I have sung the dominion of Jove, lifting my lyre to deal with so weighty a subject: the fall of the Giants, the bolts hurled victorious down on the fields of Phlegraea! But now the task of my lyre requires a lighter touch as I sing of young boys whom the gods have desired, and of girls seized by forbidden and blameworthy passions.

—Ovid

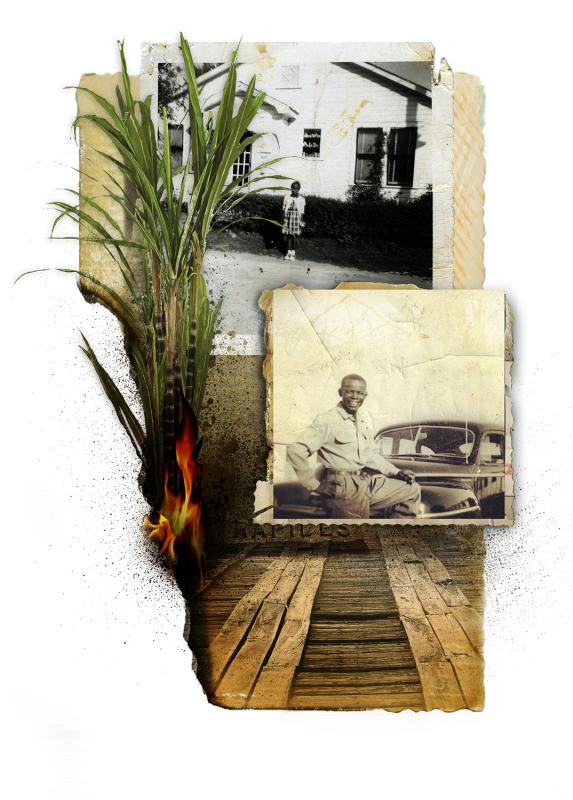

Lou Marie, my grandmother, is telling this story. It is a story about before, before she was old, before she became the drawl, the accent, the presence behind the white door in her own daughter’s house, with only her hair to keep her from looking like a heap of almost defeated life, long ebony hair styled by her own hands to look like Veronica Lake’s. Hair slicked into waves with VO5 and bergamot grease, by fingers with chipped red nails filed to a point, always hidden behind a constant billow of cigarette smoke. Still big breasted but now with missing teeth due to a diet of candy kept in thin plastic bags and warm Coke or cold Sanka sipped from a twenty-four-ounce plastic mug. She is my grandmother, but also forever the daughter of a “Chinaman” and an educated Negress from Baton Rouge. She stays to herself, alone in the end—married eight times but still alone, and afraid of the quiet, uneasy moment that occurs each day right before dawn when she can feel herself turning old and she is scared of the day, scared of the way dim lighting and high cheekbones can less and less hide the wrinkles and the wearing of age. Her arms so weak and so stiff making it more and more impossible that she will ever be able to gather the sediment that is routinely left after many broken hearts and pick herself back up like young people do, so like old people do my grandmother keeps stories about before in trunks under padlock. They are secrets scribbled in the margins of a Bible. My grandmother wants to tell me this story so it drives, so I listen and stop thinking I know it already. This is her correction, because they don’t teach you nothing in those schools, except lies and that we were weak, she says. And she tells it like she is losing her breath, like time won’t grant her the seconds to speak it. Such strange things can trigger her into talking, dreams about her stillborn twin, the scent of Chantilly perfume or damp days in mid-October, when lightning cracks and she wants us to cut the lights and be still. Only then does she want to tell about the beginning, about the baddest people who ever walked the Earth, and on those days I might sit at the foot of her mattress and stick my fingers into the orange, green, and brown frayed knots of her afghan blanket and listen:

When Robert E. Lee Sanders left town, everybody gossiped that he didn’t leave a note for me or send a message by his sisters or nothing, but in truth there wouldn’t have been much of a need to, because it was pretty much impossible that I wouldn’t find out about him and the mess he had stirred up way out there in the wood, on Cou Rouge Bridge, a bridge that wasn’t really much of a bridge, just some pine planks waxed with resin that he and his brothers had placed down side by side as means to cross the bayou without having to get waist deep in water and having to question if every log was a gator, if every ripple was a water moccasin, and it was a slapdash bridge, but it was very necessary because not a single person in the Sanders family knew how to swim, and that was an ignorance that had almost deaded them straight up when the Red River flooded Pine-ville in 1922, and it was only by the skin of their teeth that they got out then, Robert—I call him Bob—was just a baby, and if Sarah, his mother, didn’t have the mother-love-type determination like that of Sarah in the good book, Bob would have been dead or gone—that was the flood people wrote books about and men took to fishing for big-mouth bass by hanging rods out their living-room windows, he never did have any luck with water or white men, and so I suppose it is fitting that those were the two things that made him pack his suitcase and never look back—

Hmm, I remember the day he left, the same way I remember when he first started coming around Alexandria driving slow in his father’s truck and stopping at my house to ask after May Garvey, who was staying with Momma and me then, he was asking about May, but he only had eyes for me—buggy, nervous-looking eyes—not that I blame him, because he knew exactly what the deal was, knew who my mother was, Mrs. Arsan, there was no way he couldn’t know, because every colored child who went past grade school had to suffer her passion for diagramming sentences, and they knew if they acted up in her presence they would be clapping erasers, she was the principal and used that title to act as pious and stay as pure as the day she was born, but Momma wasn’t stuck on herself, hardly the kind to judge a person using a paper bag or because they had a French last name they couldn’t even pronounce, no, Momma was too concerned with progress, uplifting the people, but progress as it could be read in the Chicago Defender and the Pittsburgh Courier, the weeklies she read every night while she smoked her single indulgence—cigarillos—and mended what needed to be mended or graded papers before retiring, naw, Momma wasn’t checking for the type of progress Robert E. Lee was trying to bring, so while she respected the Sanders people, because it was hard not to—they were book poor but they were land rich, 187 acres rich—Momma knew the difference between Negroes and niggers, and I remember the day she came home shaking her head and talking about the boy just enrolled at the school, a boy who was most unfortunately named Robert E. Lee, and she went off ’bout how some folks didn’t seem to realize that being colored was a hard-enough burden to bear without a remorselessly foolish name attached to you, and I listened because with Momma there weren’t really many other roles to play, but as I sat there listening I thought about what type of boy would boldly go around giving that name, all of it, right down to the E, an initial that didn’t stand for anything but an initial, well what type of boy, so Bob would later say that he fell in love with me the day he came by to pick up May and he saw me listening to Louella Parsons’s Hollywood Hotel on the front porch, but I find that hard to believe because I recall that my hair was in paper-bag curlers, slicked into parts with the bergamot grease (Momma insisted I use as a means to stimulate my roots), and I was wearing my old, beat-up Buster Brown oxfords, so I find it hard to believe he was taken with me then, but I must acknowledge that nothing is impossible, especially since I fell in love with him the day Momma came home talking about a short, jet-black boy with legs like sticks and a chest like a barrel, all inflated and poked out, proud to be named after General Robert E. Lee but seemingly unaware that Lee was on the wrong side and Lee was not a black boy, and certainly not one from Lecompte, a parish that was the home of no-accounts and free folks who did nothing except what they wanted to do, and also home to Robert—

Robert, my love for him grew like the kudzuthat veils the trees back home until they look like brides—the image of him, a proud boy, rooted itself to my earth, between my legs, and centered itself between my chest—I could not shake it, like kudzu it was impossible to remove and cutting the vines and leaves don’t do no good, it persists especially if you cannot kill the runners and the crown, so my love grew like that and he never even knew, but how could he, seeing how we came from two different worlds: He lived with his blood beyond the bridge, in the wilderness that his people had shared with a few other families, them free people, the Williamses, and those raggedy LaCoeurs, who swore that they were Choctaw, but most of us knew they weren’t nothing but reckless black folks with a penchant for wearing their hair fried, dyed, and laid to the side, all them together lived out there in a clearing that they made by razing and burning a neat circle, a place you hardly could see for all the Florida maples and their leaves catching the light and making the world seem forged of copper and red lace, and they kept a big, old thicket of Red River maples packed close around a whiskey house, because if you didn’t know your way you were sure to get lost or be found out, especially if you didn’t have no business being out there, but I shouldn’t talk because I was one of those folks who fell in love with those woods, I wanted something new, gleaming, and private, so I found it, aware that Robert was “wild” and it was a breed of wildness I wanted and had ever since I could remember (at church the other ladies saw it and called it fast, because I liked to search for stares from men who were not staring and hunt down affections that weren’t obvious or easy), so when Robert came around I decided to recognize Providence answering my prayers, even though he thought I wasn’t like the girls he was used to, girls who caught their monthly blood in cotton wrapped in used newspaper, girls who would lie to their mothers about going to help the Sanderses collect corn for the mash and then go to the plush of the alfalfa fields with Robert and their coffle of siblings to keep watch while the two of them did the do, the bottoms of their feet arched, legs akimbo, and their backs curved to ride delight, brown girls with breasts the color and size of plums, plums that have almost turned, a few days away from spilling too-sweet syrup from skin in bloom—

Robert was used to that, so the moment he came around to pick up May Garvey, who was staying with us while her momma was in the hospital, he saw possibility, that is to say, he saw me, and even though he was raggedy, his fade was not cut and there was the red mud of the Mississippi River splattered over his clothes like the mark of Cain, I saw love and hellfire, a chance to dissemble the routine of my life, a chance for badness that was worse than stealing Momma’s bourbon that she exclusively used to calm and quiet her toothaches, a chance better than cigarettes smoked under the magnolia (to hide the smell), and so we set a date to meet, at the movie theater, the place I could go alone because Mr. Semmes always let me and Daddy sit in better seats, but once told Momma, on account of her color, she had to sit apart with “her people,” and ever since then she had taken a dislike to the pictures, that was the place where I could count on her never catching me in an untruth, that whole week I waited, and when the day came I set off on my bicycle and worried that my mother could see the way my heart was exploding like a morning glory at sunrise—

Robert was there waiting when I got there, he had his rusted-over pickup but I swear he looked like a Nicholas brother that could tap all over my heart and into heaven without breaking a sweat, you better believe, he looked good, and he said, Hey, hey little rebel, like he knew what I had in mind, and maybe he did, because I couldn’t hide my sweat, I never have been able to, then or now, and that day I sweated like a stuck pig, I had to fan myself with my empty candy box, and when he went for my hand, I pulled it anyway, on account of it being as wet and as limp as a dish towel, I was such a mess when the picture was over, Robert even asked if I ever wanted to see him again, because what else could it mean, my coldness, but of course I wanted to see him again, I wanted to see him until tomorrow ended, which caused him to suggest that we meet there again next week but skip the movie, so when next week came around I went to the theater which was near the old Bentley Hotel, and hid on a side street where they dumped the trash and compost from the dining room, and I waited for what felt like hours, wondering what I was doing hiding in alleys, like a lady of the night, making shame for my momma, and for myself, except nothing about it felt shameful, not the tingling, not the nervousness, nor the smile that just wouldn’t stop, it all felt natural, and when Robert pulled up I went with him without regret, and when I got in the truck we drove, and I didn’t ask once where we were going, I just talked, talked out my nerves, I told him about my daddy and how he died, about how much I missed him, about how from the top of his store we used to go out and watch the Easter parades and have the best view in town, I told him about the organza dresses my father made for me that beat any department store, his Chinaman eye for detail at work, and I told him about the time we saw two men get in an accident, one colored, one white, and the wooden steering wheel—they were all made of wood then—cracked and went straight into the colored man’s gut, but when the doctor was called he treated the white man for his concussion and ignored the dying man, so with nothing he could do my daddy held his hand until his moment came, and after I told him that, I couldn’t figure out why I told him that at all but now I think I said it so he would know I took after my daddy and didn’t see things exactly like my momma, and he listened, every once in a while taking his eyes off the road to show me he was paying attention—

I talked like that until he got to the levee, where he parked and pulled a dirty satchel from under his seat, but not before he leaned over and popped my door open, and said, After you, and even though I knew my mother would kill me, if I got my shoes dirty or ripped my only pair of stockings, as expensive as they were, silk and everything, I pushed myself up on that levee and sat down right beside him, out of that satchel he pulled out a box of broken cookies from Shipley’s Bakery, what we used to call Frookies, and a strange bottle with strange symbols and stars printed all over it, so of course I asked him, What you brought me up here to do, you plan on poisoning me, and he laughed hard at that, but told me it was the wine that Mr. Behrman drank on Friday nights, and with as much nice stuff as Mr. Behrman had and seeing he was more dignified than the rest of the white folks, Robert had decided the wine had to be good, too, and had gotten some for himself, but what I couldn’t understand was how he even knew what Mr. Behrman and them drank anyway, well, it turned out and of course, Robert, he was ashamed at first, but I got it out of him, that sometimes at night, he would drive into town and park his truck and walk to the Garden District, where the white folks lived, and creep around looking in their windows, he’d finger their linens hung out to dry, and smell the curdled funk of their dirty clothes set out for the wash, he would look into their garages, he would drink from their just-delivered milk, so the way how some men gamble, some men go to titty bars, this was Robert E. Lee’s vice and it was a vice for two reasons—if he got caught, no excuse would save him, and second, there was no point to it—I told him he had better cut that junk out, but you know what he told me, So you think there ain’t no point to seeing what you can’t have, girl, don’t you know that there ain’t no hill for a high stepper, but that didn’t make no sense to me, so I changed the subject because it was making both of us upset, instead we talked about the parties the Cajuns had on their houseboats during the Spring Fiesta, and the pictures we wanted to go to, and I told him about my classes, and he told me about the fighting roosters he raised and how much money he got taking bets on them, and we drank that wine, which tasted so sweet you had to wag your tongue after each sip, almost as thick as cane syrup, and all that wine turned to laughter, and that was when I started to think that the same way I saw him, he saw me, not the girl with the chinky eyes like all the other kids called me or Mrs. Arsan’s girl, but me, and that made hunger for him like nothing I had ever known of—

After that Robert and I started getting familiar regularly, so by the time he took off, which was five months to the date after we first started to see each other, I had already stopped getting my monthly and was getting some weight in my stomach, so shock wasn’t even the word for what I felt when I heard from almost everyone and their mother what happened over on Cou Rouge Bridge, how his boy, Argus, had kept watch of no sort and instead had run lickety-split into the brush the moment he smelled the hot gunpowder that had belched from the white fellow’s gun, and despite how I felt about Argus, I still asked him to tell me exactly what had happened, he said that Robert and him had heard footsteps toward the other side of the bridge, and when they had looked up from their fishing they saw a face browned and sunned to the point it looked like patina fixed under a straw hat, it was a white man with shoestring-thin lips and tired, washed-out eyes that were no color and every color at once, although he was small in stature, he had a great gut that hung low over his denims and pushed through his shirt of the same fabric, a gut that slouched toward the ground like it was familiar with residing there, and as the man approached they realized it was Elmo Jerrier, a Yat-speaking piece of trash that’d moved from New Orleans to farm cotton that never grew, and raised dirty towheaded kids that would grow constantly, and each inch or foot they reached, the hungrier and more demanding they seemed to get, it was to the point now that he regarded them, his own children, as a collection of mouths in a row all lined up and agape, moving open and shut, always chewing and eyes begging in silence, and like any man who saw his own progeny like that, Elmo was driven to drink, to make thunder where there was no lightning, to create discord to disguise his despair, what an unblessed process of invention—he made himself into a drunk and rabble-rouser in a dumb attempt to be something other than trash, so Robert and Argus knowing all this recognized him and all that he stood for, but paid him no mind, they stayed sitting, wriggling their rods, eyes focused on their lures, two pieces of oak with holes bored into them that floated serenely on the water that was littered with pine rushes and the scaled shine that reflected off the backs of the whiskered catfish that moved along the bottom, nope, they didn’t even say anything when they could smell, hear, and feel Elmo’s hot breath that was little more than a cloud of alcohol, agitation, and unwash, hovering over them, instead they gave Elmo silence, sitting perfectly still, the three of them in total silence, until finally Elmo moved, he reached down slowly and gathered a handful of the chopped mullet that Robert and Argus had been using as bait, and with the blood and scales glistening in his hand, he said without pause, I’m going to count to ten and then you niggers better scat because I am of mind to fish today, and you gon’ let me to my thing, you hear, you hear, and then without warning Elmo squeezed his fist and let a hot custard of mullet innards come down over Argus’s head while at the same time expelling gas that sounded as loud as a bugle horn against their heads, Robert and Argus were ready to dash, but before they could Elmo changed his mind, because he had heard rumor that Sanderses were set to buy a car, a purchase that he could only imagine, so he said, You know what, skip that, skip passing, skip all that, you know what, I am in a mood to watch niggers walk on water since they seem prone these days to acting like they descended from the left hand of God and brought the jewels of heaven with them, and so what happened next, Robert himself told me, many years later, when it was all said and done for, that while he was sitting up there with the backs of his knees and his fingers clenching the wooden planks of the bridge, in case Elmo tried to push him or worse, he got to thinking, he thought about how he was grown, twenty-two, and yet he was still being told where he could take his leisure, which was not to speak of the fact that he was barely able to make out any sort of real livelihood, he thought about the board game his grandfather had described to him, an old board game his grandfather had played as a child with his master’s son, a game where the players raced around a board going from babies to old age, their speed and success determined by the choices they made, his grandfather had told him about the game in great detail, each year on the board had a title, for example twenty-two was the year of the duelist, once Robert had asked him why he loved it so, and the old man, whose eyes were so blind they looked like they had wet gauze wrapped around each eyeball, had told him, Of course I loved it, and I was good at it, too, I played to win, and of course you don’t know why, do you, and I suppose that in itself is a blessing, so let me tell you why, I played that game to win, because where else did I have dominion over my life, so that is what Robert thought about up on that bridge, and he looked to the sky blocking Elmo from his view, and he scanned the horizon, the thinned-out tops of the cypress, and in the distance, in one great moment, a pink cloud of roseate spoonbills set off out of the swamp, looking like a gift, and he laughed, and Elmo asked him what was funny, but he paid him no mind, so Elmo asked Argus, but Argus could only stammer and sweat, and say that he didn’t know, and that made Elmo mad, because a man down on his luck don’t like no jokes, he has no use for ’em, ’cause when he is feeling that low down he can’t tell if the joke ain’t really a joke about him, so Elmo, who was real low down on his luck, wasn’t having it, and Robert wasn’t helping things by sitting up there smirking like a nut, leaving Argus to explain what he honestly didn’t understand, and how could he, because as Robert later said himself, he was thinking about the strangest memory, the squares on the board that his grandfather had played in his childhood, one for each year, and twenty-two was the age of the duelist, the age where a man had to decide where he was going to go in life and he could either go two ways—to God or to the devil, to manhood or back to his momma’s breast—so sitting up on that bridge with the lures’ eyes looking like two gator eyes or some gator’s eyes looking like two lures—

Robert heard the click of Elmo’s gun, and heard him say, Jump, or you aren’t gonna walk off of this bridge, and that was when he decided he wasn’t gonna choose, he was not only going to walk off the bridge, he was going to also walk out of those woods, he was going to leave for forever, because he was finally aware that his mouth and pride were too big and his anger too white-hot for a black boy, and as he saw it any way he looked at it he could die either by Elmo’s shot or by not knowing how to swim, and those weren’t acceptable choices, so he watched the birds and had a sense that even if he left nothing behind, and even if he wasn’t a rich man, drowning because a piece of trash tried to scare you with they gun didn’t make any sense at all, so Robert lifted his hands in the air and scooted back and pushed himself up on his feet slowly, stood up, but nothing could be slow enough for Elmo, who started to yell for him to sit his behind back down, and Robert tried to talk sense to him, saying in a real low voice, Now Elmo you come out here, and we are sitting minding our business, not hurting nobody, and you come here threatening to throw lead, telling us to jump in the water, mad, what kinda sense does that make, you want two bodies on you before the day is out, think straight, you get out of our way and we will get out of your way and bygones will be like us, they’ll be gone, so whatchu say, Jerrier, but who knows what goes on in the heads of crazy men, still, I’m sure that made sense to Elmo, how could it not, but he probably didn’t want any sense that came from a black boy, so he pulled up his gun and cocked it and said, Sit down, but Robert didn’t because Elmo and his bullheadedness was just making him madder, so he started fussing, saying, What the hell, Jerrier, fuck, Jerrier, you know you’re just trying to scare us with your gun, that’s what this whole thing is about, so fine, fine, fine, we all know that every now and then a hobo looks in a trash can and pulls out a whole chicken, so if you think your bullets is faster than me then let ’em fly but they better fly, before you lose your whole stroke, and then he lunged forward and got one hand wrapped around Elmo’s wrist so hard it was turning red but he still wouldn’t drop the gun, so Robert kept squeezing his hand to the left and to the right, wrassling Elmo’s arm wildly, which made Argus think Robert had lost his mind and was a lost cause either which way, so he started sliding across from them as coolly as he could, dragging himself along like a dog trying to clean his self, that is what he looked like to Robert, who even though he was getting up in Elmo’s face he could see Argus out of the side of his eye, and he repeated himself, this time so close to Elmo’s face he could smell the rot of his breath, You think your bullets is faster than me, huh, huh, then let ’em fly, but as much as Elmo wrestled with him, and might have thought he was fighting no good itself, because Robert was dark and glistening, the veins on his muscles running like roads on a map of a dark world, Elmo didn’t squeeze the trigger, listen: You and I don’t know what flashes before a man in a fight like that, and as much people say it is his life, I differ, I’d say it is his death, he questions how he is gonna hit the six feet, how is it going to sound and what will be said about him when they speak about his soul, and Robert at twenty-two, with two ways to go, chose to follow the roads which, protruding from under his flesh, radiated from his chest, down his legs, and across his arms, the roads that were his veins—it was time to get the hell outta there, and he said later he thought of me all brand-new pregnant and the child that was growing in me, how would they think of their father, if he died up here, he grew sure that they would recall him by things worse than him being named Robert E. Lee, things worse than the fact he lived in the woods and on low land, because he knew there would be no way to explain to a child why their father didn’t fight for his life, no way to do that and even if you could explain it, even if you dared, the only way it would hold true would be to say that their father had believed, eaten, and swallowed whole the belief that he was lesser and had given up, and Robert E. Lee knew he was many things but he didn’t feel lesser, so he backed up and forced the gun into Elmo’s side and he squeezed and squeezed until he felt the kickback first and the sound next, his ears ringing, he dropped the gun at the same time as Elmo tilted forward and came down, like a chopped-down tupelo log, like the shot had sawed off his legs, and he coughed, big wet coughs of blood up onto his shirt, until he had a maroon bib around his neck, and when Robert could hear again he heard the rustle of the woods being parted and run through, the crashing of Argus through them, and he felt the hundreds of shaking pounds that was Elmo in his hands gurgling like a baby and doing what dead men do when they don’t want to die, trying to get one last use of all the things his body could do when he was alive, the cough was an attempt to shout, the piss coming down his leg was the last time he would feel that relief, and the shaking was meant to be his body running away, so Robert held him until he stopped and, taking him for dead, Robert turned Elmo’s body in his arms, until he was holding him up from behind his arms, and looking down on his face, his shattered brown teeth and cracked skin, Robert felt pity, or that is what he said, a pity for Elmo, his lips bubbling up spit and blood, his eyes so pale they looked colorless like those of a hog-dog or something unborn, so he held him and felt pity because Elmo didn’t know better, and now he was going to die for it, which is when Robert realized what he had done and he wanted to do what little he could to make it right, so he lowered Elmo down, gently as he could, didn’t throw him in the water or drop him without caring, because he knew that a bullet hurts the most when it gets moved around—so he did none of that, instead, Robert placed him down on the only place on the bridge where there were enough planks to prevent his body from falling through and disappearing into the soggy carpet of pennywort below, then he gathered his tackle box, a mason jar filled with hooks and moldy lures, and looking back once, he cut through the woods, the same way Argus had, avoiding the razed-out path, watching the good light of the evening as it dyed the sky, like she was trying on her different dresses, until she found the one that was dark enough to be the night—

Robert as he got close to his home, he was careful, there wasn’t no way he was gonna just run up on his house so soon after broad daylight, what if someone was watching, waiting on him, so he got down on his stomach on a mat of thrushes and nutria droppings, he listened to each noise, he knew the way a man’s footsteps would sound versus the soft scuttling of armadillos looking for supper, and he waited, sometimes half asleep, or sometimes awake praying he was asleep, but mostly he just waited for the rush that would be revenge and someone looking to do to him what he did to Elmo, but only silence came accompanied by the stars, then he heard her cry, and in the way that every child does, he knew his mother’s cry, the hard, choked cry of hers, Sarah, and when he heard it, he didn’t hesitate, he didn’t look twice, or think once, he heard it and took off like a shot dart, running in the wagon tracks, toward the apricot-colored cottage house his grandfather had built for them, the house his father was born in, the house he was born in and the house that as a child he had loved so much he imagined it to be a piece of fallen fruit from one of the trees they used to make wine, it was a dried clementine that had grown and grown until it was large enough to house an entire family but still hidden in the woods and forever safe, how else to explain its separateness from what lived across the way, as a child thinking his house was a satsuma he had hoped to eat one day and keep the seed in his stomach, so it would grow inside him and intertwine with his organs until he died, but now what of that remained, not a thing, and in his sprint to his house, he finally understood just how bad everything was, but he didn’t stop until he got to the steps and, taking them in twos, he strode across the porch, and was promptly stopped dead by the whack of a chair across his back, and while the pain tattooed his back, he saw his father holding his mother back, and she had seemed to age in the afternoon, her hair wild where it had once been pressed into a tight bun, skin wrinkled like bark, and his father, Freedman, shackled Sarah with both hands to keep her from throwing another chair, chairs that weighed at least thirty pounds and had been cut from trees that had taken three men to carry, that day fury did strange things to Sarah, it gave her muscle and she spoke even though she was a deaf-mute who hardly ever made a noise so as not to draw attention to herself, but that day Robert’s sisters Lula and Ina-Dee and them would later report to me that Sarah had spoken not just in English, but in what they thought had to be Russian or tongues, oh yeah, that day she spoke in languages the explorers don’t yet know, but that didn’t keep Robert from understanding, and she did all that talking until she fell down in a chair, and started stroking her forehead and her hairline, stopping to tug at the small tight curls that returned and unfurled like the swamp’s resurrection ferns, from all her sweat making her hair go back, until she had a two-textured halo of hair, and the rest of them, well, they all just stood there, because what was there to do but wait for certain death, but Sarah was not yet prepared to lose her son, not to no water or to some white men, so she pointed down, and Freedman pointed back and shrugged, he didn’t understand her, so she pointed again with more impatience and popped her neck, and then she circled her hand around Robert and Freedman and pointed to the cellar’s trapdoor and grunted one word everybody understood quite clearly: Go, Go, Go, she said, she pointed again, this time she drew her finger across her neck and spun her arms like a windmill, Go, she said, so they went on down, leaving Sarah in the very awkward position of having to lower them into the cellar with the peach preserves and pork rinds while she and her biggest, pitch-blackest daughters, Lula, Ina-Dee, and Bessie, waited on the porch on a bench with a shotgun behind them, kept much less than an arm’s reach away, waiting for things worse than haunts and ghosts but arriving in the same ghostly white sheets, men that would storm west over the bridge and across the bayou ready and loaded because her “boy” had shot at a white man, which is not to say Robert too didn’t feel awful, because when I heard it, I thought to myself, What kind of man leaves his mother to fend for herself, and before you think bad of him, too, you should’ve seen the woman, Sarah, she was tiny, but she was built like a fighter, her bitty features, very close together, nothing too big, too loose, caused them to, behind her back, call her Chief on account of her fierce face, because she was as bold as any Houma Chief there ever was—

Robert was worried but not too worried, because he knew whoever was gonna come was gonna need to bring the last days and its four horsemen to hurt anything his momma held close to her heart, but while that was all good and true, through the dark of that cellar, Robert could feel his father’s eyes glittering with disgust, staring him down, so instead he counted the spider crickets that clung to the moss-packed cracks in the walls in order to ignore those eyes, but his father spoke anyway, whispering, words carried on a sigh and he said, So where are you gonna go now, boy, ’cause I guess you know you can’t stay here, not anymore, not on my watch, and because Robert hadn’t thought that far, he said the first thing that came to his mind and the farthest place he could think of, and he said, I’m gonna go to Los Angeles, and out of the dark he got silence for an answer so he repeated himself twice, not because he thought he father didn’t hear him but because he didn’t even believe himself, and the whisper answered back, You gon’ take that girl with you, Lou Marie, or you ain’t thought that far yet, I suppose that is one more mess you were gonna leave in your wake, and even though Robert knew it made no sense to lie to a person who knew things that hadn’t been told or spoken of yet, he lied still, She ain’t no girl, she is my wife, the moment I get settled I am gonna send for her, but they both knew that was a wishful thinking and it made Robert upset, so he pulled a large, ugly cricket off the wall and stretched its hind legs straight while it played dead, and then his father spoke, So when you think that’ll be, weeks or years, but Robert didn’t know, how could he have, and his not knowing made him angry, so he talked back to his father, probably for the first time in his life, Come on now, man to man, you see me, you see what I’m in, and as it stands now I can’t get my mind around that yet, I’m sitting here, don’t know who is looking for me, or what they gonna do to me, and you asking me to speak on the motherfucking future, and you can see I can’t speak on no damn plans, but his father kept his cool because shouting wouldn’t have helped nobody, Watch how you talk, boy, don’t forget unlike them, I know where you live, fucker, and don’t you ever forget that I am your damn father and I coulda told you that plans are hard to speak on, especially when they haven’t been made, and especially when they haven’t been given an inch of thought, I really coulda told you that, not that you would ever think to ask, and not that I’ve never been as dumb or as hotheaded as you and tried to live my life by the seat of my pants and—but Robert cut him off and said, I’m not trying to be dumb, or live by the bottom my pants or whatever it is you think, old man, I’m just doing me, doing me the best I can, and he looked again into the emptiness that were his daddy’s eyes and his daddy looked into the dark that held his eyes, and whispered back to his son, Well, how does it feel now, MAN, and that was the last time they spoke that night, even though they slept down there, for at least enough hours for the sun to come up and shine enough dim light for Argus to sneak up to the house and tell Sarah and her girls (not Sarah, because remember her hearing had left her as a child, but she saw so well she fired a shot at his shadow that just barely missed him) that Elmo wasn’t dead as of yet, he would probably die soon but he wasn’t dead yet, and unless Robert wanted to join him he had better leave as fast as he can, so Sarah fixed him some corn bread soaked in buttermilk and the girls asked him to find the old German who lived down the road, who also had a car and owed his life to Sarah for caring for his lonely self one time when he had a fever that was so bad, he thought he was already melting in hell, go and tell him that they needed the favor repaid, and to come quick and to cut the motor when he got close—

Argus, who liked the urgency of an emergency,took that moment to seem like a hero and not like a scared fool, boldly kissed each of the girls on their cheeks like he was The Flash or something and set off, and Sarah let him because she was busy packing a bag for her only son, corn bread wrapped in newspaper, his maps, a jar of mulberry preserves, a dozen biscuits stuffed with bacon, a stolen golf ball he swore was lucky, some smoked redfish, three large jars of spicy pickled okra, a small tower of clean shirts, while Sarah got his clothes ready, one of the girls, Alma, most likely, snuck two bottles of homemade wine in there—

Bessie drew water for a bath, and Ina-Dee helped the men out the cellar and together they worked furiously to get Robert ready, and they had only just sat down to chicoried coffee when they heard a car coming, and Sarah could tell by their faces someone was out front so she took her gun and went outside and saw headlights flash twice in the distance and then turn off, and looking upward so tears wouldn’t fall she went back in and nodded at her son, and his daddy stated what they knew, It’s time, boy, Mr. Wise is here, and they liked to say they didn’t cry, because they could see Sarah just barely holding on, which caused his daddy to just shake Robert’s hand and say, Awrite, and following his lead the rest of them wanted to be brave so they hugged him goodbye like it was just one of those fancy trips white people take when they get tired of running the world, but Mr. Wise would tell my momma that Robert was wearing his Sunday best, a light blue muslin shirt that was so wet with tears by the time he reached the car it looked navy, after he got in and got situated, Mr. Wise told him he would take him as far as Lafayette and he would have to figure it from there, and Robert agreed for a split second and then said, Mr. Wise, I know I’m in no position to ask for any favors, but I got this girl over in the Alec, and she is carrying my child, and seeing as I don’t know when or if I will ever see her again, I hope it wouldn’t be too much to go by and tell her I’m sorry, and … but Robert was stammering and Mr. Wise, even though he lived alone out there, had no wife, no children we knew of, had a heart and that European sensibility where he saw folks as being somewhat equal, so he was more feeling than most folks back home, and so he nodded, and they backed up the road until they had room to turn around, and with the lights off they drove in, going ten miles per hour, until they got to our house at 205 Lowerline, where they stopped but didn’t kill the motor, Robert, no longer fearing my momma or anything, got out and went to my window and knocked, and laying in my bed, my hands over the low part of my belly I knew who it was, and I thought the baby, your mother, knew it, too, because she turned in my stomach, like she wanted to get out and meet her daddy a few months early, so I got up and put on the housecoat Momma had gotten me from Siegel and Goldfarber’s downtown and went to the window, and opened it and crying like a child he started to tell me what had gon’ down, but I was impatient, I had questions: What you mean, I asked him, you killed someone, you didn’t kill ’em but he’s gonna die, well, the second he does, they take you down in a lynching alley and make it right, you best believe it too, I had so many questions he couldn’t get a word in edgewise, so he let me exhaust myself and then he spoke:

Lou, ain’t nobody gonna lynch me, I’m going to Los Angeles, and I’m gonna do well, do well enough to send for you as soon as I can, and I’ll set us up in a house and nobody will enter that house unless they invited, ring the doorbell and wipe they feet before they come in, and if we don’t want ’em they won’t get no ordinary no, they’ll hear a hell no. And you will spend your days sitting out on your own lawn watching all those stars you love go by, shoot, you might get to know some of ’em and end up like Lena Horne or the like as pretty as you are. And nobody will call us no bad words and make us feel low down all the time, I’m done with this, no more, and Robert spoke, and spoke about the clothes he would wear and the cars he would buy, and as he spoke I just listened, and in my heart of course I knew it wasn’t true, Robert didn’t have no schooling or no stick-to-it-ness to make a plan and just a bag full of visions and eyes to see them with, which is what I had liked all along, how he didn’t see the harsh edges that wrapped around the world, so when he got done, I kissed him, and put my hands on each side of his face and held it, so I’d remember it better and when I got done, he took my hands and said, I don’t have no ring and I know how that looks, but I want you to know you are mine and I’m gonna send for you and make a good life for us if you wait, and acting like he had a ring he slid his fingers over my right ring finger, and he promised he’d wait, and I promised I’d wait, and then without turning around he walked backward to the car blowing me kisses, and as he walked away I saw that Robert wasn’t walking like a gangly joker no more, he stood a little taller and walked like his body was his possession, and so it was, he got to Lafayette and there he found a ride to New Orleans, so he worked there for a few weeks at a cotton storage depot until he saved enough to get to go west slowly, and every week or so he’d write and tell me just a bit more time and he would send for me soon, and finally he did, so I took that train out to Los Angeles hoping against hope that my dream for us was finally coming true, but when I got there no matter how hard he worked it seemed like a hand we couldn’t see kept pushing him down, preventing him from earning enough for all three of us, but we tried to be happy, we tried to hold each other up even though we were so poor that when I gave birth we couldn’t even afford a crib for the baby so I had to keep your mother in the chest of drawers, and then one day I looked at my baby and felt a kind of strength I never had before so I went to Robert and said that I wanted to take her home to see my mother but that we would come back soon, a week later Momma sent me money for a ticket and we took that long train ride back, back to the pines, back to Alexandria, from time to time I told him that we would come back to him but the time turned into months, and then it was years, and soon in order to even recall his face I had to look at our child, but whenever we spoke or wrote he would ask if I was waiting for him and I would say I was, even when I started seeing the man who would be my second husband, I still said it, because even though it makes you sad, to me it wasn’t a sad story, it wasn’t about us not working out or whatnot, or him being a no-good daddy or other people saying he had run off, that never mattered to me because I knew it wasn’t true, and even if it was the case it didn’t tell the whole story, what mattered most was what happened that day on the bridge, it made Robert into a man, and because he became a man he had to leave, and in his leaving, leaving me to raise a child alone, leaving me to explain to my mother that I was about to be a mother myself, leaving us open to the chatter and the gossip, he made me a woman, so that night as he stood in the small cut between our house and the neighbor’s next door, we promised each other lies because they were easier, and the moon looking like a smile shared my secret, that as the days passed she and I would both be getting bigger and rounder until we were full and completely ourselves.