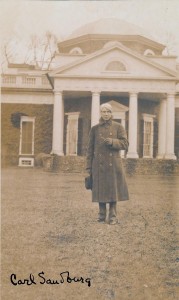

- Carl Sandburg visiting Monticello. (Courtesy of the Clifton Waller Barrett Library of American Literature, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library.)

In 1928, American poet Carl Sandburg was fifty years old and consumed by the most taxing work of his life. Nearly a decade after Chicago Poems (1916) established him as the voice of the Midwest, Sandburg began two more projects that earned him his reputation as one of America’s foremost historians, an expert on the American way of life as seen by “the people.” Enamored with Abraham Lincoln, Sandburg eventually became one of his primary biographers, and it was during this busy period of the 1920s when Sandburg began the first volume of the president’s life, Abraham Lincoln: The Prairie Years (1926). Though that book alone was a cumbersome task, Sandburg also agreed during this time to compile the American Songbag (1928), a collection of nearly 300 scores of American folk music. A musician in his own right—Sandburg was known for his plucky guitar stylings and distinctive baritone voice—as well as an established chronicler of history, Sandburg seemed the natural choice to write this book, though the project would plunge him deep into research.

These encyclopedic works exhausted Sandburg, who, in 1927, relocated his family and home to the tranquil dunes of the Chikaming Township near Harbert, Michigan after a nervous breakdown left him bedridden, doubting the progress of his work. In the midst of this, Sandburg was still writing poetry. During April of 1927 he came to UVa and visited the editor of VQR, James Southall Wilson. Wilson commissioned poetry from Sandburg during this meeting and later wrote to him in June 1927 to follow up, perhaps to remind the preoccupied poet to send his pieces.

“You were good enough when you were here to suggest that you would send some of your poetry to the Virginia Quarterly Review,” writes Wilson. Then, regarding payment, he defers wholly to the famous poet: “We pay usually fifty cents a line (an absurd but usual practice) but should try to meet whatever are your usual rates.” Putting business aside, Wilson also mentions in this letter Sandburg’s “pleasant” visit with writer James Branch Cabell in Richmond during his tour of Virginia, which Wilson heard about from Mrs. Cabell—the central Virginia literati grapevine.

There is no available reply from Sandburg, but his poems were sent within a year after his initial meeting with Wilson, who published the poems in VQR in the July and October issues of 1928. The original manuscripts of the seven poems Sandburg sent all still exist.

After seeing the pages for each issue, Carl Sandburg wrote to VQR twice in 1928, pleased with his publication in the magazine. In these letters, Sandburg’s words crackle with his typical candid style: he fits genuine sentiments into lines so terse that they nearly sound flip, though they are likely just the result of his undoubtedly large pile of correspondence to maintain. Mostly, these letters reveal Sandburg’s affection for Wilson’s work and VQR as a publication.

“[I] sort of feel we’ve traveled a little journey together,” writes Sandburg in a handwritten note to Wilson in August 1928, after seeing the July issue. “I was glad to see my pieces in the Virginia Quarterly Review typography,” he wrote again, in October 1928, “which has a proud strength and a Jeffersonian simplicity. I do hope to look in on your interesting and live corner of the world sometime within a year.”

Wilson published five of the poems during the summer and reserved two for the October issue, because, as he explains in his letter in back to Sandburg in September 1928, they were ones that he “particularly liked.”

These two that Wilson favored are “Moon Path” and “Landscape,” which both pulsate with a particular kind of melancholy. “The little say-so of the moon must be listened to,” writes Sandburg in “Moon Path,” suggesting the yearning of one who believes that nature possesses untold, perhaps unattainable, answers. One can almost imagine Sandburg wandering the dunes during this challenging period after his breakdown, dreaming these poems. All seven would eventually contribute to Good Morning, America (1928), the volume that led the New York Times to accuse Sandburg of having “sat too long at the feet of Walt Whitman” and demand for “fresh combinations and new beauties.”

In 1929, Sandburg changed paths and become solely invested in his catalog of Lincoln’s life. He worked toward the publication of the second volume, Abraham Lincoln: The War Years (1939). His study of Lincoln’s wartime ideology led to Sandburg’s outspoken support of the Allies in World War II and the US’s decision to enter the war. His poetry during this era, represented in The People, Yes (1936), also took on a more overt activist leaning. He began a novel, Remembrance Rock (1948), which tops the list, along with War and Peace, of the longest books of fiction ever written. Taxed once again with epic works, Sandburg retired to Flat Rock, North Carolina, where he and his wife Paula expanded their goat farm.

During this busy decade, VQR managing editor Charlotte Kohler wrote to Sandburg many times to request more poetry, though it seemed that Sandburg’s interests lay elsewhere. After receiving an appeal from Kohler to draft an essay on Jefferson, Sandburg, then renowned as a Lincoln expert, finally wrote in 1943 that “other commitments would not permit of my undertaking of a Jefferson study now.” But he thanked Kohler “for so kindly and thoughtful a letter.”

“Just now I am a little hard-driven,” he would later write in 1945, “but possibly next year in my portfolio you may find something worth printing.” This would be his last communication with VQR. Sandburg, in the sunset of his career, was receiving some 200–400 letters a week, and was understandably weary. Still, his short letters carried the same jovial, personal tone as when he once wrote to Wilson. This candid intimacy, present in even the most mundane of business letters, is the same quality that made Sandburg popular as a poet and as a historian. For the sincerity and understanding he brought to his subjects—the people in America’s present and past—Sandburg stands as a writer whose greatest gift may have been his ability to relate to others.

Manuscripts

Works used: Niven, Penelope. Carl Sandburg: A biography. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1991.

Manuscripts are from Papers of the Virginia Quarterly Review, 1925-1935, Special Collections Department, University of Virginia Library.