Microscripts, by Robert Walser, translated by Susan Bernofsky. New Directions, $24.95

Born in Biel, Switzerland, in 1878, the writer Robert Walser lived until the age of seventy-eight, and through his work, letters, and personal associations came into contact with some of the major literary figures of his age, but the story of his life remains fragmentary, peppered with lacunae. Living in near-poverty and dressed in natty but threadbare suits, he cultivated few personal attachments and owned almost nothing. He courted several women and corresponded with others but never married. Like the rest of his siblings, he produced no children. In the last three decades of his life, confined to an asylum, he didn’t publish a word, if he even wrote at all. Yet despite this lack—what could be called an anti-legacy—Walser left behind a large body of work that uniquely fused the Romantics’ exultation in nature and search for the sublime with the early Modernists’ sense of play and intertextuality. But while the author was innovative in his work, Walser himself was an ethereal figure, divorced from time: an apolitical person in a period of great political upheaval; a barely educated wanderer who’s garnered the posthumous reputation of a hermit genius; a literary mystic miscast as blindly mad, when he in fact was all too aware of his own complicated demons.

Walser, who wrote in German, moved constantly, spending time in Berlin and Munich, and in dozens of different boarding houses and hotels throughout his native Switzerland. In one year, he moved twelve times. Suspicious of neighbors who sometimes thought him more crazy than eccentric, he was a restless soul who, in the Swiss tradition, enjoyed long walks, feeling that contact with the environment was healthy.

Walking was also a method of travel: in 1920, he journeyed more than seventy miles on foot from Biel to Zurich to give a reading with a literary group. After a rehearsal with Walser, the organization forced him to allow Hans Trog, a magazine editor, to read while the author watched from the crowd. The event represented one of many disappointments Walser would suffer at the hands of fellow writers, and it likely contributed to his eventual withdrawal from literary circles.

Because of his family’s worsening finances, Walser left school at fourteen. He briefly attempted to be an actor but gave up after a disastrous audition. Later, he found work in a brewery and as a butler in a chateau. His fallback profession was that of clerk or copyist, and he occupied such roles in a number of banks and offices. He published his first poems and prose in the last years of the nineteenth century. He spent 1905 to 1913 in Berlin, during which time he was enormously productive, publishing three novels, The Tanners, The Assistant, and Jakob von Guten, as well as collections of poetry and short prose. Many of his short pieces appeared in German-language newspapers and magazines. His work earned him the admiration and, occasionally, the professional assistance of Robert Musil, Christian Morgenstern, Hermann Hesse, Franz Kafka, Max Brod, and Walter Benjamin.

In 1913, his publishing fortunes waning and frustrated with Berlin’s stuffy intellectual scene (meeting Hugo von Hofmannsthal, Walser asked the Austrian writer, “Can’t you forget for a bit that you’re famous?”), Walser returned, defeated, to Switzerland, whose provincial environs he preferred. Then the troubles began. His father died in 1914. (His mother, whose depression and lack of affection were formative influences, had died in 1894.) That, of course, is also the year in which the cataclysm of World War I engulfed Europe, and Walser spent several weeks a year for the duration of the war in military service. In 1916, his brother Ernst, who had been in Waldau Mental Hospital since 1898, died; his brother Hermann took his own life three years later.

Walser entered a period of financial hardship and perpetual wandering, interrupted by stays in various rooming houses and a hospitalization for sciatica in 1924. (Later that year, he walked from Berne to Geneva, a distance of ninety miles.) Publishers rejected his novel Theodor; no copies of the manuscript remain, nor of another novel, a sort of sequel to The Tanners, that Walser destroyed. He wrote prolifically: feuilletons, fables, reconstituted myths, fairy tales, short stories, poems, dramolettes (brief plays), and other manner of literary sketches. But he found less and less of an audience for his work—popular tastes had changed in the post-war period, and Walser’s writing, despite his melancholy, had become too fanciful and playful. He began to drink excessively and attempted suicide.

After claiming that he heard voices and suffering a nervous breakdown in 1929, Walser voluntarily checked himself in to the Waldau sanatorium in Berne, the same facility that had housed his brother, Ernst. A diagnosis of schizophrenia followed, though the finding has since been heavily debated. In the early years of his hospitalization, he still wrote frequently and published some short prose. In 1933, he was transferred, legally but against his wishes, to a facility in Herisau, where he remained until his death in 1956. Allowed to take long walks, he always returned to the facility, where he also performed menial chores.

Sometime in the late 1920s, or possibly years earlier, he developed his peculiar “microscript” method of composition. In May, New Directions published a selection of these fascinating texts, translated by Susan Bernofsky, under the title Microscripts. But before considering these pieces, which fall into the diverse categories of short prose listed above, it’s important to examine the writing method itself.

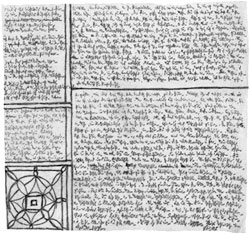

Walser called it his “pencil system” or “pencil method,” and it has also been described as “microscript” and “micrography.” Whatever the name, the writing technique entailed shrinking down letters to only 1 or 2 mm in height. Walser used Kurrent script, a medieval form of German writing that went out of fashion by the mid-twentieth century. The shrunken text allowed the writer to fit an entire short story on a business card, and he sometimes did so. In fact, he wrote on seemingly any available paper surface: postcards, telegrams, receipts, art paper, calendars, envelopes, and the torn-off covers of trashy novels (which he loved). Frequently he cut larger materials down into narrow strips, on which he then wrote.

To an observer—the New Directions book contains photocopies of its twenty-five transcribed microscripts—these appear to be either a secret code or indiscriminate scribbling. His long hospitalization only furthered the notion that these were the markings of a madman. But Carl Seelig, a writer who became close with Walser and took many walks with him in the latter years of his life, eventually published magnified copies of some microscripts in a literary magazine after Walser died. A man named Jochen Greven, then studying to be a literary scholar, managed to decipher the texts, but Seelig resisted Greven’s entreaties for access to more microscripts. Seelig, who had unsuccessfully tried to get Walser released from the hospital and had become his friend’s legal guardian and literary executor, was protective of Walser.

After Seelig died in 1962, the microscripts entered the hands of Werner Morland and Bernhard Echte. It took them more than ten years to decode the 526 pages of materials, yielding a startling omnibus work: titled From the Pencil Zone, the decoded microscripts span 2,000 pages and six volumes. There also emerged a full novel, The Robber, which had been written on twenty-four sheets of 13 cm by 21.5 cm art paper. The once-dismissed writings of a disturbed mind, now rehabilitated and growing in posthumous reputation, appear to be some of the most formally daring work of his long career.

Yet who would ever choose to write like this, in a scheme so deliberately recondite that it’s difficult for even the writer to read his own work? His alleged mental illness provides one handy explanation. Jürg Amann, who wrote a literary biography of Walser, has said that by condensing his writing into an impenetrable script, Walser took “the last step of disappearing”—a logical step in retreating from a world that had caused him numerous personal and professional disappointments. It’s an elegant comment, with some truth to it, but a fuller explanation is possible.

Using clues from the writer’s letters and fiction, Susan Bernofsky, in her introduction to Microscripts, convincingly argues that Walser was working on the microscript technique well before his hospitalization—possibly as early as 1902, when he wrote letters in tiny handwriting to his sisters. Bernofsky quotes a passage from The Tanners, published in 1907, in which the main character Simon cuts up paper into small strips and writes a long essay on them. Later, microscript became Walser’s de facto method for composing first drafts before copying and revising them in conventional handwriting.

Bernofsky raises a second compelling argument for the development of the microscript technique, centering on Walser’s mental state. In 1927, Walser wrote to editor Max Rycher, describing hand cramps that afflicted him when he attempted to write. The cramps, which Walser said had both mental and physical components, deprived him of his usual speed as a writer and of his ability to fill a page with beautiful script. Walser’s brother Karl was a noted painter, and Robert himself had some artistic ability, translating it into measured calligraphic handwriting. The pencil method, in its opacity, its continuous arrangement of slashes and strokes, created its own kind of visual harmony, while also encouraging play and free thinking. The result was a release of tension that, in Walser’s words, “revived my writerly enthusiasm.”

The pencil—that classic child’s tool, Bernofsky reminds us—was also physically easier to write with than a pen. By using it, Walser committed himself to a personal, hybrid language, one in which it was permissible to be himself, with his seemingly antiquated aesthetic tastes.

Years earlier, Walser had been offended when Thomas Mann described one of Walser’s novels, in terms of its level of imagination, as childlike. Not coincidentally does Walser say that in using the pencil, “I learned again, like a little boy, to write.” Christopher Middleton, another of Walser’s translators into English, has likened Walser’s childlike wonderment toward the world, and his “untutored” development as a writer, to the primitivism and “naïve art” movements then underway in the form of practitioners like Henri Rousseau. (Such movements also had their antecedents in nineteenth century Romanticism—another Walser influence—which fetishized indigenous art forms.) But any childlike character Walser may have had seems more like a method of escape from a tormented self than a concerted attraction to the markers of youth. Walser’s identity, if any, was predicated on self-abnegation, a gradual erasure: his characters desire nothing more than a small room to call their own and often comment that they are “zeros.” Reflecting on being in an asylum, the author told Seelig, “I am not here to write but to be mad.” Ironically, this vow of literary silence, a comment charged with disgust at an uncomprehending world, has become one of his most famous and quoted lines.

Consistent with this agnosticism regarding the very notion, or value, of a self, Walser switches to the third-person partway through his letter to Rycher: “he hideously, frightfully hated his pen . . . to free himself from this pen malaise he began to pencil-sketch, to scribble, fiddle about.” When Walser was using the pencil method, he was not fully himself. He was plumbing a space somewhere between automatic writing and traditional composition. It was a half-conscious effort, a way to escape his analytical self, his self-castigating mind, by tricking it into being loose, uncaring and to learn to write, to play, anew.

The word “transcribe” is often used to describe Morland and Echte’s work on the microscripts, but their job was far more complicated and painstaking than that, as Bernofsky well describes in her introduction. Using “thread counters”—a sort of jeweler’s loupe for those in the textile trade—they magnified the microscripts and attempted to decipher them. Even with the visual enhancement, some words were impossible to determine; others could only be guessed at.

For the non-German reader, the process of translation produces an additional layer of mediation on top of the transcribed text, whose accuracy, quite understandably, remains less than perfect. Susan Bernofsky is an esteemed German literature scholar and translator, having also translated Walser’s The Tanners, The Assistant, and The Robber. In Microscripts, she must contend with the author’s love of wordplay and neologism. Walser delights in mashing words together and creating nouns out of adjectives—a process for which German is well suited. The result is some peculiar English translations, perhaps not pleasant to pronounce but certainly in line with Walser’s mischievous style.

It’s a style that would be entirely lost to the non-German reader if not for Bernofsky’s ingenious translation, which finds or creates English equivalents for Walser’s nettlesome, idiosyncratic sentences. Take, for example, the story “A Sort of Cleopatra,” about a woman whose high opinion of herself leaves her loveless. In just half of one vertiginous sentence, Walser writes of “a girl growing up in a reformatory interlaced with principles—and therefore of necessity vigorously interlarded with rapscalities and the like—and constantly peering into life with its innumerable unfathomednesses or incalculabilities.” Pairing “interlaced” with “interlarded” and “rapscalities” with “incalculabilities,” marks a deliberate parallelism and a creative slant rhyme, craftily preserved here by Bernofsky. With the invention of “unfathomednesses,” Bernofsky finds a creative manner of representing, in a single baroque word, the notion of that which we cannot fathom.

This kind of writing can lead to plodding reading, and despite Bernofsky’s fine translation, some of Walser’s microscripts remain cryptic even after multiple passes. Some simply resemble free associative works, an outpouring of his various enthusiasms. Walser has a tendency to write for and of himself: he once said that “the novel I am constantly writing is always the same one, and it might be described as a variously sliced-up or torn-apart book of myself.” In Walser’s work, then, more than that of most writers, distinctions between genre or fact and fiction collapse, revealing an unfiltered voice, honest in its expressions. His frequently emotional aphorisms—offering his thoughts on the writer’s life, the meaning of freedom, even how to be a decent person—only enhance this notion that Walser married Romantic sensibilities, down to the predilection for rapturous nature walks, with an early Modernist style.

Walser’s book of himself should not be confused with self-absorption. If anything, his characters, even when they’re poets and writers, are, like himself, humble people, immune to self-seriousness, and open to experience and the thoughts of others. (The word has been whittled down into something trite, but one could say that he was a “dreamer.”) But there can be a sense, at times, that we’re not fully in on the conversation, despite the occasional aphorism or sly bit of address offered to the reader. In liberating himself with the pencil method, Walser became willing to wander off wherever the next impulse took him, at the expense of a coherent narrative. Even so, we are there with him, as Walser well knew, writing in “Autumn,” “It amuses me to believe that readers are, as it were, writers’ chaperones.”

Microscripts includes a short but wise essay by Walter Benjamin that partially explains some of the more bewildering pieces. (An editor’s note explains that Benjamin, ironically, began using his own microscript technique for note taking in the 1920s.) Benjamin coins a term that translates as “chaotic scatteredness”—an apt formulation for describing Walser’s verbal perambulations, his elaborate sentence structures that pile dependent clauses upon one another until the sentence threatens to collapse under the load. In Benjamin’s view, the reader must not try to unravel Walser’s wandering narratives or his feverish metaphors but rather enjoy a “seemingly quite unintentional, but attractive, even fascinating linguistic wilderness.”

Benjamin further writes that, “a torrent of words pours from him in which the point of every sentence is to make the reader forget the previous one.” Whether or not Benjamin correctly divines Walser’s intentions, the lesson is sound: best to appreciate Walser’s microscript stories for what they are. Some are pithy fictional sketches, clever pastiches, or recasting of ancient myths; others are word salads of sprinting thoughts that resemble prose poetry.

Walser himself may not have always known where his microscript pieces were headed. By his account, the pencil method lent itself to improvisation. He has a tendency to interrupt himself and address the reader directly, asking questions or making justifications for a particular line of investigation. A number of pieces end with some comically worded variation of “I think I’m done”—the “I think” is important to Walser’s unflagging modesty. He’s willing, if you consent, to pick up the threads again in the next fable or sketch and see where they lead.

And pick up he does. We often encounter similar character types—poets, clerks, wanderers, artists, people slightly out of step with society’s general pace—and recurrent motifs, such as laconic boat rides on lakes or slow walks that allow for a close examination of the landscape. He has sympathy for underdogs and for those who try to be just, like the medieval aristocratic, the subject of one microscript, who abandons his social class and throws in his lot with the rebellious townspeople, who in turn reject him. He ends up ashamed and disappears, abandoning his title and material wealth. Later, an “unnamed educator”—even he remains anonymous, without distinction—builds a small monument to the forgotten aristocrat.

The sixty-page story “The Walk,” found in the Selected Stories published by NYRB Classics, is far longer than most Walser short stories but revealing of his habits. Written in 1917, the story presents a protagonist, a writer, who seems oblivious to the carnage raging elsewhere in Europe, though his naïveté appears to be meant satirically. He jauntily compares war to art and writing, saying that writers are like generals and require similar preparation before launching into their battles. The writer also admits a “comprehensive, constant, and intense fear” of tailors and describes his dramatic and utterly absurd argument with an uppity tailor in martial terms: “I withdrew my troops from this unfortunate engagement, broke feebly off, and flew the field of shame.” Eventually he encounters a trainload of real soldiers “sworn and dedicated to serve their dearly beloved fatherland” but forgets them as soon as their train passes, instead reveling in his pastoral walk.

But this same man can be disarmingly self-aware, sneaking in revelations about the writer’s life. An argument with the local taxman turns into a fervent, profoundly eloquent explication of the urge to write and of the writer’s favored walks. The latter are, he explains, his way of observing the world and without them, “I would be dead, and my profession, which I love passionately, would be destroyed.” Because it is on walks that, “the lore of nature and the lore of the country are revealed, charming and graceful, to the sense and eyes of the observant walker.” Calling walking a spiritual endeavor, he says that the walker—and, by extension, the writer—“must be able to bow down and sink into the deepest and smallest everyday thing . . . Faithful, devoted self-effacement and self-surrender among objects, and zealous love for all phenomena and things, make him happy in this.” Here one remembers W. G. Sebald’s praising remark that Walser was “a clairvoyant of the small,” deeply attuned to life’s most insubstantial and fleeting beauties.

After three-and-a-half pages of such talk, the taxman responds, “Good!” and says that the request for lower taxes will be considered. It’s an abrupt comedown from the high-flying, secular ardor of the preceding soliloquy, but Walser never allows his characters to indulge themselves for long.

Much of Walser’s short prose falls into this messy but interlaced conversation, the “torn-apart book of” himself. He wrote out of his own experiences, particularly in his novels, and sometimes recapitulated the penny dreadfuls he read into microscript sketches. This small selection of microscripts shows Walser preoccupied with many of his persistent concerns but even more humbled later in life—less eager to cast stones than to get lost in his own hedge-maze of verdant language; to see, quite simply, what kind of fun can be had there. To that end, he wrote in a 1929 piece called “My Endeavors,” “I was experimenting with language, hoping that it contains an unknown livingness, the arousal of which is a joy.”

We have no record of any writings, microscript or otherwise, that Robert Walser may have made after 1933. (An attendant from the Herisau sanatorium claimed that Walser wrote frequently—in pencil—on small scraps of paper and loved crossword puzzles.) But until then his work remained vital and searching, though it was sometimes a victim, like its author, of an unruly wanderlust. Writing in 1926, in one of several pieces he composed about the German Romantic writer Clemens Brentano, Walser opined, “what a gentle and angry instrument I am.” Bernofsky’s translation lucidly balances this phrase on a fulcrum of two common adjectives; the result is an astonishing slip of poetry, signaling Walser’s complex self-awareness. Walser could be fierce—towards himself, towards his perceived antagonists, towards the paper scraps that he tore and scrawled upon—but he was also a bighearted thinker, an innovative stylist, and a creator of winsome verbal melodies.

1 Comments

wonderful piece, very informative wiyh some shrewd observations, thank you. Just discovered RW and read Berlin Stories which made me laugh, cry, wonder.... You're right, he was bighearted as well as brilliant. He deserved more success in his time but then we would not have had his belated resurrection to enjoy!