Disgrace is a public phenomenon, defined by public measures—of perception, opinion, consensus. To suffer disgrace is to arouse a collective sense of betrayal, bounds demolished, moral or social compacts violated. Reprieve from disgrace is also a public phenomenon, something a certain kind of documentary makes plain. Having suffered disgrace, occasionally a public individual will sit for a documentary portrait, as both former New York congressman Anthony Weiner and Laura Albert, the writer behind the literary persona JT LeRoy, have recently done. Weiner and Author: The JT LeRoy Story apply documentary means to restorative ends, where a kind of suspense attends the effort to marry a frayed reputation to a private self, disgraceful behavior to mitigating context, image to some more tangible thing.

Disgrace is a public phenomenon, defined by public measures—of perception, opinion, consensus. To suffer disgrace is to arouse a collective sense of betrayal, bounds demolished, moral or social compacts violated. Reprieve from disgrace is also a public phenomenon, something a certain kind of documentary makes plain. Having suffered disgrace, occasionally a public individual will sit for a documentary portrait, as both former New York congressman Anthony Weiner and Laura Albert, the writer behind the literary persona JT LeRoy, have recently done. Weiner and Author: The JT LeRoy Story apply documentary means to restorative ends, where a kind of suspense attends the effort to marry a frayed reputation to a private self, disgraceful behavior to mitigating context, image to some more tangible thing.

If rehabilitation is the A story, in both films a B story emerges to dog and eventually overthrow it: Weiner, forced out of public office by a sex scandal (involving his habit of engaging women on social media, communications that often escalated to include graphic images of his genitalia), suffers another one (more strangers, further images) in the midst of a comeback mayoral campaign; chirping on her confessor’s perch, Albert simply continues to speak, a more confounding, thwarted figure with each expository breath. But rather than altering the viewer’s relationship to clemency-seeking portraiture, the triumph of story B only enhances the experience central to the rehabilitative doc, by which the viewer is courted, her good judgment invoked, her sense of moral deliberation flattered. It is she who puzzles, relates, and perhaps forgives. It is she who extends good faith and is rewarded for her efforts. It is her access to grace, and not the subject’s, that matters as the credits roll.

Near the end of Weiner, Josh Kriegman and Elyse Steinberg’s raucous, arresting study of Anthony Weiner’s 2013 run for mayor of New York City, the candidate is sullen, resigned about what he’s done. In that moment, what he regrets is not the behavior that tanked his campaign, but the fate of the project that wound up documenting the whole gruesome affair. “The laws of entertainment gravity are going to suck the documentary into the same vortex,” Weiner laments—the vortex that first opened in 2011, when Weiner accidentally posted a graphic photo of himself, meant to be shared privately with a follower, to his own public Twitter account. “I wanted to be viewed as the full person that I was,” Weiner says of agreeing, with the documentary, to invite yet more scrutiny of himself, his then wife (Hillary Clinton aide Huma Abedin), and their young son. “Maybe that was naïve too.”

To the extent that Weiner presents us with Anthony Weiner, man in full, it does so by tracing the psychic fault lines that keep blowing his life open. The eradication of those lines feels central to the film’s idea of Weiner—that there is no discernable distinction between the public and private man is not a flaw in the thing but the thing itself. If Kriegman and Steinberg set out to find a “real” Anthony Weiner, to “humanize” a walking punch line, they discovered a radical challenge to their premise: a creature who grows more enigmatic with exposure, who is made of image and hunger, a hologram of desire who, in blurring before our eyes, communicates something almost unbearably human.

To see Weiner is to see double. He is outsider and insider, contender and pariah, string bean and gym bro, family man and freewheeling sexter, Congressman and Carlos Danger (Weiner’s online alter ego). Even Weiner doubles Weiner, interspersing vérité footage of a candidate in manic campaign and then crisis mode with clips from a later sit-down interview that finds Weiner chastened, thoughtful, and prone to frequent, exquisitely timed pulls on a coffee mug. What he is consistently—and what makes him an almost unnaturally natural documentary subject—is game. Even shutting down one of Kriegman’s intrusive (certainly vis-à-vis the vérité playbook) questions, Weiner manages to cooperate: In chastising the director for being a fly-on-the-wall who won’t shut up, he creates a complex and genuinely funny moment.

Similarly edifying are scenes of Weiner on New York City’s streets and inside its dun-colored public halls. A woman clamors beside Weiner as he mounts a Citibike—should she know him? Why the camera? “He’s Anthony Weiner,” a passing man announces, trailing a disgusted mix of knowing and indifference as he hustles to make the light. Other New Yorkers shout support, offer admiring words; still others demand a symposium on his character; one, a man in a Jewish bakery, insults Abedin. Brooklyn-born, Weiner takes it all, engaging supporters, exhaling in the face of piety, dancing in parades, and battling helplessly with the man in the bakery. Disgrace grants Weiner the opportunity to exploit as never before his unprejudiced need for attention.

It’s a striking thing to behold. Weiner’s scolding of the media and attempts to focus attention on his political platform convince no one. The campaign is pure theater, the punk-rock Democrat shown early in the film—ranting, pounding, and abusing the mic on the House floor—having entered the contrite, post-rehab phase of his career. The humiliation it would entail was built into Weiner’s choice to run for mayor; in many ways his ritual mortification was the point. But the controlled, cleansing fire he sought blazed wild, and in Weiner he emerges from that fire not a laundered public figure but a sort of lurching, ultimate political animal.

Weiner built a reputation holding himself above politics, arguing relentlessly for the moral choice over the political or procedural one. Despite sparing little for Weiner’s political agenda, Weiner is very much about politics, as in some respects every character study must be. It’s about the politics of a marriage, certainly: Weiner is to a great extent a film about Abedin’s face. Her fragile, weary dance between belief and doubt, hope and disappointment, evident in her large, staring eyes, holds the viewer spellbound. A different political dance animates the aides and advisers who fret, pout, and scuttle, locked in a predicament somehow best expressed by the interminable flow, the ferrying and consumption of various juices, cigarettes, sandwiches, and Starbucks drinks.

Weiner falters in prodding its subject with a question whose asking involves too certain a pleasure: What is wrong with you? After pointing out the disingenuousness of the question, Weiner eventually attempts an answer by way of self-analysis. It’s a brief interlude, colored with therapeutic language, a theory about Weiner’s fatal attraction to the superficial, transactional relationships that are the stuff of both politics and social media, that is, “the technology that undid me.” It is perhaps the least interesting moment in an otherwise riveting film, precisely because it engages in a form of documentary politics, wherein the identification and accounting for a subject’s pathology constitutes drama, and drama’s resolution. It takes leave of the more apt question of what we might learn, through further exposure, about a man famous for exposing himself. It ignores everything wrong with a question like What is wrong with you?

More persuasive is Weiner’s answer to yet another of Kriegman’s questions. Standing in his living room, Weiner is entranced by a lurid TV-news report about himself. Abedin sits nearby, eating, seething. The politician who trafficked in realness, in cutting through, appears trapped in his own home, his image on one side, a camera on the other, his mortified wife behind. We hear a voice: “Why have you let me film this?” Agape, Weiner turns, a picture of defeat. He shrugs; he turns back to the TV.

The telephone is central to the story of how Brooklyn native Laura Albert invented and perpetrated the myth of her literary alter ego, a West Virginian teenage hustler and drug addict she named JT LeRoy. “I would get to a point where I would have to make a call,” Albert says in Author: The JT LeRoy Story, describing the suicidal depression that led her to pretend to a therapist that she was a messed-up kid named Crash. It was a habit she developed as a child, when, in the midst of her parents’ divorce, an idea first occurred to her: I want to call a hotline and be a boy in trouble. Who would care, anyway, about a fat, disgusting, ordinary girl?

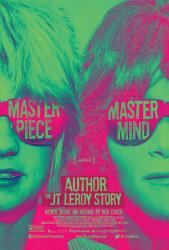

From those first calls, Albert learned that the terms of her story mattered, that the attention she might elicit stood in direct correlation to the way she packaged her pain. She planned and adjusted accordingly. Those terms, and the response they excited, eventually led to the most fascinating literary hoodwinking of our time. Director Jeff Feuerzeig’s documentarydoesn’t have much to offer those seeking a critical postmortem of that affair: Author is more oblique and full of misdirection than seems possible given a project this bent on explaining, and perhaps vindicating, its subject.

The frustration this entails feels essential to an understanding of Albert, who effectively narrates Author, a talking head in leather and chains, seatedagainst a backdrop of text, it appears, taken from the LeRoy novel Sarah. Albert’s dominatrix-punk styling cuts against her tendency to breathless self-drama and cliché (following the success of Sarah, “a message in a bottle to the world,” its fake author, LeRoy, “had to walk amongst us”). As her long confession continues, however, Albert’s outfit and her affect begin to make sense together, a study in paradox, in earnest contrivance.

Author suggests the extent to which Albert’s attraction to punk—its mythologies of truth and rebellion—seemed to warp permanently her relationship to herself and to the rest of the world. On first hearing the likes of Stiff Little Fingers, she says, “my fate was sealed.” Desperate to join the New York punk scene but unfit for what she saw as the part, Albert dressed her sister and sent her out to shows; she faked a British accent to lure a punk boyfriend. The antiestablishment, it turns out, has plenty of rules, most of which amount to a series of poses. Albert grasped this intuitively. She knew that style and context could unseat and even become substance. Postures of nihilism, free expression, and inclusivity aside, she knew that “there’s nothing worse than being a fat punk.”

There is also no LeRoy without the response to him. Albert used the persona that drew sympathy and support from her therapist, and the writings that came out of that therapy, to attract the attention of writers like Dennis Cooper and Bruce Benderson, and eventually an agent and publisher. The subject matter was dark, full of drugs, self-destruction, and abuse; it was punk, in other words, and supposedly drawn directly from life. The publishing community and then a platoon of artists and celebrities rushed to align themselves with this perfect, final, millennial avatar of everything punk held dear and corporations made saleable. Author opens with footage of a gushing, incoherent Winona Ryder introducing LeRoy (Albert eventually enlisted her androgynous sister-in-law, Savannah Knoop, to play the character in public) and his “beautiful, beautiful voice” to a crowd. “I love you JT,” Ryder says, “you are an inspiration.”

Agent Ira Silverberg appears in both Author and Marjorie Sturm’s 2014 documentary The Cult of JT LeRoy. In the latter film, Silverberg declares that his former client’s writing is ultimately remarkable only in the context of LeRoy’s mythology. “It was work that was published because it was supposed to be the authentic voice of someone who suffered.” But most authors have suffered, being (mostly) human, and all might be said to seek an “authentic voice.” It was Albert’s exact calculations that led Silverberg to place LeRoy in a distinctly male lineage that includes Jean Genet and William Burroughs, those authors who “kept us thinking about a certain kind of darkness and a certain kind of pain.” It was her canny that besotted a Bloomsbury editor, who describes publishing LeRoy, “this wounded creature,” as a form of “pleasurable altruism.”

Although it goes further than Author in its interrogation of the cult that effectively created LeRoy, Sturm’s film ponders with greater interest the question of just what is wrong with Laura Albert. Is she evil? A sociopath? Insane? One observer refuses to grant her the “romance” of mental illness; another derides Albert’s postmortem attempts to frame LeRoy as the ultimate punk-rock move. “I came out of the punk scene,” Albert said in 2010. “I had that punk energy.” No one told her she couldn’t “write fiction and use a persona and have someone else play the writer.” And even if they did, “I’m a punk—yes I can!”

Author offers a sort of response to The Cult of JT LeRoy, specifically in its emphasis on backstory (Albert describes early childhood abuse and her time as a ward of the state) and on the writing, some of which forms the basis of striking animations, all of which Albert reads in the same gender-neutral drawl we hear on the many, many taped phone conversations she conducted as LeRoy. The existence of those tapes is a puzzle Author doesn’t touch, a symptom of the film’s failure to reckon with Albert as a person of agency. Rather than interrogating her motives, Feuerzeig presents audio of Tom Waits, Mary Karr, and Gus Van Sant as evidence in Albert’s favor. Even the cool people aren’t above a good con, the framing suggests, and for good measure here’s Courtney Love pausing the conversation to blow a line of coke.

Albert habitually slips into a passive voice in Author: Things come to pass. Books get written. Voices move through her. She is there but not there. Wide-eyed, Albert marvels over it all. She is inscrutable describing the hysteria an incomprehensible LeRoy inspired in an Italian audience (“It was perfect”) and giddy recounting the moment Bono treated LeRoy to “the Bono talk,” a primer on celebrity. It’s not outright gloating one seeks—but the film’s lack of a critical, considered perspective on the madness, some persuasive idea of Albert and her coup, leaves the viewer feeling had. Our narrator exits Author not a bowing maestro or figure of great, unresolved fascination, but a mushy sort of character, to whom some extraordinary things happened.

Albert appears most sincere in her moments of defiance: “The book says—clearly, on the jacket—fiction,” she says. “The rest is extra.” But the extra is no small thing; the rest entails a hunger so vast even Laura Albert’s endless appetites couldn’t match it. We live in a time of extra, as Albert discovered and as the success of JT LeRoy confirms. We live according to the laws of entertainment gravity. Had he been able to remain a voice on the telephone, JT might still exist today—a boy in trouble reaching out, flattering his heroes, telling his story, accepting their flattery in return. The rest was extra.