The rest of the world eyes the lives of Golden State tribes—Hollywood “movie people,” surfers, gay San Franciscans, Silicon Valley programmers—with a mixture of fascination and longing. What is the powerful appeal of the California subculture? How have writers, filmmakers, and historians—whether they’re stuck on the outside looking in, or remembering a time they once belonged—tried to explain what it’s like to be part of a California scene?

The rest of the world eyes the lives of Golden State tribes—Hollywood “movie people,” surfers, gay San Franciscans, Silicon Valley programmers—with a mixture of fascination and longing. What is the powerful appeal of the California subculture? How have writers, filmmakers, and historians—whether they’re stuck on the outside looking in, or remembering a time they once belonged—tried to explain what it’s like to be part of a California scene?

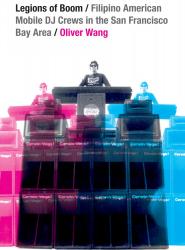

Oliver Wang’s book about the mobile-DJ scene in California’s Bay Area between the late 1970s and the mid-1990s, Legions of Boom, is a microhistory of an obscure subculture. During this decade and change, groups of Filipino-American teenagers living in the suburbs around the Bay coalesced into a party scene very particular to its time and place. “Crews” of mostly male friends—DJs, plus those who put together the physical infrastructure of turntables, lights, and speakers—anchored parties in garages, church basements, and assembly halls. Without the benefit of social media or much coverage in newspapers or on the radio, these mobile DJs assembled a scene: loose networks of people who competed against one another, bolstered one another, and saw one another on the dance floor every Friday and Saturday night. Almost as soon as it began, the scene was over, but the people Wang interviews still remember those days as something extraordinary—an unusual time that defined who they were as a community.

Oliver Wang’s book about the mobile-DJ scene in California’s Bay Area between the late 1970s and the mid-1990s, Legions of Boom, is a microhistory of an obscure subculture. During this decade and change, groups of Filipino-American teenagers living in the suburbs around the Bay coalesced into a party scene very particular to its time and place. “Crews” of mostly male friends—DJs, plus those who put together the physical infrastructure of turntables, lights, and speakers—anchored parties in garages, church basements, and assembly halls. Without the benefit of social media or much coverage in newspapers or on the radio, these mobile DJs assembled a scene: loose networks of people who competed against one another, bolstered one another, and saw one another on the dance floor every Friday and Saturday night. Almost as soon as it began, the scene was over, but the people Wang interviews still remember those days as something extraordinary—an unusual time that defined who they were as a community.

The Fast and Furious movies—there are seven in total, produced between 2001 and this year—are a huge cultural phenomenon that’s spectacularly financially successful. While it can be hard to remember, given the way the later installments have bloated beyond recognition, the films began modestly, with another tiny California subculture at their heart. The first installment is about a golden-boy undercover police detective, Brian O’Conner (Paul Walker), who infiltrates an illegal street-racing scene in Los Angeles while trying to solve…some crime or another. The point of the movies is the racing itself, and the group of attractive driver-criminals led by Dominic Toretto (Vin Diesel), a transcendentally authentic and powerful figure whose influence acts (as his sister Mia puts it) “like gravity” on those around him. Over the course of the series, O’Conner, always an ambivalent officer of the law, leaves mainstream culture for this subculture; he finds his true love, true family, and true self in the process.

The mobile-DJ scene and the street-racing scene evoke strong emotions: the sensation of mastery, the love of a chosen community, and the feeling of joyful escape from the routines of everyday life. On the one hand, we have a series of candy-colored, laughably unrealistic movies that draws incredibly loyal audiences; on the other, an earnest book, written to academic standards, that takes its duties of reporting and interpretation very seriously. Neither approach to representing a subculture can quite satisfy the onlooker’s insatiable desire to be there: to be part of what happened. Maybe it’s in the very impossibility of satisfaction that the lure of the subculture can be found.

The group dynamic of a subculture, amplified by the sun and utopianism of the California dream, forms the core of the narrative appeal of the Fast and Furious movies. The camaraderie on display is far overdrawn—Toretto is forever making heartfelt toasts to “family” at the end of backyard barbecues—but it’s also a powerful force, defining the difference between these racing people and the everyday world around them. Every Fast and Furious movie needs to have a street-race scene, which shows how racing fans (75 percent of whom seem to be scantily clad women) are able to assemble an illegal party out of nothing, making a parking garage or an anonymous bridge into a stage set for their own temporary social world.

The Fast and Furious car-racing subculture defines insiders and outsiders by strict terms, putting a premium on loyalty and like-mindedness. In 2 Fast 2 Furious, O’Conner and the crew’s comic relief, Roman Pearce (Tyrese Gibson), are escaping police pursuit, and they call upon Tej (Chris Bridges) to help them out by providing cover. This setup leads to one of the funniest spectacles of the series: Brian and Roman drive into a garage with multiple bays, and a clutch of police cars draws up outside, convinced that they have the runaways cornered. When the garage doors go up, a scramble of brightly colored cars emerges—a flood beyond preposterous in its dimensions. (How did all of those cars fit in that garage? The volume suggests a silo of parking levels underground.) The police are quickly overcome, and there is no way that they can identify their suspects. Brian and Roman are literally hidden by their friends—given camouflage and aid by those around them who believe as they do.

One of the most interesting revelations of Wang’s book is the degree to which Filipino-American DJ crews were also embedded in their own communities—not just youth communities, but the entire social world of Filipino-American suburbs of the Bay Area. If Fast and Furious drivers are outlaws, living parallel to a world of law and order, these mobile crews were a subculture inside a strongly determined ethnic world. The DJs had the approval of Filipino-American parents, who liked to see their sons start businesses, and there were plentiful gigs available because the intergenerational Filipino-American community liked to get together and dance. Crews were “informal families, fraternal organizations, cliques of like-minded peers,” and they worked together like entrepreneurs, drawing on the resources of their networks of family and friends to get work.

At the center of the wild swirl of the party or race—the crowded floor of dancers; the vehicle vibrating with speed—the man of the hour, be he driver or DJ, experiences a moment of transcendent masculine control. Wang describes the connection between DJing and mastery of the body. “Some DJs may be very physical in their performances,” Wang writes, “but their movements are often subtle, meant to look meticulous, deliberate, and finely controlled.” The perfection of this illusion is part of the point. “If the ideal posture of a rock guitarist is captured in overt spectacle,” DJs are “meant to stay in cool, collected control so that everyone around them can abandon themselves to the music.” The man in charge is the still point, executing everything perfectly, “going for it” as onlookers lose their minds. It’s this young man and his crew, Wang writes, who would receive the scene’s honorific, “party rocker.”

The “party rocker” was rarely a young woman. “Crews themselves were overwhelmingly male in composition,” Wang writes. “Their very formation as male, homosocial organizations was…part of their organizational appeal.” Female attendees at parties were important—their presence is mentioned by many of Wang’s interviewees as a key incentive to start spinning records—and women worked both formally and informally as promoters and clients of the various crews. One of Wang’s most interesting findings is that mobile DJing was a family affair for the Filipino-American community: Mothers and aunts regularly found gigs for their younger male relatives, or floated them money to buy equipment. Still, the DJ was the center of attention, and his actions were the ones to watch.

Michelle Rodriguez’s tough racer Letty Ortiz and a few scattered (extremely pretty) female racers aside, the Fast and Furious fantasy is also one of male control. Dominic Toretto is the ultimate rock, a man so impassive that he barely smiles or reacts, even when he finds out about Letty’s supposed death in Fast & Furious, or when he wins a race or pulls off a heist. Vin Diesel’s ex-bouncer physique and his quasi-immobile face are perfectly adapted to convey the impression of complete control in the face of chaos. He and O’Conner succeed in dominating the race scene because of their lack of fear. Later in the franchise, when the crew begins pulling off heists, Toretto stands at the center of an impossible series of plans, pulling strings and making demands even when his crew begins to doubt that it’ll succeed. Of course, it always does.

The third movie in the Fast and Furious series, Tokyo Drift, a box-office fiasco and critical dud, is underrated. Part of the reason I like it is that its hero—Sean Boswell, played by Lucas Black—is a classic ugly American, an uncomfortable white guy who fails miserably when he tries to race cars in Japan, where the style in the underground scene is to “drift” sideways around complicated race courses. Boswell has to work to earn the easeful control that O’Conner and Toretto exhibit in every race without even trying. Of course, in the end Boswell succeeds, regaining the masculinity that he has momentarily lost, but there’s a learning curve that lends the movie variety among its fellow franchise installments. This, too, is something that’s missing in Wang’s book, in part because it’s trying to analyze a scene ethnographically, rather than describe it narratively. I want to see how mobile DJs learned their trade, joined in their failures, and celebrated their successes.

The ephemerality of subcultural scenes seems to be directly related to their tantalizing transcendence of the “real world.” The mobile-DJ scene that Wang describes dissolved through a number of natural processes, one of which was that the people who participated enthusiastically as teenagers and young adults eventually needed to get real-world jobs. DJing moved toward a style that was more focused on single performers, and the “crew” was no longer necessary; younger people coming up in the Filipino-American community gravitated toward other scenes. (Wang’s interviewees, when asked why the culture around mobile crews declined in the early 1990s, offer the advent of the import-car scene among Asian-American teenagers in California as one reason. “About 95 percent of the mobile crews that I was aware of in my generation—as soon as they got their Honda, it was over,” said respondent DJ Pone.)

Audiences viewing Furious 7, the latest installment in the franchise, cried at the final montage, which was an homage to the actor Paul Walker (who died in a high-speed car crash in Santa Clarita, California, while the film was in production). I cried, too. The core Fast and Furious crew, which stuck together as actors aged (and characters along with them), had seemed permanent in a way that real subcultural groups rarely get to be. The fact that this permanence was fictional, and obviously forced in order to eke out box-office dollars, mattered little; you still felt a little thrill of joy when the team reassembled, stepping out of their beautiful cars one by one. Tej, the smart one; Roman, the funny one; Brian, the golden one; Dom, the center.

In an interview with Vibe on the occasion of Furious 7’s release, Rafael Estevez, the former New York street racer and subject of the Vibe article that inspired the Fast and Furious movie franchise, explained why he had stopped driving: “I had a lot going—a wife, kids, a business. I had more to lose than when I was by myself.” (Like the Fast and Furious character Tej, Estevez parlayed his former extralegal activities into legal entrepreneurship; he now owns a shop in Queens called DRT Racing.) The movies had just begun to figure out how to balance the fact that Mia and Brian had had a child with the need to have O’Conner out there, driving off of cliffs and shooting at bad guys. Walker’s death ensured that O’Conner wouldn’t fade into domesticity and middle age, piloting only a minivan; at the end of the movie, the character literally drove off into the sunset, putting a close on the scene as it was.

Wang includes a few pages at the end of his book noting future directions for more research on the mobile-DJ community. Among his mea culpas: He barely talked about the kinds of music the DJs played; he thought he could have written more about postcolonialism in relation to the Filipino-American community; he could have done more to connect the mobile-DJ scene to the Filipino involvement in competitive dance crews and ROTC drill teams, and to other hip-hop practices like B-boying, graffiti, and MCing. The point of including those “future directions” pages in a scholarly book is clear; it’s a good way to cover yourself against critiques. It’s also dangerous. I finished the section and immediately thought to myself, Yes! I would like to read the book that includes all of that.

But it’s not because I think Wang’s scholarship is thin. I just want more detail. I want to know what it was like to be there. What were people listening to, how did their bodies move, what did it all look like? It’s not Wang’s fault that he’s writing an academic book about partying for a reader who just wants to be on the dance floor at a garage party in Daly City, circa 1986, feeling everyone I know go wild around me. For people who weren’t there, a representation of a subculture may always be a bittersweet and compelling thing.