Claire was coming over with her boyfriend—her partner—and Joan was baking mince pies in preparation, though she couldn’t remember whether Claire liked mince pies. It was difficult to keep everything straight with four children who changed their preferences every week, but she’d put strawberry jam in some of them instead, because who doesn’t like jam?

They’d heard nothing for six months, then Claire phoned the landline, out of the blue, and asked if they’d be at home tomorrow, because she wanted to come round. The week before Christmas. They’d steeled themselves not to hear from her at all, which was exactly what had happened two Christmases ago, their voicemails ignored, the texts unanswered: a bewildering, unnatural silence that had settled over Joan’s head like one of those hoods you put on falcons, and lasted far into the new year and was never explained.

Henry came in. “That’s the landing light working now. Not that she’s going to notice.”

“It isn’t for her,” Joan said. “It’s for us.”

Joan and Henry ran a bed-and-breakfast out of a house they couldn’t afford, a sprawling seven-bedroom place on the edge of a town once famous for its salty hard cheese and its Sunday market. Three of its rooms were let out every night, usually to traveling businessmen, small-timers who still used a Filofax, whose client base was dying off, and also to older couples on modest holidays—walkers, people Joan needn’t worry about, though occasionally a younger pair came through, professional, sometimes Londoners, in town for a friend’s wedding. These younger couples looked impossibly clean and arrogant. They breezed in and out with matching smirks on their faces; they appreciated the John Lewis salt and pepper grinders at breakfast, the Farrow & Ball paint on the stairs, but she could see them thinking that they’d never end up like this, serving strangers in their own home, running down the clock. They were expecting to live lives in which the end is never in sight until it’s upon you.

Claire had loved these guests when she was little. She’d make a nuisance of herself, bothering the girls about their jewelry, until Joan would have to send her out of the breakfast room on some mission or other. The couples would look knowingly at one another across their poached eggs, basking in Claire’s admiration, flirting with the idea of themselves as mothers and fathers, ones who’d do anything to make their child feel loved. Just you wait, Joan had thought, skimming off the poaching water. Just you wait till you’re settled and the girl’s your own.

She had one of those couples staying at the moment. Two nights. She didn’t think it was a wedding. They had arrived yesterday, after eight o’clock and smelling of wine. They’d driven up in the boyfriend’s car. He was very upright and very slim, with a permanent smile. The girl was one of those executive types: Even now, on a Sunday morning, she’d come down dressed as if she were going to a meeting. Perhaps she was. But these days there was nobody around to admire her silver tennis bracelet, her polished bag. Tessa, Joan’s youngest, was seventeen, so shy that she avoided the breakfast room at all costs, and—as it happened—was still asleep, though it was nearly midday.

Henry was tidying the living room: She could hear him pummeling cushions. Richard, back from university for the holidays, had gone out for a bike ride, and the eldest, Neal, wouldn’t be home for another two days, if he made it at all. Joan allowed herself to believe that he would; she allowed herself to imagine all six of them under the same roof for Christmas that year, and rolled her pastry a fraction thinner. Richard would come back muddy and hungry from his ride, he’d stuff the pies without thinking into his mouth, and she couldn’t begrudge him that. She sealed them with egg wash and put them in the oven, and then she heard tires on the gravel outside.

“Henry?”

“It’s just room two,” he called.

That was the couple, back already. They’d only been gone three hours. It was something the younger ones did, coming and going throughout the day, as if it were a hotel. They disappeared up to their rooms and there might be noises. Joan was not an idiot. She knew people had sex in her house: She was the one who stripped the bedclothes afterward and put them in the wash. It was not a pleasant fact, but it was part of the business she’d chosen to run. It seemed unnecessary, though, for guests to do it in the daytime, then lounge in bed when Joan was up and working. It suggested that they thought of her as a cleaner, an invisible member of their hospitality staff, rather than—as she considered herself—a landlady or proprietress.

“Tessie?” She knocked hard on Tessa’s door, then pushed inside. Sleepy noises greeted her, a stale smell, and something rumbling away on the laptop, rain and thunder, because Tessie claimed she couldn’t sleep without background noise. “Tessie, get up. Your sister’s coming round.”

Normally Tessa would lie and doze, but today she sat up quickly, as if she’d been pulled on a string. “Claire’s coming?”

“What other sister have you got?”

Joan gathered dirty mugs from the shelves and took them back down with her. Science experiments, Henry called them. They were part of the stale smell, the green powders they contained; but not the whole of it. Tessa’s was not a clean shyness. There was something furtive and greasy in it, something Joan didn’t want to know.

Claire was twenty-five; the man standing beside her was clearly past forty. “Mark,” he said, putting out his hand, and Joan recoiled. He looked heavy—not fat, but muscular, broad-shouldered, large-boned, with an oddly narrow, fluted nose. And was that a tattoo snaking down his wrist? Claire appeared delicate beside him. She stood in the middle of the kitchen as though it weren’t hers, as though she’d never seen the place before. It was Mark who looked at ease: a studied kind of looseness, challenging somehow.

“You’ve changed the cupboards,” Claire said. Her voice had a bitter note that Joan immediately remembered.

“Would you like to sit down?”

“We’ve been scrunched in the car for an hour.”

Joan stopped herself from asking where they’d driven from, why it had taken an hour. Last she knew, Claire had been living in a shared house in Radcliffe, but that was ten months ago. It all could’ve changed.

“So, Mark,” Henry ventured, “what is it you do?”

Mark nodded, without surprise, as if he’d been waiting for this question. “I coach people, Henry,” he said.

“Rugby? Boxing?”

“I’m a life coach, actually. So a little bit of fitness, yeah, but it’s more than that.”

Joan could tell that Henry didn’t know what life coaching was. Joan did. She’d thought about trying it herself, and now she was glad she never had. She asked, “Is that how you met?”

“I’m not paying him,” Claire said, instantly, “if that’s what you mean.”

“It was a meetup,” Mark said, and now it was Joan’s turn to be confused. He could see it, and began to smile. He explained that he did a lot of stuff online. People watched, they commented and joined in. He coached online too. (That made sense. Claire had spent thousands of hours online when she lived at home. They’d had to switch the Wi-Fi off to get her to bed.) Sometimes he did a random meetup somewhere, getting face-to-face with the fans. He appeared to say “fans” without irony. Perhaps Joan wasn’t attuned to his tone yet. Or perhaps he was actually famous—what passed for famous these days. Claire came along to one of the meetups, Mark continued. They hit it off straightaway. They went for a drink, didn’t they? The rest is history, he said, though it was news to Joan, and delivered too easily, too directly, without any of the nerves you’d expect from a boyfriend meeting the parents for the first time. That was his age, she supposed. He might be closer to Henry’s than he was to Claire’s.

“And you enjoy it,” Henry asked, “this coaching?”

“I see people transform their lives. What could be better than that?” Mark’s spread hands were casual, but his tone was unappealingly serious. Not that different from Claire’s other boyfriends, then. She’d always gone for men who couldn’t laugh at themselves.

“It’s all about transformations these days, isn’t it?” Joan said. “Makeovers and things. Getting rid of all your possessions. Moving to Australia. Maybe that’s what we need to do. Maybe we need to sell up and move to Australia.”

Claire’s mouth twitched, as if to say maybe you do. Or was Joan imagining that? Normally she could tell when someone was being funny with her. The kids had made a joke of it years ago, how Mum always thought you were being funny with her, or the woman in the shop was, or so-and-so’s friend. But with Claire she had not been able to decide. When would they finally be old enough to see them at last—to see what they’d made—to know them as strangers and think to yourself, yes, we’ve things in common, or no, we’ve nothing at all? When would she know if she liked her daughter?

Henry was asking everyone and no one if they wanted coffee.

“No. Actually—” Claire paused, and Mark touched her arm. It seemed like a supportive gesture, though later Joan would wonder. “I’d like to clear my old stuff out of my room. Have you got some bin bags, please?”

Claire’s old room was Tessa’s room now. They had shared it when they were little, then Tessa had moved down to Neal’s room when Neal left. After Claire left, Tessa had wanted to move back, so they’d put all of Claire’s stuff into the crawl space: The room had a deep crawl space that went right back into the eaves. Claire had made a den of this for her and Tess when they were younger. She’d run string lights into it and put blankets on the floor. It was an eighth room, really, if you didn’t mind crouching all the time. She’d even put a sign on the door, room eight, in wobbly script. Occasionally, she would sleep in there all night, indifferent to the silverfish, the cold.

Claire and Mark spent hours going through the crawl space. Claire stayed upstairs the whole time, sorting through her stuff, while Mark carried the trash bags down and loaded them into his car.

“We can take those,” Joan said, and Henry agreed: He said, “You can leave the rubbish,” but Mark politely insisted that they would be driving past the dump regardless. He had already carried a couple of crates upstairs, which Claire would presumably fill with things she wanted to keep, if she wanted to keep anything at all. Joan watched the procession of black garbage bags, the rising pile in the car’s dropped backseat, and despaired. How could she want so little? Disposing of the Barbies and the ancient birthday cards was one thing, but what about her notes from university, her artwork from GCSE?

Joan remembered the struggle to decide what to keep from her own mother’s house. The glass-bead necklaces, heavy, like strings of marbles. The ugly squadron of Toby jugs. But that had been unavoidable. Her mother had been dead, a stroke at seventy-six—would Claire even remember?—and Joan’s brothers were worse than useless at practical things, so she’d left Henry with the kids and done it herself in one weekend. And those had been her mother’s things, not Joan’s. She wondered for a moment where her own schoolbooks were, and found that she didn’t know. She and Henry had a deep crawl space in their room too, full of old suitcases and curtains too short for this house’s windows and the boxed-up Toby jugs. Perhaps she would look for them later.

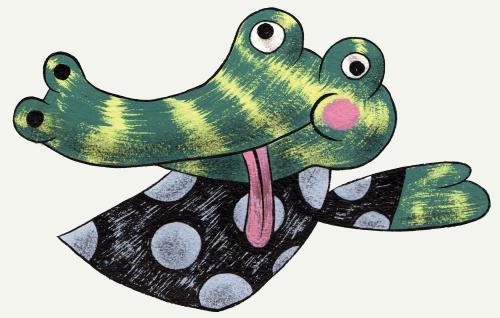

Mark dumped another bag in the car and powered back upstairs. Joan ventured out across the gravel and looked into the open trunk. The bags lay slumped heavily across one another. Their twisted ends wrinkled and breathed. One was untied: She plunged her hand in, a lucky dip, grabbed the spine of something, and pulled it out. Not a schoolbook, not what she was hoping for—something full of Claire’s sweet round handwriting from before she forcibly changed it, at age fourteen, to a spiky mess—but a program: Muster’s Puppets presents…A Journey Round the Moon.

She was amazed. Claire had always maintained that she could not remember going to see this show at the church hall, though Joan had taken her twice, she loved it so much. This had been before Tessa, when Richard was tiny and Neal was away at school. She’d taken Richard in his stroller, and miraculously he’d slept through the whole thing, both times, while Claire had crept forward through the chairs and sat on the dusty floor at the front with other children, with strangers. She hadn’t been frightened of the puppets at all, though they were enormous, with marrow-size heads that split in half when they talked, operated by men and women dressed all in black, with black balaclavas. When they got home, Claire had tried to make a puppet of her own, with pink felt and polystyrene and a piece of dowel; she’d called it Suzanne, and worn her black windbreaker with the hood up and carried it around the house. Suzanne talked in a strangled voice, high in the back of Claire’s throat; it passed comment on what everyone was doing, though its mouth wouldn’t open and close. God, that puppet! Joan had hated it, hated the weird insistence with which Claire reached for it every morning, how she greeted the postman with it—and when she brought it into the breakfast room, where the B&B guests were eating, and made it go from table to table interviewing them about their plans for the day, Joan had marched Claire out of there, Suzanne protesting in its strangled voice, while the guests laughed nervously into their coffee and thought that perhaps they would not stay at Joan’s on their next excursion.

She’d taken Suzanne away, in fact. She’d put it in a black trash bag in the crawl space in her and Henry’s room, and told Claire that she couldn’t have it back for a month—and when the month had passed, Claire didn’t mention it, and neither did Joan.

At last Claire emerged, smudged and tired, and accepted some tea, though not a mince pie. Mark wanted pints of water. They sat at the kitchen table and after a long silence Claire said, “I’m not happy,” as if she had expected to be.

At last Claire emerged, smudged and tired, and accepted some tea, though not a mince pie. Mark wanted pints of water. They sat at the kitchen table and after a long silence Claire said, “I’m not happy,” as if she had expected to be.

“No,” Henry murmured.

“I feel like I’ve felt this way for a long time.”

Joan said, “This is the first I’m hearing about it.”

“It’s not. I’ve tried to tell you.”

“When have you tried?”

“Lots of times.”

“But when?”

“Claire,” Henry said, “you can always talk to us. You know that.”

“I think what Claire’s saying”—this was Mark—“is that she talks, but she isn’t sure you listen.”

“Of course we listen,” Joan said. “When have we not listened?”

“I’ve asked you not to keep forwarding me job adverts,” Claire said.

Claire had been temping at the same accounting firm since she finished her degree. It wasn’t temping anymore, it was a proper secretarial job, just without any of the benefits. She typed up letters, she answered the phone, but it wasn’t what she wanted to do with her life. It couldn’t be. So Joan sent her adverts for graduate jobs from time to time: Where was the harm in that?

“I hardly ever send them,” she said.

“I don’t want you to send them at all. I’ve told you that. I said it three years ago. Why’s it so hard?”

“So just ignore them. Delete them as soon as they arrive.”

“I don’t want to have to see them!”

“Well.” Joan sat back in her chair. “You’ve got a lot to say for yourself today. It’s not so long ago you wouldn’t say anything at all. Does he know about that?”

“He knows everything. He knows me better than you.”

Joan sighed. “It was half a year, Claire. Half a year when you lived in this house and you wouldn’t say a word. That was very difficult for us.”

“But she’s over it now, aren’t you?” Henry said.

“No, Dad, that’s what I’m saying. I’m unhappy. I’m depressed.”

“I’m sorry to hear that,” Joan said. “I know things haven’t been easy for you recently.”

“It’s not just recently. It’s been years.”

“Well, I’m sorry to hear that,” Joan said again. “But depression’s a chemical thing, you know, it’s a chemical imbalance. That’s why antidepressants are so effective.”

“Depression,” Claire said, her voice wavering, “is withheld knowledge.”

“Oh, Claire. You don’t even sound like yourself. Where did you get that from?”

“It’s John Layard,” Mark said.

“Who’s John Layard?”

“A Jungian analyst; a very good one, actually.”

“I don’t know what that’s got to do with anything.”

“I’m telling you,” Claire said. “My depression comes from feeling things and knowing things that I’m not allowed to express.”

“Like what?” Joan asked. “Not allowed by who? By me?” Claire didn’t answer. “Don’t be silly,” Joan said. “You can tell me”—she stopped short of saying anything—“whatever you want.”

“I can tell you what you want to hear.”

“That’s not true. You’ve just told me you’re depressed, and that’s not something I wanted to hear.”

“Isn’t it?”

“Of course it’s not!”

Claire was crying now, though it didn’t stop her from talking. Her accusations became confused: that Joan had never paid attention to her, that Henry just let Joan do everything her way, that they had never taught Claire how to look after herself, that they had allowed her to see one of her teachers when she was still at school. It was amazing to Joan that she could say this with the boyfriend sitting right beside her. But Mark didn’t blink. He said, “Claire and I have ended up together because that’s how her sexuality was formed. She engaged with an older man at a very formative point in her life.”

Her sexuality! Joan nearly laughed. I cleaned up your shit, she wanted to tell her. I cleaned up your shit and your piss and your vomit, I combed the nits out of your hair, I put calamine lotion on your chicken pox blisters, and did I mention the shit? Did I mention the times you shit the bed even though you were basically too old to do something like that, and I had to come in and gather the sheets up around it, this hot stinking little parcel, gather it up and flip it into the toilet, soak the sheets in bleach, put the washer on at three in the morning? How many other people’s bodily fluids have you had to deal with in your life? None. Your cat’s, maybe. You scoop hard, matted cat shit out of a litter box with a plastic spade and you think you understand what it is to be a caregiver.

“We’re not here to lay blame,” Mark said. “We’re just letting you know. Claire needs to take responsibility for her own emotional well-being now. She needs to move on.”

His interventions were smugly authoritative; he seemed to have access to some story about their family that Joan didn’t have, that wasn’t true. What had Claire told him? Joan wanted to shake her, make her admit she’d lied, but she just said, “Taking responsibility for yourself sounds like a good idea.”

“You should do the same,” Mark said.

“Meaning what?”

“Why don’t you think about it for a minute and decide for yourself?”

Oh, this was too much. This man—who was this man? Why did Claire allow him to speak to her mother like that? Was he an abuser? She started to wonder. Was Claire here under some sort of duress? She wouldn’t have assumed that just because of his age, but his behavior was frightening, it made her frightened for her child.

“Claire,” she said, “does he talk this way to you?”

“He’s sticking up for me. He loves me. This is what it looks like.”

Henry, goaded, said, “Your Mum’s done her best.”

“And what’ve you done?” asked Mark.

Joan quite liked him for that. Joan had always been the baddie where Claire was concerned. Now Henry could get a taste of it, and Joan could rush to his defense more firmly than she’d rushed to her own. “Claire, he’s very welcome, but I can’t have him speaking to Henry like that.”

Claire gave an ugly laugh that made the two clear cables of snot hanging from her nose lengthen and sway. “Bully for you,” she said, standing up. “Come on. It’s completely pointless.”

She hobbled out to the car as if she’d just survived a terrible accident, with Mark holding her shoulders. They drove off, and Joan couldn’t even see their silhouettes receding, because the back windshield was entirely blocked by the heap of bags. She and Henry stood there on the gravel for a moment. A blackbird rustled in the hedge. Neither of them spoke. What was there to say? Claire’s behavior, her wild emotion, was so outlandish that once it was over it seemed like a dream.

Turning back to the house, Joan saw movement: the professional couple, standing in the window of room two, staring down as if the private scene had been a form of complimentary entertainment, like the magazines beside their bed.

“Henry,” she said.

He didn’t answer. He was standing with his hands on his hips, looking down at the toes of his shoes.

“Henry.”

“I just need a minute.”

Joan felt a spot of rain on her cheek. The sky had clouded over; she would have to rescue the sheets from the line. They had a regular due that night, a quiet man, Federico, who stayed every week so he could take his mother to St. Margaret’s early on Monday mornings. Something to do with her lipids. Joan gathered the still-damp sheets and took them inside and put them in the tumble dryer. Then she went upstairs and knocked on the door of room two, more loudly than she normally would. There was a scuffling inside. The girl opened the door, in a robe, her hair loose.

“Yes?”

“You have to leave.”

Her expression was amused, appraising. “I don’t think so. I think we’re booked another night.”

“I don’t care what you’re booked. Get your stuff.”

“Is there a problem?”

“I don’t have to explain myself to you,” Joan said. “This is my house and I don’t want either of you in it.”

The girl laughed, a hard, dismayed little laugh, then stopped. “I’m not paying.”

“Not for tonight, no.”

“Not for last night either. Is this how you run your business? It’s pathetic. You wouldn’t last a week in a city.”

“You’ll pay for the night you stayed. I’ll charge your card.”

“Just so you know,” the girl hissed, “your other daughter’s upstairs throwing things. So, you’re a fabulous mother too.”

Joan found Tessa’s bedclothes ripped off; piles of graphic novels knocked over; broken, irreplaceable Victorian tiles on the hearth, but no Tess. The curtains were open. Tessa had a lovely view of the laburnum tree, now bleak and withered like an ancient flay, though in summer its blazing yellow flowers trailed to Earth in long chains that shifted in the breeze, revealing vertical slices of the garden, the field where one horse grazed. The childhood Joan had offered them could not have been more idyllic. But what did it matter: What did it matter with girls? Claire had ridden off on the back of her own mood, she’d taken it with her, she’d spread it wherever she went, and Joan would not be permitted to defend herself.

Joan found Tessa’s bedclothes ripped off; piles of graphic novels knocked over; broken, irreplaceable Victorian tiles on the hearth, but no Tess. The curtains were open. Tessa had a lovely view of the laburnum tree, now bleak and withered like an ancient flay, though in summer its blazing yellow flowers trailed to Earth in long chains that shifted in the breeze, revealing vertical slices of the garden, the field where one horse grazed. The childhood Joan had offered them could not have been more idyllic. But what did it matter: What did it matter with girls? Claire had ridden off on the back of her own mood, she’d taken it with her, she’d spread it wherever she went, and Joan would not be permitted to defend herself.

A sharp tap, close by, made her whirl around, and though she didn’t believe that anything violent was going to happen, she could not later persuade herself that the thought hadn’t entered her mind. Children did, after all, occasionally harm their parents. Christmas was the worst of times for that. But the noise had come from the crawl space. So that was where Tessa was. Joan knelt and saw that the door was slightly open, and that the string lights, incredibly, were still operational, bathing Tessa in a pale glow as she lay on her back, her feet against the wall, the lights looping and swirling within reach above her face, the sloped ceiling receding into the eaves, into darkness.

“Leave me alone,” Tessa said. Her voice was hard, and Joan knew that she must have overheard everything. Tessa had a nasty habit of creeping around the house, listening to conversations that had nothing to do with her. She must have come downstairs while they were all in the kitchen and witnessed Claire’s distress.

Joan crept into the crawl space; she somehow folded her legs underneath her, twisted around, and pulled the door closed. The sense of pleasure was immediate, primal. A cave. The light from each bulb was sharp, but didn’t travel far, and the darkness in the eaves was undisturbed. She could hear her daughter breathing. She wanted to touch her, but knew that Tessa would fight her off. Gently, slowly, she leaned against the door, then felt it click. Felt it hold.

“You didn’t shut it properly?” Tessa said, with disbelief.

“What do you mean?”

“Did you close it all the way?”

“Should I not have done that?”

Tessa rolled over and put her hands flat against the door. It didn’t move. “You’ve locked us in.”

Joan laughed. “I can’t have done.”

“You have. There’s no handle inside.”

The door wouldn’t give, whatever they tried. Tessa was laughing now, but differently, almost cruelly. She didn’t seem to care—she’d brought herself in here, hadn’t she? It was where she wanted to be. But Joan had things to do. Federico would be arriving. The lamb needed its rub.

She called for Henry—feebly at first, then louder, though she couldn’t bring herself to yell full-throat. It seemed ridiculous. She banged on the door, and the banging drowned her voice out, the tone of it, growing more exasperated now, as if this was all Henry’s fault for not listening closely enough. Was he still outside on the gravel? Had he gone to his shed?

“You must have a way to open it,” she said. “You and Claire, you must have had a way.”

But Tessa lay down and closed her eyes.

Joan heard the dim final sound of a car door slamming—the couple leaving, perhaps. Perhaps it had been stupid to evict them. That girl was the sort who’d write terrible reviews on all the websites she could find. But what was the point of owning your own business if not to make things personal once in a while? It was not a power Joan had exercised often, but one she’d been glad to possess. A sort of silent compensation.

She tried to remember what she’d learned about the attic when they first moved in. This had been nineteen years ago, when Claire was five or six. She remembered it had needed insulation, a thick layer of fiberglass fluff the contractors laid down, because there were gaps all over the place, spaces for the house’s warm air to rise into, then escape between the orange tiles. Hadn’t there been some question of obstructing the eaves? The ceiling sloped sharply—the crawl space, the attic, was anvil-shaped—and Joan inched toward the narrow wedge until she felt cold air on her hands. The inside walls of the crawl space didn’t actually meet the external walls of the house. There was space, at the end, to squeeze through, and even to descend, stepping from joist to joist, wriggling down the cavity wall, then—what? Breaking through the plasterboard into the dining room? Making a mess? No, she would not go down. She’d go sideways, toward the other bedroom on the attic floor, which was hers and Henry’s.

The end wall scraped her ribs and cheek as she squirmed past; her head bumped a tile, though it didn’t fall. There was space on the other side, some kind of space, though it wasn’t the other crawl space, it was empty but for yellow insulation and hammocks of spiderwebs and a few spokes of light picking out the disused chimney breast that fed the fireplace in her own room. Nearly there. She crawled across and touched the far wall and found her way to the end.

This time the gap was narrower, and she thought she might not be able to squeeze through at all, and then not be able to squeeze back. She’d be pinned forever. Tess would never tell; they’d never find her. She’d be like one of those mummified pigeon corpses the man had fished out from behind the grate of the gas fire, just a bundle of bones and leathery skin and imperishable jeggings, a cautionary tale for the house’s next owner.

With a last convulsion she was out, though she felt her sleeve tear. She crawled forward. Blocky heaps against the black were the boxes and cases they had piled in there; and strokes of light outlined the crawl space door ahead, which was held with just a latch on the outside, tiny and fragile, she’d break it easily if she pushed, and she did. Daylight burst in, dazzling her. She turned back toward the junk and shouted, “Tessa, it’s all right, I’m through.”

No answer. Little madam. She could wait to be released.

Downstairs there was no sign of Henry. No sign of Richard either. Joan hoped he hadn’t gotten a flat tire. He did that sometimes, got stranded on the moors, and Henry had to drive out and fetch him. Maybe that was where Henry had gone.

She went out of the front door, onto the driveway, and saw that Henry’s car was not there. Neither was the couple’s. Neither was Mark’s. Claire had gone—she was always going, but she always came back. Joan had once picked her up from the bus stop at the end of the road, to which she had dragged her Winnie-the-Pooh suitcase on its wobbly single wheel. She had picked her up from the bus station too, when the man she’d become obsessed with, a former guest at the B&B, had failed to make good on his promise to spirit her away to France. That had been a long drive home, the hate radiating off her, as if Joan had arranged the betrayal herself, not been scrubbing bathrooms all morning, oblivious to her daughter’s absconding from home, from school, until she’d phoned for a lift.

Near the pylon, through the hedge, Joan saw the red flash of a car. Not Henry—his was silver—but Federico, arriving exactly as planned. Joan went inside to put the kettle on. She always made Federico a cup of tea when he arrived; she would sit with him as he drank it, patiently teasing from him whatever would pass for news, before he went to the carvery up the road. Federico was a nervous speaker, his plumpness rather feminine, his fluttering lashes saving him from meeting anyone’s eye, though that didn’t stop Joan trying. She thought if she tried, and succeeded, he’d be grateful.

Federico parked carefully. He took his time getting out of the car, retrieving his overnight bag from the back seat, and something else, some sort of soft toy, luridly green against the car door. Perhaps his mother was getting senile now, finding comfort in those sorts of things. Or perhaps the toy was his: Joan would not have been entirely surprised to find that Federico slept with something stuffed. Waving through the window, she saw him wave back and head toward the house. She met him at the door.

“Federico, lovely to see you.” She touched her hair and felt cobwebs and dust. “Oh, I’m such a mess. We’re doing DIY. How are you?”

Federico set his bag down on the doorstep and pulled the green toy—an alligator—over his right hand. His fingers entered its snout. They brought it to life. “Terrible,” he said. The snout moved in time with the syllables; the pink tongue flashed. Federico’s voice sounded unusually hoarse, and he was speaking with a European accent, presumably Italian—his mother was Italian—that he’d never possessed before. “I’m sicka this journey. I’m sicka my Mama. How are you?”

“Oh,” Joan said. She was laughing, but she didn’t know why. The whole thing was too odd to strike her as funny. It was too strange that Federico should have brought a puppet along, today, after she’d found that old brochure of Claire’s. It was confusing. The feeling the alligator gave her was the same feeling she’d had with Suzanne: that this shouldn’t be done in public, that it was silly and puerile, but also somehow dangerous, somehow kicking at a vital support; and that the kicking was aimed at her, in the end: her inability to get the joke.

“Let me in,” the alligator said.

“Of course.” Joan stirred and stepped back. “Sorry, Federico. Please, come in.” What else could she say? “The kettle’s on. Henry’s nipped out. I don’t suppose you saw him when you came up the road?”

Guests were not normally allowed in the kitchen, or the living room, both of which had little signs nailed to the doors that said private, but at some point this had stopped applying to Federico, who was so quiet, so deeply unassuming, that Joan had felt compelled to make an exception for him, to show him that—in this small sense, at least—he could be an exceptional man. She poured him a cup of tea.

“You not gonna sit down?”

“Oh yes.” Down she sat. Federico held the alligator up on the table. It was watching Joan, who forgot to fetch her own cup, who sat in a daze, not asking questions.

“So you finally decide, don’t you,” the alligator said, at last.

“Decide what?”

“Federico. He not worth it.” Joan opened her mouth, but the toy continued: “It’s okay. Most people, they give up quicker than you. You almost make him believing you actually like him!”

“No,” she said, “that’s not what I think at all. I’m sorry. I’ve had a strange day. And the puppet…” It was hard not to look at the alligator, but she made herself look at Federico, his sad, sloping eyes, averted, of course.

“He’s giving up on himself, you know. Of course you know. You can sense it. Him and his Mama, forever. When she’s gone there won’t be nothing left. It is cruel, though,” the alligator said, “to change your mind today. You have invite him for dinner—or do you forget?”

She had forgotten.

“No,” she said, “of course not. I just have to finish making up your room. Would you give me a minute?”

She went to the utility closet and gathered the warm sheets out of the dryer. Upstairs, she made his bed. Then she went to Tessa’s room, to let her out. She was relieved to find the crawl space door still closed. It meant Tessa had not been teasing, had not withheld from her the means of escape. She twisted the handle, and the door released. Tessa was still lying on her back, still gazing up at the wreath of lights, but there was something sitting on her stomach. Joan’s heart gave a single massive thump. Tessa turned to look at her. The thing turned too.

“Leave me alone,” it said, in Tessa’s deepest voice.

Joan fell backward away from the crawl space. Somehow she scrambled across the hall toward her own room, shut the door, even locked it—they had a tiny key in the lock they never used, though once upon a time they had turned it if they ever made love—and ran to the far side of the bed, her side, where she sat on the floor, already feeling silly for how she’d reacted. There would be an explanation. Tessa would’ve found some old toy that Claire had missed. Maybe she’d found Suzanne—though it hadn’t been Suzanne. Joan had seen a dark color—brownish, perhaps, or greenish, like the mold in the bottom of the cups. And a smell. Had there been a smell? Had Tessa been keeping something horrible in there? Why did Joan have to deal with this? It was ridiculous, it was unfair. It was nearly Christmas. She ought to be putting the last cards on the mantelpiece and getting the lamb in the oven. Why now?

The house had fallen quiet. She would just stay here. Maybe she needed to lie down for a minute. It was not like Joan to lie down in the day, she thought it weak and slovenly, but the circumstances, really, were extraordinary, enough to slip her shoes off and settle on the bed, among the pale decorative cushions that Henry grumbled about having to remove and stack on the love seat every night.

Muster’s Puppets—it was all because she’d found that bloody brochure. She had puppets on the brain. They had taken the children on a journey to the moon, but they’d taken the adults too. She’d sat in the darkness, rolling Richard’s pram back and forth, an instinctual rhythm, and watched the puppeteers maneuver their spotlit characters into a rocket, then lift them into the air, light as paper, while projected stars wheeled across the back of the stage. Amazing, the capacity to efface themselves, to draw the whole crowd into the story, which was a simple one, of course: of boredom at home, then travel, then adventure that outstripped their appetites for it—the moon-puppets looming, their limbs lit blue—and then, at last, the relieved return, and the moon reduced to what it had previously been, just a picture in the sky.

There had been questions too. One of the puppets, the red one, had asked her friends, the children watching, even and especially the creatures on the moon, what happiness was. The question had obsessed her throughout the show, and the answers changed—of course—depending on whom she asked. Her friends said a wonderful book, or a new adventure. The children said it was a tingly feeling, or a sense of being warm. The moon-men responded in a warbling language that she couldn’t understand. And when they finally returned, after the moon-men had chased them off, after they had managed to repair their rocket and then to land it again without crashing, they had kissed the ground like demonstrative Americans, and the red puppet had announced that happiness was home.

Joan had not thought of this for years, the papier-mâché moon, and the cheap little tear that had come to her eye, which she’d refused to feel ashamed of, though one of the mothers had smiled at her, slightly weirdly, when the lights came up. Claire had tried to recreate the red puppet, Joan remembered. That was the point of Suzanne. And something else too: something Claire had said, that had prompted the confiscation. Joan had marched Claire out of the breakfast room where she was, it was true, bothering the guests at breakfast, asking silly questions in Suzanne’s silly voice—asking them, maybe, what they thought happiness was—and she’d told Claire that if she didn’t stop it there was going to be trouble. But Claire hadn’t yielded. She’d looked at Suzanne, and Suzanne had looked at Joan, its eyes goggling, and said, “You don’t have any happiness. It doesn’t want to live with you.”

Funny, in a way, in retrospect. Little girls don’t know what they’re saying. They misbehave, they’re punished, they let fly with some new language to express their rage, and it’s all forgotten in the space of an hour. Joan didn’t respond, except to put Suzanne in the crawl space; but she didn’t forget, not completely.

Joan heard a footstep—someone outside. The door rattled. A pause; another attempt; then: “Joan? Have you locked the door?”

It was Henry’s voice—his normal voice. “Henry? Is that you?”

“It’s me,” he said. “Let me in.”

She ran and touched the little key, and was almost impressed with herself, with her body, to see her hand shaking. The adrenaline.

“I fetched Richard,” Henry said. “We brought a takeaway. Chinese.”

So much for the lamb. But that didn’t matter. He’d brought dinner, he was here, he was sorting it out. Kind, dependable Henry. The key turned, and the door came open. There he was, in his waterproof jacket, with a puppet on his hand: some sort of shaggy doggy beast the same silver as his hair.

“What on Earth have you been doing?” asked the beast, but it was Henry, it was Henry’s own voice.

“You’re all having fun with me, aren’t you?” Joan cried. “You’re all in on it together. Is it meant to be a joke? Was it Claire’s idea?”

“What’s going on?”

“Stop waving that thing around, Henry, or God help me, I will rip it off your hand.”

“Federico said you were acting strangely. He said you’d lost your voice.”

Hearing this, Joan thought quite calmly that she might have gone mad. Wasn’t that what madness was—believing in a version of events that didn’t tally with the versions of others? Seeing the innards of your head in the world outside?

“Where’ve you put it?” the Henry-beast asked.

“Where’ve I put what?” Joan asked angrily, but she thought she knew what he meant. He meant Suzanne. Fine. If that was what they all wanted, Joan would find it. She ducked inside the crawl space and turned the light on. The stacks of boxes, untouched for nearly twenty years, the cracked old suitcases and soft bags stuffed in between them, materialized. There were plenty of black trash bags too, but when Joan started opening them they only held ancient yellowed duvets or underwhelming Halloween costumes, like the acre of torn-up sheets she’d once wound with a patience now unimaginable around Richard’s pajamaed limbs. Maybe she should stay in the crawl space, with the things she remembered arranged solidly around her, until whatever was happening came to an end.

“The food’s getting cold,” Henry called.

She had not found Suzanne in any of the bags. Despairing, she opened a box, and saw her mother’s cutlery. She opened another and it was full of crumpled yellow newspaper with three of the Toby jugs nestled inside. Their faces stared up at her, rigid and rosy with gin. The central jug was the one she reached for. This, unusually, was a woman: a stout, matronly figure with bloated cheeks and a dark blue tricorne hat, out of which—had you used the jug as a jug, which Joan’s mother never did—the liquid would have poured. There had only been two women in her mother’s collection. The rest of them, twenty-five or so, had been middle-aged men, some drinking, some with pipes or snuff, all squatting in the glass-fronted cabinet that dominated the dining room, their bulbous glazed chins and bellies shining. The blue woman had been the only jug that had ever appealed to Joan, though she couldn’t say she liked her. It was more of a fascinated fear.

She picked her up and marched her back to Henry. “There. Is this what you want?”

Henry smiled—he almost looked relieved. “All right. Let’s go.”

The sweetish smell of Chinese food struck her as she passed through the door. There they all were, arranged around the kitchen table like a family photograph just waiting to be taken: Federico with his alligator, Richard with a carved wooden knickerbockered boy, Tessa with her rotten animate compost heap shedding dark filaments on to the floor, Neal—since when had Neal arrived?—with a faceless lump like a cricket sock packed with dough, and Claire, terrible Claire, her face inside the raised hood of the black windbreaker still swollen from crying, holding up the buoyant dome of Suzanne’s head, its rice-cake-rubbled surface. One of the goggly eyes had fallen off, but the other adhered and swiveled, looking at Joan with old dislike.

The sweetish smell of Chinese food struck her as she passed through the door. There they all were, arranged around the kitchen table like a family photograph just waiting to be taken: Federico with his alligator, Richard with a carved wooden knickerbockered boy, Tessa with her rotten animate compost heap shedding dark filaments on to the floor, Neal—since when had Neal arrived?—with a faceless lump like a cricket sock packed with dough, and Claire, terrible Claire, her face inside the raised hood of the black windbreaker still swollen from crying, holding up the buoyant dome of Suzanne’s head, its rice-cake-rubbled surface. One of the goggly eyes had fallen off, but the other adhered and swiveled, looking at Joan with old dislike.

Henry joined them, turning the Henry-beast to face his wife. They were all looking at her expectantly: They wanted her to say something. Presumably she was meant to use the Toby jug. She lifted it, the pottery cool in her hands, rough at the lip where the glaziery stopped. The Toby-woman’s mouth could not be manipulated, but Joan could bob the jug up and down as she talked.

“Well,” she began, then stopped. Her voice was meant to change, wasn’t it? Only Henry’s had stayed the same. Poor transparent Henry. He didn’t get the joke. She was only just beginning to get it herself.

She pushed her tongue down and narrowed her throat and aspirated hard to get a wheezy sort of sound, like her mother in the later stages of emphysema—a sound she’d never forgotten, but never attempted to reproduce. What she wanted to say was how glad she was to have them all home for Christmas, and that although Chinese takeout wasn’t exactly what she’d had in mind—it was meant to be lamb, she’d gotten a very good lamb shank from the butcher—that really didn’t matter, because they were all together, and that’s what counts. But what issued from her mouth was wheezing vowels, long and painful, with no stops, no consonants, in between. The family was still watching, but the expectancy had drained from their faces. They looked dismayed.

“What’s wrong with her?” the Tessa-monster asked.

“She’s lost her voice,” said Neal.

“I haven’t,” Joan insisted, “I’m talking,” but the words came out as more wheezing, which they all ignored.

“What should we do?”

“Where could it be?”

It was Suzanne, on Claire’s arm, that rose from the table. “She must have swallowed her voice. We’ll have to look for it.”

Taking up one of the table knives, Claire advanced.