Until her father died, Sissy Willard’s parents took her and her two brothers out of school every year at the end of April to spend a week in Kitty Hawk, and every year they stayed in the same old beachfront high-rise, the Ocean Vista. Every year they rented the same suite, 509. In every room hung paintings of lighthouses and old-timey airplanes viewed from below. The ceilings were stained, and although it had been years since smoking was allowed inside the hotel, every room smelled like old cigarettes, just like all the rooms of their house in Chester, South Carolina, and all their clothes always smelled like old cigarettes.

The year she was fifteen Sissy decided that the ocean in April was too cold to swim in, and she sat on the lumpy blanket under the parasol and listened to her mother saw away at her father. Where did he want to go to dinner? Had he heard anything yet about the county HVAC contract? Was he upset about something? And it seemed to Sissy strange, but typical, that they’d sit here with their backs to the world, watching the water like they were waiting for something to come out of it, or for it to change somehow, when it hadn’t changed for millions of years. Her little brothers, the twins Randall and Jeff, frolicked together in the choppy gray waves. They were the only swimmers, the only life you could see in the whole noisy mess. Once, when she was a little girl here, she had asked her mother what was on the other side, and her mother had told her, “If I had to guess, I’d say France,” and Sissy thought about it: France. She imagined a place so lively and strange that it seemed unlikely it could be out there, directly in front of them.

“Skip, what’s bothering you?” said her mother.

Sissy looked at her father, sunk in his beach chair, hooded in smoke. He looked out ahead so far that if anyone could see what was on the other side, he could. He winced when her mother pecked at him, and Sissy got why. Sometimes her mother’s voice was like a snore you’d been listening to all night; just the sound of it made you grind your teeth. And he hated coming here. Being trapped in the car and the hotel and the crummy restaurant booths with four other people, throwing away a year’s savings on a week of lost work. Some of these things Sissy had heard him say, and some things you could just feel, in his silence and in that long gaze. It annoyed her that her mother was blind to it.

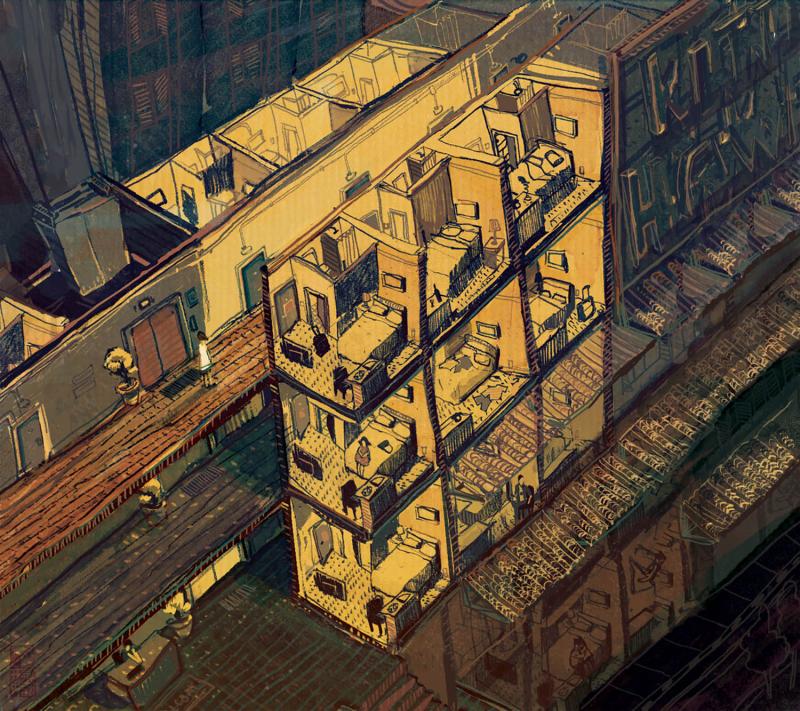

She went back up to the suite alone. She stood in the bathtub and washed the sand from between her toes. She tried to read, and then she watched TV for a while, but she couldn’t sit still. She felt like a bumper car stuck in a corner. So she went out again. She went to the elevator, and rode it to the top, the ninth floor, and came out onto the breezy walkway that looked out across the parking lot and the shops and restaurants along the beach road, which even in the off-season trembled with cars, their roofs flashing in the sun.

But the walkway was quiet, like the halls at school when everyone was in class. She hardly ever saw any other guests here. She put her old-fashioned metal room key into the first door she came to, just to see. It scraped into the slot, but of course the dead bolt wouldn’t turn. She moved on to the next door, and idly twisted the doorknob, and she gave a little gasp as the door fell open.

She peered into the entryway. The air in there was like a held breath. She poked her head in, and the smell of a baking cake surprised her. It seemed to invite her. She bowed in farther. Nothing was moving. Her heart seemed huge in her chest. She set one foot onto the carpet, and when no one leaped out to grab her by the neck, as she was half expecting, she brought her other foot inside. On the wall hung a painting of a pelican standing on a post in front of the blue ocean, its black-pebble eye fixed on Sissy as if it knew more about her than she knew about herself.

She had never imagined that other suites might be different from her family’s. This had only one bedroom, off the entryway, and in the kitchenette the refrigerator was half-sized, as if made for a midget. In the corner of the living area a suitcase lay open, empty, the clothes sprawled in colorful confusion all over the pullout bed, bathing suits and dresses and shirts and underwear, men’s and women’s all tousled up together. On the table sat the cake, yellow with chocolate icing, lopsided like a Dr. Seuss hat. The candles had melted down in puddles bright blue and yellow, and someone had tried to write happy birthday with green icing, the letters jumbled and giddy. The cake had been eaten right out of its pan with pink plastic spoons, which lay around it, alongside beer cans and red cups that breathed out the dizzy smell of liquor.

Inside the refrigerator she discovered a section of sausage pizza and four cans of beer. She took a can from its ring, sat down, and cracked it open. The aluminum vibrated in her palm. She took a gulp. Its coldness spread through her chest. It seemed to slow up everything in her that usually buzzed and jittered. She felt like if the people walked in right now, they would know her. She pinched some cake into her mouth. It was stale, and its faded sweetness made her feel as if she had put inside her some memory of the party that she’d missed. They gathered around her where she stood. They were older than she was but not as old as her parents. They were laughing as they sang.

She drank the rest of the beer and left the empty can on the table, beside the empties that had been there before her.

The next year at school she was a sophomore, and in her theater class she wrote a play. It was about an old man, a bitter, crotchety guy named Filbert, who one day discovers that everyone he speaks to believes everything he tells them. He invents for himself a life history full of adventure and honorable deeds, and by the end everyone around him believes he’s a hero and expects him to behave heroically. She titled it The Good Liar: A play in one act by Cecilia Willard. Her teacher suggested she send the play off to a student contest in Los Angeles, so she did. And each day when she got off the bus, she pulled the mail from the box and flipped through the bills and circulars. But months went by, and one day she forgot to check, and soon after that she stopped expecting to find out anything.

When her family returned in April to Kitty Hawk, she didn’t go down to the beach at all, but right away began to wander the walkways on every floor of the hotel, trying each knob, finding and entering all of the Ocean Vista’s unlocked suites. Every door that fell open to her released a deep, dizzying flush in her body. She riffled around in suitcases, pressed dirty clothes to her face and breathed in their strange smells, and probed with her finger inside little amber medication bottles. She picked up earrings and cell-phone chargers and bottle openers, but in her pockets the keepsakes seemed crude and useless, so instead she took from refrigerators cold drinks and hard-boiled eggs and cookie dough, and although her family, as always, had brought with them tons of Coca-Cola and corn chips and frozen pizzas, standing in the middle of these rooms she ate and drank like a starved orphan. And then, calmed to near sleepiness, filled with all the sensations and possibilities the world had to offer her, she’d stroll out, and let the door sigh shut against her back.

She made herself wait until the end of the week before she rode to the top. And when the elevator doors opened to the ninth floor, they were like stage curtains. She tried the first suite, and the door didn’t budge—she knew it wouldn’t—and she went on to the door of the birthday suite. It was red with gold numbers: 913. In the peephole burned a tiny light, still as a star. The sound of the ocean grew loud in her ears, and a thin queasiness turned in her belly. She put her hand on the knob and it seemed to vibrate in her palm. She gave it a gentle twist, and pressed with her other hand against the door. But it wouldn’t open. And disappointment and relief both flooded into the space inside her that for a year had held the prickly tinsel knot of waiting.

One night in September, her mother tapped on Sissy’s door, came in, sat down on the bed, and halfway into a deep breath began to cry. Sissy, sitting up against her headboard with homework in her lap, froze, as if a bear had come into the room.

“Daddy’s sick,” said her mother. She grabbed on to Sissy’s ankle, and went on crying. “What are we going to do?”

It was lung cancer, and it was aggressive. Her father would never say a word. He started chemotherapy, and for a few months life in their house went on like before, just a little more gingerly. But then he got too sick to work, and things began to unravel. Her father’s employees quit. The work van was repossessed, then the house, and then Sissy and her family moved up to Charlotte, into an apartment. She started a new school, and then her mother was working as a kindergarten teaching assistant, and the twins were working weekends together at a car wash, and Sissy most days after school was working in a coffee shop. She did not keep any of the money she made. When she came home at night, her hair full of the sour smell of the French roast, everyone had gone to their rooms except her father. She’d find him limp in his armchair in front of the TV, alternating drags on his Winston with drags on his oxygen mask. “Hey, Daddy,” she’d say. And he’d turn his head so she could see his bony profile, his eyes watery and gray, his skin like old newspaper. And then she’d say, “Well, good night.”

She was changing. Something bitter and dense was growing inside her. She was tired all the time, and her stomach hurt so badly she couldn’t eat. Her grades began to sink. She was snippy with customers and co-workers and teachers. Although her new classmates seemed to not even notice her, sometimes at school she would lock herself in a bathroom stall for a whole period, just to have the quiet hour alone. And sometimes, lying in bed, she was overtaken by the feverish worry that she was getting sick, too.

At night, her mother came into her room and asked questions about the budget, or about repairing the van, or about presents for the twins’ birthday. And then she’d say, “I wish he would open up to me, Sissy. I just never can tell what’s going on in there.” Her mother’s crying was different now, awful in its restraint, like the visible part of it was only the slightest corner. She wanted to be hugged and reassured, but Sissy couldn’t provide her these things any more than she could fill the checking account with a million dollars.

The weeks wore through to the year’s end. In January her mother said, “He doesn’t have but eight more months, if even that.” And then—right after that—she began to talk about saving for Kitty Hawk. “Mama,” said Sissy, “we can’t afford that. Not this year.” And her mother said, “Baby, this year is all there’s going to be. With Daddy, or maybe ever again.” And for the next several weeks, with every shot of espresso she pulled and with every square of tile she mopped, Sissy imagined the sad little fried seafood dinner for which all her work and sacrifice was destined to pay.

In February, she opened the mailbox to gather the bills and found a letter addressed to her, Cecilia Willard, from Sunset Playwrights. The letter was dated a week before, and signed by someone named Paul Brody, who told Sissy he had loved her play, and he would like to pay for her to come out to California in July to attend a month-long playwriting camp. She sat in her room for an hour as the sunlight drained out of the day. The letter felt in her hands like something she had picked up in someone else’s suite at the Ocean Vista. She tried to remember writing the play. Where she had sat in her old bedroom to work. She tried to see the arrangement of her furniture, much of which was now gone. The wallpaper, the windows—the whole memory was dim and broken. She put the letter away in a drawer, beneath her underwear, and a week later checked to see if it was still there, and if it said the same thing. A month in July, it said. It was like a joke. She tore the letter in half, and then tore those pieces in half, and stuffed the whole mess into the kitchen garbage.

When the last week of April came, Sissy and not her father drove the SUV to Kitty Hawk. The twins sat in the middle row, playing video games in their laps, cheerful and clueless. Her father stretched out with his oxygen and his Winstons in the rearmost seat. And in the passenger seat beside Sissy her mother chirped and chattered, read aloud billboards and church signs, and when they had passed through Raleigh and Sissy had not all morning said one word, her mother said, “What’s gotten into you?” And when Sissy didn’t respond, or even for a second take her eyes off the road, her mother put up the same bruised silence with which she had always responded to the silence of Sissy’s father.

The stucco outer walls of the Ocean Vista seemed dingier than she remembered. She dawdled while her family lugged their things into the hotel ahead of her, and when she came dragging her suitcase into the lobby, the first thing she saw—the only thing she saw—was the desk attendant. Sissy had never seen her before. She was older than Sissy by a few years, one of those beach girls, with hair of many shades, browns and blonds and reds, and a tan so deep it was kind of profound. She wore a little golden ring in her nostril, and on a beaded strand close at her throat hung a yin-yang pendant. Her eyes were blue, and when she looked up, Sissy’s face grew warm and she became aware of her own oversized T-shirt, her jeans and clunky sneakers. It wouldn’t have surprised her to find out this girl wore a bikini beneath her clothes at all times. Her nametag read lucinda. She gave Sissy’s mother the receipts to sign, and slid across the counter the old-fashioned metal room keys, each chained to a yellow foam float like a small banana. “Fifth floor,” she said, like this was the family’s first stay here. “Elevator’s right behind you.” Her clueless helpfulness was charming. With her cottony voice and her tangled hair, she seemed as if she’d been roused out of bed.

Lucinda turned her attention to a television behind the counter, and Sissy went after her family to the elevator. She could not pull her eyes from Lucinda until the doors closed between them.

When she got up to the suite, she went straight out to the balcony and shut the glass door. The beach was vacant, stitched up with tall grass and fences, and the water stretched away forever, gray and choppy. Everything was just like it always was, like it had always been. She felt as small as a moth. And after a moment a strange desperation crept up on her, as it always did when she came to the ocean after a long time away—the feeling that the constant commotion of the surf, the waves’ endless tumbling in and sucking away, anxious and careless, might drive her crazy. But then, after only a few moments, the tension faded, and all the noise slid backward into a kind of gray nothingness, and only a wave’s thunder now and then louder than the others would call her attention back to that monotonous mess, and then again it would fade away. The door skidded open behind her. She didn’t turn. It slid shut again, and she heard the clink and the strike of her father’s Zippo lighter, and the first sweet puff of his cigarette drifted in front of her. She breathed it in through her nose and held it inside her. It burned her nostrils and raised tears in her eyes, and she set all the muscles of her face to keep the tears from falling. And behind her, draw by draw, the cigarette burned down to its filter, and each breath of smoke that her father had held in his own wasted lungs passed her face on its way out to the sea and the sky, and she inhaled it, and held it in her, each breath increasingly acrid, and the tears finally slipped away from her control and crept down to her chin. She should say something. Maybe it was because of the weird charge she got from the girl downstairs, Lucinda, but somehow this moment seemed important, like the universe had delivered to her an opportunity—she knew if she said nothing to her father, one day she would look back on this moment and hate herself. But all her life even her hellos had seemed always to exasperate him, to intrude on his space and his silence, and it hurt her to see that she had annoyed him. And if she turned around right now and said, I’m scared, please tell me what’s going to happen, and what I’ll do when you’re gone, how we’ll get by, and how I can help Mama without murdering her, how you did it for so long—if she even just turned around and said, I’m going to miss you, Daddy, and he gave her that same look of irritation, it would tear her in two. So she said nothing. And finally, but sooner than she expected, came the soft grinding of the cigarette butt against the ashtray. The door slid open and closed behind her, and she was alone again with the waves.

Everyone else went out to dinner, but she stayed behind. She told her mother her stomach hurt, the first words she’d spoken all day. And when they were gone, she went inside and took the spare room key from the table. In the elevator she stared at the buttons. The thought of breaking into someone’s room just to poke around in some dirty clothes made her tired. She rode instead down to the lobby. At the desk, Lucinda sat on a stool so high that the torn knees of her blue jeans were visible above the counter: The sight of her gave Sissy a jolt of adrenaline. Her television murmured sitcom laughter, bland and rhythmic. She glanced up at Sissy and then returned to her program. At the rack full of tourist brochures, Sissy lifted from their slots flyers advertising amusement parks and museums and golf courses. She opened a brochure and without looking at Lucinda she said, “You ever been hang gliding?”

“Nope,” said Lucinda.

“What about this?” said Sissy. “Helicopter tour of seventeenth-century shipwreck sites.”

“I’m scared of heights,” said Lucinda. “Most of that stuff is closed till next month.”

Sissy put her hands into her back pockets and walked on her toes toward the desk. She asked Lucinda if she lived here all year long. Every time Lucinda spoke, she first pointed her eyes upward, like she was listening for some voice to tell her what to say. She said she had an apartment. Sissy asked how much it cost. “Five-fifty,” said Lucinda. “But it’s furnished. Plus utilities are included.”

“In Charlotte,” said Sissy, “we pay ten-fifty for a three-bedroom. It’s highway robbery.”

“It’s not so bad if you can split the rent,” said Lucinda.

“True,” said Sissy.

“My boyfriend is supposed to pay half. In theory.”

“That’s a pretty bracelet.” Sissy touched it, and then put her hand back into her pocket. The bracelet was a broad band of glass beads, green and yellow. Her fingertip tingled.

“My friend Candy makes them on a bead loom,” said Lucinda, and turned up her wrist to show the copper clasp, tiny, delicate, the skin beneath it soft and creamy. “She’s a serious artist. Candy Sinclair. She has a shop in Duck.” Sissy asked what else she was afraid of, besides heights. Lucinda looked upward for a long moment. Her eyelids were dark and sleepy-looking. “Gators, I guess,” she said. “I never seen one except at the zoo, but supposedly we get them here. I think about them whenever I’m in parking lots.”

“I don’t like snakes,” said Sissy. “I’ve never seen a gator.”

“Horses scare me sometimes,” said Lucinda.

“You’re not scared of horses,” said Sissy. “Come on.”

“Them wild horses? Up in Corolla? Me and Scott used to go up there, up past the houses. We’d lay up on the dunes and drink. But I could never just relax and enjoy it, I was so scared those damn horses were going to jump up over the dunes and trample us to death.” She laughed, and her laugh was raspy and deep. Her arms were so tanned and her eyes were the blue-green of a swimming pool’s deep end lit up at night. All her depths seemed visible to Sissy.

Sissy said, “Sometimes when I’m lying in bed at night, I convince myself I’ve got about twelve different kinds of cancer. I can’t even go to sleep. I just want to crawl out of my skin.”

Lucinda said, “I saw your dad’s oxygen tank.”

“Yeah,” said Sissy.

“My aunt had emphysema, till she died. I thought that’s what he might have.”

“Lung cancer,” said Sissy. She was pleased that Lucinda had noticed her, but her pleasure mixed up with a queasy kind of guilt, and also anxiety that Lucinda might think she was fishing for pity. “He brought it on himself,” she said. She had never thought this before, at least not in these words. “He smokes three packs a day.”

“I mean, I smoke,” said Lucinda. “But I wouldn’t say I’m trying to give myself cancer.”

“True,” said Sissy. Her face grew hot. She wasn’t sure what she thought. She said, “What’s it like to live at the beach?”

“I guess it’s like living anywhere,” said Lucinda. “It’s not that different from Greenville. I just get up and go to work, and then I go home and make dinner and smoke up and watch movies. I don’t usually get to pick the movie, but even that I don’t fight with him about it anymore.”

“It sounds nice,” said Sissy.

“I used to be more scared than anything that I’d never get out of Greenville. That’s all I wanted to do, every minute. I’d pray to God, just get me out of Greenville.”

“And you did it,” said Sissy. “You made it.”

“Yeah, I guess,” said Lucinda, and went back to her television program.

The next afternoon Sissy’s family went down to the beach, and she watched from the balcony as they claimed a spot of sand and set up the yellow parasol and their blankets and chairs. Her father collapsed into his seat like a cluster of tent poles. Her mother slipped off her beach robe, and underneath she had on her black one-piece. She’d always been a larger woman, but she’d put on a lot more just in the last year, and it was difficult now to look at her, in that same sad bathing suit, with its ruffled skirt that didn’t hide her waistline like it was meant to, but instead seemed to make fun of it. When she sat down in her chair, Sissy was glad not to have to look at her anymore. She watched them staring out across the ocean. She knew now that Morocco, and not France, lay straight across. The idea of it—Morocco—made her anxious, somehow. She couldn’t even imagine the place. But she could kind of see, now, why someone would want to sit down there, on the beach, and just look at the water. How it could maybe be comforting, to look at something so big and undeniable that hadn’t changed in millions of years. How even when you had to go home, it could comfort you to think that the ocean would still be there whenever you came back. That next year, or fifty years from now, at least one fucking thing in the world would still be the same.

The twins dropped their things on the sand and ran splashing into the waves. At thirteen they were still too dopey to care that the water was cold. She’d always been a little jealous of them. They’d always have each other in a way she’d never be close to anyone. But even for them, the day would come when one would die before the other—it took her breath away to think it. It made her dizzy. She went inside, and just stood there in the middle of the room and breathed, until her vision cleared, and the sound of the ocean had faded again behind her.

She took the key from the kitchen counter and left the suite. She thought of Lucinda. Whatever Lucinda thought of her life, it was a better life than anything in front of Sissy. She felt in it an echo of the possibilities that used to seem to wait behind every door here. She went to the elevator. She rode the elevator, rattling around her like a cage about to come apart, to the ninth floor. She went to the first door, 914. She put her key into the lock, and turned it, and it did not open. She went on to room 913. Now that she stood before it, she felt its pull again. Its red door. Its gold numbers. The steady star in its peephole. The sound of the ocean like something heavy swinging above her head. The cool copper doorknob in her palm: She twisted it, tenderly. She pressed the door. It opened to her.

For many months she had imagined a particular scene. She would enter the birthday suite. Again she would find the cake, and the beer, and the pizza. And again she would take the beer from the fridge, and sit down alone, and drink it. And then the people whose room it was would return, and she would have in common with them that first time she had come here, when she had seen the remains of their party. It was a story she could tell them, and charm them, make them laugh, and they would let her stay.

It was a childish fantasy, and she didn’t really believe it would come true, but to imagine it had made her happy.

Now when she came into the entryway, the first thing she looked for, the pelican on the old wooden post, its tiny knowing eye, she did not find. It had been replaced by a pastel painting of a lighthouse with red stripes. The air in the suite hung ripe with the smell of beer and dirty clothes. In the living area she drew back the vertical blinds from the glass door to get some light into the room. And when she turned to face the mess in the suite, for an instant she was confused—because just as she’d begun to accept, truly, how silly it had been for her to dream that she would ever find here the same people whose cake and beer she had tasted, she found again the pullout bed strewn with clothes, and again she saw the empty cans and cups and scabby paper plates crowding the little table. She looked into the refrigerator, and there lay a pizza—beef and onions this time—and although it was Pabst instead of Budweiser, and bottles instead of cans, there on the shelf waited three beers in a carton.

She took one and opened it. She swallowed a large sip. It was foamy and sour, but it went down smoothly, and she sipped again. She went to the bed and with her finger and thumb lifted a rumpled pair of boxer shorts, light blue with red pinstripes, and she turned them in front of her face, and then dropped them, and picked up an undershirt and, after hesitating only a moment, pressed it against her face and breathed in its tang of cigarette smoke and a faint musk—the smell, she understood, of a man’s body. And just as she saw that all the clothes scattered around her were men’s clothes, the door of the suite opened and then slammed shut.

She tossed the shirt away from her. And she turned from the bed, quickly enough to realize that she was already half-drunk. The two young men who had entered saw her, and froze. One was lanky, with a beard and long brown hair from which hung, over his shoulder, a black-and-white feather. The other, in front, carried by its handle a guitar case, and in his other hand a crumpled Hardee’s bag. He was stocky, with jet-black hair that fell across his eyeglasses. He stared at Sissy. The glasses made his eyes seem huge and unblinking. He turned to look behind him at the one with the long hair and the feather, who made a face as if to say, “Don’t ask me.” Then the one with the glasses turned back to Sissy, and bent at the knees to set down his guitar case, and said, “All right. I’ll go first. Who the fuck are you?”

“I’m sorry,” said Sissy. “I’m in the wrong room.”

“Well, that depends on a couple of things.”

“No, this is definitely the wrong room,” she said. “But the door was unlocked, and I guess I was confused.”

“But you went ahead and made yourself at home.” The one with the glasses pointed at the beer in her hand, and then turned his palm up. “So? What the fuck.” The one with the feather passed behind him. He knelt and began to load beer into the fridge. He said, “Are you hungry?” And when she didn’t answer, he turned to look at her. “There’s pizza,” he said.

“No, not really,” said Sissy.

The one with the glasses turned a chair to face her, and sat and opened the guitar case at his feet. “So are you a burglar? You don’t look like a meth addict. Are you some kind of beach bum? Do they have those this far north?”

“No, I told you. I’m staying in this hotel. I’m just in the wrong—”

“Well I don’t believe you,” he said, and cocked his head, as if daring her to disagree. From the bag he pulled out a sandwich, which he unwrapped and began to eat. His sleeves were rolled into tight cuffs, and inside his forearm was tattooed some kind of geometric design.

“I’m a playwright,” she said.

The one with the glasses snorted, but the one with the beard and the feather said, “Seriously?”

“I just like to look around. I like to see what other people have in their rooms. To get ideas, for dramatic situations.”

“Well then, nicely done,” said the one with the glasses. “I think we have ourselves one of those.”

“You want a beer?” said the one with the feather.

“She’s fucking got one already,” said the one with the glasses. And then his face softened a little, and he said, “It’s fine. Drink it. It’s already open.” And when Sissy didn’t move, he scowled again and said, “Well don’t fucking waste it. If you don’t want it, hand it here.” She stepped toward him. She tried to hold with the muscles of her face, like a slipping mask, an attitude of fearlessness, even nihilism. She held out the bottle. He said, “Drink it. It’s yours now.”

Standing closer to them, she felt, strangely, less uncomfortable. She sipped from the beer. It was thicker, warmer now and yeasty on her tongue. The one with the feather stood up. He was tall and thin. He opened a bottle and said, “I’m Peter.”

“I’m Cecilia,” she said.

“That’s Vaughn,” said Peter. “He’s in a shit-ass mood because we’re out of money, and he can’t get anyone around here to pay us to play.”

“What kind of music do you guys do?”

“Musicians hate that question,” said Vaughn. “You know the Flat Duo Jets? Dex Romweber?” When Sissy shook her head, Peter said, “The Violent Femmes. You know them.” And when she shook her head again, Vaughn said, “Well, Taylor Swift, right? Yeah, we sound just like her.”

“I should go,” said Sissy. “Thank you for the beer.”

“Where are you from?” said Peter. He sat down. They both faced her in their chairs, as though considering her at an audition. She said she was from Charlotte, and Vaughn said, “What kind of plays do you write?”

“Playwrights hate that question,” she said.

“Yes, correct, but then you give points of reference anyway,” said Vaughn. “Because you want people to admire you for your influences. You say Mamet. Sam Shepard. August Wilson.”

“Are you in theater?” said Sissy, and she caught her mask as it slipped, caught the pitch of her voice rising.

“Have you ever actually produced anything?” said Vaughn.

“I won a national contest,” she said.

“I thought Charlotte was more a wrestling and racing kind of town.”

“It has a very vibrant theater community,” she said. “Where are you guys from?”

“My brother’s a stage actor,” said Vaughn, “in case you’re impressed by coincidences. It’s true, though. Right, Peter? He’s up in New York.”

“New York,” said Sissy. She tried to tune her inflection to come across as impressed, but not naïve, and certainly not awestruck.

“Yeah, it’s got a very vibrant theater community,” said Vaughn. “Actually, he’s a graphic designer more of the time than he’s an actor.” He took a small bite of his sandwich and said, “He’s in an off-Broadway company. Or off-off-Broadway, I guess is what they say.” He pushed his glasses up on his nose, and the unguardedness of the gesture relaxed her a little more. He said, “It’s some queer theater. They actually just won some queer theater award. It’s a whole big queer deal. If you’re going to linger, you might as well sit down.” With the sole of his boot he pushed out the one empty chair. Sissy perched on its edge. Vaughn said, “What are you, twelve? Am I going to jail for letting you steal my beer?”

“I’m nineteen,” she said. “I won’t tell. What’s your band called?”

“Peter and Vaughn,” said Vaughn.

Peter wiggled his fingers in the air in front of him and said, “It came to him in a dream.”

“That’s a stage bit,” said Vaughn. “Pete plays the drums, so he entertains the crowd while I’m tuning up.” He lifted from its case his acoustic guitar and held it by the neck. “You lose their attention for ten seconds, and you have to win them all over again.”

“That’s a pretty guitar,” said Sissy. “Are you going to play me something?”

“No,” said Vaughn, and laid the instrument flat across his lap as if to spank it.

Peter leaned his chair back and with one hand opened the fridge, and when he leaned forward again, he offered Sissy a beer. She took it. He said, “I have a dramatic situation for you.”

“All right,” she said, and drank a long gulp. The fresh beer tingled in her mouth. She thought of the word effervescent, and laughed a little to herself.

“So last week we were at this Shoney’s down in Myrtle. We’re at the breakfast bar, and there’s this whole fucking group made up entirely, I do not kid, of one-armed people. I mean, old people and little kids and black people and white people and Chinese people—this international one-armed brigade, all lined up to get their French-toast sticks.”

“They weren’t even all one-armed on the same side,” said Vaughn. “It was chaos.”

“But they were making their way,” said Peter. “They had found each other in the world, and they all went to the breakfast bar together. That’s a play with a happy ending.”

“It might be hard to find twenty one-armed actors,” said Sissy.

“There are ways to fake it,” said Vaughn. “They can do all kinds of shit in the theater these days.”

“Fuck,” said Peter. “Now I want pancakes.”

“I can make pancakes,” said Sissy. “I can make all kinds of breakfast. French toast. Waffles.”

“Stop it,” said Peter. “You’re killing me.”

She laughed and nearly fell out of her chair, for the world was now weighted to her right, like a car taking a long curve too quickly. Vaughn held in his hand a small canteen—yes, it was a Boy Scout canteen, which made Sissy laugh again—and from it he poured liquor into a red cup. He said, “Well this is almost a party. You know who we should get up here? That goddamn girl that works downstairs. She’s kind of a bitch, but goddamn, she’s cute.”

“Lucinda,” said Sissy, and the name glowed on her tongue. “Lucinda. I know her. She has a boyfriend.”

“Well I don’t want to buy a house in the suburbs with her,” said Vaughn. “I just want her to get drunk with us.”

“She likes to get high,” said Sissy. “I do know that about her.” She drank and said, “Do you want me to go see if she’ll come up?”

“Aw, don’t leave,” said Peter. But Vaughn lifted and turned his cup in front of his glasses, like a goblet, like a stage prop, and said, “Cecilia, if you get that girl to come up here, so help me Jesus I will take your play to New York myself and put it directly into the hands … of someone in New York. A producer. I don’t know. We’ll ask my brother.”

Sissy was on her feet, and the floor tilted beneath her, and she grabbed the table to steady herself. Peter said, “Whoa there, sailor,” and she saluted him, and stepped slowly, carefully, toward the door. Out on the walkway, the sun, half-sunk behind the dunes, blinded her, and she gripped the railing and the parking lot checkered with car roofs colorful as gumballs accordioned away from her. She sucked in a deep breath, and the air was clean and fresh inside her. She glided to the elevator. Its doors shut her in with their gentle bumping sound, and she shut her eyes, and the deep darkness spun sideways, as if she were on the inside of a rolling globe, and she sank back against the railing. She would never have this day again. She would never again see the birthday suite. And next year another family would take her suite, her family’s suite, 509, or maybe it would just sit empty. She opened her eyes. And with the flat of her thumb she mashed the button for the lobby, and the car lurched beneath her.

She found Lucinda slouched on her stool, head propped in one hand, those swimming-pool eyes narrowing as Sissy approached. “Lucinda,” she said, and the word melted in her mouth like chocolate icing. “Lucinda, Lucinda. Even your name.” Tears stung her eyes, which was ridiculous, and she laughed a little, and she couldn’t see Lucinda through the tears, which kept coming. “There’s these guys upstairs,” she said. “And we all want you to come up and have some drinks with us.” She cupped her hand beside her mouth and whispered, “I’m pretty sure they’ll get you high.”

“Jesus, honey,” said Lucinda. “Are you okay?”

“We all just want you to come up,” said Sissy, and dragged the back of her hand across her eyes. “I want you to come. Please come up.”

“Honey, I’m working,” said Lucinda, and the way she kept calling her “honey” made Lucinda seem much older, and very loving, and it made Sissy feel very young and small and safe and cared for, as if none of the last terrible year had happened, and the tears filled her eyes again. Lucinda said, “Plus, look at you. You should go back to your room, honey. Your brothers were down here looking for you.”

“I can’t go back there now,” said Sissy. “When do you get off? We want you upstairs. It’s room 913. Do you know which room I mean? They’re musicians.”

“Jesus,” said Lucinda. “All right. Yes. I know exactly who you mean.” She got up and opened a door behind her and peered into it. She said, “Look, you’re gonna get me in trouble. I get off at three, all right? That’s an hour. I want you to go drink some water, and I’ll come up in a little while. Okay?”

“Really?” said Sissy.

“I’ll try to come up for a minute.”

“Promise,” said Sissy. “Nine-thirteen.”

“Yes. God. I promise. But you—no more drinking. Not until I get there. All right? Can you promise me?”

“I can,” said Sissy. “And I do. I never told you my name. I’m Cecilia. Everyone calls me Sissy. But you call me Cecilia.” She held out her hand, and Lucinda held out her hand, and Sissy took Lucinda’s fingers in hers and leaned in close, and kissed the top of Lucinda’s smooth brown wrist. Her hand at Sissy’s face smelled like cigarettes and suntan oil.

“God. All right, honey,” said Lucinda, and pulled away. “You gotta get out of here.”

Sissy was nearly weightless with happiness. She backed away. The smell of Lucinda’s skin stuck to her face. And with her thumb one more time she mashed the button with the arrow pointing upward, and it awakened in light, and she watched the numbers illuminate above the twin doors one by one as toward her the elevator fell: 3, and then 2, and then L.