Once long ago—before Georgia was born, before getting married, in the days when apartments consisted of pee-stained futons and speaker wires tracing across the floor, guitars laid lovingly in their plush cases, overflowing ashtrays, no artwork, no plants, only temperamental cats for decoration—Carrie wrote a song about divorce that became a college-radio hit. It contained several references to fucking, which excited the alt-rock frat boys, and something about French cigarettes, a hotel room, and a lost map, the woman in the song admitting she’d lost it. How tenuous, yet sinuous, the cords of memory! Now, in a Waffle House in Salisbury, Maryland, Carrie watches Georgia demolish a hideous accident of hash browns like a vulture. Her iced tea is sweet—she forgot to specify—so sweet it makes her feel dizzy and hungover, though she’s had nothing to drink for days. “When I was your age,” Carrie says, “Grandpa Carl would spread out a map in a place just like this, all across the table, and make us figure out where we were going.”

“So let’s get a map. I want to try.”

“I’ll get an atlas for the drive home.”

“But I won’t be interested then,” Georgia says. She’s nine. Her T-shirt, a hand-me-down from family friends with two older girls, is stenciled with a line drawing of a woman who looks like Courtney Love and the slogan girl power. “I’m interested now. In two days, I’ll be bored by maps, and you’ll just yell at me about wasting money.”

“Yes, that’s probably exactly what will happen.”

“Also, you’ve been here a million times. I bet you don’t even really need your GPS.”

“We always got lost visiting Miss May,” Carrie says. “There’s all these little turns. You’ll see. Grandpa Carl used to say they change the road signs in Crisfield every six months just to keep the tourists away.”

“It’s weird, coming to someone’s house for the postmortem,” Georgia giggles. Her babysitter, a doctoral student in classics, taught her that word.

“Do you realize,” Carrie says, “that I used to know the girl in that picture? On your shirt?”

“That’s not a real person.”

“Sure it is. She used to be a rock star.”

“Then how did you know her?”

“Georgia.”

In this story, as in so much of her life, Georgia is the child who cracks wise, the way she used to perform somersaults across the living room. You can never gauge how interested adults are, certainly not by the noises they make; to keep their attention you have to threaten to break things. In my day we learned it from sitcoms or shitty relatives, Carrie’s thinking; now it’s just in the water, like microplastics and benzodiazepines.

“Oh yeah,” Georgia says. “You were a rock star, a kinda-sorta rock star, and you made a lot of money, but then you lost it, and you retired.”

“I got tired. I took a break. Then had you.”

“And now you’re on Twitter all the time.”

“That’s not a job. I have a job.”

“But you always say you never make any money selling houses.”

“Any money is a figure of speech.”

“I’m done,” Georgia announces. The pile of hash browns is two-thirds diminished. “I’m going to the bathroom.”

A woman and her daughter at a restaurant table. A yellow field, a white rectangle, two brown dots. The woman is remembering but not mentioning, for her daughter’s benefit, that the last time she was in a Waffle House each table had an ashtray. A square ashtray the size of a waffle. It was 1995 or 1996. Her lungs ache. A yellow square on a white rectangle.

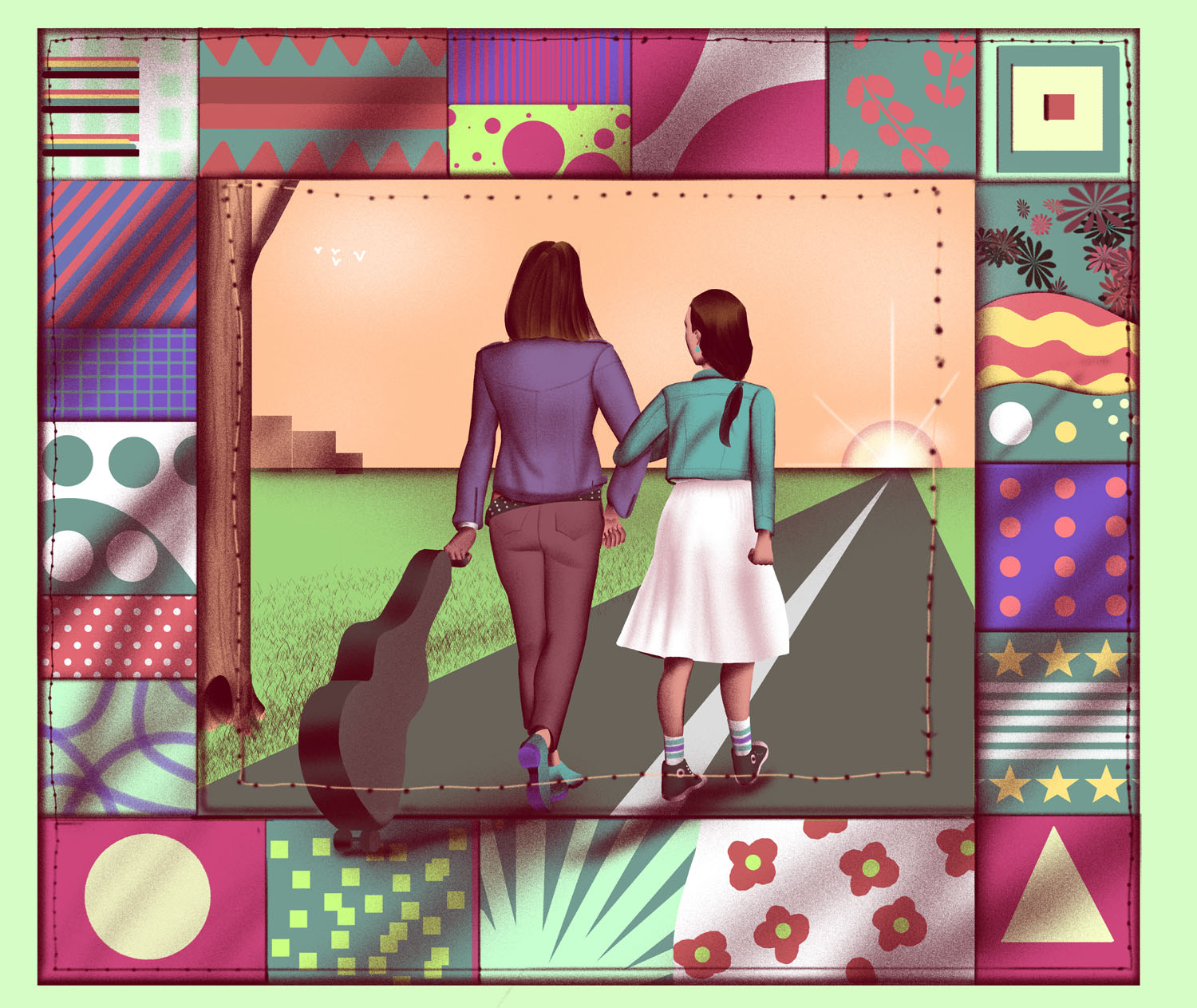

“Miss May was an artist,” Carrie says, back in the car. “She was an amazing, visionary, mystical artist who worked in quilts. When she was little there wasn’t any way for her to learn to paint or be a sculptor. That wasn’t part of her world. So she had what she wanted to express, and she translated it into quilts. People from all around the world buy them. Grandpa Carl owned the gallery in New York that sold them. He was basically her agent, her business manager. He helped her sell the quilts so she could focus on making them.”

“Are the quilts really expensive?”

“Yes.”

“Like, five hundred dollars?”

Carrie curls her lips over her teeth, trying not to smile. Georgia lately has become fascinated by how much things cost. Carrie hopes it isn’t an indication of how things are at Lower Hudson Valley Waldorf. “Honey,” she says, “remember when I bought our house? Miss May’s quilts paid for it. All the Miss May quilts, I sold them, and then I bought the house. So they gave us our place to live. That’s how much they’re worth.”

“And they gave her a place to live.”

“Of course they did,” she says, startled. “Miss May had a good life. She had everything she needed.”

“I wish I could have met her,” Georgia says. The green bank of the roadside scrolling past slowly, speeding up.

“I wish you could have seen her working,” Carrie says. “That’s the main thing.” She remembers now what she had meant to say to the waitress after taking a sip of that excruciating tea: No sugar in my bowl…no sweetness down in my soul. “Do you even know what quilting is?” Carrie asks. “I mean, do you know what goes into a quilt?”

“Nope.”

“I’ll get you a book about it.”

Only when she pulls up—turning into the driveway, Georgia sprawled asleep across the back seat—does Carrie remember that there are two houses now on the property: the old house, its white siding mossy and gray, and the new house, all angles and three-story windows, up there on the bluff. The last time Carrie was here it had been nothing more than a skeleton of studs and peeling Tyvek hidden in a stand of loblolly pines. All the old cars are gone from the yard—Miss May’s white DeVille, the ancient Ford pickup, the rusting body of Carl’s MG Midget up on blocks where he’d left it after some disastrous road trip in the seventies. The old house looks even smaller than before as she drives past it, tires scratching up the hill, the live oaks gone and a terraced garden of enormous rhododendrons in their place. The new house so…hideous. She can’t think of any other word.

“Wow,” Georgia says, awake now. “It looks, like, kind of accidental. This is where she lived?”

“No,” she says. “Yes. I mean, at the end. This is where she died.” And then, seeing Moni at the door, shading her eyes: “Listen, don’t say anything, okay? Be nice.”

“I’m always nice.”

“Be nicer.”

Moni had booked the room on her phone while getting off the train at Penn Station, had unintentionally clicked the button for King Suite instead of Standard. Living room, kitchen, balcony overlooking a low river winding through cattails. “That’s a swamp,” Kevin had said when she’d opened the curtains. “We have a room with a view—of a swamp.” The only place that delivered was Domino’s, so Moni had driven all the way to Euston’s, ten miles each way, to get crab cakes and hush puppies, and warmed them in the room’s tiny oven while Kevin finished his conference call.

It’s April. They’re eating on the couch with the balcony door open, the Bay air streaming in. Kevin is paleo but kindly isn’t complaining, gobbling a slice of cake and licking his fingers. “So it was always your Aunt May just on her own,” he says, restarting the conversation. “There was never a man around?”

“She was celibate,” Moni says, digging a plastic fork into a container of coleslaw. “That was the word she used. ‘I found out everything I needed to know about men before the age of eighteen,’ is the way she put it.”

“That’s harsh.”

“You never had a maiden aunt growing up?”

“I had Aunt Carrie and Aunt Tasha. They were of the other persuasion, that’s what Pops used to say. Took me till college to figure out what the hell he was talking about. Not the same thing, I know. They did give out the best presents.”

“That was Aunt May,” she says, stretching out her legs on the carpet. “Loved kids, loved having us come to visit. Threw house parties every Labor Day and Memorial Day. Cookouts, pig roasts, Thanksgivings, Christmases. ‘I’m happy to be the host as long as I don’t have to do any of the work,’ she’d say, ‘as long as everyone cleans up and goes home afterward.’ Daddy and Grandpa Carl did all the hard work. Carrie and I washed the dishes. Shawn did, too, when he was old enough. But Carrie and I were pretty lucky because we got to stay over in the house, on a mattress at the foot of May’s bed. ‘Where I can keep an eye on you,’ she’d say.”

“You two were that close?”

“You know how kids are. We were best friends for two weeks a year. And then when we got older our parents sent us to sleepaway camp together, at Catoctin, and Aunt May picked us up and brought us back here afterward for a week. She liked having us around, having us together. Don’t ask me why, exactly.”

“Wish I could have met her.”

Done eating, she breathes in, deep, a full count to ten, and checks her FitBit. One hundred ten over seventy, not bad. “You’re a good boyfriend,” she says, leaning over and catching him by the ankle. “Way better than I deserve. I’d never sign up to get pulled into this kind of drama.”

“I’m just here for the heavy lifting and the seafood,” he says. “Anyway, everybody’s got family. Near-family, whatever. You have to meet them eventually. It’s all one deal.” His jaw works at her with all earnest intent. Courtship, marriage, family: He read a pile of books about it, he told her early on, and piles of books are not his thing. He’s auditioning, trying out. Charging in, head down. “So just lay it out,” he says, “all the facts. I’ll tell you if I get lost.”

“I’m forty-three years old,” she says, not looking at him, “and this thing, you know, Carl’s deception, the fraud, whatever, started before I was born. It’s just layers and layers. I’m so fricking desperate to move on. I think Carrie is too. I guess. She’s weird on the phone.”

“But she’s basically a good person.”

“If you’re saying, Did she know what Carl was doing? She didn’t. I believe her. I think.”

“DeRonn texted me a picture of one of her old albums. She was fine as hell in 1995.”

“That’s just what I need to hear.”

“Not my thing,” he says. “Skinny fragile white girls.” He’s changing into a fresh T-shirt, about to hit the hotel gym. “My dad always said, when a white girl gets that look on her face, don’t say nothing, just run the other way.”

“Sound advice.”

He’s wearing his AirBuds now, or whatever those things are called, and doesn’t hear her. Though he takes care, and palms the door, not to let it slam.

It’s been almost a year: the longest by far she’s been with anyone, post-divorce. Maybe it doesn’t matter so much, the difference between thirty-five and forty-three. That he doesn’t remember Eric B or Reagan. She stretches out on the bed. His whole orientation in time is different: His older brother, Jeremy, died in 2006 in Fallujah. That’s the shape of his world, his before and after. His warp. And he doesn’t know a thing about art. Not in the sense of I never took an art-history class in college, but in the sense that he’d never visited an art museum, at least not on his own, as an adult, until she dragged him to see Kehinde Wiley at the Brooklyn Museum, back on their second date. Not that he doesn’t try: His richest client, who plays for the Seahawks, is trying to diversify his portfolio, and she’s walked them through Chelsea galleries a couple of times. Just look for things that speak to you, she always says. As if she knows. I don’t have a degree, she said to Kevin once, I don’t know everything, don’t expect me to know everything. I do have a sensibility.

A woman lying at ease across a made bed. Arms drawn close to her body, legs in a Y. She left straight from work. Tailored pants, a raw-silk blouse. Her shoes kicked off. The room growing dark, the blue glow of the phone. More rectangles. A figure lying on a bed is a web, a series of cross-stitches.

In the hallway, the foyer, though it’s too enormous for that word (two floors of empty space leading up to a gigantic rectangle of sky), are three of Miss May’s last quilts, ones she’s only seen in the catalogue prepared by the estate lawyers under the heading Property of the Lincoln family, held in situ, access by family permission only. They’re part of the Migration series, she can see that much: the doubled motifs of birds cresting across the top and dark human figures creeping along the bottom edge. But here the birds and people are barely marked in the pattern; what matters is the color.

Two women holding hands, looking into each other’s faces. That time we learned to play poker, at camp, Carrie wants to say. Sticks of gum and Starburst were the chips. Crosslegged in the dirt outside Cabin 2, snapping bubbles, slapping bugs. Someone had a clock radio with a tape deck, playing “Darling Nikki.” You, Carrie wants to insist—for no good reason other than it’s true of Moni’s face in that light, her high eyebrows permanently skeptical—you haven’t changed.

“Wow,” Georgia saying, “there’s a lot of stuff in this house.”

“We left at five this morning,” Carrie says. “I had a work thing last night.”

“We stayed in a hotel in Salisbury,” Moni offers. “Just got here half an hour ago.”

“It’s all good,” Kevin calls from the kitchen. “The coffeemaker works. I figured it out.”

While Carrie and Moni work through the lawyers’ catalogue at the dining table—not even a catalogue, just a stapled sheaf of photos with bad lighting, which arrived at Carrie’s house via courier and required three separate signatures—Kevin and Georgia move from room to room, unlatching and opening windows, spreading curtains, testing the lights. The house has sat unoccupied and untouched for six years. Sealed, by order of the district attorney: Moni broke the orange tape on the front door. Now, suddenly, it smells like coffee. The air moves. Georgia bounces on Miss May’s bed, opens her closets, sneezes. “Phew,” she says, “there’s mold on these clothes.”

“We’ll let the ladies handle that,” Kevin says. “Do the sliding door.”

“My grandfather cheated Miss May out of a lot of money,” she says, testing the latch. “Did you know that? He handled all of her accounts, and he embezzled, like, a billion dollars from her.”

“Not a billion,” he says. “A lot, though. That’s what I heard.”

A tall Black man and a skinny white nine-year-old with red hair in two braids, in chairs, facing each other, on a balcony overlooking Daugherty Creek. The flowers in the ruined planter have sent up a few shoots.

“There’s a picture of me downstairs when I was, like, five. On the piano.”

“It’s a beautiful house, that’s for sure.”

“Even though Grandpa Carl stole from her, Miss May still had a lot of money.”

“Do you like sports?” Kevin says, for a moment feeling like he’s doing this all wrong. “Do you like the Seahawks?”

“Mom says sports are the opiate of the masses.”

“Is that a no?”

“I go to soccer camp. Basically just because it’s the cheapest camp in Hudson. I’m pretty good too. Last summer I was a goalie the whole time.”

“That’s the hardest position.”

“I got a lot of bruises.”

“Well, anyway, that’s what I do,” he says. “I work in sports. I’m a sports agent.”

“Oh,” she says. “What does a sports agent do?”

“I represent players on pro teams who make a lot of money.”

“Do you make a lot of money?”

“I do okay.”

“Mom says that’s what rich people always say.”

He laughs. “I’m not rich.”

“You could be regular-people rich,” she says. She doesn’t know why she says these things, these balloons she floats in the adult air. Adulthood, she’s suspects, involves choosing your words very carefully, so that anything interesting doesn’t actually escape. “That’s what we are,” she says. “Regular-people rich, but not New York rich.”

Two women sitting with their coffee at one end of a long dining table, a table built for twenty. Like an umlaut over an i, their arms outspread. Papers, phones, Moni’s laptop. Sitting just close enough that their hands could touch. Carrie is thinking about how she can always tell, with a glance, whether a woman her age is a mom. It’s a mark. The forehead has a crease of incipient worry. Look at me, she wants to say to Moni, and tell me, honestly, how devastated I look. Tell me you don’t have an eye for white women and their webby hands, their nests of wrinkles, their protruding eye sockets, like the caged Perdue chickens of Salisbury, Maryland.

“I remember the day your dad had this table delivered,” Moni says. “It took six guys just to carry it through the door. And my dad took one look at it and said, that is one white elephant.”

“Miss May loved it, though.”

“Don’t get me wrong. It was her favorite piece of furniture. I just don’t know what to do with it.”

“People will drive a long way for May Lincoln’s estate sale. They’ll bring trucks. I wouldn’t worry about it.”

“You remember the bananas flambé?”

“Remember the Night of One Hundred Cheeses?”

“The pig roast.”

“The vichyssoise.”

“And where the fuck did all those people go?” Moni says, looking up at the ceiling. “How the hell are we doing this all alone, Carrie?”

“Where’s Shawn? Why isn’t he here?”

“Shawn’s on call. He’s always on call. Or at a soccer game. He’s got four kids. He said to just send him the check for his half. He doesn’t want to know the details.”

“I finally got Mom to call me back last week,” Carrie says. “She was sympathetic. She said, ‘I spent twenty-seven years cleaning up Carl Lowenthal’s messes. Now it’s your turn.’”

“If there were a lawsuit, she’d be named,” Moni says. “Accessory to fraud. Big-time. I’m sorry. It sucks to hear someone say that about your mother, but there it is.”

“I know. General incompetence isn’t a winning legal defense.”

“I think it was way more than that. She did his books. She’s liable, Carrie. She owes me—financially, and at the very least I deserve a written apology.”

“You absolutely do,” Carrie says. “I’d sue her for one myself if I could.”

On the balcony, upstairs, Kevin says something to Georgia and she giggles. A boat roars past on the river. A whiff of brackish water, the foam of a wave. Moni feels herself going damp under the arms. The days she spent here in the summer, those long weekends, back from camp, waiting for Dad to pick her up. Also the two weeks her parents went to Italy that one time. Miss May refusing to turn on the central air till the evening, leaving every window open—in those days she would shower in cold water three times before lunch. There wasn’t a pool anywhere nearby. You could swim in the river, but it was warm and green and her skin shrank from it. The constant surging of the sewing machine and the radio station from Washington playing Mozart and Brahms.

“So this is what we’re looking at,” she says, finally. For the lack of anything else to say. “The inventories conflict in three ways. Your dad’s last catalogue said there are sixty-seven finished quilts. This one from the lawyers lists three more, plus one unfinished still in the studio. Your dad’s catalogue said Lowenthal Gallery still owned fifteen as of his decease. Miss May left a handwritten list saying Lowenthal Gallery owned seventeen. Your dad’s says that Lowenthal sold Study for the Migration Series to a collector; Miss May’s list says it’s still here in the house somewhere. So what we’re supposed to do today is make sure we know exactly what’s here, first, and second, Kevin and I have to wrap up all the quilts and take them to storage, and third— ”

“Just tell me what you need me to do. I’m good with scissors and tape.”

“I needed to see your face. That’s why I asked you here, Carrie. I think some things have to be done that way.”

“I should have come to the funeral,” Carrie says. “I’m sorry I didn’t. It’s haunted me—seriously.”

“No, there would have been a scene.”

“Well, it would have been worth it. Miss May deserved that scene to happen—does that make sense? We should have all had it out, face-to-face. That way you and I wouldn’t be sitting here feeling shitty and helpless.”

“Nobody wants to get into it, that’s for sure. It’s just you, me, a Japanese collector, and the Brooklyn Museum.”

“You’re kidding me.”

“If we can account for them all. Major retrospective. But no accurate provenance, no show.”

“I appreciate that. I appreciate you saying we.”

“Well, I appreciate you coming. And bringing Georgia. How sad is it that we’ve never met? And now she’s a little fully formed person.”

“Not that fully formed, I hope.”

“You know what I mean.”

They keep shooting out these phrases, as if phrases make a conversation, or little polite apologies amount to big consequential ones. Not that, Moni is thinking. Not that she was expecting her to apologize. She did send me that one panicky email, with no paragraph breaks, about all the ways Carl hid his actual finances, and which closed with I’m devastated and I understand if you never want to see me again. Maybe that was supposed to count. You could use it as a white-lady epitaph, she’s thinking, leafing through her folder for the lawyer’s room-to-room inventory, slap it on a stone to keep people from wondering too long who’s buried underneath.

May Lincoln Studio, May 15, 2012. This is the caption on the photograph that the lawyer’s office sent, taken the day the house was sealed. Moni studies it, standing in the studio’s doorway. Nothing has changed but the dust. Miss May kept a clean house. The work table and the swiveling stools; the bobbins, hundreds of them, neatly organized in plastic drawers along one wall; the old Singer she inherited from Grandma Lincoln, the commercial-grade machine she used for studies and sketches. A large cork bulletin board, with a sheet of yellow legal paper, covered in Sharpie in a loopy cursive hand: Abstraction is just another name for God’s perspective.

“She kept her quilts covered with a sheet until they were done,” Monique explains to Georgia. “To keep the colors from fading. And because she wanted privacy while she was working.”

Georgia has been moving tentatively about the room, peering at things, her hands held artificially at her sides. “Mom,” she says, pointing at the covered quilt on the center table with her chin. “Can we look at it now?”

“Moni?”

“Go ahead, take the sheet off,” Moni says. “Tell me what you see.” She takes out her phone and begins filming. “We’ll make a little documentary. It’s a historical moment.”

Cloth swishes as it piles on the floor.

“I see dots on a yellow background, like polka dots,” Georgia says. “They’re in patterns of…eight? Eight different-colored dots, one blue dot in the middle. Look, she taped a Skittles package to the table. They’re supposed to be Skittles. Except there’s no blue Skittles, are there?”

“Turn the quilt over,” Carrie says.

“She sewed something on the bottom corner. It says, For Trayvon, Blues.”

“Do you know who that is?”

Her eyes shift from one face to the other and drop.

“Don’t make it a test,” she says. “If it’s a test, that ruins it.”

“I would eat crabs three meals a day,” Kevin says to Georgia, in the car. “And oysters. Used to be Maryland ran out of oysters. Now they’re bouncing back.”

“You must go to the gym a lot.”

“Every day. That’s how I stay focused in life.”

“We have an exercise bike. But I think I ride it more than Mom does. I’m way more focused than her. At my old school I got 4s in organization and participation.”

“Is a 4 like an A?”

“Is an A the best?”

“Basically.”

“Then yes.”

“It’s always been just the two of you, right? You and your mom?”

“I don’t have a dad. Mom used a sperm donor.”

“Roy’s Seafood, coming up,” Kevin says, glancing at his phone. “On the right-hand side. Yelp says there’s no sign.”

“Why would you have a restaurant with no sign?”

“If you’re good enough, you don’t need one.”

“When we were twelve,” Moni says, licking Old Bay from her pinky, “Miss May hired us to be her research assistants for two weeks. We had to go to the library and read every book about Harriet Tubman and prepare a typed report.”

“And then,” Carrie says, “she drove us to every known site associated with Tubman on the Eastern Shore.”

“Swamps in August.”

“We took pictures. She made drawings.”

“I basically died,” Moni says. “I had so many mosquito bites, my skin broke out in hives. Dad didn’t speak to Miss May for months after that. She said it probably made me immune to malaria and dengue fever.”

“That summer changed my life,” Carrie says. “It made me an artist. She made me an artist.” She’s pouring herself another glass of wine; she doesn’t notice Kevin’s long look, frankly staring, eyebrows parenthetical. Moni shakes her head at him but he doesn’t notice, or pretends not to.

“I mean she prepared me to be an artist. Seeing the way she did things. She was harsh. She was mean. It didn’t matter if we didn’t want to; she just kept going.”

“She had to be,” Kevin says. “Nobody gave her anything.”

“She saved all her tenderness for her work,” Carrie says, “which is the way a woman artist has to be. I learned all that from her.” She feels wild-eyed. “We only ever talked once about me becoming a musician. She said the most low-down men in the world work in those bars and clubs. ‘You better learn how to scratch and kick, girl.’ ”

“Wise words,” Kevin says. “But how can you compare—”

Moni holds up one finger.

“And afterward,” Carrie says, “after it happened—”

“Carrie,” Moni says, “I haven’t told Kevin.”

“Oh! Sorry. Yeah. I was raped, in 1994. In a bathroom at a club in Cambridge. The guy was managing my band at the time, actually. I didn’t know what to do. I didn’t go to the police.”

“That’s terrible,” Kevin says. “I’m sorry.”

She watches Georgia flick her fishing rod expertly, the way Carl taught her, the line making a long arc over the water, falling into the shadow of an overhanging tree.

“Fortunately, I suppose, he OD’d in 2000. I never think about him. My life went on. I went solo, had a career. Got married and divorced. Had a kid. But what I was about to say was that after it happened, I felt like I’d failed Miss May. I should have killed him. Or at least left a scar. I never told her about it. But I desperately, desperately wanted to.”

“She would never have blamed you,” Moni says.

“I didn’t think she would but she might have said she warned me.”

“Mom,” Georgia yells out, “I caught a can of Coors Light!”

Carrie says to Moni, “You know, in college I recorded an entire album of songs about the quilts.”

“You did?”

“It was terrible. It was so…Lilith Fair. But I did it, I put the whole thing on DAT, made one cassette, then brought it down here and played it for her. It might still be around somewhere.”

“What did she say?”

“She said it was nice. Nice music. She said I had a good voice.”

“Ouch.”

“One of the songs was about Harriet Tubman. It was called ‘Harriet’s Blues.’ I’m so embarrassed just saying that out loud.”

“We all do embarrassing things in college,” Moni says. “Kevin permanently scarred himself with a brand—for example.”

“I’d do it again,” he says, “in a heartbeat.”

“Because Black people haven’t been branded enough times in our history.”

“I had the same argument with Carl when I got my first tattoo,” Carrie says. “He nearly threw me out of the house. At Passover.”

“I didn’t know he was religious.”

“He wasn’t. It’s about the Holocaust, not about Leviticus.”

“That’s not the same argument,” Kevin says.

“Of course not,” Carrie said. “It’s a figure of speech. Tattoos, brands. It’s an analogous thought. I was just making conversation. Also, you know, Kevin, you don’t have to like me. Men often don’t.”

A man and a woman curled on opposite sides of the bed. The letter S and its reflection. The mark on a map for a bridge or possibly a railroad crossing. The sheets, freshly washed—“Thank God the machine works,” Kevin had said—reek of Febreze and Dawn. Kevin had vacuumed so vigorously he left grooves in the carpet. A man who tames a dirty house.

“You don’t have any white people you’ve loved,” she says. “You don’t know what it’s like. Just because I never mention her doesn’t mean a thing. She was legit the closest thing to a sister I ever had, other than my cousins, and they never seem to leave New Mexico.”

“Put it another way, then. Could Miss May have found another gallery?”

“Of course.”

“Did she ever consider it?”

“I have no idea.”

“Let’s say that’s a no. And let’s say I know what I’m talking about, being in the business of representation. The guy had a monopoly on her work, probably the most famous person in her field—”

“Of course not.”

“Okay, fine. Whatever. A major player. Totally naïve to begin with, and then given nothing but bad advice. She thinks of her agent as family, and treats his one child actually like family, meaning she’s down here, as a child, on her own. They have that level of trust between them. And he’s systematically skimming off deals, kiting checks, keeping double books the whole time. That is a long fucking con, if you ask me.”

“There’s this short story,” Moni says, “called ‘Everyday Use.’ Alice Walker. You know what I’m talking about?”

“Sure. I think I read it in middle school.”

“It’s a perfect story,” she says. “A little too perfect. That’s why it’s good for middle schoolers. The quilter in the story has a daughter who’s timid and stays at home, and another daughter who went to college and turned Afrocentric.”

“And her Hotep boyfriend.”

“Something like that. You remember what happens at the end?”

“She cuts the quilt in half.”

“She gives the quilt to the meek timid one, who’ll keep it on her bed. I wrote a long paper on it my first year at Columbia. I tore Walker’s logic apart. I called her a self-hating Black artist. The paper was called ‘Contingencies of Value and the Paradox of Folk Authenticity.’ When it was published, I sent a copy to Miss May. She sent me back a postcard. It said, ‘Don’t spit on Alice. She knows just what I gave away.’”

“Am I supposed to guess what that means?”

“It’s not complicated. Render unto Caesar what is Caesar’s.”

“So that makes Carrie, what, Ivanka Caesar?”

“Keep your voice down. We didn’t ask to be born into this deal, either of us. I’m not exactly a paragon of filial responsibility. I’m making money with this shit as soon as I get my hands on it.”

“It’s not up to you to decide what the market wants. The point is, you get to do the selling. Nobody else takes a cut.”

“Says a sports agent. You know perfectly well it’s all cuts, all the way down.”

Carrie brought several indica strains with her, including one her friend Dreyfus in Sonoma developed years ago specifically for the aftermath of bad arguments, all in a little tin chest with compartments the size of a deck of cards. It goes with her whenever she’s on the road. What kind of life was it, back in the day, smoking whatever kind of skunk weed was being passed around? She has money in three cannabis start-ups, two run by former bandmates. It’s what an aging indie rocker does, if they’re not selling menswear or making thirty-dollar salads. Just to be safe, though there’s very little detectable odor, she opens all the windows and leans out, making sure not to drop the vape pen.

“It’s hot,” Georgia mutters from the bed.

“I looked everywhere. Miss May didn’t really believe in fans.”

“Then turn the AC on.”

“I couldn’t find the thermostat.”

“So we’re just supposed to sit here and melt?”

“Correct,” Carrie says, distractedly. “I wish I had my guitar. My fingers are itching.”

“There’s one hanging on the wall downstairs.”

“That’s not a guitar, sweetie. That’s Johnny Cash’s Gibson J-200. Some millionaire dentist traded it to Miss May for a quilt, back in the ’90s. It’s worth as much as this house. It probably hasn’t been tuned in thirty years.”

“It’s still a guitar. Go get it.”

In fact, Carrie remembers, stretching up on her bare toes to unhitch it from its hanger, she must have been the last person to play it—the only one Miss May considered qualified to even touch it. “Go get the guitar down,” May had said, the first time Carrie visited with baby Georgia. “Make sure there’s no cracks in it. I worry about it in the dry winters.” So she carried it very gently across the room, wishing she had those white auctioneer’s gloves. As she carries it now. In the dark, the varnish warm, almost pulsing, in her hands. It may have once belonged to Lead Belly, the dentist had apparently said. Ralph was present for the hand-off and reported that back to her. Which is BS, he added, I checked with some appraisers on the phone.

“Play for me,” Georgia says, stretching out her full impossible length in the sheets. “Play ‘Freight Train.’ Play ‘Little Liza Jane.’”

The tuners, thank God, aren’t original. She stretches the strings carefully, holds the body up under the light, taps the bridge. Solid all the way through; only dusty, leaving ridges of grime on her fingertips. Still meant to be played. The low E twangs convincingly. It was old when Johnny Cash bought it. How many times was it redeemed. She makes the shape of a B-flat 7. How many hands on this neck. A smell rises from it: resin, dust, tarnish. Used bookstores. Old leaves.

“You’re not playing.”

“I’m thinking,” she says automatically, what she always says when someone interrupts her with a guitar in her hands. She strums an open D. “I’m not afraid of you angry,” she sings, breathily, “I’m not afraid of you hungry—”

“I didn’t ask for one of your songs.”

“Sorry.” She switches to a lazy 1-6-2-5. “No one to talk to, nowhere to go—”

“Mom.”

“Okay, okay. ‘I got a friend in Baltimore, Little Liza Jane.

“ ‘Streetcars running by her door, Little Liza Jane.’ ”

Thunder. The night sky rolls and percusses. A breath of air, through the windows, a ripple of light around the fringe of trees across the river.

Rain swishes on the porch, sizzling on the roof.

A girl asleep, splayed across the couch, her toes caught in the net of a crocheted blanket. Georgia blinks when Moni turns on the light over the kitchen island.

“Aren’t you supposed to be in bed?” Moni says.

“Can you make me some tea too?”

“I guess so, sure. Honeybush, peppermint, Sleepytime?” A bright web in the sky, and almost instantaneously the fireworks crackle, a flam on a snare drum. “But then you need to go back to sleep.”

“I have a question for you.”

“Okay. Just one.”

“Was your dad friends with Grandpa Carl?” Georgia’s eyes are shining, which is a trick of the light fixture, a bizarre art nouveau statement that belongs in no kitchen anywhere. She looks almost feverish, but no: Moni decides it’s just a hunger for adults to say what they mean, in a child who spends entirely too much time around the kind of adults Carrie runs with—former cool kids; slack-mouthed dissemblers.

“Not exactly,” Moni says. “Though they spent a lot of time together. Actually it was my mom who really liked your grandpa. For a while they were very close, when I was about your age.”

“Is your mom dead too?”

“She and my dad got divorced when I was twelve, and she went off to be an actress, then an artist. She married an Austrian man and had two more kids. They live in the Alps.”

“But why didn’t your dad like Grandpa Carl?”

“I mean…they were friendly. They all had to show up here for the same occasions. But Ralph, my dad, was an engineer, and he didn’t really understand what Carl did. He had a pretty low opinion of the art business. It wasn’t about the money. He was glad that his mom was making money. He just didn’t understand what it was that made it so special. To him it was just a hobby, something she’d always done, something her mother did, and the idea that you could put it on the wall and some rich lady would pay ten thousand dollars for it—he didn’t like it. Period.”

“We used to have them hanging all over the house, in New York. When we lived in Grandpa’s apartment. Now we’ve only got one, hung up over the couch. Mom says it’s not a Miss May. Maybe it’s a copy. It looks just like those ones, the big ones in the hall.”

“Seriously,” Moni says, “you should go back to sleep, Georgia. Go back to the couch. Come on.” She leads her by the hand, around the railing, down into the sunken living room. It’s a Celestial Seasonings moment. “Lie down,” she says, and spreads the blanket over her, a zigzag pattern, another Miss May. She crocheted in front of the TV, watching the PBS NewsHour and Masterpiece Theatre.

“You know there’s a picture of you and Mom on top of the piano,” Georgia says. “Next to the one of me.”

“That was when I went to see your mom play in New York, when I was in grad school. I was a little scared of her. I mean, that voice! It made the hair stand up on the back of your neck. But then I went backstage and she hugged me and she was the same Carrie as always.”

“She does this thing where people recognize her, like in a restaurant? She turns her back to me, so they won’t look at me. She says, Never talk to strangers, but never ever talk to fans. Guy fans are the creepiest.”

“Music does weird things to people,” Moni says, with a yawn. “Sometimes your fans think they, I don’t know, they own you. I guess that’s what it’s like. You weren’t around, you’re not part of that, she just doesn’t want you to be collateral damage—sorry, that’s not the right expression. I’m tired.”

“You should go back to bed.”

“Only if you do too.”

“Turn out the light, I’ll pretend to be sleeping.”

Not knowing what else to do, Moni brings two cups of coffee up to Carrie’s room, closes the door, and sits on the edge of the bed. Lies on the bed. Puts her head on a pillow, facing the ceiling.

Carrie kicks her.

“Ouch,” she says, and Carrie opens her eyes.

“Georgia’s sleeping on the couch.”

“I know. I told her to.”

She closes her eyes again.

“Don’t go back to sleep. I brought you coffee.”

“There isn’t enough coffee in the world for this conversation. Funny, I almost said covfefe.”

“It isn’t fucking funny, Carrie.”

“Miss May said that the series doesn’t need it, it was just preliminary.”

“Where did she ever say that?”

“She said it to me.”

“It was part of the series when Carl showed it.”

“Carl was just hoping to sell it quickly, because it was smaller than the others.”

“Aesthetically, I think you’re wrong,” Moni says, “but financially, I couldn’t care less, because the Brooklyn Museum considers it integral to the series, and it’s not at all your business to make these judgments, and I can’t believe I even have to ask you at all.”

“I need something of hers, Moni, something she worked on, from her hands.”

“You’ve got lots of photos.”

“That’s just cruel. I grew up with these quilts. They were in my house. They were in my room. It’s not my fault that Carl was an asshole.”

“Those quilts were never intended to be your family’s property. That’s not what Miss May made them for. They weren’t gifts. They were just the ones that didn’t sell quickly enough.”

“Which is why I returned them.”

“After you auctioned off the others to buy a house?”

“That’s not fair. That was before any of us knew what Dad was doing.”

Someone is laughing downstairs, pans clanking in the kitchen, and it takes Moni a moment to remember what girl is in the house. She slugs the coffee, now lukewarm. For a second, she wants to say to Carrie, I forgot that was your daughter, I thought it was nine-year-old you. Or, for that matter, me.

“You know,” Moni says, “if you want it, you can have the Trayvon quilt. It’s unfinished. As long as you sign a contract saying it’s available for loan, you can keep it.”

“That is fucking outrageous, and you know I can never take that offer.”

“Why not? I’m the one making it.”

“I can’t, as a white woman, take a quilt called For Trayvon from the Black family of the artist, and put it on my wall.”

“It’s called For Trayvon comma Blues.”

“And that makes all the difference.”

“It makes a certain amount of difference, yes. You’re a singer. She loved that you were a singer. She would want you to have something of hers. I don’t know, Carrie, fucking figure it out yourself. I’m giving it to you. It’s a trade. I need Study back in one week or I’m going to sue you.”

“Am I allowed to sell it? The Trayvon quilt?”

“Are you serious?”

“Have you been to Hudson, ever? People are just going to look at it and think, oh, what a pretty polka-dotted quilt, that’s some great folk art.”

“Sounds like you need some new friends.”

“I’m forty-nine. I have all the friends I’m ever going to have. From this point on I’ll only make new friends at Pilates.”

“It’s not my job to fix your life,” Moni says.

“This is unbearable,” Carrie says. “It’s kitsch. It’s gross. This isn’t what I came here for.”

“It doesn’t matter what you came here for,” Moni says. “And if we’re reduced to kitsch, it’s not by accident.”

“I don’t understand what that means.”

“Kitsch is what exploitation does to people.”

“Oh, give me a break.”

“If you don’t take it,” Moni says, “I have to destroy it. It’s stipulated in the will. All unfinished work has to be burned or shredded. I’d be doing you a gigantic favor and putting myself in legal jeopardy.”

“You’re lying.”

“You know what she was like.”

I do know what she was like, Carrie wants to say, and I know that she wanted me to have something of hers to keep, one of the real ones, the ones I saw alive in her hands, even if she didn’t put me in the will. Why would she put me in the will? She knew what my house was like. She knew Carl. She thought I had everything I needed.

“We’re never going to see each other again, are we,” she says, reaching out a hand for coffee. “It’s like you staged it this way. You ambushed me.”

“I did not ambush you. Don’t be melodramatic, Carrie.”

“Then why do I feel like I’ve stepped into the perfect, I don’t know, vessel, container, for your condemnation? Why didn’t we just meet for coffee in New York, Moni? Because it wouldn’t seem so fraught. The world wouldn’t seem as small as it does right now.”

“I can’t help it if your world seems small,” Moni says. As if she’s taken too much DayQuil, or, as she did only once, a thousand years ago, in Ibiza, a knuckle-bump of cocaine, she feels spacey but entirely clear, the air a little too alive with reasons. “My world feels about the same size as always.”

“The key to bacon,” Kevin says, tongs in hand, “is to get a rack high enough so it doesn’t swim in its own fat. It’s actually healthier than people think, if you cook it long enough. Lean bacon. The flavor-to-calorie ratio is higher than any other meat. You just have to drain it and drain it again.”

Slices of French toast hissing on the griddle. Thin-sliced cantaloupe. “The grocery store was open early,” he says, Moni descending the stairs. “I had a helper. That was after we went for a jog.”

“He told me all about lactic acid buildup.”

“He’s good like that,” she says to Georgia. “Exercise physiology. Before I met him, I didn’t even know that was a thing.”

“So where’s Mom?”

“Packing. You guys have to get started soon.”

“She has to get back for a showing. I could just stay with you guys. Drop me at Grand Central when you get back to the city.”

“Very funny.”

“Why is that funny?”

“Because nine-year-olds can’t ride the train alone,” Kevin says. “Now eat.”

She gives Kevin a squint and a scowl, and slams the door on the way to the porch, though the morning is sullen and dim.

“And?”

“She’ll give it back. I guess.”

“You told her about Trayvon?”

“She won’t take it. She said, and I quote, ‘I’m done with this entire fucking nightmare.’”

“White tears. Not your problem.”

“You didn’t have to be an asshole about it,” Moni says. “You made this whole process harder. She’s still my friend. She’s in a difficult position.”

“She’s in no position at all,” he says. “She’s washed her hands. As it should be. I respect that. A clean slate.”

She’s pouring herself a second cup of coffee, automatically, not really listening. The question is why make art in the first place. Something she’s never wanted to admit she never entirely understood. The quilts, she wants to say, are an extension of Miss May’s personality, her privacy. How could you ever understand them otherwise? They have nothing external in them. Why try to sell something like that, why make it into a living? That was never an allowable question. A quilt makes a good gift, a keepsake for a baby, an index of relating. Why shouldn’t Carrie be allowed to keep hers? A commodity, she hears herself saying in the classroom, at the whiteboard, is a severed relationship, an act of estrangement, which to some of us—you’d be surprised how many of us—is our only allowable illusion of freedom—

Or something.

“You moron,” she says, hearing him now. “‘A clean slate’? Did you go to college? Have you read any of the books I’ve given you?”

“I was lucky to be alive in a less cynical age,” Carrie tells Georgia, on the exit ramp back to 95 in Delaware, “or maybe a less woke age, when people were slightly more willing to give you the benefit of the doubt, without this hair-trigger suspicion of your every move and motive.” Georgia, she can see in the rearview, isn’t listening at all; she’s engrossed in Lumberjanes. They do this all the time. When she needs to rant, she rants. “She never even asked me about access to the correspondence. That’s forty years of letters between an artist and her gallery. How’s anyone supposed to write a biography without that material? And what am I supposed to do, pay to keep it in storage forever?”

“I don’t understand why I had to leave,” Georgia says, not looking up. “It’s not like I have any reason to be back in stupid Hudson on a Saturday.”

“Matricia’s mom asked about a playdate.”

“I can’t stand Matricia. She’s lost her mind to BTS.”

“I am also a victim,” Carrie says. “I know she doesn’t want to acknowledge that. I’m not saying I’m the primary victim. Just that I was legitimately betrayed and traumatized too, and very, very, alone. No one was there to support me. I had to do those interviews alone. I had to apologize for him. And I think I acquitted myself pretty damn well, thank you very much.”

“But you couldn’t apologize to her.”

“To whom, babe?”

“Miss May, of course. You couldn’t apologize to her. She was dead.”

“I don’t get it.”

“Maybe that’s the whole problem,” Georgia says. “The dead people are the ones who deserve the apologies, and they can’t get them.”

“I honestly thought I would feel a sense of relief,” Carrie says. “After this weekend. I honestly thought we’d come to some kind of understanding, and, like, sign a sheet of paper or something. I thought that’s what Moni wanted. You did this, and now you don’t have to do anything more. Instead it’s like this fog that settles over everything and just sticks to you, like you’re always going to turn the corner and somebody’s going to accuse you of something.”

“You didn’t do anything wrong, Mom.”

“My intentions were good,” she says. “They were balanced. I was trying to think holistically.”

“Then you did your best,” Georgia says, wearily, repeating something she’s heard a thousand times. As if to say: Can we talk about something else, or nothing? “All you can do is your best.”

A woman running in the rain, carrying a guitar. Running up a gravel driveway, her sneakers half-slid-on. Holding up the guitar in both hands, as if to keep it out of high water. A woman in a long Carolina Panthers T-shirt and running shorts. Rain streaming across her forehead. The steel glints of droplets on the face and neck of the guitar, and the white car nearly out of sight. In one way of telling the story, a girl’s face appears in the back window, though in another, she already has her headphones on, the Kindle cradled between her knees. A guitar older than any person now alive on the Eastern Shore of Maryland. A guitar older than recorded music. A guitar that has been out in the rain before. Please don’t go. Go, go, please don’t go. A guitar hanging on the wall in the first act has to go off by the end. If this story was told in molecules, the way God meant it, there would be no story. The white rectangle would never get closer or farther away. The branch in the road would be an accidental, a worn brown thread hanging off like a tell-tale on a sail. It doesn’t matter that entropy carries things away from one another; they always return in some other form. The guitar flies up in the air when she trips, but she angles her body into a C, pivoting like a discus thrower, and it lands not on gravel but in a bed of ferns and sassafras shoots, plantain and dandelion, strange medicines. She brings her elbows together, crosses her wrists to shield her face. A woman’s body, stretched over the ground, reaching out to catch something or let it go.