariah—but they seemed both fond and wary of Suleyman: If they, themselves, couldn’t figure out the hustle, a similar fate awaited. The center could be an intensely macho space, but the fierce competition over foosball or ping-pong also betrayed deep wells of frustration and fear.

Few of the guys seemed to enjoy relying on charity. Other than Ahmed, none of my students ever asked for money. If I offered to buy Lamin, Sarwar, or Suleyman even a slice of pizza, they immediately waved it off. I sensed it often, a deeply wounded pride bordering on communal depression. If confidence is attractive, it became harder and harder for the guys to sustain it the longer they stayed in Italy.

So we role-played both the ask and the response to polite rejection. “Yes, thank you, I would also like to be friends.”

That April, the college across the Tiber River agreed to enroll Lamin. He’d have to take introductory English, to make sure he was prepared for regular coursework. He’d barely scraped in, having scored just well enough on the entrance exams we’d practiced. This was all provisional; they’d have to reevaluate midyear. But a win was a win.

To celebrate, I took Lamin and two more of my best students to Multisala Barberini, a theater where new Hollywood movies played. A chance for the guys to blow off steam, veg out, bond a little—and practice listening comprehension, hear some unfamiliar voices. I chose something big and loud and silly: Deadpool, a satire on superhero movies. Two months to go in my fellowship—I was missing America bad, and Multisala Barberini almost made you feel you were home. I bought us all popcorn and bucket-size sodas, settled in for the show: characters stabbed, maimed, skewered with swords, diced into pieces; heads cut off and kicked around like soccer balls; a long, grisly torture scene in which a hero is essentially boiled alive. On my own or with American buddies, I probably would’ve laughed my ass off. Now, I thought about Lamin imprisoned in that shipping container, about Sarwar’s murdered father and brothers, his withered arm, about another Afghan I knew, kidnapped and tortured for ransom, about my Libyan student who, unlike the movie’s heroes, hadn’t just brushed off a gunshot but dragged his badly healed leg through the streets of Rome day after day.

Afterward, Lamin and the others thanked me, but in many ways the movie had been beyond them: its wordplay, its pop-culture references, its casual cruelty. Back home, most of us are so cocooned in irony that we can laugh at a certain kind of violence. I’d spent my whole life learning the language Deadpool spoke, its sly, multilayered allusions and sardonic pseudo-jokes. It could be ghoulish, but I also missed that fluency. The stunted, clunky English I used with the guys was often painful to me. Back home, I wouldn’t have to think about every rule, every exception to every rule, everything this cultural grammar gave me and kept from them.

One of the last classes I taught that year was on the simple future. In the labyrinthine, contradictory, often plainly nonsensical systems of English, the simple future is pretty user-friendly, the relationship between cause and effect straightforward and certain—subject + “will” + infinitive—even if the things it expresses may not be. When Hamid gets his Italian citizenship, he will go to find work in Germany. (Citizenship requirements—proof of income and five years legal residence in Italy, among others—were virtually impossible for the guys.) I’d hoped to give my few regulars a confidence-building lesson, show them how far they’d come, and to offer the new faces—summer again, meaning crossings of the Mediterranean were back up—something digestible. But everyone struggled. My regulars’ lives were just too chaotic, and half of the new guys probably should’ve been in basic literacy. It was one of those weeks when everything—our classes, job programs, asylum-application assistance, and family-reunification efforts—just felt futile.

I’d been thinking, hard, about staying in Rome, devoting myself to the center. But I had a job to go back to. And Lamin was about to start school (“I will succeed,” he promised Daniela and me). I hoped he’d find support from the college and his new professors. When we’d first started studying together, we had a little routine. “This is my hero,” I’d say, pointing to Lamin. “This is my hero,” he’d say, pointing to me. It made me feel good, and uneasy. I’d really only been there to reassure him. Most of the work he’d done on his own. It was as good a time as any to go back.

So I did. And everything fell apart. After a year at the palazzo, living among brilliant, engaging scholars and artists and feeling useful or, at least, purposeful at the center, I abruptly found myself alone in Chicago’s concrete prairie, bereft of Rome’s burnished light and shaggy green hills. Everything I’d seen the guys go through, and I was miserable? Lamin regularly messaged me on Facebook and WhatsApp. He was already falling behind in coursework, his confidence dwindling. I tried to tutor him, but the time difference made it difficult to stay ahead of his daily homework. Then I got too busy to help. Then the election came.

Obama’s reserved, professorial manner gave way to Trump’s schoolyard bullying, and the language of compassion prompted by the 2015 crisis was drowned out by “Build the wall!” In Hungary, Viktor Orbán, busy building his own border fence, referred to migrants as “poison.” Marine Le Pen, about to launch her second campaign for the French presidency, had long talked about “an organized replacement of our population.” And Matteo Salvini, soon to be Italy’s Deputy PM and Interior Minister, called for a “mass cleansing” of migrants, “street by street, piazza by piazza.”

Back in the US, posters were appearing in shop windows—refugees are welcome here—with an illustration of a Syrian man cradling his child inside his coat. I went to a protest at O’Hare where more than a thousand people rallied against Trump’s Muslim ban. This was the power of free speech at work, and I felt temporarily shaken out of my funk. But the truth is that, with the exception of Germany, no Western nation accepts anywhere near the number of refugees from Africa and the Middle East as Lebanon, Jordan, and Turkey, where the largest camps remain. We might say that refugees are welcome, but, especially in the US, we see relatively few of them. I believe profoundly that clarity of expression and clarity of purpose go hand in hand, and it feels good to protest or put a poster in a window. But what solutions do we actually offer? In the end, is it all, on the right and the left alike, mostly rhetoric?

That December, I returned to Rome and substitute taught. I took Lamin out to dinner. He seemed more tentative than ever. He liked his new professors, but they held him to account on his written skills. He wanted to be closer with his classmates, but they were mostly Italian and outside of class spoke only Italian. It seemed, too, that Lamin had internalized the months and months of the Carabinieri stopping him, checking his papers, finding every opportunity to make him feel like a straniero, even if he’d been in Italy nearly two years now. That night, as we parted ways, an old guy came up to us and muttered something in Italian. “What are you doing here?” Lamin thought he said. The man had simply asked directions.

That same month, there was news from the Gambia. Yahya Jammeh, the dictator who had run his country into the ground for twenty-two years, lost his bid for reelection. After a few weeks of refusing to accept the poll results and threatening conflict, he fled the Gambia and went into exile. I spoke to Lamin on the phone. He was elated.

Soon after, Lamin passed the oral section of his English final. But he failed the written. Through the rest of the academic year, he continued to struggle. It didn’t help that his camp was an hour and a half, by bus, from campus, or that he had three roommates and lights out came at 10:30 p.m. I suggested he use the campus library to study, or other libraries or cafés around the city, but he shied away from such places. Everywhere he went, he could see people thinking, “What is this African guy doing here?”

He wanted to get a quiet room somewhere but didn’t have the cash. He found himself asking for donations at the center, but what he needed for a semester’s rent was enough to buy forty sleeping bags for the homeless guys, and that’s how the money got spent. Lamin kept on struggling at school—he failed his spring exams as well.

And something else made it harder for Lamin to argue his case: Technically, he was no longer a refugee. Political prisoners in the Gambia were released following the election. The secret police, gone. On humanitarian grounds, there was no reason he couldn’t return. But what would he go home to? More than twenty years of misrule had wrecked every social and economic system in the country. The most desperate and ambitious alike are still leaving.

Up until the pandemic, I returned to Rome often, to substitute teach or work on small projects that, soon enough, got erased by the general chaos of the center. For about a year and a half, Sarwar was there, sitting right up front, still squinting at the board—he never could keep a pair of glasses—as he strained to follow the lesson. Then we started seeing less of him. We heard that he’d been placed in a scuola media (middle school) program, or been given some janitorial work in his camp, or maybe he was just getting breakfast elsewhere. The few times I did see him, we exchanged a few broken pleasantries, then he’d smile and murmur, “Thank you, nice meet you, goodbye.” No one, not even the other Afghans, really knew Sarwar’s trajectory. He was just around, sempre in giro, still doggedly making the circuit, only in a different orbit now, further and further away from us.

For a time, I lost track of Ahmed, too. I heard he’d been up and down Italy—Milan, Turin, Palermo, Padua—looking for work. I heard he’d gone to Denmark, where, apparently, he had a wife and kids. I heard he’d simply been asked to stop coming to the center. But then he was back again, bugging drop-ins for cash, telling them he’d been a translator for the Marines, promised a visa by the squad commander, left behind after all of his American friends pulled out, and that the Taliban, al-Qaeda, they all wanted to kill him, et cetera. Not that I disbelieved Ahmed, but I had learned more about him: The Afghan guys claimed he was actually Pakistani, pushing him down the ranks of who qualified as a refugee. But the Pakistani guys didn’t accept him either, wouldn’t even let him join their fierce games of chess. Whatever his story, Ahmed eventually told it to the right drop-in: A retired Canadian real-estate investor gave him three thousand euros, enough for Ahmed to get himself smuggled to Cyprus, where, supposedly, he knew someone who could get him work.

After that, Suleyman was the only regular. Though he still sometimes showed up drunk, got flustered by the lessons, and never really advanced, everyone had come to love him. He was bearish, good-natured, consistent. Looking back, I suppose he came out of habit, to have somewhere to be, to make the days and weeks and months seem like they were adding up to something. Often, he sat in his tiny desk half-asleep, unshaven, red-eyed, hardly able to pay attention. Once, on my way to a weekend in Bologna, I saw him at the central train station, huddled on a bench in his shabby coat. I called his name, and he looked up, grinned blearily. I lingered to talk, but I couldn’t quite understand him, and the conversation came to an abrupt end. The following Monday, there he was in class again, still showing up.

Lamin’s coursework at the college went online through the pandemic; he was lucky to be living in an apartment with consistent internet access. He’d also started delivering food, which kept him steadily employed during lockdown. Meanwhile, the center closed down regular operations and became simply a pick-up point for the guys who needed a brown-bag meal or a change of clothes. Some but not all camps extended their hours to serve their guests during the daylight hours, but a lot of the guys eventually drifted away, likely to other parts of Italy or north into the rest of Europe. Meanwhile, the whole world got a taste of sempre in giro: waiting, waiting for things to change.

For Lamin, after six years of study, they finally have: He graduates this summer with a degree in international affairs. He’s also taken on part-time work at a Jesuit-run refugee resource center, helping teach basic IT skills to their guests. When I speak to him now, I hear that he’s surer of himself, more cautious, perhaps, of others. Assuming Lamin’s degree leads him to steady, full-time work, he’ll become one of our community’s real success stories, whether he stays in Europe or returns to the Gambia. To get this far, he’s had to learn the grammar of two continents—the lawlessness of the Sahara, the coldly indifferent bureaucracy of Europe—and the sprawling vocabularies of American, British, and Italian culture. The future is uncertain, but he’s well-equipped to meet it. I’ve noticed, too, that he uses less “might” and more “will.”

Still, it’s Suleyman I think of most. In summer 2018, he disappeared. No one at the center, guests and staff alike, knew where. His mobile went to voicemail, no response on Facebook. Lamin tried to reach him through mutual friends. Nothing. Everyone was surprised, worried. But then so many guys just disappear one day, to chase rumors of a job, only to line up for the same soup kitchens, sleep in the same parks, just in a different city, or to climb into the back of a smuggler’s truck, their scant savings spent on another last-ditch effort, becoming, again, human freight to be traded and preyed upon, their bodies their only value, their stories having no currency at all.

What Suleyman knew of the “strong language” he’d never been able to make work for him. English could help take down the barriers to a better life. Or it could be its own wall, stretching ever higher, the future continuous and always just out of reach. The accident of where we are born, more than anything, is expressed in how we speak, and, at the center, the ability to tell your story to the right person at the right time meant a great deal. Often, I suspected Suleyman wanted to stay after class for help. But I was too busy with Lamin, whom I understood on more than one level, and it was too easy to let Suleyman, after a halting exchange, wander back into the unforgiving streets. Anyway, the best I ever had for him, when yet another crazy rule presented itself, when the whole damn system twisted into utter illogic and absurdity, was only to say what I always did:

“We just do,” I’d tell him. “It just is.”