In practical ways, I was first introduced to Ensure nutrition shakes in late spring 2002. For eighteen months, a span that included the attacks of 9/11 and the beginning of the decade-plus of war that followed, my stepfather had been undergoing treatment for cancer. We were very close. Paul had married my mother a few years after my father died, and over their time together he behaved in ways that assured her she was not alone in raising these three kids.

In practical ways, I was first introduced to Ensure nutrition shakes in late spring 2002. For eighteen months, a span that included the attacks of 9/11 and the beginning of the decade-plus of war that followed, my stepfather had been undergoing treatment for cancer. We were very close. Paul had married my mother a few years after my father died, and over their time together he behaved in ways that assured her she was not alone in raising these three kids.

Cases of Ensure were sold from a bottom shelf of the Sentry grocery store in the town where I grew up, Waterford, Wisconsin, and I bought at least one case, maybe more, in the final weeks of his life. Even then, time was a blur. Some sleepless nights, some long naps during the day. Visits from a priest and a string of hospice nurses. As much Brewers baseball as we could consume on the television. He was confined to a hospital bed set up in the family room. Home from New York, I stayed in the guest bedroom at the other end of the house. With the door open through the night, I could see him from my bed while he slept or quietly prayed. Mostly he slept.

Paul ate very little in those weeks. He had neither the appetite nor the energy. To feed him anything at all—to continue to keep him alive was how I saw it—my family resorted to food products that made hydration and nutrition easy, fruit-flavored ice pops and vanilla Ensure. He died anyway.

This is something I haven’t thought about in years: how we fed him. But then, recently, I began thinking about feeding Paul and buying Ensure in bulk, about the lengths we’ll go to in order to keep someone alive, about the boundary between death and life. About what one life can teach us.

This past winter, two books were published that ought to reshape how we understand the US-led wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Last December, Melville House released The Senate Intelligence Committee Report on Torture, a document that had been made available by the Senate committee earlier in the month in an electronic format that was slightly cumbersome. Putting it between covers, said the press’s copublisher, Dennis Johnson, was part of its “duty to try and get this report out there to the widest possible audience.”

Then, in January, Little, Brown released Guantánamo Diary, a firsthand account of the detainment of Mohamedou Ould Slahi, a Mauritanian who has never faced formal charges and, despite a 2010 order by a US District Court judge for his release, remains in lock-up to this day. His detainment began when he turned himself over to Mauritanian police in late 2001. The manuscript was written in the summer and fall of 2005, after Slahi had been given certain allowances—a TV/VCR, some books, a chance to garden and the occasional company of another detainee. Paper and something to write with. In the book’s introduction, editor Larry Siems explains: “Under the strict protocols of Guantánamo’s sweeping censorship regime, every page he wrote was considered classified from the moment of its creation, and each new section was surrendered to the United States government for review.” Even so, Slahi hoped the book would reach an American audience. “What do the American people think?” he writes near the end of the diary. “I am eager to know.” And after more than six years of legal wrangling by a team of pro bono attorneys, the pages have been declassified.

Presenting the book, Siems insists that Slahi’s story—“one man’s odyssey through an increasingly borderless and anxious world”—is “an epic for our times.” To me the literary analogue is more grounded—and more damning—than the epic. Slahi, who is shipped overseas (from Mauritania to Jordan to Bagram Air Base to GTMO) and held in chains, who learns English from his guards and interrogators, who insists on the veracity of his story, has composed what seems like a modern-day slave narrative.

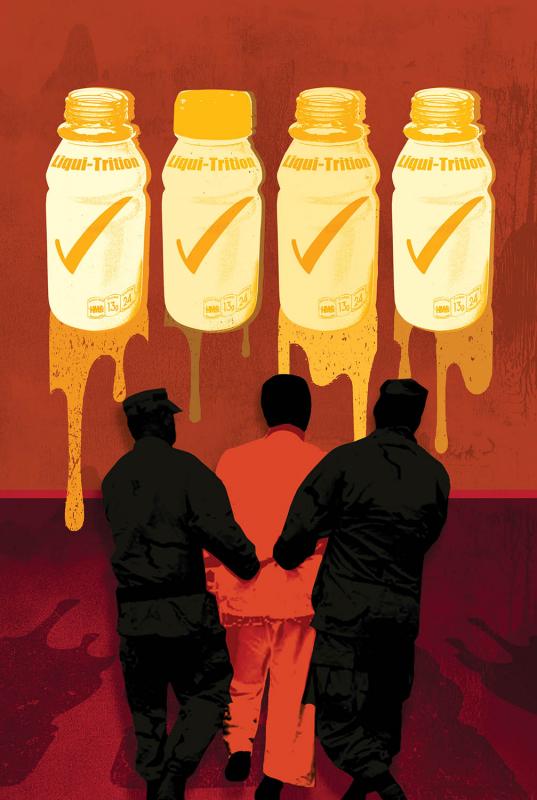

Most of what I’ve seen written or discussed on television about food and the Senate’s torture report has highlighted what’s called “rectal rehydration” or “rectal feeding.” This is both what it says it is and not at all what it says it is.

For instance, the report includes an account of detainee Majid Khan’s having a lunch of hummus, pasta with sauce, nuts, and raisins—all of it pureed and then “rectally infused.” Both Khalid Shaykh Mohammad and Abu Zubaydah, seen to be high-value al Qaeda operatives, underwent similar “fluid resuscitation.” In M0hammad’s case, the procedure was carried out because a CIA Office of Medical Services specialist claimed it could help “clear a person’s head.” It was a way to assert “total control over the detainee.” Basically, Mohammad was sodomized. They all were.1

Ensure, the nutrition shake, is mentioned nearly a dozen times in the Senate report. The drink was administered rectally to Khan (two bottles) and Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri. In al-Nashiri’s case, the report states (quoting a document whose title is redacted), Ensure was infused into him “in a forward-facing position (Trendlenberg) [sic] with head lower than torso.”2

But detainees also drank Ensure. Lots of it. They almost certainly drank it more than they ever had it “infused.” Bringing detainees into what’s described in a 2005 torture memo as a “dependent state” involved “dietary manipulation,” which, says the memo, “involves the substitution of commercial liquid meal replacements for normal food, presenting detainees with a bland, unappetizing, but nutritionally complete diet.” With this liquid diet and its “complete, balanced nutrition,” the memo continues, the main concern seems to have been the number of calories detainees were provided. Limits were stipulated:

Calorie requirement: The CIA generally follows as a guideline a calorie requirement of 900 kcal/day + 10 kcal/kg/day. This quantity is multiplied by 1.2 for a sedentary activity level or 1.4 for a moderate activity level. Regardless of this formula, the recommended minimum calorie intake is 1500 kcal/day, and in no event is the detainee allowed to receive less than 1000 kcal/day. Calories are provided using commercial liquid diets (such as Ensure Plus), which also supply other essential nutrients and make for nutritionally complete meals.

A darkly comic footnote to this moment in the memo, a footnote that is also intensely tone-deaf, attempts to offer some context for this calorie restriction:

While detainees subject to dietary manipulation are obviously situated differently from individuals who voluntarily engage in commercial weight-loss programs, we note that widely available commercial weight-loss programs in the United States employ diets of 1000 kcal/day for sustained periods of weeks or longer without requiring medical supervision. While we do not equate commercial weight-loss programs and this interrogation technique, the fact that these calorie levels are used in the weight-loss programs, in our view, is instructive in evaluating the medical safety of the interrogation technique.

Context here seems to be everything.

Yet when considering those who drank liquid meal replacements—and they basically all did—calorie counts and blandness don’t account for what is most significant, and most horrifying, about the Senate report’s revelations concerning dietary manipulation. It may be that feeding someone nothing but negligible servings of terrible liquid food doesn’t amount to torture, but what is missing from this description is that without Ensure or some other nutrition shake, detainees could not be subjected to the waterboard.

Figuring this out—the essential place for food in what’s inarguably torture—seems to have been a matter of nearly disastrous trial and error for interrogators and their medical-support personnel. In 2006, Abu Zubaydah reported to the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) that for a period of two to three weeks beginning August 4, 2002 (the Senate report notes), five months after being shot and captured in Pakistan, he was fed nothing but water and Ensure. By mouth.

Here’s why. “So it begins,” wrote a medical officer overseeing Zubaydah’s torture.

The sessions accelerated rapidly progressing quickly to the water board after large box, walling, and small box periods. [Abu Zubaydah] seems very resistant to the water board. Longest time with the cloth over his face so far has been 17 seconds. This is sure to increase shortly. NO useful information so far…He did vomit a couple of times during the water board with some beans and rice. It’s been 10 hours since he ate so this is surprising and disturbing. We plan to only feed Ensure for a while now. I’m head[ing] back for another water board session.

Beyond creating a condition of absolute dependence, and beyond providing a “nutritionally complete diet,” these bottles of “bland, unappetizing” Ensure were essential to keeping victims of torture from aspirating their own vomit and dying on the board. Zubaydah had given the medical officer quite a scare.

And so, Ensure became part of Zubaydah’s “aggressive phase of interrogation,” which the Senate report tells us went on in “varying combinations, 24 hours a day” for twenty days, and involved a great deal of time on the waterboard—two to four sessions per day, “with multiple iterations of the watering cycle during each application.” Pause for a moment on the phrase watering cycle. These sessions totaled at least eighty-three.

In his April 12, 2007, testimony before the Senate committee, then CIA Director Michael Hayden offered what he saw as “key contextual facts” concerning Zubaydah’s diet.

Abu Zubaydah’s statement that he was given only Ensure and water for two to three weeks fails to mention the fact that he was on a liquid diet … because he was recovering from abdominal surgery at the time.

Once again, “This testimony is inaccurate,” says the Senate report. In fact, the report continues, Zubaydah had been fed solid food shortly after he was released from the hospital in April 2002, and his experience on the waterboard served as a kind of model for at least thirty other detainees. The May 10, 2005, Justice Department memo, signed by Steven G. Bradbury, Principal Deputy Assistant Attorney General, is conclusive: “The waterboard may be used simultaneously with two other techniques: it may be used during a course of sleep deprivation, and as explained above, a detainee subjected to the waterboard must be under dietary manipulation, because a fluid diet reduces the risks of the technique” (emphasis mine). Ensure. Torture.

When I contacted Abbott Nutrition, the producer of Ensure, about the place of the drink at CIA black sites, the brand-communications manager, Crystal Poole Bradley, wrote with this reply: “I won’t be able to provide any information—we are not commenting on the topic as this is certainly not the intended use of our product. Our products are used worldwide to help people maintain good health and assist in recovery from illness or injury. We did not design Ensure with this use in mind.”

Even between covers, the Senate report remains somewhat cumbersome, but that’s mainly a matter of genre—the black redaction boxes, for one, make for a difficult read. There is an argument to the document, articulated by committee chairman Dianne Feinstein (D-CA) in the book’s foreword. She is clear—and we should be, too—about the context for the torture carried out in the wake of 9/11: “It is worth remembering the pervasive fear in late 2001 and how immediate the threat felt… . We expected further attacks against the nation.” I certainly did. Most of what I remember of the weeks following 9/11 is my own panic. And yet, Feinstein continues, “The major lesson of this report is that regardless of the pressures and the need to act, the Intelligence Community’s actions must always reflect who we are as a nation, and adhere to our laws and standards. It is precisely at these times of national crisis that our government must be guided by the lessons of our history and subject decisions to internal and external review.”

Still, this argument and its conclusion—that the CIA’s “indefinite secret detention and the use of brutal interrogation techniques [were] in violation of U.S. law, treaty obligations, and our values”—come mainly by way of the accumulation of thousands of facts concerning the detention of 119 people between 2002 and 2008. Once again, that we can arrive at this conclusion with Feinstein does not diminish the lives lost to terrorism or overlook the brutality of those responsible for the murders carried out in its name. The Senate report forgives no one for “the largest attack against the American homeland in our history.” It simply lays bare how the CIA decided to respond to that attack with the aim of preventing another one.

The document is encyclopedic. Even so, there are suggestions of human behavior in some of what’s accounted for. Majid Khan, for instance, twice attempts to slit his wrists, tries to chew into his arm and cut a vein at the top of his foot, and uses a filed toothbrush in an effort to cut into his skin at the elbow joint. But by and large, it’s up to the reader of this report to imagine the lives of these men as they’re subject to treatment designed to dehumanize them, to break them, and make them talk. That is a tall order for any reader of bureaucracy.

Guantánamo Diary, on the other hand, is a narrative account of a person, Mohamedou Ould Slahi, interacting with a host of others (“William the Torturer,” “the white driver,” “Mr. Tough Guy,” one interrogator known for never missing his lunch), enduring the unendurable, and eventually discovering a “new home and family.”3 Even the government redactions in the diary appear with an imperfect and imperious human touch: inconsistently blotting out the gender pronouns of female guards and interrogators in what seems a misplaced show of chivalry; at one point striking from the record (it seems) Slahi’s own tears (“I couldn’t help breaking in ———–. Lately I’d become so vulnerable”); eliminating all record of a poem—everyone’s a critic!—which now extends like an optical illusion over nearly two full pages of redaction and is signed simply: “—by Salahi, GTMO.”

In other words, there is life in Guantánamo Diary that does not—perhaps cannot—appear in the Senate report. And there is one life in particular, Slahi’s, a life under continual threat—not quite a threat of death, but close—that accuses us, and makes the reading difficult for a different reason, by revealing what a human life under torture really is. At one level, it’s a life like any life. Like mine. Or yours. My father’s or stepfather’s. My son’s. A life you’d do most anything to preserve. At another level, it’s a life so different from my own, so seemingly singular, that the idea there are others like Slahi is a terror of its very own.

Slahi’s accusation, if a life can be such a thing, makes me think of a line from South African novelist J. M. Coetzee’s Elizabeth Costello. Speaking of the millions put to death by the Third Reich between 1942 and 1945, the eponymous Costello notes in a lecture: “These are numbers that numb the mind. We have only one death of our own; we can comprehend the deaths of others only one at a time. In the abstract we may be able to count to a million, but we cannot count to a million deaths.”

While the numbers themselves are surely less numbing, it is only in the abstract that we are able to count the Senate report’s 119 black-site detainees (nearly forty of whom were tortured). Only in the abstract are we able to count the 780 people sent to GTMO since 2002, and the 122 who remain there, including Slahi. If we want to comprehend the lives of others, we must do so one life at a time. And of those who’ve endured the horrors of CIA black sites and GTMO, Slahi’s life is the first one we can really know.

Torture victims like Slahi all understand at one level that their lives—that they stay alive—are of central importance to those who torture them. To murder Slahi would be a war crime. To end the life would be to end whatever trickle of information has come already and any hope—and this hope seems to be everything—that information may still come with time.4

Here is Slahi, detained in GTMO’s Camp Delta, in the summer of 2003:

“How does your new situation look?” —————- asked me.

“I’m just doing great!” I answered. I was really suffering, but I didn’t want to give them the satisfaction of having reached their evil goal.

“I think he’s too comfortable,” —————- said.

“Get off the chair!” —————- said, pulling the chair from beneath me. “I’d rather have a dirty farmer sitting on the chair than a smart ass like you,” ————– continued, when my whole body dropped on the dirty floor. ———————————————— killing me. Since June 20th I never got relief from them.

And here is what Slahi sounds like to me: I know they can’t kill me, but they seem to be killing me. I know I can’t die here, but I seem to be dying.

It may come as no surprise that in these matters of life and death and the precarious, seemingly porous boundary between the two, Slahi regularly reflects on food. In a world of secrecy, other people are known to him by what and how much they eat.5 The government efforts to assert total control have worked: His detainment is described in terms of what sustenance was made available to him, his ruined appetite, when he could eat and at what pace.

The record that results, this diary, reveals a kind of obsession with eating and being eaten. (Is it any wonder that at one point Slahi says to a GTMO interrogator, “I don’t like speaking about food”?) Life and the dread of being systematically destroyed exist side by side: “I proceeded to the gate like a sheep being led to her butcher.”

Slahi’s interrogations are announced with the scrape of heavy chains and a bellow of “Reservation!” At one point, when presented with crimes he’s meant to confess to—a leadership role in al Qaeda, his efforts recruiting for the cause—Slahi turns to the kitchen for a metaphor: “As you can see,” he writes, “my recipe was already cooked for me.” Faced with a new interrogator early in his GTMO detainment—“just arrived from Washington,” the man says, carrying McDonald’s with him—Slahi comes to understand that there are various government agencies all “try[ing] their chances with detainees.” So he makes the apt comparison from his former life: “It’s very much like a dead camel in the desert, when all kinds of bugs start to eat it.” Indeed, the central metaphor of Slahi’s entire detention—also about the relationship between food and violence—comes from a Mauritanian folktale about a man who is fearful of roosters.

“Why are you so afraid of the rooster?” the psychiatrist asks him.

“The rooster thinks I’m corn.”

“You’re not corn. You are a very big man. Nobody can mistake you for a tiny ear of corn,” the psychiatrist said.

“I know that, Doctor. But the rooster doesn’t. Your job is to go to him and convince him that I am not corn.”

The man was never healed, since talking with a rooster is impossible. End of story.

“For years,” Slahi concludes, “I’ve been trying to convince the U.S. government that I am not corn.”

The government is still apparently not convinced.

By my count, Slahi twice refers to Ensure over the course of his detention, both times in GTMO. (Reminder: His detention there has gone on another nine years since he last wrote.) The first was when he arrived in Cuba in August 2002, when “the prints of Jordan and Bagram were more than obvious.” Slahi was barely held together (“I looked like a ghost”). And good to its word—“Our products are used worldwide to help people maintain good health and assist in recovery from illness or injury”—Ensure helped him recover. The second reference suggests that the meal replacer had remained part of his medical treatment during his first year at GTMO, and yet, throughout July 2003, as the torture grew “day by day,” he recalls, interrogators began to plan their “reservations” to overlap with the distribution of his medications, including his Ensure.

These reservations included sexual abuse. On one occasion, Slahi reports, two female interrogators removed their blouses and started talking dirty. This, he says, he minded less than what followed:

What hurt me most was them forcing me to take part in a sexual threesome in the most degrading manner. What many ———— don’t realize is that men get hurt the same as women if they’re forced to have sex, maybe more due to the traditional position of the man. Both ———— stuck on me, literally one on the front and the other older ———— stuck on my back rubbing ———— whole body on mine. At the same time they were talking dirty to me, and playing with my sexual parts.

Slahi’s response was to pray. During Ramadan 2003 interrogators forbade him from fasting; he was fed by force. He tried a hunger strike, but it didn’t seem to impress anyone.

Of course they didn’t want me to die, but they understand there are many steps before one dies. “You’re not gonna die, we’re gonna feed you up your ass,” said —————-.

Slahi does not say one way or another whether he was fed this way.

There are many steps before one dies. This is what I remember now about Paul, my stepfather, at the end of his life. First he couldn’t quite rouse himself from bed one morning. He feigned interest in a weekend television program about bass fishing. My mother and I eventually got him to the car and the cancer center, where they told us there wasn’t much time. Then he came home and watched baseball, dozed through time with his family, and received Communion wafers from the visiting priest. Even the smallest bits, the crumbs, were enough; every morsel was the miracle. He was fed. The final days were quiet.

I can’t tell how appropriate it is that a few weeks spent reading about torture calls to mind the way my stepfather died and how we fed him in the end. But the effect of the memory is sympathy. And thinking back to a death you know strikes me as a natural response to reading the details of torture, if only because torture exposes the likeness, the porousness, between death and life.

“For instants at a time,” Coetzee writes, filling out a speech by his protagonist Elizabeth Costello, “I know what it is like to be a corpse.”

The knowledge repels me. It fills me with terror; I shy away from it, refuse to entertain it. All of us have such moments, particularly as we grow older. The knowledge we have is not abstract—‘All human beings are mortal, I am a human being, therefore I am mortal’—but embodied. For a moment we are that knowledge… . For an instant, before my whole structure of knowledge collapses in panic, I am alive inside that contradiction, dead and alive at the same time.

Torture ought to fill us with terror. It makes corpses of the living. For years we refused to entertain that the US would do such things. There are some who still refuse to entertain that it happened in our name, so they continue to call it something else.

But now, with these books, we know what happened. We know the scope of US torture and we know the effects of torture on one man’s body. The knowledge we have is not abstract. And while its illegality is clear and its practice obviously flouts what we consider American values, what these books now suggest is that the only argument we need against torture is sympathy—the faculty, as Coetzee puts it, “that allows us to share the being of another.”

1. According to then CIA Director Michael Hayden, testifying before the Senate committee on April 12, 2007, “Threats of acts of sodomy, the arrest and rape of family members, the intentional infection of HIV or any other diseases have never been and would never be authorized. There are no instances in which such threats or abuses took place.” Noting the “rectal rehydration” and “rectal feeding” found in the CIA interrogation records, the Senate committee insists that Hayden’s testimony is inaccurate and provides the evidence under the heading “threats related to sodomy, arrest of family” in Appendix 3 of the report.↩

2. “Trendelenburg” refers to a position people are placed in for some medical procedures (and also for waterboarding); named for the German surgeon Friedrich Trendelenburg, this position typically involves a tilted table or bed, where a patient lies supine so that her pelvis is higher than her head. Al-Nashiri seems to have been flipped over for this infusion of Ensure, and “forward-facing” seems like a euphemism for “face down.”↩

3. Slahi describes this “new home and family” as part of phase three of his detainment. Phase one, the worst, he says, was the mad struggle—“I almost lost my mind fighting”—to escape his confinement and return to his family. “Phase two,” he says, “is when you realize for real that you’re in jail and you possess nothing but all the time in the world to think about your life—although in GTMO detainees also have to worry about daily interrogations.” Phase four Slahi scratched into the margins of his original manuscript: “getting used to the prison, and being afraid of the outside world.”↩

4. By Slahi’s telling, he never knew and never delivered anything of value. He gave interrogators what they wanted. In December 2005 testimony before an Administrative Review Board at Guantánamo, Slahi said: “Because they said to me either I am going to talk or they will continue to do this, I said I am going to tell them everything they wanted… . I brought a lot of people, innocent people with me because I got to make a story that makes sense. They thought my story was wrong so they put me on [a] polygraph.” In the diary, Slahi’s polygraph test appears as nearly seven pages of solid redaction. In a footnote after this long redaction, editor Larry Siems notes that, according to Jess Bravin’s book The Terror Courts, Slahi’s testimony included five answers of “No” to questions about his involvement in terror plots or organizations. According to the Military Commission’s prosecutor handling Slahi’s case, these answers were “considered potentially exculpatory information.”↩

5. Early on in the diary, Slahi writes of his captors at Bagram Air Base, a “bunch of dead regular U.S. citizens”: “What’s wrong with these guys, do they have to eat so much? Most of the guards were tall, and overweight.” He later turns this moment into a broader, somewhat stupefied indictment of the American way of eating: “And Americans worship their bodies. They eat well. When I was delivered to Bagram Air Base, I was like, What the heck is going on, these soldiers never stop chewing on something. And yet, though God blessed Americans with a huge amount of healthy food, they are the biggest food wasters I ever knew: if every country lived as Americans do, our planet could not absorb the amount of waste we produce.”↩