I remember a great deal about what I liked to eat as a child. At age six, I was a big one for large bloody steaks; my parents called me “The Carnivore.” My favorite place was Lawry’s Steakhouse on Ontario Street in downtown Chicago. The proprietary sauce the restaurant bottled was also tasty and I sometimes shook it straight onto my spoon. At home, brown sugar out of the Domino box was good, as was the reconstituted lemon juice we kept in the refrigerator. (A babysitter told me that if I kept drinking it I would turn into a lemon, and, believing her, I stopped.) I can remember innumerable brands of sweets sold in the 1970s, wheedled from my mother at the supermarket or bought at the nearby convenience store with my fifteen-cents-a-week allowance. I loved candy necklaces with powdery disks you bit off the string, Chuckles and Pixy Stix, Cracker Jack and Good & Plenty, SweeTARTS and Smarties. I was skinny and a picky eater when it came to “real food”—chicken, potatoes, salad—but I liked what I liked. After a family trip to Mexico at age eleven, I fell for caramel flan and hunted it down wherever possible. I adored sugared donuts with jelly filling and the unbelievably rich cold milk from a local ranch that came out of the dispensers at the overnight camp I attended at age thirteen. Chocolate cordials with cherries and tangy syrup inside. Chocolate turtles—those confections with caramel and pecans. At the age of eleven or twelve I began cooking for myself and gravitated toward favorite recipes: eggs scrambled with melted butter and orange juice, sour-cream-and-scallion crepes, fudge, Tollhouse cookies. I felt a plunging distress when deprived of something yummy I’d counted on. Watermelon as a dessert after a camp cookout started a sad gray rainstorm inside my heart. So did the highly touted afternoon ice-cream snack at a different camp, when I discovered there was only ever vanilla. I did not care for vanilla.

I remember a great deal about what I liked to eat as a child. At age six, I was a big one for large bloody steaks; my parents called me “The Carnivore.” My favorite place was Lawry’s Steakhouse on Ontario Street in downtown Chicago. The proprietary sauce the restaurant bottled was also tasty and I sometimes shook it straight onto my spoon. At home, brown sugar out of the Domino box was good, as was the reconstituted lemon juice we kept in the refrigerator. (A babysitter told me that if I kept drinking it I would turn into a lemon, and, believing her, I stopped.) I can remember innumerable brands of sweets sold in the 1970s, wheedled from my mother at the supermarket or bought at the nearby convenience store with my fifteen-cents-a-week allowance. I loved candy necklaces with powdery disks you bit off the string, Chuckles and Pixy Stix, Cracker Jack and Good & Plenty, SweeTARTS and Smarties. I was skinny and a picky eater when it came to “real food”—chicken, potatoes, salad—but I liked what I liked. After a family trip to Mexico at age eleven, I fell for caramel flan and hunted it down wherever possible. I adored sugared donuts with jelly filling and the unbelievably rich cold milk from a local ranch that came out of the dispensers at the overnight camp I attended at age thirteen. Chocolate cordials with cherries and tangy syrup inside. Chocolate turtles—those confections with caramel and pecans. At the age of eleven or twelve I began cooking for myself and gravitated toward favorite recipes: eggs scrambled with melted butter and orange juice, sour-cream-and-scallion crepes, fudge, Tollhouse cookies. I felt a plunging distress when deprived of something yummy I’d counted on. Watermelon as a dessert after a camp cookout started a sad gray rainstorm inside my heart. So did the highly touted afternoon ice-cream snack at a different camp, when I discovered there was only ever vanilla. I did not care for vanilla.

By fourteen or fifteen my palate was getting more sophisticated. Chicken tempura. Homemade yogurt (my mother had bought a machine). Veal saltimbocca. French onion soup, very popular in 1978. My father and I shared a hankering for fine dining, and as a result I got taken to a couple of top-flight French restaurants, of which I mostly remember the rich sauces. Around this time it was common for girls at my school to talk about how they ate too much, what “pigs” they were for enjoying a large ice-cream sundae. I found this worry and remorse very strange. Food never made me feel guilty. The summer I turned sixteen I got to go to France for real, for a six-week stay with a family near the southeastern town of Annecy. Toward the end of the trip, two fellow American high-school students and I made an outing to a nationally celebrated restaurant. I ate until my stomach was painfully stretched and I was a bit nauseated. These were not bad feelings but the proof that I’d had a rarefied and cosmopolitan experience.

A couple of months later I was off to boarding school. I didn’t have early-morning classes so I slept late, missing breakfast, and made up for it with fabulously greasy donuts at the campus grill. I snuck chunks of York Peppermint Patties into my mouth from under the table in English, worried not about the indulgence but only about getting reprimanded for eating in class.

I can pinpoint the exact day that my eating disorder began, that all of this casual greed turned into something fraught and tormenting. It was February and I was at a classmate’s vacation house with my boyfriend and several of his friends. I was halfway through my sixteenth year. Someone had brought a chocolate cake; it might have been the host’s birthday. I must have had a piece. Afterward, I kept passing the cake where it sat on the kitchen counter, feeling a strong tug toward partaking again, and also a sense that I shouldn’t. I shaved small pieces from the edges. I picked at fallen chunks. I kept eating more. I don’t remember how much I actually ate, and that’s not what’s important. What’s important is that I was horrified at myself. Something new had happened; I had experienced a loss of control that frightened and disgusted me.

And just like that, eating became the focus of my existence. Thinking about food, weighing myself, deciding what I would eat or not eat that day, restricting, binging. (I was always worried that I would turn to vomiting, an act that I rightly believed would represent a further fall into compulsion and illness; fortunately I never did.) My weight had to be kept at exactly 100 pounds for my five-foot-one-inch frame. If I fell below that, I was too thin; above that, I was too fat. I had an absurd idea of how much food was enough to nourish me, and my undereating was offset by binges that brought on a depth of self-loathing almost impossible to describe.

Yet even when my disorder was at its worst, there were pleasures I can still recall. I considered it “okay” to eat when I was genuinely hungry. I don’t know if this was permission I’d received from Fat Is a Feminist Issue, a book I turned to which argued that compulsive eaters needed to reteach themselves to recognize their bodies’ hunger and saturation signals, or if I made allowances for this sanity all by myself. My definition of hunger was pretty stringent; I had to feel my stomach growling. But when that happened, even if it wasn’t yet mealtime, I could have—one Andes mint! One one-and-a-half-inch-by-three-quarter-inch chocolate wafer with mint filling. Absurd, I know; sad. But I did find it delicious. I ate it slowly, enjoying every bite.

The binges, too, involved pleasure, even if afterward there was disorientation and grief. I don’t recall exactly how things went at the beginning, but eventually I learned the art of the slow-mo binge. This usually involved a couple of megasized bags of peanut and regular M&Ms. I reclined on my dorm bed, reading a novel as I snaked them one or two or three at a time out of the bags. Again, they were delicious. And the eating could go on for hours. I was treating myself, experiencing the sensation of crackling coating and chocolatey mush over and over as each piece dissolved slowly on my tongue. Whatever sadness and anxiety had sent me here receded and I was safe for now, filled with a dreamy, horizonless peace. Eventually, faint with sugar toxicity, I could or had to stop. I would be sleepy and dopey and sometimes extremely thirsty for a couple of tall glasses of milk.

It was psychoanalysis that finally helped me put an end to the binging, if only indirectly. By my first year in college, I knew I needed help, not just for my eating but for my general misery and sense of psychic fragility, and my parents weren’t familiar with any other kind of therapy. They found me a referral to an older, white-bearded man who looked astonishingly and reassuringly like Freud himself in the photographs I’d seen. It was the real deal: lying on the couch, free association, three times a week. In psychoanalysis, my job was simply to lie there and say whatever came into my head, something that proved much harder than I’d imagined. At some point it occurred to me that coming to my sessions when I was binging regularly was no different than coming while strung out on drugs. How could I clearly see my thoughts and feelings when those thoughts and feelings were being numbed and suppressed by my eating behavior? I needed to get clean. I also suspected that if I did not get better I was only going to get worse, and I had nightmare visions of a hospital stay, with its infantilizations and deprivation of all freedoms, and the possibility of being at the mercy of unbenevolent caretakers.

So I stopped binging, by an act of will that so exhausted me at times that I skipped my classes and lay completely still in my dorm room, my ears stopped up with headphones playing a Kate Bush cassette tape on an endless loop, blocking out all other sensory input for hours at a stretch. In the meantime I forced myself to eat three regular meals and one nighttime snack.

It got easier, slowly. There was a long tail. I had to be very regimented in order to manage the temptation to both over- and undereat. Sometimes my concentration at the table was so intense, so taut, that I made other people, particularly those close to me, feel invisible; I had no excess energy to speak with or feel anything for them. I fell into dark moods when I could not eat what or when I wanted. I could be extremely demanding about the pleasures built into my food planning—I had to have this dessert, not that one, or I might weep with rage and anxiety. All this did not make me easy to be around. Even years later, my lingering eccentricities had to be obvious. At an editing job I held in my late twenties, each morning I brought in a small bottle of home-brewed coffee made precisely to my specifications; after lunch I extracted from the communal fridge an oversized bakery linzer cookie cut into eighths. I nursed one of those eighths and the coffee over the entire stretch of time remaining before my evening departure. This kind of parceling-out is classic eating-disorder behavior, yet I was reliably subclinical, because my weight was normal and stable, I wasn’t tormented by food and didn’t think about it all day, and I didn’t experience shame after I ate. I was weird about food, weirder than most of the women I spent my day around—although one never knows, maybe some of them had secrets. But somehow I’d made my system work for me. I experienced each bite and sip fully, the way the Buddhists say you should. I ate rigidly measured amounts but I also extended the amount of time I could enjoy them. I restricted pleasure, but I also indulged it. What was health, what was unhealth? Where was the line?

Food writer Betty Fussell’s memoir My Kitchen Wars uses an unapologetically erotic vocabulary for discussions of cooking and consumption. Like me, Fussell has vivid childhood food memories, including one of climbing into the family icebox and “finding within its coolness a big thick cube as golden as an orange and as smooth and velvety as ice cream. I took it out and licked it. It got slippery in my hands, creamed my mouth, melted on my tongue, and ran down my throat. By the time they found me, I had consumed the whole pound of it.” This was Fussell’s discovery of butter. She describes the “hurdle” involved in eating lobster—the forceful cracking open of the shell, the wresting of the flesh from the narrow spaces within—as being “as erotic to me as any porn flick.” Human beings have always known about the hurdle or the restriction and the way it increases pleasure. The corset, the dress that covers even the ankles, the veil. The irrationally expensive designer bag, the limited-edition print, the impossible-to-get table at the trendy restaurant. Dividing one’s cookie into eighths.

Someone could probably make a good argument that, over thirty years after I stopped binging, I still have an eating disorder. I could make that argument myself. I use food to cheer myself up, calm myself, energize myself, fend off boredom, tolerate being with others, tolerate being alone, tolerate writing, mark off sections of the day, have something to look forward to. This is true even though the amounts I eat and my weight (which I can go months without checking) have, except during my pregnancies, altered very little over the past twenty-five years. I hoard; it is very important to me that my pantry be filled with several types of carefully selected chocolate and at least a few cookie options, and I’m fierce about defending my stash from my teenaged children, who can polish off in two days what will last me many weeks. At some point during the day, I make a cup of tea and fill a saucer with ridiculously small treats: half a Milano cookie, a small chunk broken from a chocolate bar, one chocolate-covered mini-pretzel. I will nurse these along, sometimes with replenishments, over the next hours, before and after my main meals. I carry chocolate in my purse except in high summer, lest I be out longer than I expect or run into some situation that involves tedium and aggravation. I behave as if my emotional life is still as volatile as when I was eighteen or twenty; I still feel vulnerable to the sudden sweeping-in of despair with its existential questions, Where am I? What am I doing? Is it all right? Aimee Liu, in Gaining, a memoir about a recurrence of anorexic tendencies in her forties, suggests that eating disorders are rooted in temperament and are most characteristic of highly anxious types. I’ve come to believe this. I was an anxious kid and teenager, afraid of death and sports and driving and travel and groups of children and separations from my parents, and my dreams are still almost nightly filled with painful, depleting scenarios of missed bus stops, impossible-to-pack suitcases, unlearned stage lines, and college courses I am failing. If I’m not aware of being terribly anxious in my waking hours it’s because as an adult I have a great deal of control over my environment and have created a pleasant set of circumstances (self-employment; marriage; motherhood, which, in making me needed, made me less needy) that seems to keep anxiety quite nicely at bay. Usually. Especially when I have my chocolate to help me.

I love even more foods now than I used to, especially since I cook more regularly. My food pleasures used to be about the highest concentration of richness or sweetness, but now it can be about subtler smells and tastes and textures. I love vegetables with a bitter tinge—brussels sprouts, spinach, collard greens—and the dirty loaminess of mushrooms and the filling, nutty stickiness of rice. I love tender pieces of lettuce from the garden my husband maintains, and dense slices of bread toasted so dark that the surface almost caramelizes. I moan over a perfectly juicy peach, a tart, taut plum. I like the way a meal can turn out to have wonderful colors, like the lox-and-egg scramble I recently made that juxtaposed the yellow of an onion with the green of scallions and the red of a bell pepper. Food always looks more beautiful when I have cooked it myself. I love the bounty when my husband grills and our family table is filled with blackened chicken, a buttery slab of salmon, corn on the cob, a crusty baguette, a salad with gorgonzola bits and dried cranberries. I feel provided for. I like trying a new type of cookie for the first time, detecting its unfamiliar sweetness/bitterness and dryness/moistness ratios. I love the gluttonous feeling of eating quickly and almost thoughtlessly when I’m really hungry, my hand thrusting repeatedly into a bag of popcorn. I like the ghostly taste of jasmine in my tea.

Does the fact that I can reliably feel and give myself pleasure with food indicate health? If part of the pleasure is the pleasure of avoidance, does that reduce the health quotient? Regularly, in the middle of a weekend afternoon, I will feel tapped out from writing and/or talking to people and/or yoga class and/or chores and errands—if I lay in bed all day I would probably still feel tapped out—and sitting down with a cup of tea and plate of mouse-sized treats is a way to leave my life for half an hour, forty-five minutes. I invent a cone of silence around myself and try to radiate noli me tangere at my family. I know that what I’m doing involves magical thinking. I’ve found a way to believe that time has stopped, or will last forever. I’m escaping into a fantasy of safe isolation, a benevolent version of the complete alienation I felt while binging as a teenager.

Maybe pleasure and health don’t have any necessary relation. Maybe pleasure is clinically agnostic, though something in me resists that notion. The late Caroline Knapp wrote a book about her anorexia (Appetites), which she described in hellish terms, and her alcoholism (Drinking: A Love Story), which she found highly pleasurable, at least until it became clear it was destroying her life. Sex addicts presumably enjoy the orgasm. Maybe it’s elasticity that indicates health. I no longer have to stick to a rigid meal schedule, or tightly control what I eat and when. I can impulsively grab some salted nuts or a handful of chips and think nothing of it. I don’t worry about eating past my saturation point. I forget about food all the time: when I’m driving or talking with friends or working or just busy. I can even forget about food—I mean eating it, craving it—while I’m writing about it. But am I healthier the more I forget about food? Why would it be healthy not to think about something so strongly connected to nourishment and sensual satisfaction and ecology and sociability?

People who don’t have eating disorders often understand them to be purely about suffering rather than as behavior that involves an unpredictable pleasure/pain mix. A college boyfriend of mine wrote a work of fiction in which a stand-in for me was described as “always hungry.” Perhaps that’s what he believed of me, but it wasn’t my sense of things. It was no more true than that a person with an alcohol dependency is always thirsty. If I was hungry when he knew me, it was not in the physical sense of an aching stomach or muscles crying out for protein (I never became truly underweight) but in that I was chronically seeking the sensual satisfactions and the self-soothing that food offered. At the same time I was chronically afraid of overdoing those satisfactions, of cramming them into myself until pleasure turned to discomfort and disgust and—worst of all!—fat. Even with this hovering fear, however, I enjoyed eating. I loved food. I was perhaps exaggeratedly alive to its pleasures. A bag of buttered movie popcorn, a tall glass of Irish coffee with rich whipped cream on top, a big plate of fettucine alfredo—all could please me immensely, and I could feel satisfied and happy, or at least relieved of craving, when finished.

I’m willing to believe that for thoroughgoing “restricting anorexics”—the kind who never or almost never offset deprivation with bulimic binges—the act of eating may be so terrifying, and their body chemistry so altered by starvation, that swallowing food involves only revulsion. But restricting anorexics represent only one subset of eating-disorder sufferers, and even they are famous for loving to cook, loving to be around the look and feel and texture and smell of food, even if they will do so only, perversely, to feed others. Something of the pleasure still exists, even if displaced.

I’m also willing to believe that I’m unusual, or that I wasn’t really that sick if I could take pleasure in food even as I alternately overrestricted and overindulged in it. Or that it was my ability to maintain pleasure in eating that allowed me to become well again. Maybe. But can the world of eaters really be divided into the sick, who don’t know how to enjoy it, and the well, who do?

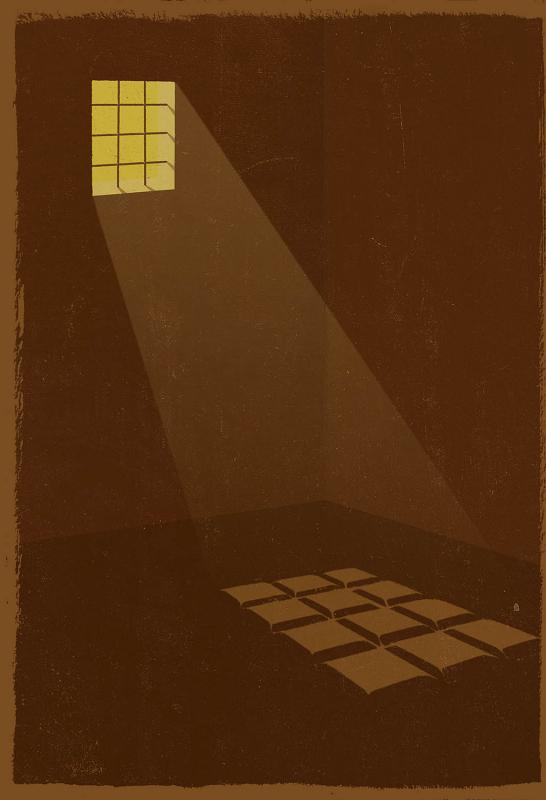

What is an eating disorder, anyway? Is it a relationship to food that makes a person experience her life as a prison cell? I could stand behind that definition. Is it something involving a restrictive and irrational dose of ritual? Most national cuisines could be said to do that. Is it eating behavior that is marked by lack of control? My control over my eating is much stronger and more reliable than my control over my writing habits and my sleep schedule and my commitment to exercise, and I don’t consider myself to have a writing or sleep or exercise disorder. I just consider myself a bit lazy.

Having insisted on how much pleasure food reliably offers, I must also acknowledge that it is still associated with pain for me, and not just in my memories of how awful things used to be. Growing up, I was the one in my family with the “bad stomach.” A meal too long delayed could cause terrible cramps, but sometimes they came on for no reason, and I spent many afternoons doubled over at my fifth-grade school desk. At fifty-one, I still have that unreliable belly, as well as a number of other “sensitivity” syndromes. I am the queen of the exclusionary diagnosis. I have joint flare-ups that behave like rheumatoid arthritis, even though I test negative for rheumatoid factor. For about ten years I’ve had a chronic cough. Everything scary has been ruled out, and my pulmonologist has finally settled on the term “reactive airway disease,” meaning my cough reflex is triggered by the most minor and invisible of irritations. And so with my GI system. I don’t have polyps or cancer or an ulcer or allergies; my stomach simply balks at much of what I put into it. There’s something comical and apt in the fact that I, the sensitive child upset by screen violence and rowdy classmates, who feared the least criticism from a teacher or friend, should have ended up with a body marked by its overreaction to everything.

There are times when I think I brought my surly digestion upon myself, with all those years of wacky eating. And times, too, when I think I maintain it with my elongated grazing. But those memories of fifth grade suggest I would have been dyspeptic no matter what. I’ve learned the reliable triggers, caffeine and dairy above all, and it helps to eat three sensibly spaced meals with no snacks in between. But here we are back in the borderlands of compulsion. I simply am not able to entirely forgo caffeine, nor my “nursing” snacks. When my stomach is steady, my desire for the gentle perk-up of coffee or tea, the tang of chocolate, grows more and more pesky. Abstinence begins to make me irritable and sad. To restore my cheer, I start with a few sips of tea, a little piece of sweet, and if pain doesn’t come, I indulge a little more the next day. This goes on until one day my belly rebels. If there’s a little pain, it makes me stop my grazing for a little while. If there’s a lot of pain—the kind that creates a tightness between my eyes and difficulty in concentrating—it makes me stop for longer. If I’m really unlucky, which happens two or three times a year, I may spend a couple of days in bed, because even walking hurts: It’s as if someone has beat up my large intestine with his bare fists. Whatever the case, I feel a shadow of what I used to back in college, that I did this to myself from a lack of self-control, that I can’t trust myself. It’s as if I still can’t abandon the language of shame and punishment when it comes to food, the sense of my life as a battle between what I should do and what I will.

It’s ridiculous to treat drinking a cup of caffeinated tea, or four sips of coffee, as a sin. This consumption may be ill-advised, in my case, but it’s not a sin. Besides, there is sometimes no clear correlation at all between what I eat and how my body reacts. I’ve gotten terrible pains after completely inoffensive meals. If I eliminated every food that has managed to upset my delicate constitution, I would starve to death.

I noticed something telling recently. Now that our national dietary conversation suggests that fats are no longer to be strenuously avoided, and sugar has been newly demonized, I find myself more attracted to sugary foods than previously. Before, my yen for sweets ran almost exclusively toward the bitter and sour tones. Dark chocolates, baked goods with a hint of lemon or raspberry or salt. Candy, no matter what kind, offered tastes too simple and cloying. Sugary cookies were bland and a waste of calories. I was looking for that rich mouth feel, that fat. But now that fat’s semiokay and sugar is not, sugary items call out to me newly as indulgences, as dietary luxuries. There’s clearly something in my nature that needs to feel tempted by what’s “wrong”—and likes to figure out how to get away with just enough of it. Occasionally I will eat or drink something I know is likely to trigger pains, which in fact come, and I’ll think: Well, I got three hours of writing out of that, at least!

In an interview Peter Matthiessen did with the New York Times Magazine shortly before his death last year, he spoke of an early, formative experience with Buddhist meditation: “The silence swelled with the intake of my breath into a Presence of vast benevolence of which I was a part. I felt ‘good,’ like a ‘good child,’ entirely safe. Wounds, ragged edges, hollow places were all gone, all had been healed.”

Perhaps it is a sign of a continued emotional adolescence that I still long, quite consciously, for such an epiphany, such an intuition of goodness in the world and in myself. Wounds, ragged edges, hollow places all healed! I practice Buddhist meditation (badly) and yoga (a little more consistently) in a humble search to inch closer to such possible enlightenment. But, do you know, a piece of chocolate can give me a simulacrum of it for a few moments. My heart settles, my breath calms, my concentration sharpens. I feel time slow and stop its harassments. Like Matthiessen I am safe and no longer gaping. Is it cheating, is it sickness, if this altered state comes from food and not a rigorous practice of mindfulness? My life does contain other, less embarrassing, vehicles of transcendence. One of them has been the love of my husband, which for years upon years continued to deeply surprise me and fill me with gratitude; now, spoiled by custom, I am less daily astonished but still grateful. The other is my love for my children. In their earliest months, the sense of completion and aliveness that they brought me was so enormous it was a new wound in itself. The reason was precisely that in experiencing completeness I also felt the threat of its loss. The real possibility that one of my children could die, that I could fail to protect them, was shattering. Buddhism holds that the kind of Presence Matthiessen referred to, while real, is transient. It cannot be held onto. And I know that the way I eat is both a celebration of transience—the enjoyment of the texture and tastes of the moment—and a fight against it. I am nibbling at a saucer full of chocolate for three hours; I am making goodness and pleasure last. I am refusing to accept that pleasure and calm and Presence are not enduring states. I will prove otherwise, with my food magic. After a hamstring injury that kept me away from yoga for a couple of months, I mentioned to my teacher, my first day back, that the thing I’d missed most was not the postures, the supposed work of the yoga, but the deep breathing the poses make necessary. She told me she’d once read that ex-smokers miss the nicotine less than the inhale. If we were all better adjusted, we might be able to dispense with the props of cigarettes or chocolate or whatever else to access our particular meditative state, but for some of us the best we can do is to find it within our particular constellation of dependency and neurosis.

There’s a psychotherapist I see every couple of months when I need to travel from my suburb to a nearby city. Not long ago, talking about some professional milestones, I stumbled upon the true and startling feeling (rather than the intellectual understanding) that nothing I achieved was ever going to be enough. It did not matter what good things happened in the future, I would always eventually want more. I saw that the same was true of food and always had been. I could be satisfied with this meal, this snack, but the nagging feeling of need would not only return but increase. In the days after this conversation, while my food cravings weren’t reduced, my ability to ignore them had improved. If a chunk of chocolate was only going to lead to a desire for two chunks tomorrow, why bother? A productive insight, surely. Although my diet is quite healthy in most respects, it wouldn’t hurt me to replace some of the sweets I eat with larger portions of vegetables and fish and, I don’t know, quinoa. It wouldn’t hurt to eat less between meals. Is it possible, I wondered, that not being so satisfied by my eating—not finding quite so much pleasure in it—might be the final stage of my, as they say, journey into health?

If so, I am perversely ambivalent about that. If I lose whatever is left of my eating disorder, I will lose quite a lot of enjoyment; I will lose the smoker’s deep inhale. Unless losing the behavior means that the anxiety that drives it will have disappeared, too—in which case I might find myself quite a different person, one beyond my capacity and perhaps desire to imagine.