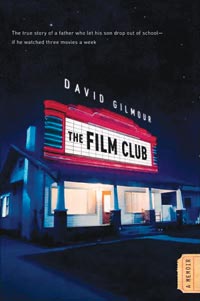

The Film Club, by David Gilmour. 12 Books, May 2008. $21.99

In 1980, the Academy Awards embarrassed itself (not for the first or the last time) when it ignored Paul Dooley’s performance in Breaking Away. Dooley, one of the best character actors alive, plays the father of a teen boy in Bloomington, Indiana, who is obsessed with cycling, and, by default, with Italy, cradle of expensive cycling gear and flashy racing teams. With just the right touch of impatience and self-reproach, Dooley presents the epitome of a gruff family man, the type who expresses his love through admonition and example. Indulging his child’s penchant for speaking to him in Italian is worthless; getting him to believe Sisyphus embodies the ideal work ethic is everything.

It is a rousing film and not just because of its set pieces of bicycle racing. There’s an exhilaration to be had watching this often unscrupulous and abrasive (if hilariously so) father shepherd his gentle, dreamy son to independence, to manhood. That small joy is accented when we realize, given the circumstances, how badly things could have otherwise turned out. The father is continually confounded by his son through the movie; he’s not entirely sure what to do with him. And despite the story’s good-natured atmosphere, there’s an air of inescapability from a dead-end, small-town life marked by teen marriages and fist fights, cultivated apathy and balled-up fear. What we get to witness, what the movie has to offer us, is how an otherwise unremarkable man does the remarkable: be a good father.

The difficulties and frustrations of trying to be a good father are similarly reflected in David Gilmour’s memoir, The Film Club. One moment, sitting across the kitchen table from his fifteen-year-old son, helping him with his Latin homework, Gilmour sees something in his boy—a fomenting frustration, a sullen withdrawal—that silences him. The middle-aged film critic has a flash of painful insight:

And suddenly—it was as unmistakable as the sound of a breaking window—

I understood that we had lost the school battle. I also knew in the same instant—knew it in my blood—that I was going to lose him over this stuff, that one of these days he was going to stand up across the table and say, ‘Where are my notes? I’ll tell you where my notes are. I shoved them up my ass. And if you don’t lay the fuck off of me, I’m going to shove them up yours.’ And then he’d be gone, slam, and that’d be that.

Gilmour heeds that paternal instinct and makes an impulsive offer to the boy: You can quit school if you want. Jesse, boyish despite his six-foot-four frame, is thrilled at the reprieve from boredom. After second-guessing his decision, but remaining clear-eyed to his son’s misery, Gilmour sets some conditions: You live with me—you don’t have to work, you don’t even have to pay rent—but you can never touch drugs. And you must watch three movies a week, of my choosing. It’s an offer no boy—and a few grown men—could refuse.

Like in a high-concept movie, The Film Club revs up its plot early and lets the action unfold. Gilmour, who is also a prize-winning Canadian novelist, describes how for three years or so he became a Scheherazade to his school-hating, gangsta-embracing son. Gilmour hopes that the more movies they watch together and discuss, the more opportunities he’ll have to keep Jesse from self-destructing.

There’s more here than the author relating a parenting stunt. The writing is gracefully conversational, but expertly composed. Notice the use of “breaking window” and “slam” in the passage above, how Gilmour conveys through them the clumsiness and miscalculations of teen boys. That attention to nuance is evident throughout the memoir, not only in the construction of the prose, but in the weighing of situations. Gilmour is well aware of how risky the plan is. He continuously agonizes about it:

Looking at him across the table, I found myself moving fitfully from one unhappy image to another. I saw him as an older man driving a taxi around town on a rainy night, the car stinking of marijuana, a tabloid newspaper folded on the front seat beside him. I told him he could do whatever the hell he pleases; forget the rent, sleep all day. How cool a dad am I!

Yet he feels compelled to go through with it. He doesn’t know what else to do.

The first movie he shows Jesse is The 400 Blows, a choice he considers a no-brainer. Truffaut was a high school drop-out. He got into trouble with the authorities for minor mischief. The lead in the movie, Gilmour writes, ran away from a boarding school to audition for the part of Antoine. And the themes of the film—the wildness of youth, the desire to be free—have obvious parallels to his son’s situation. Does his son see himself in Antoine? “He thought about that for a few seconds. ‘No.’” And so it goes. Gilmour plays movie after movie for Jesse, from A Hard Day’s Night (the Beatles don’t do anything for him) and Basic Instinct (“You have to admit it, Dad—this is a great film”), to The Last Detail and Volcano: An Inquiry into the Life and Death of Malcolm Lowry. Some of them Jesse takes to, others he shrugs off with a comment or two, out of politeness to his father’s enthusiasm for them. Yet, as the hours crawl around the living room and out the door, each movie leaves behind a fine powder, a way of explaining the world. With each film, and each of Gilmour’s mini-lectures, a vocabulary for confronting his troubles silts up in Jesse’s mind, building up to a platform from which the boy can measure the world as it appears.

Gilmour clues us in at the beginning, and again halfway through the book, that, somehow, everything turns out okay, if not for the best. What keeps us interested is how he pulls off such a radical project, the kind that in poorer neighborhoods in the US might mean having your kids placed in foster care. (Gilmour—a prominent, well-educated white man living in Toronto—has a lot more leeway than most in what he can do for his son. That’s no knock on him, just a rueful observation.)

As the memoir progresses, layers of assumptions about Gilmour fall in scraped curls, gathering around the reader’s feet. He’s not financially comfortable. His job hosting a documentary show is coming to an end, and with it, a lucrative career in television. A man in his fifties, he now has to hustle for any work he can get before his savings evaporate. (He even tries to sign up as a bike messenger but, as an older employee tells him, the boss isn’t likely to hire somebody his age.) As his lists of contacts dwindle and promising leads turn to ash, Gilmour gasps under the burden. “I sat down on the toilet seat and had a small, private weep. Here I’d let Jesse drop out of school, I’d promised to look after him, and now it turned out I couldn’t even look after myself. A bullshitter . . .”

His personal life isn’t tidy. He suffered under an older brother who terrorized him when he was young. The brother, a former track star and “frat king,” lives in the corner room of a boardinghouse and once traveled to San Francisco to join a cult. (The cult refused him, Gilmour writes. That’s partly how he wound up in the background of a scene for Dirty Harry.) He doesn’t see that “sad, sad” brother anymore, nor will he let him come around Jesse. And his amorous history bears a sloppy defeat or two. At one point, when Gilmour consoles a love-tormented Jesse, he can’t help but think of an “old heartbreak of my own; I lost twenty pounds in two weeks over her.” Such is the toll of young love, but the love wasn’t all that jeune. Jesse remembers how his father’s old love used to read to him. Gilmour remembers the pathetic specimen he turned into. “I thought of that awful spring, the sunlight too bright, me walking through the park like a skeleton, Jesse darting timid glances up at me. He said once, taking my hand, ‘You’re starting to feel better, aren’t you, Dad?’ This little ten-year-old boy looking after his father. Jesus.”

It is no wonder Gilmour frets about his film experiment. As the years roll into each other, and little progress seems to have been made, he must ask himself: How have I in any way helped my son navigate romantic heartbreak and callous lechery, drug-fueled despair and hip-hop loutishness? How could something good possibly come out of anything I’ve taught him?

The beauty of The Film Club is how an inauspicious situation veers from probable catastrophe to cherished normalcy. The lone reason is that Gilmour, despite it all, is an outstanding father. His faith in his son is awe-inspiring. (As is the support of Gilmour’s ex-wife, not to mention that of Gilmour’s present wife, a woman who worked like a dog to put herself through college, and, as Gilmour points out, was probably not too amused by his plan. For a man to have kept the love and friendship of such women, he must be doing something right.) He reads his boy masterfully, calibrating his tact in conversations, snipping the wires of contention before they lace into a fence between them. All the while, he avoids the true mark of a hipster dad: He does not try to become best friends with Jesse. If anything, he’s careful to maintain a proper distance, warning himself to avoid locker-room talk. (“That’s what his buddies [are] for.”)

Jesse is absorbing lessons, though it may not seem like it. He begins to understand the value of work, the point of an education, even the attraction of books. (Gilmour doesn’t imply movies can reach youth better than literature; he’s just keenly aware that his son hates to read. Still, by getting him to watch the documentary on Lowry, as well as referencing Hemingway and Gide, he piques Jesse’s interest.)

As Gilmour hints at the start, the experiment turns out well. Jesse’s decency and resilience triumph over the seductions and betrayals of adolescence, and Gilmour comes to respect and admire his son. He’s blown away “at the fact of him,” and thinks to himself the words from the ending of one of his favorite movies, True Romance, where Patricia Arquette tells Christian Slater, “You’re so cool, you’re so cool, you’re so cool!”

Along the way, they forge a rare intimacy, punctuated by telling scenes: waking Jesse in the morning, sharing a croissant with him; sobbing with his son in the driveway, unable to salve his love-wounded heart. And the sublime moment—wandering through a heat-soaked Havana in the wee hours of the morning, having just pulled his son out of the clutches of a few hustlers looking to shake him down for money:

We followed a narrow cobblestone street east, the crumbling pastel apartment buildings rising on both sides, thick vines trailing down, a bright full moon shining overhead; no stars, just the single bright coin in the middle of a black sky. Night was at its peak. We came out into a square, a dirty-brown cathedral squatting at one end, a lighted café on the other, three or four tables sitting near the middle of the square. We sat down.

A waiter comes over to them, and they order ice-cold beers and Cuban cigars, enjoying them over quiet talk on the paradoxes of desire:

The sky had turned a dark, rich blue, a red bar running across the horizon. Such extraordinary beauty, I thought, all over the world. Is it, I had to wonder, because there was a God or was it simply how millions and millions and millions of years of absolute randomness looked? Or is this simply the stuff you think about when you’re happy at four o’clock in the morning?

Near the end of Breaking Away, the father is eating pizza behind the wheel of a car on his used lot. The radio is on. He’s listening to his son compete in a bike race at Indiana University—a race where he and his three buddies are the only townie team. As the announcer gives the play-by-play of the son—the sometimes ridiculous, but honest and passionate son—blasting his way to the lead, Paul Dooley, grinning, cheering, grabs the steering wheel, wrenching it right and left, back and forth, a good father revealing his pride in his son: “You’re so cool, you’re so cool, you’re so cool!”