I was born in Queens in 1975—the year of the infamous New York Post cover “Ford to City: Drop Dead,” when New York City was about to declare municipal bankruptcy, and the federal government was desperately trying to divorce urban America. The New York of my childhood was one of boarded up buildings, intentional arson by landlords, graffitied subway cars, general dissolution of city services, decay and the chaos that comes with it. I grew up around the detritus of urban refuse, and the images I find beautiful and compelling are still things that are cracked or post-industrial—glassphalt sidewalks glittering at night, the shout of scratchiti on a subway car window, and the gentle curve of jumper prevention fences on highway overpasses. Detroit is not New York, and though the visual language of urban decline is familiar to me and spans geography, Detroit is a different story.

In 1950, Detroit was the fifth largest city in America, with 1.8 million people. Current statistics put the population around 800,000, which still makes Detroit the eleventh most populated city in the US. It is also 80% black, according to the last available US census. Issues surrounding race, racism, and racialized poverty are unavoidable in any discussion of Detroit. As of 2009, 36 percent of the people in Detroit live below poverty level, as do 50 percent of the children in the city under the age of eighteen. The city is 139 square miles, which includes approximately 40 square miles of unoccupied land (an amount equivalent to the area of San Francisco), and roughly 90,000 abandoned or vacant homes and residential lots, according to the non-profit Data Driven Detroit. Thirty percent of the city’s housing stock is currently vacant. Mayor Dave Bing pledged to knock down 10,000 (of about 33,000) structures in his first term as part of a plan to condense Detroit to reflect its shrinking population, and is currently making good on his promise.

These abandoned spaces become active sites of meaning-making and narrative and reuse both for people inside the city and outsiders who report on disintegration and abandonment, the spectacle of large-scale decay and transformation, the violence perpetrated on these structures by humans and nature and time.

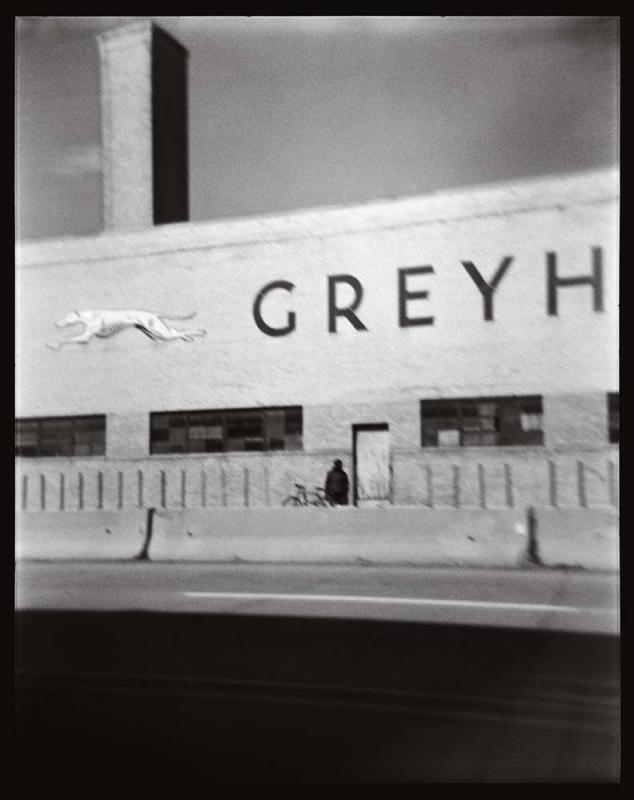

One could argue right now that in addition to cars, Detroit’s biggest export is representations of the city itself. In the last year, three major photo books on the ruins of Detroit have been published (Detroit Disassembled, Lost Detroit, and The Ruins of Detroit) that depict, as the titles would suggest, Detroit in ruins—but lush, colorful, gorgeous ruins dubbed “ruin porn” by many inside Detroit who feel that outsiders are exploiting the city, and selling the rest of the country an inaccurate portrait of day-to-day life in the Motor City (though it’s important to note that Lost Detroit was created by two Detroiters—Sean Doerr and Dan Austin). At the end of 2009, Time magazine bought a house in Detroit and installed journalists, photographers, and bloggers in it. “Detroit,” the editors wrote, “has been misunderstood, underreported, stereotyped, avoided and exploited for decades. To get it right, we decided to become stakeholders.” But how do you “get it right” when it comes to presenting an entire city to a national readership? Time saw Detroit as “a great American story,” as “a window into the challenges facing all of modern America.”

But is it appropriate to view Detroit as a cipher or harbinger—the quintessential American story of boom and bust?

I went to Detroit in the summer of 2010, with the intention of reporting on the city in verse, alongside radio journalist Jesse Dukes and Kate Ringo, a VQR intern who joined us for the trip. We allowed ourselves to be guided by the city itself—the neighborhoods and buildings, and most importantly, the people in and around them—toward what stories needed to be told. Later, photojournalist Ryan Spencer Reed, who had started work earlier on a separate Detroit project, went back to photograph some of the places we explored and the people we spent time with.

Our journey began with Dr. Jerry Herron, dean of the Irvin D. Reid Honors College at Wayne State University, who writes extensively on Detroit. “Detroit is the single greatest American success story ever contrived by humans in this country,” he told us. “More people came here from all over the place, from the United States, from across the globe to build an industrial machine that created wealth faster, for more people than anything humans have ever put together on the surface of our planet,” he insisted. We had brought a copy of Andrew L. Moore’s book Detroit Disassembled with us, and Jerry pointed to photos of the old Cass Tech High School, with its blown out windows and fully stocked, abandoned chemistry lab. He flipped to photos of the old Michigan Theater, now a parking structure. “These artistic images take America’s great success story and put it within the context of no context, so that you might look at this and say, ‘look—signs of visible wealth. What kind of people could walk away from something like this? Who would do that kind of thing?’ And you can walk away and think there must really be something about those people in Detroit: they’re violent, they’re wasteful. But what you’re looking at is a snapshot of those people in America … By the 1970 census, the majority of Americans had abandoned central cities and had already started this great migration to suburbia, because we could. Nowhere did that happen faster than in Detroit, because we were richer.”

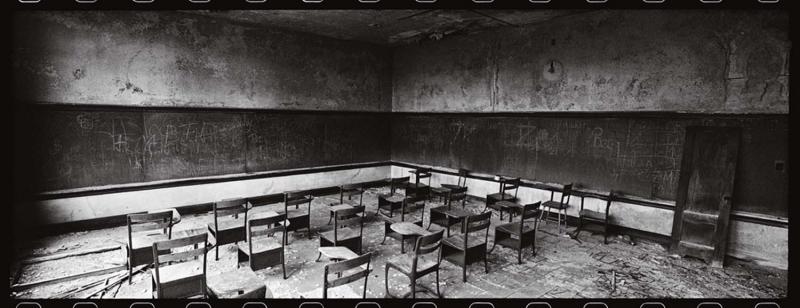

Before we went to see Herron, the questions we started with had to do with the spectacle of Detroit, and, as he writes, the energy released by a city in decay. What narratives occurred in the past in these spaces? What’s happening in them now? What might happen in, to, or around them in the future? In many ways, these changing spaces of Detroit—what people have taken to calling the “ruins” of Detroit—are simultaneously our most sacred and most desecrated communal spaces. People on the margins of society—homeless, scrappers, graffiti artists, urban explorers, journalists, photographers, visual artists, delinquents, junkies—actively use these spaces for their survival or their work. They make pilgrimage to them, take shelter in them, remove things from them, strip them, document them, add to them, and inscribe them. These abandoned spaces become active sites of meaning-making and narrative and reuse both for people inside the city and outsiders who report on disintegration and abandonment, the spectacle of large-scale decay and transformation, the violence perpetrated on these structures by humans and nature and time. We, as viewers, lament over them, are awed by them, can’t look away.

We first met Al Brewer, a former Ford factory worker, after Delores Casey, a former GM factory worker, offered us some of her fresh roasted peanuts in a lot on the corner or Frederick and St. Aubin in east Detroit. During the week, the lot looks like much of the eastern end of the city—a grassy urban meadow, deserted, save for the jigsaw of plywood outlining a makeshift stage on one end of the field. But every Sunday from May through October, the lot becomes the John’s Carpet House Blues Jam, where blues musicians start playing hard under a giant chestnut tree at three o’clock and don’t stop until sunset. The music is free, though Big Pete Barrow passes a hat around to all the people sitting in their bring-your-own lawn chairs, to collect money for lawn-mowing, gas for the generator to power the amps, and the Porta-John rental. Al, a middle-aged African American guy, was sitting next to Delores, on a lawn chair under an umbrella. It was August hot, and the blues jam was packed with folks who were dancing or head-nodding to the music, grilling kielbasa on portable hibachis, selling fresh-roasted peanuts in paper bags with twisted tops, or hawking cold Budweisers from Styrofoam coolers.

In the last few years, Detroit’s official unemployment rate has oscillated from 20 to 30 percent, while current Detroit Mayor Dave Bing puts the actual unemployment rate around 50 percent. Historian Thomas J. Sugrue tells us that in 1950, one-sixth of the jobs in the US were related to the auto industry. In the mid-1930s, at its peak, over one hundred thousand people worked at the Ford Rouge plant. By 1990, the workforce at the Ford Rouge had plummeted to just a little over six thousand, and has been holding steady at that number for the last twenty years. Any portrait of Detroit would be incomplete without auto workers, and their voices, based on extensive interviews we did, worked their way into many of my poems. In addition to Al Brewer, some poems feature snippets from Lolita Hernandez, a UAW worker for over thirty years, who was one of the first women to be hired at the Clark Street Cadillac plant and worked there for over two decades.

But we came to see that just as important as auto plant closures—maybe more important—was the constriction of Detroit’s public schools.

At the intersection of Chene Street and Illinois Street in East Detroit sits what’s left of Frederick Douglass High School, built in 1963 and closed in 2007, after it became Douglass Academy. It’s one of sixty-two schools being offered for sale by the Detroit Public Schools’ Office of Real Estate, for “Highest/Best Offer.” The school had once been boarded up with beige Vacant Property Systems (VPS) security panels, and you can still see some that have been ripped off the front of the building hanging askew. The school is wide open. All of the floor to ceiling windows, which make up a full third of the exterior of the school, have been shattered, and you can look straight through one side of the hallway to the foliage on the other side. The entire outside of the building has been tagged in a riot of colorful bubble letters—Kosher, Pear, Arch, Holy, Purge, Toked, 2010 Cold Hands, Where’s Ya Fuckin Head At? Inside, all the white ceiling tiles have been torn out so that scrappers can scavenge the wires and pipes. Yellow insulation, bent metal supports, stray wires, and PVC piping hang from the ceiling.

Oren Goldenberg, a filmmaker whose most recent documentary Our School chronicles daily life in three public high schools, took us on a tour of both shuttered schools, like Mackenzie, and schools that were open and serving their communities, like the Catherine Ferguson Academy, which has a working farm and is specifically set up to educate pregnant teens and young mothers. Detroit’s school district has been in turmoil since 1999, when the Michigan Legislature stepped in due to mismanagement and constant infighting between the school board and the superintendent. In February 2009, consultant Robert Bobb was appointed as the Emergency Financial Manager of DPS. As of February 2011, DPS has a $327 million budget deficit. The Detroit Public School system currently serves about 74,000 students, and reported a 58 percent graduation rate in 2009, while an Education Week report in 2007 put Detroit’s graduation rate at 24.9 percent; in the last five years, school enrollment has dropped 50 percent. Since 2005, one hundred public schools have closed. “You’re single-handedly changing the fate of the neighborhood when you close a school,” said Oren. “Kids are going to jail and dying. If you close the school, there’s nothing here.”

At beginning of January 2011, Robert Bobb had proposed closing seventy more schools, leaving DPS with seventy-two schools. The Detroit News reported that Bobb recommended simply abandoning the closed buildings without cleaning and securing them, boarding them up or storing their contents; this would save the district $12.4 million. While it’s sad, disjunctive, and outrageous to see schools with supplies still in them abandoned, the human costs of the school system’s failures in Detroit are far more insidious.

We visited teachers at InsideOut, a literary arts project that sends writers into public schools, who told us about the chaos that school closures had injected into an already challenged school system, serving an extremely fragile population. We spoke to Lolita Hernandez’s neighbor, a public middle school teacher named Wendy Ford, who told us about the practice DPS had of laying off teachers with less than twelve years in the system every single year, and then only hiring some of them back. This year, 2010–11, was the first school year where teachers with more than twenty years in the system were also getting layoff notices. The letter that comes in the mail calling a teacher back to school and canceling her layoff notice is called a rescission notice. Every DPS teacher we spoke with was intimately familiar with these notices.

Despite the hardships of working for an under-funded and chaotic school system which serves one of the most fragile and poverty-stricken populations in the country, despite the fact that even the most talented teachers are losing their jobs each April, every last teacher we spoke with was dedicated to their profession. “I can imagine after the battle of Antietam the Red Cross walking around trying to find people who are still alive. That’s kind of how it is,” said Wendy, about teaching in a DPS middle school. “I can’t look at the carnage and see it as carnage. I gotta keep going. Going over and above is just normal. You really can’t sleep at night unless you do something over and above, but what they need always far exceeds what we can do, and that becomes a normal state. I’m needed here.”

Lolita Hernandez also sent us to see Joan Nash, another public school teacher, with over twenty-five years in the DPS system. She had been teaching at Crosman Alternative High School, which was slated to close in the Fall 2010, and had received a layoff notice in April—her second, in all of her years in the system. Her partner, Martin Quiroz, a talented visual artist and art teacher, had just passed away in June, and Joan blamed his death partially on the stress of his constant layoffs. Despite the fact that he was an award-winning teacher and dedicated community activist, Martin had been laid off ten times in ten years of working for DPS, sometimes twice a year. “They called him back to work in November, he worked November through January, and then at the end of January they gave him a layoff date of February or March, then right before the layoff date they cancelled the layoff. So we’re working under a tremendous amount of stress,” Joan said. She also explained to us that even if a teacher gets called back in September, it doesn’t mean that they’ll still have a job come December. Count Day (the October 4, each year) is the day where a school’s attendance determines the amount of state funding each district receives. Once final figures from Count Day are in, there are usually a round of layoffs in November.

When Ryan Spencer Reed, the photojournalist we were working with on this project, went back to photograph Joan, she was no longer in deep mourning for her partner. When we had spoken with her, she had told us that she would love, in an ideal world, to run a middle school reading lab. As of August 30, 2010, all layoff notices for DPS had been rescinded, and Joan, as it turns out, was placed in a high-performing middle school called Clippert Academy in Southwest Detroit, where she now teaches language arts. The news for the school system as a whole, however, has gotten worse. As of February 21, 2011, the Detroit News reported that state education officials have ordered Robert Bobb to immediately implement his proposal to close half of the district’s schools, raising high school class sizes to an average of sixty students.

Photos of any kind stop time. We, as viewers, assume that the picture we see documents an as-is mostly unchangeable reality. Frozen images of the ruins of Detroit lead us to the inevitable idea that in the Motor City, there’s no progress—only entropy, dissolution, and regress—that things will only get worse. When Ryan photographed a sign at the Packard Plant in 2008, most of the letters were still left spelling out MOTOR CITY INDUSTRIAL PARK. When we returned two years later, they were nearly all gone. Vandalism, disintegration, nature, and fire are real in Detroit, but so is incremental progress. Joan Nash’s situation actually improved in the time between our first meeting, and when I spoke with her again six months later. This complicates the reverse narrative of Detroit. Healing is possible—and everything is always shifting; in something as large as an entire city, there is no one story. We spoke with autoworkers, schoolteachers, filmmakers, community activists, professors, urban explorers, photographers, students, amateur historians, architectural history buffs, authors, small business owners, and artists so they could guide us towards some of the stories of Detroit. My hope is that these poems and Ryan’s photos capture some of the threads that make Detroit unique—her history, her people, her challenges, and her triumphs.

Post-Industrialization

This is the single greatest story of American success:

God Bless Our Customers. Fax & Copy Here. Beer

& Wine & Liquor. Gifts & Perfumes & Lottery & Cell.

Check Cashing & Quick Weaves. I saw signs and wonders,

wonders and signs, but no one lugged me from the rubble

with an outstretched hand. I did not rise from the ashes.

In 1914, Henry Ford offered five dollars a day to the men

who assembled the Model T. And the dead were judged

according to their works. What kind of people

could walk away from something like this?

All of us. We like space, we like cars. A city

in decay releases energy: rebar, sirens, razor-

wire, spray paint, a guy pushing a shopping cart

down 2nd Street with a vacuum cleaner in it. Destroy

what destroys you. Then, from the ruins, Hallelujah.

This is happening all over the country. Detroit as cipher

of decay: mirror mirror. And I saw the dead, small and great,

stand before the city. Their fate was tagged on slabs

of plaster with Krylon. And the devil that deceived them

was cast into the lake of fire. And the books were opened.

And the books were burned. What must I do to be saved?

Photograph the bricks peeling slowly off the rear

of the Wurlitzer Building, threatening an alley

where a squatter hangs one pair of shorts

and one shirt on a makeshift clothesline tied

to a busted fire escape running along a wall

which has a single red heart painted in every

cracked window. Those Wurlitzer organs

had such life-like power that they made people

who never sang when they were alone

join in chorus with others. This is where

we start: with great terror,

with miraculous signs and wonders.

All That Blue Fire

Alvin Brewer, former Ford autoworker

I’m from Virginia. Gasburg, Virginia.

And I heard that the plants were hiring,

so what I did, I came up here

for a New Year’s Party.

And after I went to the New Year’s Party,

I didn’t ever go back.

I went to the Ford Motor Company

because they were hiring. That was

the 3rd of January, 1969.

My first job was working in the engine plant,

where they build the motors at.

I just came up here to a New Year’s party

and got this job and never go back.

They have the motors hanging on a line,

and they’d be passing through,

so one guy turns the crank,

one guy put a piston in,

then you turn the crank again,

and another guy put a piston in.

Yeah, they go on down the line

like that. Then when it get out

to another part of the line,

they lay the motor down,

they put the heads on,

spark plugs in.

And then it gone on out—

they turn the motor over,

put the oil pan on,

keep on down the line.

When the motor get to the back,

they be ready to start it up.

They hook up the hoses

and the gas line, start it up

right there, less than half an hour.

When I would go on break, sometimes

I would go back there, watch them guys

hook the hoses up and start em up,

cause I used to like to hear them started up.

All that blue fire be shooting out of there

when the motor first started, cause they

ain’t got no pipes on it.

Sound real loud, that blue fire

from the exhaust system.

Once they put that carburetor on there,

they just pour the gas, hook the gas line up,

hit the accelerator a couple of times,

and there you go. Start right up.

They started it without the body.

The engine don’t be in the body yet.

I just came up here to a New Year’s party

and got this job and never go back.

Man they were having so much fun.

Back then, I didn’t want to go back.

Layoff Notices Have Been Rescinded

Joan Nash, Detroit public school teacher

My partner, he had been laid off ten times in ten years, Joan said.

That’s a lot of stress. In Detroit, it’s very precarious as a teacher.

The Union hotline recording says all April layoff notices have been rescinded.

The hotline says press 1 if you have questions about where to report on Monday.

Joan told us right now she’s going through something personal. Her partner

was in good health, but in the last ten years he was laid off every year, she said.

And the stress—I do feel strongly that the stress—he died the 28th of June.

They call you back in September, and there’s a chance for another layoff in November,

though the Union hotline recording says all April layoff notices have been rescinded.

Joan told us they laid everybody off this year—even her, for the first time

in twenty-five years of teaching, from Crosman Alternative High School, closed this year.

It was stressful for my partner to get laid off, sometimes twice a year, she said.

Joan explained that in the summer or the fall, the rescission notices come.

Do you understand what I’m saying? Everybody does not get called back each year,

but the Union hotline claims, this time, that all teachers have been recalled.

They start you off at a terrible disadvantage, she told us. I’m fifty-seven,

I’ve been teaching for twenty-five years, and the uncertainty makes me want to retire,

but getting back to work would be good for me. It’s just very stressful, she said.

The DFT hotline has confirmed that all April layoff notices have been rescinded.

Borderama

Inside me is a playground, is a factory.

Inside me is a cipher of decay.

I am sometimes a vehicle for absorbing wealth.

I feel daily like I have to defend myself.

Inside me is inbred chaos.

Inside me is America’s greatest manufacturing experience.

Inside me is an assembly line 4 miles long

where the workers who build products

are themselves interchangeable parts.

Inside me is a big blue Cadillac.

Inside me is a shrunken footprint.

Inside me are things that are not relevant

to anyone’s idea of a civilization in ruins—

a moment of consolation, a transitory

slideshow, a centerfold.

Inside me is someone saying we will

rebuild this city. Inside me is the legacy

of tanks rolling down the Boulevard,

an arsenal of scrapped schools

with graffiti on the doors.

Inside me I’ve got

a window

where my heart is

but we hope for better things.

If we don’t act so bad, they won’t close the school.

If you close the school, there’s nothing here.

Inside me is the fate of a neighborhood.

And something hard that refuses to die.

Is that plywood torn off?

Can I fit through that hole?

Inside me they’ve left everything behind:

maps, test tubes, disintegrating plaster,

bent rebar, torn conveyor belts

where three guys worked the engine

and one guy turned the crank.

I was an autoworker for 33 years,

she said, and you learn your job so well

that it looks like you’re part of the line,

it looks like you’re dancing, like the guy alone

on John R Street outside his black sedan—

August night and his car doors open,

music pouring out, doing a graceful

running man. I want to tell him

about the lost colony, the people

that landed and vanished inside me.

And this photographer I talked to

on the phone who thinks Detroit

is still on her way down, hasn’t hit

bottom. But there’s Harmonica Shah

in his overalls in a lot on the corner

of Frederick and St. Aubin singing

if you don’t like the blues, you got a hole

in your soul. If you don’t like the blues,

go home.

Outside the Abandoned Packard Plant

closed fifty-four years, the crickets

are like summer, are like night

in a field, but it is daytime. It is August.

There is no pastoral in sight—only

Albert Kahn’s stripped factory, acres

of busted and trembling brick façade

so vast there must be thousands

of crickets rubbing their wings

beneath makeshift thresholds of PVC

piping tangled in ghetto palm saplings

growing through a deflated mattress top

tossed over rusted industrial metal the shape

of an elephant dropped on its knees

dispensing invisible passengers into

moats of rubble dappled with what?

These crickets, their industrious wings

mimicking silence and song, lonely

background, until one beat-up maroon

Buick flies down Concord, accelerating

like the road just keeps going, like he’ll

actually get away with whatever he’s doing,

then two white cop cars, Doppler sirens

shrieking and braiding, but it is peaceful

other than that—you might think

you’re in the country as in not the city

as in wilderness under the bridge that used to say

MOTOR CITY INDUSTRIAL PARK

and now just punched out eyes and ARK

Inside the Frame

a man leans in the doorway of his not-home

waiting to be photographed from a passing car

by a man who is dreaming of trespassing

and resurrecting the last bricks

from every demolished school [dwelling] church

he ever entered or abandoned himself in/to

before he left Detroit/this city

Rivera painted an infant huddled

in the bulb of a plant, a mother

hoarding apples in her circled arms

a harvest, a plenty

Jewelry * Loans * Cash Fast—

a billboard with a diamond

ring for every finger

and on the walls, so many hands

working the line/turning the cranks

(holy rollers) grasping rocks

while we look on

it don’t exist, says the plywood

door (attended to, cracked open)

at Bill’s Blue Star Disco Lounge,

burned down so the sky shines

through the not-roof on/to Michigan Avenue

the whole road gap-toothed, boarded up

and then Woodward, where the parking

attendant swears he’ll stay outside the frame

in the lot with the cars till the game lets out

Outside the Frame

is a brand new $115 million dollar high school with the same name as the abandoned one outside the frame are two men biking at midnight down John R street with red lights blinking off their cycles like morse code it’s not too dangerous outside the frame are the lines around Michigan Avenue for Slows Bar B Q outside the frame are the larger contexts for these shots the what’s next and what’s next to the slots of abandoned tagged houses and houses that went so long ago that only field is left not even foundations those have grown over with prairie grass did you see the pheasants outside the frame is a functioning farm an urban garden where one horse neighs in the heat nuzzles the dirt outside the frame stands a blue sign with two yellow suns and Hope Takes Root outside the frame is the Obama gas station at the intersection of Plymouth and Wyoming with rebranded awnings & signs & pumps and outside the frame the owner says I have my dream and my dream came true outside the frame is the possibility to do whatever the hell you want no one cares what we do here outside the frame is the blues jam at the corner of Frederick and St. Aubin so bring your lawn chairs to the abandoned lot where they pass the hat for the mowing porta-potties electric generator to run the amps because outside the frame sometimes there’s just nobody around to say you can’t