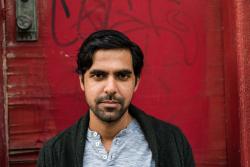

Of all the types of yoga practiced in the US today—Hatha yoga, Ashtanga yoga,Vinyasa yoga, Bikram yoga—the one that I enjoy most happens to be the one that I invented. I like to call this type of yoga “wrong yoga.”

Of all the types of yoga practiced in the US today—Hatha yoga, Ashtanga yoga,Vinyasa yoga, Bikram yoga—the one that I enjoy most happens to be the one that I invented. I like to call this type of yoga “wrong yoga.”

Wrong yoga began one morning on a mat in my apartment on Clinton Avenue, in a burning square of light supplied by my east-facing window. My practice soon moved down to the lawn in front of my building, where I felt I could show off all the wrong moves I had developed to the men and women pouring into the neighborhood for the Saturday flea market.

There are many ways of communicating in New York. One is through the names of Wi-Fi networks. On my block, these included YO!APT202TurnOFFtheKENNY_G, NghbrhdYOGACLOWN, 2PAC&UPaki, and NOCARBS4ME, all of which must have cut high-frequency arcs through my body as I did yoga. Another way of communicating is through the middle finger, which New Yorkers eagerly brandish at any car trying to do basic car things like make a yellow light. And the third and perhaps most ubiquitous form of communication in the city is conversation about yoga.

You will be surprised by how many lonely women—and men—will stop to talk to you if you do wrong yoga in your building’s front yard (the rarity of the front yard itself never to be remarked on). Even the usual laws of yoga conversation don’t explain it. Is it possible that certain women have an urge to correct a wayward yogi the way they have an urge to correct those of us who have unruly personalities? Or is it something simpler: the sight of an individual debasing himself so thoroughly in public attracting curiosity the way an accident attracts gawkers?

As the spring gave way to summer, I began to see that I had acquired a sort of superpower. The more I hurt myself with these obscene postures, the more attention I attracted. Excited by this development, I began to go down to the Zaatar House Middle Eastern restaurant and discuss the matter with the head waiter, Mina.

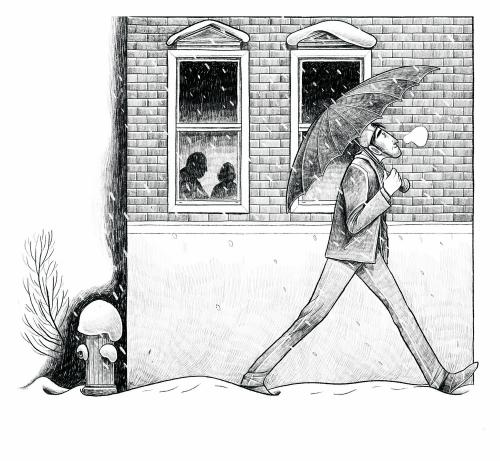

Mina, who was in his late thirties, was an Egyptian, but he had an indeterminate Aryan look about him. He was the leading expert on lonely women in the neighborhood. Whenever I came to the restaurant he served me a vegetable kebab platter and another objectionable story about his conquests. He always left my table to go kiss another one of his svelte customers on the cheek. Mina, I found out later, was a Coptic Christian; he’d emigrated to the US from Egypt because he wanted to coach soccer in schools. Things turned out differently. When he arrived in Queens, he found that being gifted at soccer wasn’t enough to become a coach. You also needed English. He struggled with the language, went at it, punched holes in it, tried to breathe against the gush of his Arabic instincts—I imagined him down in the water in a sack, struggling like Houdini—but it was no use. English evaded him. He could strut around like a cock in his restaurant and flirt with women but he was basically crippled. In the meantime, he searched for work in the Arabic-language schools in Brooklyn. And here, too, like a cruel joke, the same prejudices he must have fled in Egypt asserted themselves. “The Muslim guys don’t want a Christian to coach,” he said in a matter-of-fact way.

Strangely, I didn’t feel bad for him. He was too shifty, too unreliable in his attentions, and when he spoke to me it was always with one eye on a woman in the corner. “He’s happy,” I thought. “He’s mourning soccer because it makes him a tragic figure, but he’s really quite happy.” On my block there was even a Wi-Fi network worshipfully named after him.

Then, one day, long after the Arab Spring had ended, I asked him how things were back home, whether he planned to return. “Maybe, brother,” he said. But his look was vacant, even accusatory, the look of someone who has been caught out. And it occurred to me that, though the Spring was a source of pride in Egypt, it had only reminded this man, stuck in the purgatory of his restaurant, that he was missing out on things back home (though, being a Copt, even that was complicated). And perhaps this has been the source of his exasperation all along—not soccer, not English, not women, but something personal and sad keeping him from Egypt all these years. I disliked myself for not having noticed it before.

Soon after this conversation I fell into a depression. I had seen it coming all spring and summer, had seen it rippling on the whorls in my old windows, had felt it in my tense postures on the grass, and then, just like that, I was in it. I gave up yoga and went back to my room with its crazily sloping floors. I sat before the window in my office chair and thought back to childhood, which is where the mind travels when it is afraid of death.

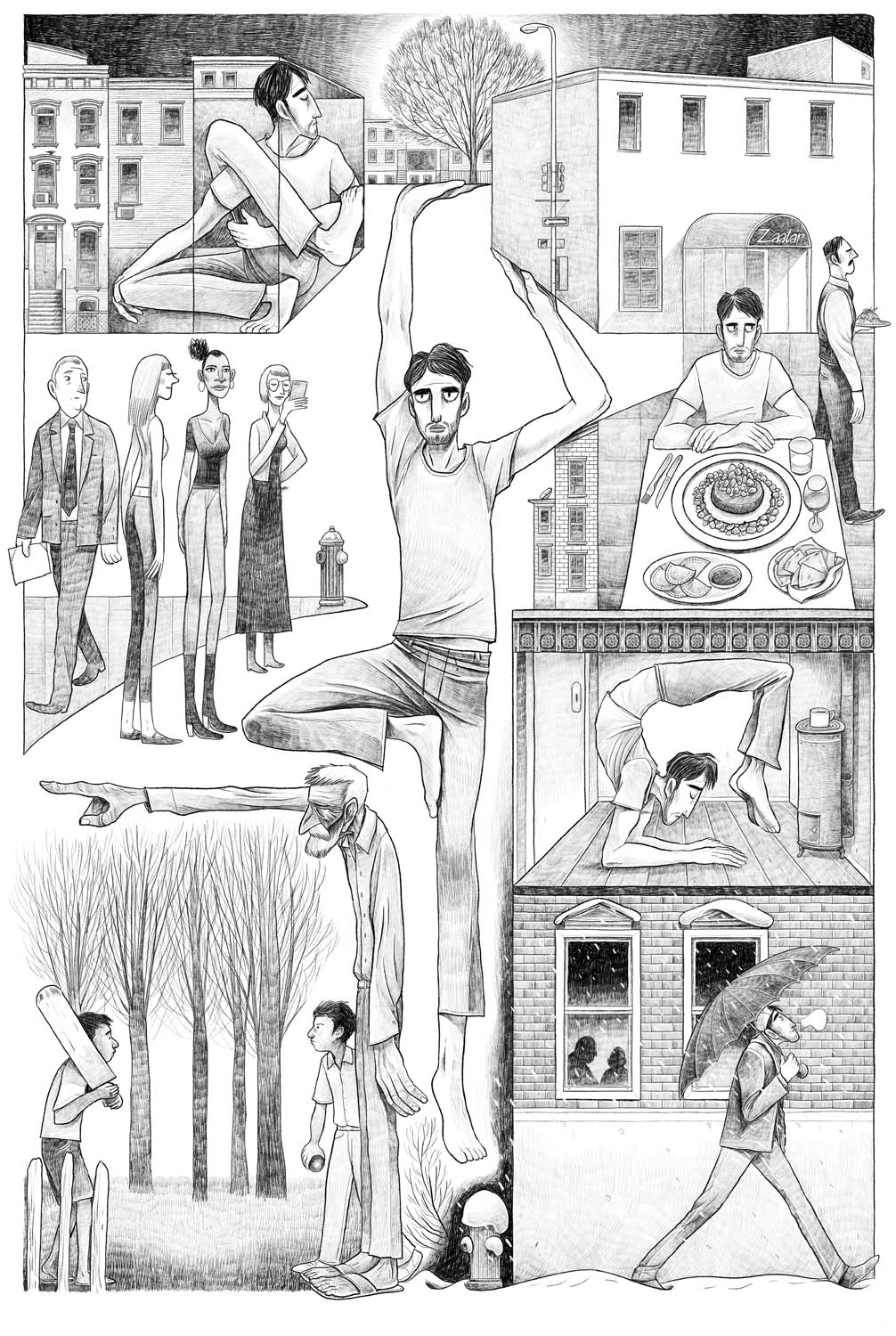

I had been obsessed with cricket as a young man in India. I loved the game but I also cherished the statistics, the equipment, the boredom, the tea. Yet, as I sat at the window, it was not the sport with its pleasant longueurs that came back to me, but rather something else, something more specific, the image of a single boy: Sharad. Sharad, one of the richest people I have ever met, was an awful fellow. Having inserted himself into my ragtag group of teenage cricketers in the neighborhood park, he proceeded to disperse his servants, six of them, among our teams like spies. These servants were nice enough fellows, only a little older than us, but they were terrified of Sharad, and if you got one on your team you could guarantee that he was playing not for you but for his little master.

We put up with Sharad because he supplied us with the equipment—pads and bats and bails—and also because his parents were divorced, and we felt pity for him. But Sharad tested our pity. He cheated and argued about scores. He bowled purposely at our faces and insulted his servants. He ridiculed the weaker players. And then, one day, after a terrible row about a run out (he felt, naturally, that he was not out), he strode out of the park, marched into a side street, and complained to a neighborhood official about our cricketing in the park.

A white-haired man with sucked-in cheeks appeared at the rusted green fence of the park. “Beta, the rules on the plaque say that no cricket or sporting activities are permitted here,” he said. Where had he been all this time? It was technically a “walking” and “strolling” park, one of those places where middle-aged paunchy people fool themselves into thinking that a thirty-minute daily amble will cancel out a lifetime of sedentary sweetmeat-eating.

A white-haired man with sucked-in cheeks appeared at the rusted green fence of the park. “Beta, the rules on the plaque say that no cricket or sporting activities are permitted here,” he said. Where had he been all this time? It was technically a “walking” and “strolling” park, one of those places where middle-aged paunchy people fool themselves into thinking that a thirty-minute daily amble will cancel out a lifetime of sedentary sweetmeat-eating.

We thought the man, one of the neighborhood “uncles,” would disappear into his own laziness, but Sharad must have persisted. We were pushed out. Within days, the bald expanse in the middle of the park, where we dug our wickets, was peppered over with young green grass. Wooden benches with iron legs clogged the grounds. Petunias and phlox began to arrogantly bloom in the empty beds around the walking paths; the paths themselves filled with the sluggish diabetics of our parents’ generation.

All Sharad’s doing! Over a run out!

All these years, I had never forgiven him, but now, sitting in my bed in Brooklyn, I wanted nothing more than to switch places with Sharad, to be cruel like Sharad, to be a person who injured others instead of injuring himself. Outside, fall was ending.

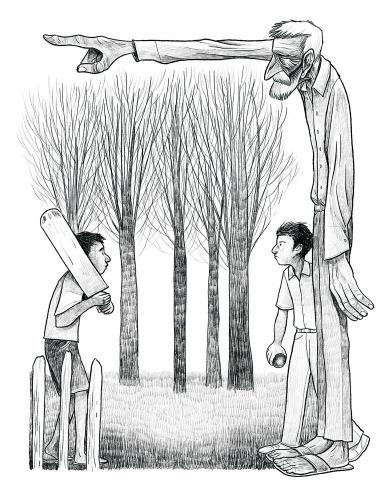

The fall had started with fevers, with people coughing into their sleeves on the subway, with fairs, with couples fighting on the street. Now winter brought its bitterness and cold and toxic metal scents, and I felt again the strange need I always felt—especially when I was depressed—to move. I packed up my things. I ate one last time at the Zaatar House, where Mina refused to talk to me. The patch of lawn where I’d performed wrong yoga was blank with snow.

The new apartment was in Park Slope and had elegant pressed-tin ceilings with floral designs: carnations, I think. When I moved in, the landlady pointed out a niche in the first-floor landing. “When people died in these houses,” she said cheerfully, “the wakes used to be held in the living room. You needed the niche or you couldn’t get the coffin up these narrow stairs.” She directed me to put my stuff in the attic, which was so low I had to crawl. “People used to live there, you know,” she said. I believed it.

Soon after, having stowed away my things, I got my espresso maker going on the stove. After two weeks, I began to feel settled. I brought out my mat. It was then that I discovered that the pressed-tin ceilings of the apartment were too low; too low for right yoga and too low for wrong yoga and I experienced a deep panic. My ex-girlfriends had always said that I made decisions too fast and there was a great deal of truth to that. I’d never lived in an apartment I liked, never thought to examine such things as the water pressure in the shower or the heat in the bedroom when I moved in. When I decided, I just decided.

I was grateful that I was alone so that no one knew that I had screwed up. This is the main benefit of being alone.

But the panic! The panic I experienced that night in the absence of my wrong yoga was frightening. And it was then, breathing through my mouth, that I decided to go out for a walk in the middle of the night.

But the panic! The panic I experienced that night in the absence of my wrong yoga was frightening. And it was then, breathing through my mouth, that I decided to go out for a walk in the middle of the night.

It was moonlit outside, snowing, the city’s million conversations blotted out by the rhythmic exhalation of the falling snow. I put one foot before the other on the pavement. I felt the panic inside me balanced by the cold outside. And I waited, as I took my first steps in this new setting, for something bad to happen, for my foot to slip or my ankle to twist, for something to free me for a moment from myself and make me what I had been when I had come into this world, a happy howling animal.

1 Comments

The transitions are so stunning, so slight-of-hand, one doesn't notice them, but is swept along to another moment, place, filibuster of life, caught between now and then and a new kind of yoga--walking in snow. The drawings leap from the page, give a life to the words which, by themselves, are words. A world created in a few words. Believable. I have met all the people, including the landlady--know them, precise aspects revealed here. Stunning.