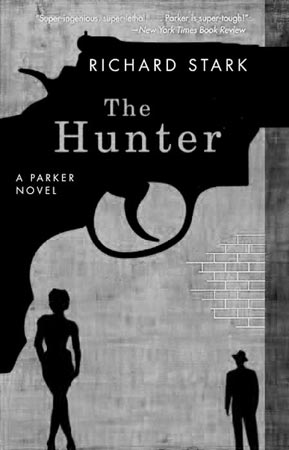

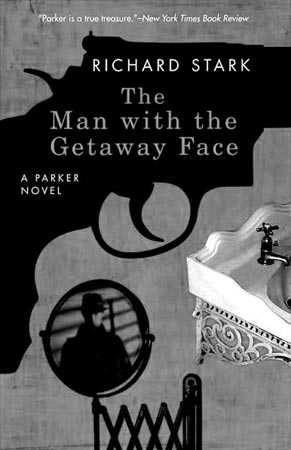

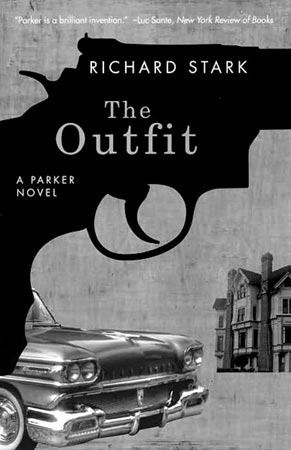

The Hunter, The Man With the Getaway Face, and The Outfit, by Richard Stark (Donald E. Westlake). Chicago, September 2008. $14 paper each

When Donald E. Westlake died on New Year’s Eve, he took a crowd of good men down with him. There were at least fourteen. Maybe more. James Blue. Ben Christopher. Sheldon Lord. Writers, all of them. Some better known than others. Edwin West. Curt Clark. Tucker Coe. Samuel Holt. They wrote science fiction novels and biographies. They wrote soft porn paperbacks and short stories. But none of them will ever write again. Down they went on New Year’s Day. Westlake had even blurbed one of them. “I wish I had written this book!” he crowed of J. Morgan Cunningham’s novel Comfort Station.

But here’s the kicker. He had written the book. He’d written all their books. These men—these writers—they were all Donald E. Westlake. They were his pseudonyms. Some, like P. N. Castor, were one-shot wonders. Others, like Alan Marshall, whose soft-porn titles include All My Lovers, Man Hungry, and Virgin’s Summer, published nearly as many novels as Norman Mailer. All told, Donald E. Westlake published over a hundred books under various names, including his own, but one pseudonym in particular stood above all the others: Richard Stark.

Donald E. Westlake first introduced Richard Stark to the world in 1959 via a short story in the magazine Mystery Digest. Stark’s first novel, The Hunter, appeared two years later, and until 1974’s Butcher’s Moon, the novels kept coming, one, two, three a year. And then they stopped. Stark was put into retirement. It wasn’t until twenty-three years later that Comeback, a new Stark novel, appeared, reviving a series that must surely constitute one of the longest-running in American crime novels.

Last fall, the University of Chicago Press reissued the first three Richard Stark novels in handsome trade paperback editions: The Hunter (by far the most popular of these novels, having first been made into the movie Point Blank starring Lee Marvin and then remade into Payback starring Mel Gibson), The Man with the Getaway Face, and The Outfit. This spring, Chicago released the next three books in the series: The Mourner, The Jugger, and The Score. More are on their way.

The success of the Richard Stark novels can be summed up in a single word: Parker. No first name. Just Parker.

Parker is the series’ hero—or, better yet, its antihero: an unrepentant thief who, for reasons of self-preservation or revenge, must occasionally go on killing sprees. Mostly, he kills those who, in his opinion, deserve to be killed, but every now and again innocent people die, like the asthmatic woman he’d gagged so that he could look out her office window and spy on the building across the street. For the innocent dead, Parker typically mourns for about a paragraph—usually more for his own stupidity than for his victim—before he pushes on, killing a few more people.

Parker is often an enigma, but to understand what lights the plot’s fuse in the first novel, The Hunter—a fuse that continues to sizzle throughout at least the next two novels in the series—we’re provided a bit of backstory: in the aftermath of a heist, Parker is shot by his wife, Lynn, who has been forced into double-crossing him by his partner, Mal Resnick, who needed Parker’s share of the money to buy his way back into the mafia—or “the Outfit,” as it’s called. As a final gesture, Resnick sets fire to the building Parker is in.

Parker—not unlike the Frankenstein monster, who is torched at the end of the classic 1931 movie—is thought to be dead; and not unlike the monster, who emerges from the ruins for many more sequels, Parker survives. Thus, The Hunter opens as Parker is crossing into Manhattan on foot, a monster himself now, as motorists pass him by:

When a fresh-faced guy in a Chevy offered him a lift, Parker told him to go to hell. The guy said, “Screw you, buddy,” yanked his Chevy back into the stream of traffic, and roared on down to the tollbooths. Parker spat in the right-hand lane, lit his last cigarette, and walked across the George Washington Bridge.

The Hunter is primarily the story of Parker settling the score while trying to recoup his stolen money, which ultimately leads him to confrontations with the higher-ups within the Outfit. The Man with the Getaway Face, the second novel in the series, focuses almost exclusively on the mechanics of a heist after Parker gets plastic surgery in order to avoid the Outfit, while the third novel, appropriately titled The Outfit, opens with a hit man from the Outfit trying to kill Parker, prompting him to go head-to-head with the very organization he had been going out of his way to avoid.

All of this may seem like pretty par-for-the-course crime fiction, and by today’s standards, it is. But if you go back to 1962, when this series first began, you would have been hard-pressed to find many crime novels in which the reader is asked to champion the crook. Bear in mind the movie Bonnie and Clyde, which caused an uproar for asking moviegoers to empathize with the killers, wasn’t released until 1967. You could cite Jim Thompson’s novels, which preceded Stark’s by over a decade, but while we’re entertained by Thompson’s pathological narrators, we hardly root for them.

With the Parker series, Richard Stark was breaking new ground by presenting a series character as an unrepentant and amoral antihero. Though these first three books were published in 1962 and 1963, Parker is clearly a product of the fifties rather than the sixties, and if forced to pigeonhole this series, I would say it has less in common with the crime novels of Ross MacDonald and Raymond Chandler than it does Sloan Wilson’s The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit, the story of a man who, after serving in World War II, finds himself deadened by suburban life. He yearns for how alive and, ironically, safe he had felt during the war. The book’s original jacket-flap goes so far as to spell out for the reader what the novel is metaphorically about:

These men are all over America wearing gray flannel. A few short years back, they were wearing uniforms of olive drab. The central theme of this novel is the struggle of a man to adapt himself from the relative security of O.D. [olive drab] to the insecurity of gray flannel. Today many men wear the gray flannel suit and wonder whether this uniform provides as secure a life as the one they had when they were wearing O.D.

The fifth bestselling book of 1955, The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit clearly tapped into something brewing in the collective American psyche and, in turn, inspired similarly themed novels, the most notable (and by far the best of the lot) Revolutionary Road by Richard Yates, published in 1961, a year before the Parker series began. In Revolutionary Road, we find Frank and April Wheeler in the suburbs with two kids, living, by all accounts, a secure life, and yet they are both feeling that they have sold themselves short, and it’s this restlessness and a sense that they’re better, smarter than their neighbors that ultimately leads them to their doom.

More recently, the TV series Mad Men explores this same terrain but with the advantage of a forty-five year remove, and it’s here, in the character of Don Draper, Creative Director for Sterling Cooper advertising agency (played to perfection by Jon Hamm), that I find Parker’s fraternal twin. (If I were casting a new Parker film, I would take a close look at Jon Hamm for the role.) Don Draper is a much darker Frank Wheeler with a mysterious backstory and a stolen identity. Unlike Frank Wheeler, who romanticizes the past and likes to hear himself talk, Don Draper says little and romanticizes nothing, not unlike Parker. Take away Parker’s gun, give him a job in advertising, a wife and two kids, and move him to the suburbs, and you have, essentially, Don Draper.

In the opening of The Hunter, as Parker is crossing the George Washington Bridge on foot, we see all those faceless “grey flannel” mass commuters heading into the city. Stark divides these commuters into the “office men” and the “office women.” When the men see Parker, if they see him at all, they think he’s a bum. The women, on the other hand, recognize his raw sexuality. The sight of him scares them, it makes them thankful for their husbands, and yet they’re still intrigued and drawn to him.

What makes Parker an inverted “man in grey flannel” is that, though he lives in the same world with these men and women and acknowledges their existence, he has never been a cog in their corporate wheel. For Parker, these cogs aren’t just advertising executives or the secretarial pool, either. The vast criminal enterprise of the Outfit also epitomizes the corporate world. Not a legitimate one, mind you, but one that represents—at least in Parker’s mind—the status quo. There’s a pecking order; the daily grind; all the accompanying BS. These are the “suits,” as it were. And this is why, we surmise, Parker is a crook—so as not to be one of them. (Apparently, before his wife and buddy tried to kill him, Parker would live comfortably in a nice hotel until the money ran out, at which point he’d start putting together a new heist. You get the distinct feeling that the heists had less to do with the acquisition of material wealth than with not having to keep a nine-to-five job.)

And so, with either great disdain or indifference, Parker spits at the passing cars and continues his walk into Manhattan. Here again, the Frankenstein simile is not too far off the mark:

[Parker’s] hands, swinging curve-fingered at his sides, looked like they were molded of brown clay by a sculptor who thought big and liked veins. His hair was brown and dry and dead, blowing around his head like a poor toupee about to fly loose. His face was a chipped chunk of concrete, with eyes of flawed onyx. His mouth was a quick stroke, bloodless. His suit fluttered behind him, and his arms swung easily as he walked.

Parker is almost literally the risen dead as he lurches into Manhattan, and his presence has the most unsettling effect on those who see him, especially women because he reciprocates none of the attention that they give to him. After a counter girl lights a cigarette for him, “leaning over the counter toward him with her breasts high, like an offering,” Parker drops a dime onto the counter and leaves without a word.

[The counter girl] looked after him, face red with rage, and threw his dime into the garbage. Half an hour later, when the other girl said something to her, she called her a bitch.

Throughout these three books, and especially in The Hunter and The Outfit, both of which focus more on retribution than The Man with the Getaway Face does, Parker appears as an automaton or a robot, more machine than human, always in perpetual motion, even as those around him screw up the simplest of plans. A recurring theme in the Parker books is that if something can go wrong, it will. Human error is pretty much always the root cause, and Parker has to suffer through the idiocy of one knucklehead after the other, often having to imagine the ways they might mess up before they actually do, just so he can mitigate the damage. This may be the universal truth of the Parker novels and the reason why, even though he’s an unapologetic thief and murderer, we empathize with him. But unlike an automaton or robot, which is often depicted as a machine-man that desires to be human, Parker is a human who wants to be more like a robot. He wants less feeling, not more.

In a particularly telling scene from The Man with the Getaway Face, a slow-witted driver named Stubbs, who’s avenging his boss’s death, seeks out Parker as one of three men likely to have killed him. After it becomes clear to Stubbs that Parker wasn’t the one who killed his boss, Parker decides he needs to keep Stubbs out of sight for a while so that Stubbs doesn’t screw up the heist he’s in the middle of planning. Parker puts Stubbs away in the basement of an old farmhouse, paying him daily visits. When Parker has to be out of town for more preparation, he enlists the help of others. “Walk Stubbs for me,” becomes Parker’s refrain. When his friend Handy notes that Parker talks about Stubbs like he’s a dog, Parker responds, “He’s a pain in the ass.” Later, after Stubbs escapes from the basement, he reflects on why Parker let him keep the flashlight that Parker’s partner, Handy, gave to him:

Parker was impersonal, not cruel. He never did anything without a reason, and there was no reason to taunt Stubbs, so the flashlight was really his. Parker didn’t feel sorry for him because he didn’t feel anything for him at all, with the possible exception of irritation. But Handy felt sorry for him, and that was his break.

Pretty much the only sentimentality Parker exhibits is toward his wife, Lynn, who had been forced to double-cross him. With everyone else, it’s as though he’s programmed to respond a certain way without deviation.

[Parker] wanted to kill [Lynn], to even things, but when he’d seen her he’d known he couldn’t. She was the only one he’d ever met that he didn’t feel simply about. With everybody else in the world, the situation was simple. They were in and he worked with them or they were out and he ignored them or they were trouble and he took care of them. But with Lynn he hadn’t been able to work that way.

When Lynn dies by her own hand early on in The Hunter, the last of any emotion even remotely resembling love dries up in Parker, allowing him to focus laser-like on the three remaining categories of people: those who are with him, those who aren’t, and those who are against him. In this regard, the tone of the Parker novels sometimes borders the cold and eerie post–Apocalypse of certain sci-fi movies, like The Terminator. Even Jim Thompson, who took darkness to new depths, used humor to offset the bleakness surrounding his characters’ lives.

So, where does a writer like Richard Stark fit into the noir canon? The books are entertaining, but some of the dust jacket praise strikes me as unusually hyperbolic. You won’t hear me going so far as to talk about Stark’s “Nabokovian wit and flair,” as Richard Rayner does, or to suggest, as Lawrence Block does, that you should “forget all that crap you’ve been telling yourself about War and Peace and Proust—these are the books you’ll want on that desert island.” No, sorry, I’ll still take War and Peace and Proust. In fact, these early novels are dated in a way that many lesser (and, frankly, bad) noir novels are as well. Women are almost always introduced with a description of their (sometimes “conical and well-separated,” other times “big mounded”) breasts. Effeminate men are “fags.” Minorities are pretty much nonexistent. I would be the first to concede that you can’t read old noir expecting a contemporary, post–PC sensibility. On the other hand, it’s difficult to wind your clock back to 1962 after reading the more complex contemporary crime novels of George Pelecanos or Dennis Lehane and accept Stark’s simpler worldview as enlightening. That said, I’m a forgiving reader, and Stark’s novels are not only entertaining for what they are—midcentury noirs—but they are also better than a lot of what was coming out back then. And let’s face it: the man wrote fast, and like other novels by writers who are this prolific, each book becomes a snow globe of its own peculiar time. (I look similarly at Rex Stout’s novels: a five-decade history of American sensibilities as filtered through a detective series.)

Perhaps the most interesting thing Stark did was place an antihero front and center, as Jim Thompson often did in books like The Killer Inside Me and Pop. 1280, while stripping away layers of internal thought so that the books read more like a Hammett novel of the 1930s than, say, a Chandler of the ’40s or a Ross MacDonald of the ’50s. The result—a ruthless killer with very little meaningful internal thought—is a little unsettling, and though I find this unnerving fusion mostly a strength in the series, I can’t help being reminded of Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s analysis of Othello’s Iago as a “motiveless malignancy.” Parker’s malignancies, such as they are, are not entirely motiveless (after all, his wife shot him and his buddy burned down the building he was in), but this backstory is about as deep as we get into the psychology of the man. And maybe that’s all we need to know. Richard Stark isn’t Shakespeare, and the Parker novels aren’t Othello. In fact, the Parker novels were born out of Donald Westlake’s desire to create another market for himself. In a 1996 interview with Charles L. P. Silet, Westlake explains Richard Stark’s origin:

[T]here’s always been a belief in publishing that [a publisher] can’t publish more than one book a year from any one author. So I thought it would be interesting to have a pen name . . . to aim for a paperback original this time. So I did this book with the assumption that the bad guy has to get caught at the end . . . I sent [The Hunter] to Bucklin Moon at Pocket Books, who said, “I like this book and I like this character. Is there any way you could change the book so that he would escape at the end and then you could give me three books a year about him.” And I said, “I think so.”

So there you have it: the Parker series was an accident. A happy accident for Westlake. Since Westlake wasn’t planning on Parker becoming a serial character, he made Parker “completely remorseless, completely without redeeming characteristics.” Westlake went on in the interview to say, “In a series the guy’s got to be around for years and the readers have to like him. But we came in here with this son of a bitch and we’re going out with this son of a bitch. I felt that he had to remain true to himself.”

Perhaps this, more than anything else, is what I admire most about these novels: the consistent ruthlessness of an unapologetic bastard. And so if you’re a fan of noir novels and haven’t yet read Richard Stark, you may want to give these books a try. Who knows? Parker may just be the son of a bitch you’ve been searching for.