Keller Introduces Himself: 1953

Keller Introduces Himself: 1953

The golden age of animation came to an end slowly for Adam Keller. Once, for a film called Fantasia, Keller had created lovely images: lava flows boiling over rocks, jellyfish pulsing through a primordial sea. But presently his studio was working on a picture about two dogs: a rich little cocker and a dark-eyed mutt. It was a love story, with animals who talked and performed musical numbers. Keller didn’t much care for the material, but he liked how the story came to an end. The mutt, finally transformed, moved into his girlfriend’s house and lived with her family. Keller liked it for reasons he didn’t fully understand. The mark of a good ending, he believed, was that it affected you in ways you couldn’t easily put into words.

At social events, when Keller said that he was an animator, people usually thought of a man seated at a desk, drawing an endless procession of ducks, but Keller worked in Effects. He drew rivers and rainstorms, waves washing ashore. He animated everything but the characters themselves. Keller rarely explained his job clearly when introduced to people. This, according to his wife, made him look like an ass.

Once, while leaving a charity dinner, she told him, “That’s just the thing with you, Keller.” She’d called him Keller since the days of their courtship. The biblical name “Adam” didn’t fit: Keller wasn’t so much a new man as he was old. “These people,” Eleanor continued, “when you don’t tell them much about your life, they get the feeling you don’t like them.”

Keller looked back at the ballroom where a six-piece band launched into “Roll Out the Barrel.” Grown men were jerking around as though the dance floor were electrified. “These people here?” he said. “I just met them. How should I know if I like them?”

“Tell me this. How long does it take to know if you like a person?”

Keller considered the question. He had four, maybe five good friends in Burbank. He probably had two more from his boyhood, but they still lived in Oregon. He couldn’t see the point in these large social events. All of these fellows pumping his hand, then asking what he did for a living. Keller had worked at the studio for seventeen years. He liked animation, the satisfaction it gave him. He liked the feel of a pencil in his hand, a river or a cloud slowly appearing on the page. But that wasn’t something he could explain in a sentence or two. Eleanor’s question nonetheless intrigued him. He’d never considered friendships in terms of mathematics. “Two years,” he finally pronounced. “As best I can tell, it takes two years to know if you like a person.”

His wife, exasperated, tucked her pocketbook firmly up under her elbow. They were in the middle of a parking lot, surrounded by cars that looked vaguely like the one they owned. “Do you want to know something, Keller?” She stopped walking and waited until she had his full attention. “There are days I don’t know why I married you.”

On the drive home, they were quiet, with the radio tuned to chamber music. They lived in a neighborhood filled with four-bedroom homes. The fellows around here were mostly studio employees, the types whose names rarely appeared on screen. Keller’s own house was quiet. His two older children—both boys—had moved out years ago, leaving only his daughter, Clair, who had just graduated from high school.

Once the car was parked, Keller sat there, looking at his house a good long time. He was surprised how vacant the windows appeared. It occurred to him then that it would be a good idea to leave on a few lights so as to discourage burglars. He thought he might also bolt shut the front windows. It was then that he noticed movement inside his house. Through the front glass he observed shadows shifting across the dining-room wall. One of these forms, no doubt, belonged to his daughter, the other most likely to a boy named Tyler Fitzgerald.

Keller believed that he could be liberal with Clair, as she’d proven herself trustworthy. She’d received high marks on her report cards and was always home before curfew. There was no reason to worry, he told himself. He was acquainted with the Fitzgerald family and felt they were good people. Tyler’s father worked as a gaffer on the Warner lot, where he specialized in stunt sequences and horror films. Still Keller felt his fingers tighten around the steering wheel. He watched the shadows slide toward the back door where, presumably, Tyler jumped the fence and continued on home.

Eleanor saw it, too, and remained quiet. They waited five minutes until they observed Clair framed behind the kitchen window, standing alone at the sink. She washed two dinner plates, which lessened Keller’s concern. The kids, it appeared, had only been having a snack. Keller turned to his wife, noting that she was no longer angry with him. “Come on,” he said. “Let’s go inside. I’ll make you tea.”

“I suppose I could use a cup of tea. That sounds like a good idea right now.”

Keller and Clair

For the first month of summer, Keller let his daughter sunbathe in the backyard and lie about the family room as though she were still a student and would return to school in the fall. For a girl, she was very serious. She understood people easily and liked to read books. Once or twice a week, she ventured over to the Warner lot, where Tyler worked with his father. Though Tyler didn’t have a union card, his father had somehow managed to employ him as a technician. He worked on one of the big stages, where he was quickly absorbing the language of gaffing.

As for Clair herself, four days a week she worked at a bakery, but with high school behind her, Keller thought she might be more productive with her time, especially since she was so bright. Keller felt she would do well in a typing pool or perhaps as the secretary to a low-level manager. But each time he considered the topic, he reminded himself that she was only seventeen. Perhaps the appropriate time to explore her options would be in the fall, after her eighteenth birthday.

Without doubt, Clair was his favorite child. At her core was a streak of loyalty: She kept the same friends for years. In this way, she reminded Keller of himself. His wife had told him many times that it was not proper to favor one child over the others, but now that the boys were living elsewhere, he didn’t see what harm it could do to treat Clair with a little extra fondness and leniency.

Each Christmas, when the children were young, Keller and Eleanor had bought them the same number of gifts. They’d counted them scrupulously and added up the total dollar value spent on each child. But it was apparent that the boys—Christopher and James—were Eleanor’s children. They sought their mother whenever they were upset or injured. Initially Clair, the youngest, divided her attentions evenly between parents. One night she sat next to her mother on the sofa, the following night next to her father as though she were deciding which parent she preferred.

When Clair was four, she wandered into her parents’ bedroom, most likely upset by a dream. Keller, an insomniac, saw her stagger to Eleanor’s side of the bed, where she looked at her mother. Keller observed a wave of thought pass over Clair’s face before she stepped away from the blankets and proceeded to the side where Keller pretended to sleep. Keller went through a pantomime of waking and focusing his gaze. “Dada,” she whispered, “can I sleep with you tonight?”

“Of course,” Keller said, then hooked his arm around the little girl and hoisted her into bed. For hours he expected his daughter to push over to Eleanor’s side, just as his sons had done, but much to his surprise, Clair stayed beside him, with her head resting at the edge of his pillow.

In the years that followed, Keller did his best to teach his children the importance of work. When the boys were old enough, he took them to the studio and escorted them through the various departments. They visited the machine shop, where they admired the giant lathe. They went to the camera department, then they pushed on to editing, where they examined the machinery and screens situated in individual bays. Though Keller knew very little about film editing, he did his best to explain the process: the special cement used to splice together a negative and the odd contraptions that were operated mainly by foot pedals. “That way your hands are free,” Keller speculated.

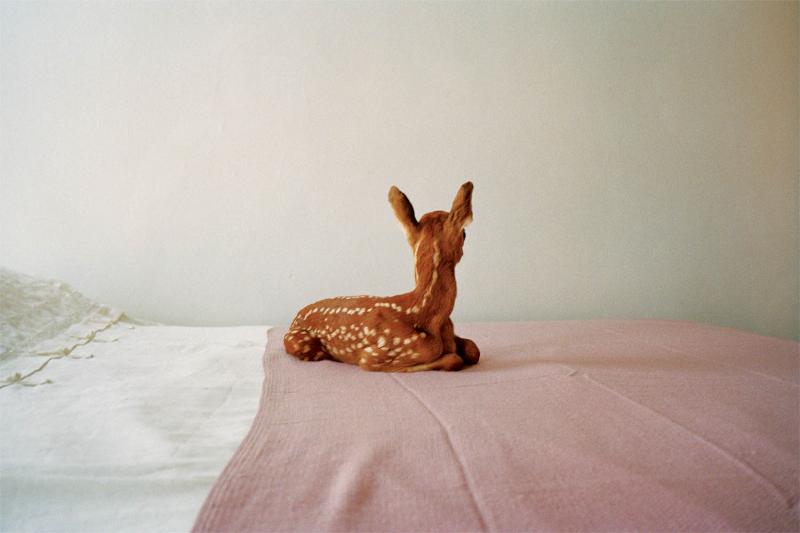

In the animation building, he set the boys down beside his own desk with pride. He was working on a film called Bambi, the story of a young deer in the woods. For weeks, Keller had been animating raindrops as they gusted from the sky. In this movie there was an entire song about raindrops—a song that would require thousands and thousands of water drawings. As he believed the rain sequence not particularly interesting, he’d stacked his board with a scene he’d completed months ago, a scene that featured autumn leaves dropping from a tree. He loved nature drawings, the difficulty of them, and had spent considerable time imagining how these leaves would rotate as they fell to the ground.

After turning on the overhead lights, he lifted the scene off its pegs and handed it to his boys. They’d seen many drawings completed by their father and now looked at these with polite interest. At first they were quiet, but then they understood what was expected of them. Christopher, the older one, picked a page out of the middle. It was a key drawing, one Keller had marked with a timing chart for the benefit of his assistant. “How do you know what order they all go in?” he asked.

“That’s a good question,” Keller began. “All the pages are numbered. See there, up in the corner. And besides, you can observe the line of motion.”

“Oh,” Christopher said, stuffing the drawing back into the stack. Then he held out the scene to his brother who sat beside him, fingers tucked protectively under his thighs.

Without looking at a single drawing, James asked, “Did you draw these all this morning?”

“No,” Keller explained. “That scene there took me three days. I studied special pictures, called photostats. I made a few practice drawings then drew the scene you have there.”

“Three days,” James began. “Our teacher says that you can drive all the way to Canada in three days.”

“I suppose you can,” Keller agreed. “But quality can’t be rushed.” Keller waited for his sons to ask another question, but the boys sat silently. From their facial expressions, a visitor might think them respectful and proud, but Keller suspected that was not the case. When they started to fidget, he decided it was best to take them to the commissary for lunch then drive them home.

Years later, after the boys were in junior high, Keller took Clair to the studio with the intention of showing her the work women did. By then, Keller felt unusually close to his daughter. He liked to hear her voice on the phone and see her freshly washed face peeking up at him from the table as he entered the house for dinner. He planned to take her to three departments, including Ink and Paint, which was casually called the Nunnery and filled mostly with women. But first he took her to his own office. He wanted her to see the place on an actual workday as she’d only been to the studio a few times, always on a weekend. He said hello to Marilyn, the department secretary, then waved a greeting to his boss, a crusty old goat named Mallory.

After closing the office door, Keller showed Clair his desk. His board held a set of drawings he’d started the previous day: It was a harbor scene. More aptly, it was a series of small waves. The studio was making a picture called Little Toot about a group of tugboats. Almost every scene required some water effects. Keller handed the scene to his daughter and was surprised how earnestly she examined the pages.

“You like to draw,” she said, “don’t you?”

“Well, I do enjoy my work,” he explained. “It gives me satisfaction. I like that it’s difficult.”

She lifted curious eyes. “I thought you were good at drawing,” she said. “I didn’t know you found it hard.”

“I suppose I do have a knack for it,” he said, taking a seat beside her. “It’s the movement that’s difficult.” He looked down at his scene, the small waves he’d roughed out on paper. He was still working with these drawings and had not yet cleaned them up into a clear set of construction lines. “Like here,” he continued, “I know how to draw the waves, but it takes me a while to figure out how to move them across the page. That’s the tricky part, you see. Getting the space right between drawings so the movement looks natural.”

“Oh,” she said. She moved two more pages into a discard pile she’d made on a chair beside her. With her index finger, she traced the top curve on a single wave. “Can you teach me how to draw the ocean?” she asked.

For the rest of the day, he stayed in the office with Clair, ordering out to the commissary for cheese sandwiches and milk shakes. He showed her the correct way to hold a pencil. He explained as best he could how to analyze a water image so as to identify its strongest lines. “This is a difficult thing to do,” he said, “because the lines need to suggest depth. And they also need to track motion.”

Together they sat at his lightboard and took turns drawing waves on animation paper. He’d never explained to anyone exactly how he animated a scene. At most, people just wanted to know how to draw Mickey Mouse. By the end of the day, he’d done absolutely no work. He had also failed to show his daughter the Nunnery or even the room occupied by switchboard operators. At five o’clock he left his office, only to find Mallory, his boss, at the end of the corridor, his wiry eyebrows lowered with disapproval.

“Don’t worry,” Keller grumbled. “I’ll work a full shift Saturday and catch up on my scenes.”

“Sounds splendid,” Mallory replied. Then bowing so that his gaze fell on Clair, he touched the girl on the shoulder. “It was a delight to meet you, little lady.”

From then on, whenever Keller took his family to the theater, he would spend time afterward talking with Clair about any sections of animation that appeared in the program. They would talk about the cartoon or little animated sequences that appeared in the short subject. If they saw an animated feature—which was a rare occurrence—they could spend hours picking apart the movie, scene by scene. Clair could identify which effects were realistic and which were drawn with comic exaggeration. She understood that different styles were designed to pull different emotions from an audience. Intuitively she knew when an effects sequence worked and when it did not.

Keller found these conversations an utter delight. For years now, after watching an animated short with his wife, she’d told him, “That was all very impressive, Keller.” But Eleanor’s attention never extended beyond an overall reaction to a cartoon. Clair, on the other hand, was interested in the individual components, how the picture was put together.

In return for his daughter’s affection, Keller made a point of involving himself in the things that interested her. When she turned ten, Keller arranged horseback lessons for his two youngest children. He would’ve paid for Christopher as well, but the boy had taken a summer job at a grocery store. Each Saturday, Keller drove the children to Griffith Park, where they saddled up alongside an instructor. Clair, by nature, was interested in the horse: Was the horse happy, was the horse well fed, did the horse like her? James wanted to know how fast his horse could go and did it once belong to a real cowboy? The instructor took the children on well-defined trails into the foothills. After a month, James grew bored and opted to play with friends once he understood that the lessons would not include lassoing and gunplay.

For the rest of the summer Keller drove Clair alone to the stables. Clair saddled up the same quarter horse every week. She rode this magnificent animal on trails then into a lunging ring where it cantered and jumped over a short fence. Keller usually sat on a bench and read the paper. There were moments when, sitting atop her horse, Clair turned his way, her eyes filled with gratitude. It was in these moments that Keller wondered if the real purpose in marriage wasn’t so much to find a mate but to have children.

On the last day of summer, Keller brought a sketch pad with him to the stable. It had been a long time since he’d worked with the human form, but he wanted a drawing of his daughter on the horse. Most people, he assumed, remembered their lives through photographs. But for Keller, memory was most strongly associated with drawing. Whenever he saw one of his own sketches, he could remember the smallest details that surrounded its creation. He started light and loose, using large shapes to define the horse and also Clair’s body, then he focused in on more precise lines. The final image showed Clair atop her horse, trotting over empty ground. The musculature of the animal, Keller noticed, was slightly off. And the lines of Clair’s face did not fully express her satisfaction. But in Keller’s estimation, it was still a fair effort.

When he showed it to Clair, she studied the image for a long time. He could tell that she liked it. With her gloved finger, she touched the empty portions. “You should add a tree,” she said. “Maybe some grass. Those are the things you draw best.”

Keller knew that she was right. While she unsaddled her horse, he removed a pencil. He found it easy to add grass, a pair of old oaks as well. His hand knew how to create these objects. It was strange how these plants, when drawn well, minimized the flaws in the horse and in his representation of Clair. It was then he remembered something he’d learned a long time ago: Effects, when done right, granted a higher level of believability to the entire film. If trees swayed like trees, if water flowed like water, an audience would happily buy into the reality of the picture, even if it included animals that talked and people who lived under the sea. When Keller showed the revised drawing to his daughter, she smiled as though the image were now perfect.

Though Keller didn’t realize it at the time, he would later conclude that those years were the best of his life. For a while he hoped that Eleanor would join in with Clair as she discussed animation. He thought, too, the boys might take an interest in the studio. But these things never happened. Somewhere around Clair’s thirteenth birthday, he felt his daughter begin to pull away from him. He realized, of course, this was the natural order of things. At first the changes were small. Clair joined 4-H, where she raised lambs at a local farm. Clair went to the movies with her friends more often than with her family. Then came football games, ice-cream socials, and finally boys.

There were times, of course, when Clair accompanied Keller to a picture show. Also, she went out of her way to introduce each of her dates. Keller met Steven Rogers, then Simon Barnes, and finally Tyler Fitzgerald, who became her steady. But the closeness Keller once enjoyed with his daughter—that little world they inhabited together—was largely gone.

Keller didn’t mind Tyler so much. He was a thin boy with pleasant, thoughtful eyes, the type of kid who hadn’t yet experienced any heartache or trouble. One Saturday, while Keller was reading the news, Tyler walked into the family room and took a chair beside him. Keller was aware of the boy’s presence. He was also aware that the boy was waiting for him to put down the paper.

Keller was polite by nature, so he folded the news into his lap and waited for the boy to talk. But oddly the boy just sat there, looking at him with anxious eyes. Keller knew that, at the other end of the house, Clair was dressing for the evening. He also knew that this was the fifth or sixth date she’d entertained with this same young man.

At last the boy unfolded his hands and settled stiffly into a chair. “There’s something I want to tell you,” Tyler began.

“Yes.”

“Well, I’ve watched your films,” he said. “And I think they’re all very good.” The boy shifted how he sat, moving his weight from one side of the chair to the other. “I mean, they’re a lot better than most of the things I’ve seen.”

The statement took Keller by surprise. In the first place, he never thought of the films as his. In the second, no one had ever gone out of their way to review his work.

“I don’t mean I watched them when I was a kid,” the boy continued. “I watched them recently. They have prints over at Warner’s.” The boy nodded his head and folded his hands into his lap as though he were now finished.

“You realize,” Keller said, “that many, many people worked on those pictures. My contributions were small.”

“Of course,” Tyler replied. “But Clair told me which scenes were yours.”

Keller was not sure what to say. He felt slightly embarrassed, so he was grateful when his daughter appeared for her date. She looked at her father with expectant eyes as though she had arranged this meeting. “I’m ready to go out,” she announced. “Do I look dreamy?”

“Yes,” Keller said. “You do.”

“I think so, too,” Tyler said.

As was his habit, Keller followed his daughter to the door. He stood there as she stepped into the boy’s car, which was a Hudson sedan. A sensible car, Keller noted. The sedan glided down the street, becoming small, and turned finally onto another road. Only then did Keller realize he was not alone. Eleanor stood beside him. “He’s a nice boy,” she said.

“I suppose,” Keller grumbled.

“I think he’s nicer than the other boys that come by.”

A cool evening air moved down around them. Keller was about to go inside, but then noticed a softness in his wife’s eyes, a softness he had not observed in a long while. “Senior year is a busy time for a girl,” she said. “Once school is over her time will free up a bit.”

“I was very busy after high school.”

Eleanor touched Keller’s hand. “It’s different for girls,” she said.

For days Keller thought about this, that some of the closeness he’d felt with Clair might return. But when he considered the lives his sons now lived, he suspected this was not the case. They returned each year for the holidays, but aside from that, they rarely drove down to Burbank. James lived in San Francisco where he sold ads for a radio station, and Christopher worked as a hotel gardener in Santa Barbara.

Keller was surprised, therefore, when Clair spent entire days at home after graduating from high school. She still worked at the bakery four afternoons a week, still met Tyler over at Warner’s from time to time. But these activities were not nearly enough to fill her days.

Keller thought he might help his daughter find a full-time job. It was wasteful, he believed, to spend so much time lying around. Had Clair been a boy, he would’ve insisted that he find work. But Keller could not do this with Clair. The truth was: He liked having her at home.

One night when Eleanor was out with the ladies, Keller stood in the kitchen warming a leftover pot of stew. Keller never minded leftovers, but he didn’t want to stay at home all night watching Jack Benny or some other nonsense on TV. He found Clair in the living room, reading a book. In that objective part of his mind, he knew that his daughter was now mostly grown. But to Keller, she looked young—a taller, thinner version of that girl who once rode a quarter horse at the stables. “I was thinking maybe I’d take in a movie,” he began, “and I was wondering if you were interested.”

Keller could see that she was about to turn down his invitation, but then stopped herself. She closed the book in her lap, and her expression warmed. “What’s playing?”

Only then did Keller realize that he had no idea what shows were in town. Seating himself on the couch, he opened the paper. There were two theaters close to their house. One presented a movie that had “0uter space” in the title; the other, a film about a robot. These were movies much like those made by Tyler’s father. Not long ago, there had been such a thing as an “A” feature and a “B” feature. The “A” feature would draw in an audience, and the “B” feature would fill out the program. In the past year, however, studios had pumped money into those pulpy “B” pictures to make them the main attraction. All over town Keller saw advertisements for monster films and pictures about space travel. Tonight he thought maybe he should see one of these shows. But after closer inspection, he noticed that neither listing included a cartoon. The observation depressed him. “Perhaps we should go next week,” he said.

She lifted her eyes. “Why next week?”

He turned the paper so she could read it.

“Oh,” she said. “I see.”

Keller in Effects

The studio where Keller worked was an informal company, one where employees were known by their first names. For this reason, Keller should have been called Adam, except for an unusual coincidence. When he was hired, many years ago, there was already a studio animator named Keller—Keller O’Brien, who worked as a cleanup artist on the Mickey Mouse shorts. When Keller introduced himself as Keller, no one thought much of it. Keller, himself, had never met anyone whose first name was Keller, but as he preferred that name to Adam, he saw this as a bit of luck.

In those early years, when Keller worked as an effects inbetweener, he was known around the lot as “Keller in Effects” while Keller O’Brien was simply Keller. Overall Keller felt fortunate to find himself in Effects, where he could use many skills he’d developed while studying landscape painting in art school. He was also glad because the men in Effects were generally a serious and well-directed lot. A few of them took time off each year to work on paintings of their own. But with three children, Keller could not afford such a luxury.

Keller worked as an inbetweener for six months, then spent a year as an assistant, before his boss, Mallory, recognized his gift of breaking a moving body of water into a series of well-defined lines. From that point forward Keller was a lead animator who drew—or at least supervised—most every water scene animated at the studio. But even when his title rose above that of O’Brien, he was still known as “Keller in Effects.” The main reason for this, Keller told himself, was that O’Brien had worked at the studio eight months longer than he had. It was simply a matter of seniority. But perhaps there were other reasons, ones that Keller did not like to consider too often. O’Brien was a joker, having once dropped water balloons onto studio accountants. O’Brien was a drinker, once reprimanded for keeping a bottle of whiskey under his desk. O’Brien was a ladies’ man, having escorted at least seven Ink and Paint girls on dates.

It was only years later—long after Keller O’Brien died in a drunken car wreck—that “Keller in Effects” became simply “Keller,” with people greeting him at the gate each morning: “Hey there, Keller!” “Whatcha doing, Keller!” “We need those drawings, Keller!” After a few months of this, it was as though he had owned the name all along.

Keller Asks a Question

For the rest of the summer, on Thursday nights, Keller resumed his old habit of seeing a movie each week with his wife and Clair. Though Keller never considered himself a traditional family man, he still liked driving into town with Eleanor at his side and his daughter stretched out in the backseat. The movies now were not full programs. The short subjects had gone away, as had the newsreels. But Keller did his best to find a sensible film, one with a little animation before it. He was not particularly fond of the Bugs Bunny reels with their loopy caricatures and smear drawings, but he didn’t so much mind the Mr. Magoo shorts. He admired their experimental style, which he likened to a children’s storybook brought to life.

When the program let out, Keller took Eleanor and Clair to a soda shop in Toluca Lake, which was one of the places his family had frequented years ago. Once the floats were ordered, Keller most always started in on a few things he’d noticed while watching the cartoon. Clair was happy to talk about animation and the main feature as well. But without the boys to occupy Eleanor, Keller felt guilty repeatedly guiding the conversation back to those things that interested him. He could tell that Clair felt the same, so he allowed the conversation to slide toward topics his wife enjoyed, such as movie stars and any scenes that had caused her eyes to go misty.

In the third week of August, Keller took his family to The Newswriter, which was about a journalist who spent his time tracking big stories. At the peak of his career, during the war, he exposed German sympathizers trying to steal American military secrets from a base in Canada. For this, the journalist was awarded a medal for distinguished civilian service. Keller sensed the picture should have ended there, on that high note, but instead it followed the journalist for seven more years, as he struggled to break another big story. The newswriter eventually left his family and took a room in Washington, DC, where he spent his final days chasing congressmen and eating meals alone.

The ending didn’t upset Keller so much as it confused him. He knew that this ending would probably prove unpopular with many audiences and therefore limit the money the picture could make, and yet, as he watched the final scene, he was oddly drawn to it. It was unbelievably sad, the way the writer sat in a dining booth looking out the window at passing cars. He had never seen a movie portray this type of desperation. He believed that Eleanor and Clair would find the story—or at least its ending—engrossing, but when the houselights brightened, he found expressions of bored disinterest on each of their faces.

In the car, as he pulled out of the parking lot, his wife said, “The movie could’ve used a little more romance.”

“I suppose so,” Keller replied. “But I don’t think that fellow was much interested in romance.”

“Maybe so. But I always like romance in a picture. It gives a person hope.”

From the back seat, Clair said, “I agree. The film needed something to balance its mood. The second half was too depressing.”

“At least that man broke one big story,” Eleanor offered. “He exposed those German spies.”

“Sympathizers,” Keller corrected. “They were sympathizers.”

“Yes, sympathizers,” his wife agreed.

“But the ending,” Keller said. “I still think it was right for the film.”

“Maybe it was,” she replied.

That night they did not go out as they all claimed they were tired. The movie was longer than they had expected, and the night was unusually warm. Fifteen minutes later, Keller was in his bedroom changing into his nightclothes. Since the age of fifteen, he’d performed stretches before bedtime. He rotated his arms in large circles, first one way then the other. He lifted his knees perpendicular to his waist. But tonight he did not complete his routine. Instead he walked to the bathroom where he found his wife at the sink applying night cream to her face. “Eleanor,” he said, “I want you to tell me something.” He stood there a moment, not sure what to say. There was a question inside him—a sense of dissatisfaction in his chest—but he couldn’t find the right words to express it. “Do you think we have a happy life?”

His wife, surprised, turned to him slowly, still holding the jar of night cream. “Why, yes,” she said. “You have a very good job. You work for the movies. How many people from art school still draw for a living?”

“Not many,” he admitted.

“We have a fine house,” she continued. “And fine children. Besides, we have each other.”

As Keller thought about this, he began to feel better. He took a bicarbonate to settle his stomach then reclined into bed. His wife was right, he decided. He had no reason to feel dissatisfied. He was not like that newswriter in the movie. He was successful at work, even if his work was presently a little dull.

Keller Breaks a Rule

As a general rule, Keller did not see a movie more than once. His reasoning on this was sound: Why pay for something you had already experienced? There were times, however, that he broke this rule. For example, he had seen the animated version of Gulliver’s Travels many times. The shipwreck sequence, in particular, fascinated him—waves breaking onto the deck, how they separated into water and foam. But rarely did he see a live-action picture a second time, not even Sunset Boulevard, which he considered a masterpiece.

After watching The Newswriter, though, he found himself thinking about the film’s lead character in a way that surprised him. He thought about the movie while he drove to work and even while he stacked paper onto his pegboard. He felt he understood the newswriter better than he understood most members of his family. One evening, when he knew that his wife and daughter would be out, he drove to the theater alone. He told himself he was simply going to look at the lobby cards, but once there, he could find no good reason not to pay the fifty cents and see the film again. He suspected that the picture might bore him when viewed a second time. Much to his surprise he was mesmerized.

The actor who played the newswriter was quite accomplished. Even though the film never explored the character’s background, Keller believed he understood a few things that likely had happened to the newswriter when he was young: He’d been a small boy, Keller figured, often teased at school, a boy whom teachers rarely called on during class. Through the character’s facial expressions and bodily gestures, Keller could sense how essential it was to this journalist to break important stories.

Keller wasn’t a person who deceived himself. He knew that he, too, had once felt like this. As a young man, he’d burned to create something new, to animate the natural world so that the images were as compelling as any landscape displayed in a gallery. He believed his work in Bambi and Fantasia was very good. Maybe it wasn’t the work of a master. It was, however, his personal best, and other animators admired it.

As the movie came to an end, Keller once again found the final scene incredibly sad, the man sitting at a restaurant booth, an empty pad of paper before him. Keller blinked twice then allowed his chest to expand deeply with air. Keller wondered why he found this movie so much sadder than other pictures, particularly those about the war.

As the room brightened, Keller rose and brushed crumbs from his jacket. The theater was more crowded than he remembered. He was about to leave when he saw a young man raise a hand toward him in greeting. The hand, he discovered, belonged to Tyler Fitzgerald, who sat beside his father.

Keller did not feel like being social, but he was not one to be rude. He buttoned his jacket. He blinked once more then walked up the aisle to meet them. Max Fitzgerald had made a name for himself on musicals but now worked primarily on horror and science-fiction films. “Keller, my man,” Max began. “I’ve been meaning to send a note your way. The studio has me on an island picture. The setup for each shot takes forever. We’re going to be sixteen weeks before it’s done.”

“An island picture?” asked Keller.

“You know, an island picture with a creature in it,” Max continued. “It’s really quite complex. A tentacled beast that comes up out of the sea.”

“I’ve heard these pictures are quite something now,” Keller said.

“I wouldn’t say that. This picture here, The Newswriter, now that was something.”

“It was,” Keller agreed. “The production was excellent.”

Max turned to his son, offering him an expression that Keller couldn’t quite read, then his eyes lifted. “Our kids are spending a lot of time together. I hear that Tyler has taken a few meals at your place.”

“Your son is always welcome.”

“I appreciate that. I really do,” Max said. At this point, he put his hand on Keller’s shoulder and left it there. The gesture made Keller slightly uncomfortable, but he realized it was meant with kindness. “You work in effects, right?”

“I do,” Keller said.

“I was thinking that you might come to the studio. We have a stage wired for a big scene. There’s a tank, a wave machine, lights all over the place. Tyler’s working the carbon rods.”

“The carbon rods?” Keller asked.

“You know, for lightning. The creature walks out of the sea during a storm.” Only then did Max finally remove his hand. “We’re doing a technical rehearsal in a couple days. I’d like to get your thoughts.”

Tyler stepped forward. “You should come, Mr. Keller. We’ve worked on it for weeks.”

Keller exhaled in a way that even to him seemed a little rude. “I’ll see what I can do,” he said.

“Afterward dinner is on me,” Max promised. “Any place you like.”

Keller Beyond Effects

Keller had no interest in attending a technical rehearsal for a monster movie—even for one with a budget large enough to afford the use of an indoor water tank. But he recognized a conspiratorial chumminess in Max Fitzgerald’s demeanor that suggested his son’s interest in Clair might be serious. Keller understood that, at some point, he would need to make room for a son-in-law. At the studio, he’d seen other men push their daughters away when a serious suitor entered the picture. This was the last thing Keller wanted, which was the primary reason he’d allowed Clair to entertain Tyler at their house without supervision.

At the breakfast table the following morning, Keller waited for Clair to appear. Though he could easily critique a young animator’s work, he did not always know how to begin an important conversation with his daughter. He wanted to know her intentions with Tyler Fitzgerald. Moreover, he wanted to know if Tyler had ever discussed his intentions with her. Around eight o’clock, Clair emerged from her room, a bathrobe cocooned around her body, a single row of curlers at the back of her hair. Keller waited for her to collect a piece of toast and pour some juice before clearing his throat to indicate that he had something important to say. “So did you and Mother have a good time last night?”

“Mother always enjoys a ladies card game.”

“And I take it the two of you won?”

“We won our share,” Clair said.

She sat opposite her father. Usually she was relaxed and casual at breakfast, but today, she placed her elbows stiffly on the table. She took two bites then pushed the toast away. She looked distractedly through the paper then lifted her eyes to her father. Keller braced himself for the coming conversation. He would need to praise Tyler’s best qualities, perhaps noting that the boy had a sensitive streak. But before he could proceed, his daughter placed her hand atop his. “I know I should have a regular job, Daddy,” she said. “I plan to apply for one next week. I don’t want you to be disappointed in me.”

“Well that’s all very good,” he said. “But I was hoping to talk to you about another matter. Last night I ran into Max Fitzgerald. Actually, I ran into Tyler, too. They were together.”

“You went to the movies?” she said. Then Keller observed a look of recognition pass over her face. “You saw the same movie, Daddy? The one about the journalist?”

“I did see that movie again,” Keller confessed. “But that’s not the point. As I was talking to Max Fitzgerald, he invited me over to the Warner lot. He apparently is staging a big scene.”

Clair leaned in toward her father, and her expression softened. “It’s simply amazing,” she said. “The stage is filled with water, except for the part that’s an island.”

“Yes. I gathered that. Supposedly there’s a monster as well.”

“You wouldn’t believe it, Daddy. The monster’s a guy in a suit. A sea creature poisoned with radiation. But there’s about fifteen guys up in the rafters who control its tentacles. It’s all very realistic.”

“I’m sure it is,” Keller said. He folded his hands before him and considered ways that he could maneuver this conversation back to the subject of Tyler’s intentions. Before his mind alighted on the right words, he felt his daughter tap him once on the arm. “I’m glad he asked you, Daddy. I was hoping he would.”

“You knew about this?”

“You’ll be so impressed. You’ll go, won’t you?”

“Something was mentioned about a technical rehearsal.”

“In a couple days,” Clair responded. “Thursday afternoon.”

Keller sat there, looking at his daughter. Her face expressed both excitement as well as some other emotion Keller didn’t know how to read. “I suppose I can fit it into my schedule,” he said.

“I’m so happy,” she said again. “I told Tyler’s dad that you were really good at laying out scenes. I thought you might have some ideas.”

Keller dismissed this suggestion with a nod of his head. “I’m sure they have it all planned out.”

As Keller drove to work, he realized that he had not only committed himself to witnessing the technical rehearsal for a monster movie, he had somehow agreed to lay out a few shots. Years ago, when the films at his studio had been more effects-heavy, he had laid out a few scenes. He had done that in Fantasia, Bambi as well, but that was a long time ago. Keller understood enough about production to know that Max Fitzgerald, as a gaffer, would oversee a good deal of the set. The line of command would fall from the unit director to the DP to the gaffer, who for a movie like this would help frame the shots and might even discuss camera positions. But why would anyone on the set care what he, as an animator, had to say about anything?

For a while, Keller felt better. He enjoyed his drive, the wide street relatively empty with no cars getting in his way. By the time he arrived at the studio, he found himself irritated once again, as he realized what this technical rehearsal would involve. Keller would need to make small talk with cameramen and technicians. He would also need to say a few gracious things about the set, perhaps even the creature. It would be best, Keller thought, if he worked up one or two compliments beforehand.

He parked his car in his usual spot and started off toward the animation building. Long ago, he’d looked forward to his work each day. He’d admired the single-mindedness of his studio, that every building somehow supported animation. But in recent years the Disney brothers had rented out a soundstage for TV production. Toward the back, the brothers were constructing another stage, one large enough for live-action features.

Once inside the Effects corridor, Keller offered a customary greeting to Marilyn, the department secretary, then slumped into his office. On his pegboard were drawings he’d started the previous day, a set that would not take more than a few hours to finish. Another animator had sent over three scenes, each in its own folder, in which a dog ran through a stream. The canine animation was complete. Keller would only animate the water the dog displaced with every step.

In the old days, Keller would’ve examined each movement, considering the dog’s weight and speed in relationship to the stream. But now he simply closed his eyes and saw the water move. For most of the morning, he worked at his desk, rolling the pages back and forth to check the action. These were small, simple drawings—accents, really. They made the dog’s movement appear more realistic, but generally, the water animation would be lost on screen. If done right, no one would notice it.

Toward lunch, he was beginning to find his rhythm. He completed three scenes—the dog, from different angles, moving through water—when he observed that his door was partially open. Standing there he found Marilyn, wearing a blue-striped dress, a notepad in her hand. “You have a message, Keller,” she said.

“Who’s complaining about my work now?”

“Your daughter called, something about a rehearsal being moved up to this afternoon.”

“This afternoon?” he asked. “You mean, today?”

“She sounded excited.” Marilyn looked at the drawings stacked up on the pegboard then at Keller himself. “Is she working at Warner’s now?”

“Her boyfriend is. Sometimes she goes with him. The boy’s father is Max Fitzgerald.”

“Max Fitzgerald,” she repeated. With her arms crossed, she leaned against the doorjamb and considered this. “That’s a big movie they’re making. I’ve heard about it.”

“I’ve heard some as well,” he said.

She straightened up, letting her arms fall at her sides, but she did not leave right away. “How old is Clair?”

“Seventeen,” Keller said.

“Seventeen, that’s an important age for a girl. A lot of things change at seventeen. You know that, don’t you, Keller?”

Keller was about to say, “I do,” but then he recognized an insistence in Marilyn’s demeanor. Her voice was slightly deeper and softer than the one she regularly used with him. For a moment, Keller sat quietly, folding his hands onto his desk then unfolding them. “What time should I be there?” he asked.

The Warner lot was not far, maybe only a couple miles from the studio where Keller worked. As he drove across town, he wondered how his daughter had sounded on the phone. She must have expressed some desperation or exuberance; otherwise, why would Marilyn suggest so strongly that Keller find time for this rehearsal?

More than anything Keller did not want his daughter to move to a new town, as had his sons. Nor did he want her to create a new life for herself, one in which he did not have an important role. He could feel it then: the importance of this day. He would need to make space for Tyler Fitzgerald inside his family, a space large enough perhaps for Tyler’s parents as well. But Keller wasn’t good at creating these types of spaces. He wished Eleanor was with him, but there was not enough time to arrange that.

At the Warner gate, a guard pointed Keller to the visitor’s lot and gave him directions to the stage where Max Fitzgerald worked. Each time Keller entered the Warner lot he was surprised how much larger it was than the studio where he worked: soundstage after soundstage, each as big as a football field. There were office buildings and workshops, a row of warehouses for props, two structures reserved for camera equipment and another for the film lab.

Keller was disoriented, as many buildings appeared identical, but then he heard the thrum of large motors and noticed a few puddles outside one stage. The enormous vehicle door had been left open—the kind studiohands called an “elephant door”—so Keller could see deeply into the structure. Three men—one of whom was probably the unit director—stood on a spatula platform suspended out over the water tank. The camera was there, too, housed beneath a small canopy to keep it dry. Most everyone on the set wore a rain slicker.

Keller had visited many stages, but he’d never seen one quite like this. The subterranean tank was massive, like a lagoon in the middle of the building. At the far end were palm trees and sand, a man-made beach sloping down to the water. At the end of the stage were dump tanks and wave makers, fans so large Keller thought the blades might actually be airplane propellers. Then he saw his daughter. Clair was wearing a rain slicker, as was Tyler beside her. The boy stood at some type of control board. His face appeared serious in a way that made him seem older and more self-assured. Keller wanted to like this boy. Keller was about to call out, when the boy spotted him. “Hi there, Mr. Keller,” he said. “We’re about to run some exposure tests.”

With that Clair found him there, standing at the edge of the tank. Her face initially registered surprise but soon deepened into kindness. “I didn’t think you were going to make it,” she said.

“Marilyn thought I should come.”

Clair guided him around the set and pointed out a few things of interest: the beach complete with cabanas and palm trees, the sprinkler lines that would shower down rain, lights covered with ocher jellies to simulate sunset, and the carbon rods that would spark lightning. The set was far more elaborate than anything Keller had imagined. There was something in it he found fascinating, something beyond the fakery and propping he’d witnessed on other sets. It was then he realized that the job Clair would apply for—the one she’d mentioned—was probably here, with this production crew and Tyler.

“I’m so glad you came, Daddy. Isn’t it amazing what Mr. Fitzgerald can do?” She nodded toward the camera platform, that wide metal shelf suspended over water, and the men perched up there. “He’s done the lights and everything. He even set up the tank. The director’s out on location.”

“I see,” Keller said.

As the elephant door closed, blocking out sunlight, Clair led her father away from the tank, toward wooden benches at the far end of the stage. The benches were empty, except for a sketch pad. Keller put his hand tentatively on his daughter’s arm. “I was wondering,” Keller began, “if Tyler has ever discussed with you his intentions.”

Clair turned to him, her eyes glistening with interest. “I’m only seventeen,” she said. “I plan to live at home for another year or two.”

“You spend so much time with him,” Keller said. “I just thought—”

“It’s 1953, Daddy. The world’s a different place. I want to take everything slow.”

The work lights began to dim, and the stage filled with the burnt amber of fading sunset. Fans hummed into motion. On the island a suit actor appeared dressed for his role. The creature had six tentacles and walked backward down the beach, into the water, looking for his mark. Directly above, on pin rails, a dozen technicians followed like a dark cloud. They each held support wires that carried the creature’s springy arms.

“They’ll do a few takes today,” Clair said, “try out different lights, different angles. It will all come out in the dailies tomorrow.”

“I know,” Keller replied.

“I need to go over by Tyler,” she said. “For the most part, you’ll be dry here.” She started to walk away, but then turned back. “You know,” she said, “Mr. Fitzgerald was hoping you’d board out a few scenes. He likes new ideas. He thinks you’ll be good at this.”

Keller nodded. He looked down at the sketch pad then folded his hands into his lap.

At the edge of the tank four men worked the wave makers, churning the water into a steady chop. Waterlines let down rain. A johnboat puttered in front of the camera where a man, standing, lifted a clapboard. Then amber lights darkened to embers. Fans torqued with speed. Rain slanted down in sheets. And lightning broke from the ceiling—first from rods positioned in the corner then directly overhead.

The feeling came down around Keller slowly—a prickly sensation, like an icy breeze gusting over his arms and back. He’d not felt this way in years, not since the days of Fantasia. Much to his surprise, he found himself leaning forward, waiting for the creature to rise from the muck. Already he knew how he’d board out this sequence: an establishing shot with the camera gimbaling as though it, too, floated on the surf, then tightening in as water parted and the creature emerged in shadow. Keller knew to show as little as possible: a tentacle, a shoulder, footprints in wet sand.

When he noticed the overhead technicians lift their wires, Keller stood and walked to the tank. The noise from the fans was unbelievable. Stray drops spotted his shirt. Lightning burst over the set, and Keller saw tentacles dance up from the dark water. Lightning broke again, and Keller saw his daughter on the other side of the tank. She stood there, dressed in a rain slicker, but she wasn’t looking at the creature, nor was she looking at Tyler. Instead her gaze was focused on her father, her features set with satisfaction, as though she knew Keller needed something like this—a sense that the world was larger than his animation desk—as she took her first real job, her first boyfriend, and began the slow process of leaving home.