Walt Whitman was fascinated with photographic images of himself. From the 1840s until within a year of his death, Whitman sat for photographers, collected and commented on the results, admired certain poses and disliked others, had hundreds of copies of his favorite ones made, tolerated the middling ones, and burned some of the bad ones. He would often comment that photography was part of an emerging democratic art, that its commonness, cheapness, and ease were displacing the refined image of art implicit in portrait painting. Painted portraits were for the privileged classes, and even the wealthy did not have their portraits painted regularly; the one or two they had done over a lifetime had to distill their character in an approximation that transcended time. But photographs were the property of all classes, and they allowed people to track their aging accurately, to watch themselves change step by step as they grew old. Photographs tracked a life in time and demonstrated that life was a process of continuity and change.

No author’s life in the nineteenth century was more continuously photographed than Whitman’s. “No man has been photographed more than I have,” he once said. At times he seemed fatigued with the profusion of images: “I have been photographed, photographed, photographed, until the cameras themselves are tired of me.” Whitman, however, never tired of the camera. He sat for photographs until just months before his death. Long after he had ceased to write poems, he allowed photographers into his Camden home. In those dwindling days, Whitman pored over his uncollected manuscripts commenting on them for his dutiful admirer and soon-to-be executor, Horace Traubel. When he would happen upon a photograph among the sea of scrap paper, he would pause and ponder the expression of those younger selves. He would ask Traubel his opinion, if he thought one was too stiff, “a little too much up and down,” or say of another, “It’s a little rough and tumble, but it’s not a face I could hate.” Once, looking at the hopeless clutter of photographs, unable to identify the dates and circumstances of many of them, Whitman lamented, “I have been photographed to confusion. . . . . I’ve been taken and taken beyond count.” Stumbling upon photos of himself he had forgotten had been taken, he joked, “I meet new Walt Whitmans every day. There are a dozen of me afloat. I don’t know which Walt Whitman I am.”

This “confusion” of Whitman’s, this jocular identity crisis, often turned more serious as he thought about what all these images over the years suggested about the wholeness of his life: “It is hard to extract a man’s real self—any man—from such a chaotic mass—from such historic debris.” While he knew that “the man is greater than his portrait,” he also knew that his photographs over a lifetime were adding up to something, were capturing a persisting quality that had never before been seen in human experience: “The human expression is so fleeting—so quick—coming and going—all aids are welcome.” He carefully read and interpreted his photos, looking for clues to their individual and momentary significance, looking for ways the single images added up to a totality: “I guess they all hint at the man.” Most of the photos, he believed, were “one of many, only–not many in one,” each picture an image that was “useful in totaling a man but not a total in itself.” In a poem he wrote about a photograph, Whitman referred to the image of his face as “This heart’s geography’s map,” and as he examined his photographs, he tried to read them like a map–a series of visible shorthand signs cast on paper that would guide him to the nature of his invisible heart.

Note: This text and the passages accompanying the photos in this issue are adapted from the gallery section of the Walt Whitman Archive, compiled by Ed Folsom and Ted Genoways.

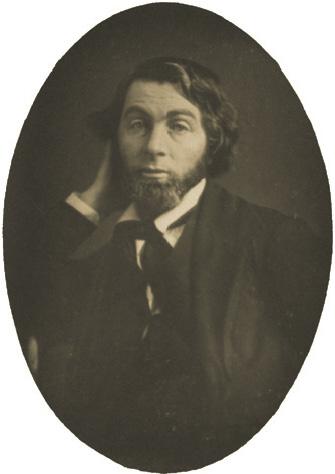

The New Orleans Daguerreotype

For more than a century after Whitman’s death, almost nothing was known about this early and beguiling daguerreotype portrait. Many scholars had conjectured that this image–with Whitman posed in a formal frock coat and black cravat, his hair gray only at his chin and in a single shock atop his head–must derive from the early 1840s, during Whitman’s days as editor of the New York Aurora. In 1991, however, Denise B. Bethel examined the case in which the portrait is held and discovered that the paper seal holding the image in place is made from “what appears to be newsprint, in French, with the running head Le Messager fortuitously preserved.” Le Messager was a weekly bilingual newspaper published in Bringier, Louisiana, just upriver from New Orleans, between 1846 and 1860. That tiny scrap proved that this was a portrait of Whitman taken during his brief stint as editor of the New Orleans Daily Crescent between February 25 and May 25, 1848.

Thus, we see, in this portrait, the face of the twenty-eight-year-old editor, far from home for the first time. Whitman found New Orleans exhilarating and was fascinated especially by its free intermingling of cultures and languages. But this was also where he first witnessed the horrors of a slave auction–an experience that he would later incorporate into the poem best known as “I Sing the Body Electric”:

I help the auctioneer . . . . the sloven does not half know his business.

Gentlemen look on this curious creature,

Whatever the bids of the bidders they cannot be high enough for him

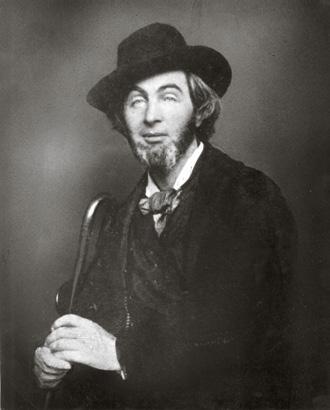

An Unknown Daguerreotype

This image derives from a lost daguerreotype. Without the original, dating is difficult, but judging by Whitman’s appearance–his beard grayer than in the New Orleans portrait–this portrait probably derives from the period between 1849 and the early 1850s. This shadowy time in Whitman’s biography is sometimes referred to as his “Travelling Bachelor” era–after a series of short essays, “Letters from a Travelling Bachelor,” that he wrote for the New York Sunday Dispatch between 1849 and 1850 under the pen name “Paumanok.” The first essay of the series concludes with Whitman extolling the virtues of beards, writing that a “full-whiskered grizzled old chap” who worked on a fishing boat had informed him that “an application, while out there, of the razor or shears was equal to aches,” and the only defense against cold and illness “was to let their beards and hair grow.”

But much more than Whitman’s hairstyle was changing in 1850. In the spring of that year, he vented his anger at Daniel Webster, a longtime abolitionist who had come out in support of fugitive slave laws in March. For reasons we can only guess, however, Whitman unleashed not a scathing editorial, but a blunt, free-verse poem that likened Webster to Judas. Entitled “Blood-Money,” the poem appeared in the New York Tribune on March 22. On June 14, he published a similar poem in the Tribune, entitled “The House of Friends,” in which he urged: “Virginia, mother of greatness, / Blush not for being also the mother of slaves / You might have borne deeper slaves– / Doughfaces,” a derisive term for Northerners who were “like dough” in the hands of Southern slaveholders. And a week later, he published a third poem in the Tribune, entitled “Resurgemus.” Though equally critical, the poem ended on a note of optimism:

Liberty, let others despair of thee,

But I will never despair of thee:

Is the house shut? Is the master away?

Nevertheless, be ready, be not weary of watching,

He will surely return; his messengers come anon.

These were the first lines ever published of what would later become Leaves of Grass, and they were the last that anyone would read by Whitman until he dramatically reemerged in 1855 as “an American, one of the roughs, a kosmos.”

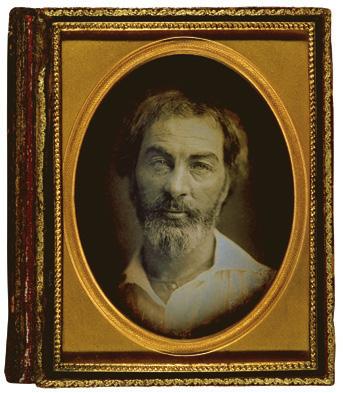

The Christ Likeness

Whitman’s friend Dr. Richard Maurice Bucke called this quarter-plate daguerreotype “the Christ likeness,” and saw signs in it of Whitman’s illumination, the “moment this carpenter too became seer … and he saw and knew the Spirit of God.” Whitman remembered less lofty circumstances under which the portrait was taken in the summer of 1854. He told Horace Traubel:

I was sauntering along the street: the day was hot: I was dressed just as you see me there. A friend of mine–Gabriel Harrison (you know him? ah! yes!–he has always been a good friend!)–stood at the door of his place looking at the pas-sers-by. He cried out to me at once: ‘Old man!–old man!–come here: come right up stairs with me this minute’–and when he noticed that I hesitated cried still more emphatically: ‘Do come: come: I’m dying for something to do.’ This picture was the result.

Despite these humble beginnings, the portrait appears to have been used to help create the frontispiece of the 1855 edition of Leaves of Grass and, as such, remains one of the most iconic images of Whitman–taken in the prime of his youth and less than a year before the publication of his seminal work.

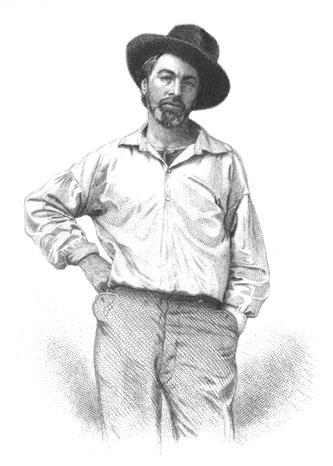

The 1855 Frontispiece

The first edition of Leaves of Grass appeared with no author name on the title page, so readers had only this image by which to identify the author. For its era, it was shocking. Readers were used to formal portraits of authors, usually in frock coats and ties. Very often they were posed at reading tables with books spread open before them or holding a thick volume in their hands. The rebellious, open-collared pose presented here was designed to stand in stark contrast. The first review in the New York Tribune proclaimed:

From the unique effigies of the anonymous author of this volume which graces the frontispiece, we may infer that he belongs to the exemplary class of society sometimes irreverently styled “loafers.” He is therein represented in a garb, half sailor’s, half workman’s, with no superfluous appendage of coat or waistcoat, a “wide-awake” perched jauntily on his head, one hand in his pocket and the other on his hip, with a certain air of mild defiance, and an expression of pensive insolence in his face which seems to betoken a consciousness of his mission as the “coming man.”

Many years later, Whitman worried the frontispiece was too audacious. “The worst thing about this,” he told Horace Traubel, “is, that I look so damned flamboyant–as if I was hurling bolts at somebody–full of mad oaths–saying defiantly, to hell with you!” Some of Whitman’s friends agreed; William Sloane Kennedy, for example, hoped “that this repulsive, loaferish portrait, with its sensual mouth, can be dropped from future editions, or be accompanied by other and better ones that show the mature man, and not merely the defiant young revolter of thirty-seven, with a very large chip on his shoulder, no suspenders to his trousers, and his hat very much on one side.” Nevertheless, it remains the defining image of Whitman–and appeared in the 1855, 1856, 1876, and 1881 editions of Leaves of Grass. The portrait is included here among the photographs of Whitman, because the engraver, Samuel Hollyer, wrote that “it was taken from a daguerrotype [sic],” probably by Gabriel Harrison–note the similarity of the collar to the one in the Christ likeness. However, there is ample reason to doubt the engraving’s faithfulness to the original, since Hollyer also described the daguerreotype as “difficult to work from” and admitted to completing the frontispiece with the help of “several sittings from Walt Whitman.”

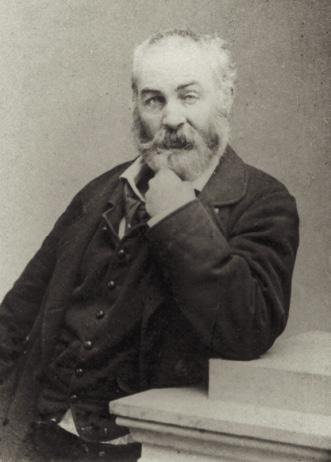

The Black Photograph

This rugged, footloose portrait was taken by James Wallace Black, of Black & Batchelder, in March 1860, when Whitman was in Boston to oversee the typesetting of his 1860 edition of Leaves of Grass. Black’s studio at 173 Washington Street was less than a block from the publishing firm of Thayer & Eldridge, who apparently commissioned the photograph to promote the 1860 edition. The New York Illustrated News, for example, used the portrait as the basis for the engraving of Whitman that appeared with its review of Leaves of Grass on June 2, 1860. Another photograph from the same session with Black shows Whitman seated in profile, but Whitman appears to have rejected that pose, as only three copies are known.

Later in life, Whitman came across this photograph but couldn’t remember the circumstances under which it was taken. Still, he liked what he saw, exclaiming, “How shaggy! looks like a returned Californian, out of the mines, or Coloradoan,” and he was impressed with “its calm don’t-care-a-damnativeness–its go-to-hell-and-find-outativeness.” Even at the time, Whitman seems to have enjoyed the spectacle he created, especially on the streets of Puritan Boston. Writing in 1860, Whitman told a friend, “I create an immense sensation in Washington street. Everybody here is so like everybody else–and I am Walt Whitman!–Yankee curiosity and cuteness, for once, is thoroughly stumped, confounded, petrified, made desperate.”

The Gardner Session

On December 16, 1862, Whitman, while poring over the lists of wounded at Fredericksburg printed in the New York Herald, spotted the name of his brother George, a lieutenant in the 51st New York Infantry. Whitman rushed to the front, searching the hospitals in Falmouth, Virginia, across the Rappahannock River from the Fredericksburg battlefield. He was met by grisly scenes of human carnage–dead bodies laid out on stretchers and “a heap of amputated feet, legs, arms, hands, &c., a full load for a one-horse cart.” He found George alive and well, having suffered only a superficial facial wound, but Whitman was nevertheless determined to go to Washington, D.C., to volunteer in the military hospitals.

Not long after arriving in the capital, Whitman sat for this session with Alexander Gardner, who had made his name months earlier photographing the dead at Antietam. Whitman later recalled a reporter writing about it that “Whitman had been photographed in his night-dress” (a comment that Whitman said made Gardner “fiery mad”), but he regarded it as “the best picture of all.” Photographer Thomas Eakins agreed. Whitman said that “Eakins likes it–says it is the most powerful picture of me extant–always excepting his own, to be sure.” Looking at the photo, Whitman mused, “How well I was then!–not a sore spot–full of initiative, vigor, joy–not much belly, but grit, fibre, hold, solidity. Indeed, all through those years–that period–I was at my best–physically at my best, mentally, every way.”

The Faris Photograph

In October 1863, Whitman did the unthinkable–he got a haircut. Shortly after, he wrote from Washington, D.C., to a friend, “I have cut my beard short, & hair ditto: (all my acquaintances are in anger & despair & go about wringing their hands).” When Whitman visited New York the following month, his hair was still quite short, and perhaps it was for the purpose of memorializing his unusual coiffure that he visited his photographer friend Thomas Faris to sit for this portrait at Faris and Gray Photographers, 751 Broadway. But more than Whitman’s hair and beard had changed. He was dressing more conventionally now–in suits of dark colors. John Townsend Trowbridge, who had seen Whitman during his wild days on the streets of Boston, was surprised to see the poet “more trimly attired, wearing a loosely fitting but quite elegant suit of black,–yes, black at last!” David S. Reynolds has pointed out that Whitman was part of a movement toward standardized men’s clothing during the Civil War. In general, attire became more formal and tended toward dark, somber colors. Earlier in 1863, Whitman wrote his mother: “I have a nice plain suit, of a dark wine color, looks very well, & feels good, single breasted sack coat with breast pockets &c. & vest & pants,” with which he was wearing “a new necktie, nicer shirts.”

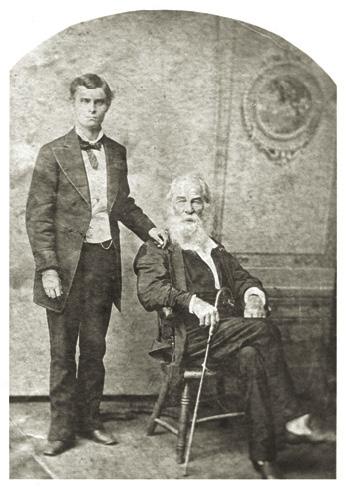

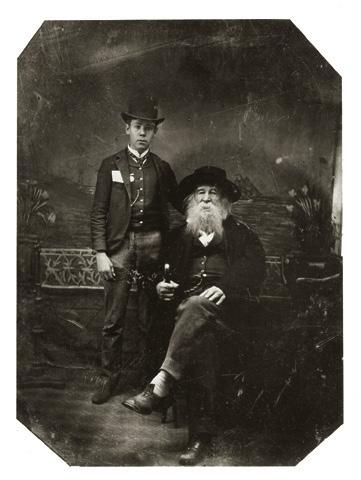

The Doyle Portrait

This is the first extant photograph of Whitman with anyone else. Taken by M. P. Rice in the 1860s, this portrait shows Whitman with Peter Doyle, his lover in Washington, D.C. Doyle was a horsecar driver and met Whitman one stormy night in 1865 when Whitman, looking (as Doyle said) “like an old sea-captain,” remained the only passenger on Doyle’s car. They were inseparable for the next eight years. In 1889, Whitman had a remarkable talk with Horace Traubel and Thomas Harned about the photo; Traubel recalled the conversation:

I picked up a picture from the box by the fire: a Washington picture: W. and Peter Doyle photoed together: a rather remarkable composition: Doyle with a sickly smile on his face: W. lovingly serene: the two looking at each other rather stagily, almost sheepishly. W. had written on this picture, at the top: “Washington D.C. 1865–Walt Whitman & his rebel soldier friend Pete Doyle.” W. laughed heartily the instant I put my hands on it (I had seen it often before)–Harned mimicked Doyle, W. retorting: “Never mind, the expression on my face atones for all that is lacking in his. What do I look like there? Is it seriosity?” Harned suggested: “Fondness, and Doyle should be a girl”–but W. shook his head, laughing again: “No–don’t be too hard on it: that is my rebel friend, you know,” &c. Then again: “Tom, you would like Pete–love him: and you, too, Horace: you especially, Horace–you and Pete would get to be great chums. I found everybody in Washington who knew Pete loving him: so that fond expression, as you call it, Tom, has very good cause for being: Pete is a master character.”

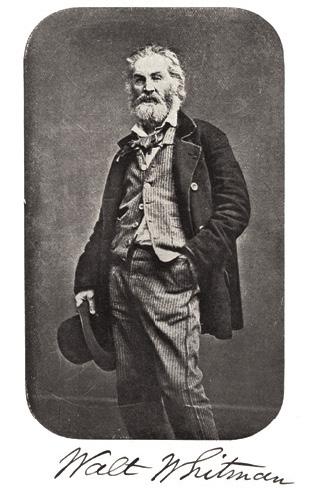

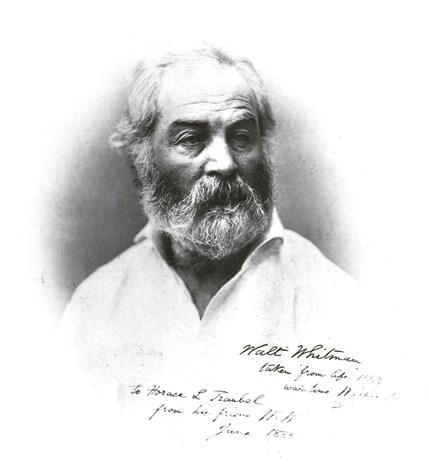

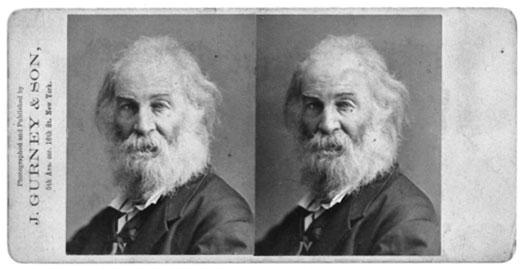

The Gurney Stereocard

This portrait, taken in spring 1871, is one of several known stereoscopic images of Whitman. Like many new technological developments, the prospect of three- dimensional photography intrigued Whitman. In fact, for Christmas 1866, Whitman’s sister and brother-in-law had given him “a small stereoscope,” at which he marveled, you “put pictures in, & look through it, & it magnifies them, & makes them look like the real thing.” This curiosity was still quite new then. Oliver Wendell Holmes had perfected the hand-held stereoscope only seven years before. His invention placed two images that differed only by minor degrees of perspective side by side. When viewed through the device’s lenses, the stereoview produced an effect that simulated binocular vision, so that two images shot with a stereoscopic camera would merge into one three-dimensional view.

Though this stereocard is stamped “J. Gurney & Son,” the image was not likely taken by Jeremiah Gurney or his son Benjamin, but rather by V. W. Horton, an assistant at Gurney’s studio. Among the entries in his notebook for the months between February and July 1871, Whitman notes, “V. W. Horton at Gurney’s, cor 5th av. & 16th st.” and, later in the same notebook, enters, “V. M W. Horton photo operator Gurneys.” Years later, Whitman unearthed the original for Horace Traubel. “That picture seems to have been liked,” he told Traubel. “I don’t know but I like it myself. William [Douglas O’Connor] thought it ‘a trifle weak’, but I don’t think so. I can’t always be a roaring lion!”

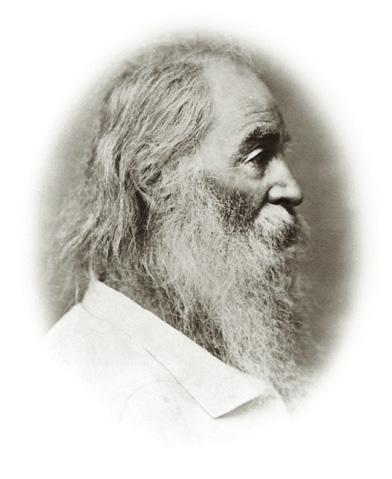

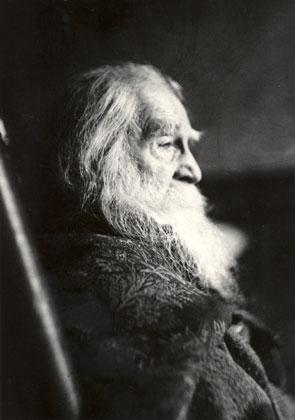

The Spieler Profile

This is one of three photographs taken by Jacob Spieler as studies for Sidney H. Morse’s sculpted bust of Whitman–now on display in the manuscript reading room at the Library of Congress–and the first known portrait of Whitman after his stroke in January 1873 left him with partial paralysis of his left side. On September 7, 1876, Morse paid a week’s rent for an “extemporized studio” at 1223 Chestnut St. in Philadelphia, where he would complete the bust in a few, intense days of work. Morse later wrote: “One part of the preliminary business was the visit to a photographer. [Whitman] knew of one who could be ‘bossed.’ He climbed the flights easily enough, but the heat under the skylight was oppressive. He doffed his coat and sat in his shirt sleeves. A profile of him taken at that sitting shows him looking very old.” The Spieler Studio at 722 Chestnut was owned by Charles H. Spieler, who was long thought to have been the photographer, but the address is entered in Whitman’s daybook with the note “top floor / son Jacob.” A few days later, Jake Spieler is listed among the people to whom Whitman sent a copy of the second printing of the Centennial Edition of Leaves of Grass–in apparent appreciation of his having taken the photographs. This profile remained a favorite of Whitman’s, and he later used it as the frontispiece to the Complete Poems and Prose of Walt Whitman 1855 . . . 1888.

The Butterfly Portrait

Whitman described this image as a “c length with hat outdoor rustic.” Taken by W. Curtis Taylor of Broadbent & Taylor in the spring of 1877, this photograph was recalled by Thomas Donaldson and Elizabeth Keller as being Whitman’s favorite. This infamous portrait, however, led to a great deal of skepticism about Whitman’s honesty, since Whitman sometimes claimed the butterfly was real. “Yes–that was an actual moth,” he told Traubel; “the picture is substantially literal: we were good friends: I had quite the in-and-out of taming, or fraternizing with, some of the insects, animals.” Whitman told the historian William Roscoe Thayer, “I’ve always had the knack of attracting birds and butterflies and other wild critters.” Thayer later wryly commented: “How it happened that a butterfly should have been waiting in the studio on the chance that Walt might drop in to be photographed, or why Walt should be clad in a thick cardigan jacket on any day when butterflies would have been disporting themselves in the fields, I have never been able to explain.”

In fact, the “butterfly” was clearly a photographic prop now in the collections of the Library of Congress. The die-cut cardboard butterfly is imprinted with the lyrics to a John Mason Neale hymn and the word “Easter” in large capital letters. What is not often noted is that the photo simply enacts one of the recurrent visual emblems in the 1860 edition of Leaves: a hand with a butterfly perched on a finger. This symbol is resumed in the 1881 edition. In a review of that edition, published on January 13, 1883, a writer for the Critic referred to Whitman as “the big, good-natured, shrewd and large-souled poet, whose photograph shows him lounging in smoking-jacket and broad felt hat, gazing at his hand, on which a delicate butterfly, with expanded wings, forms a contrast to the thick fingers and heavy ploughman’s wrist.”

The Stafford Portrait

Whitman often stayed with the Stafford family at their farm in New Jersey, where he spent restorative time by Timber Creek, regaining his health after his first stroke. In 1876 Whitman entered into an intense and stormy relationship with young Harry, who often accompanied Whitman to the creek and to whom Whitman gave a ring. The ring was taken back and re-given over the next couple of years, and clearly was thought of as a symbol of deep commitment; Harry wrote to Whitman about wanting the ring back in 1877 “to compleete [sic] our friendship.”

During one of Harry’s visits to Camden in February 1878, Whitman noted: “Feb 11–Monday–Harry here–put r[ing] on his hand again–had picture taken at Morand’s cor Arch & 9th Phil: for Michener, cor Arch & 10th.” The ring is visible on the little finger of Stafford’s right hand. He later wrote Whitman, “You know when you put it on there was but one thing to part it from me and that was death.” Perhaps Whitman chose Augustus Morand’s studio because it was partnered with W. Howard Michener, a painter at 914 Arch Street. Whitman pasted Michener’s card into his daybook sometime in the fall of 1877. Saying that the photo was taken “for Michener” seems to imply that Whitman at least planned to have a painting made from the photo. Perhaps the painting was never undertaken due to his on-again, off-again relationship with Stafford and their long separations. During these years, when they were apart, Whitman wrote Stafford intimate letters: “Dear Harry, not a day or night passes but I think of you… . Dear son, how I wish you could come in now, even if but for an hour & take off your coat, & sit on my lap–”

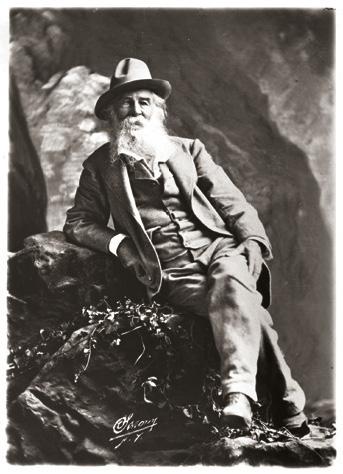

The Sarony Session

At the beginning of July 1878, Whitman was invited by Napoleon Sarony to sit for a group of portraits. Perhaps the first American “celebrity photographer,” Sarony made much of his money selling portraits of famous figures from New York’s burgeoning theater scene–including Sarah Bernhardt, whom Sarony paid $1,500 for the rights to their session. From the mid-1870s to the early 1880s, he also photographed a number of well-known authors, including a famous session with Oscar Wilde during his tour of America in January 1882. But Sarony was famed not only for his celebrity subjects, but also for his amazing (and often bizarre) collection of settings, backdrops, and props. Naturally, Whitman was flattered to be asked and on July 6, 1878, sat for nine photographs. Of all of them, however, this is the most enduring, as it dramatically shows Whitman cast into the world of Sarony’s illusions. As for Whitman, he wrote Harry Stafford on the afternoon after the sitting at “the great photographic establishment” at 37 Union Square only that he “had a real pleasant time.”

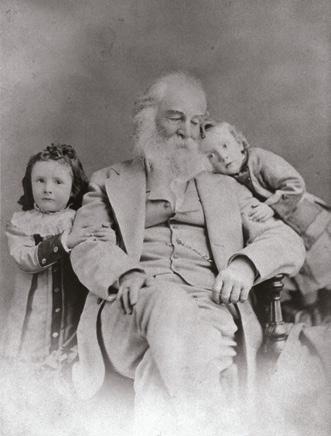

With the Johnston Children

On the back of the Library of Congress copy of this carte de visite by William Kurtz is the inscription: “Walt Whitman with ‘Kitty’ (Katharine Devereux) and ‘Harry’ (Harold Hugh) Johnston, children of John H. and Amelia F. Johnston.” Johnston was a New York jeweler who befriended Whitman and housed him for long stays in New York in the late 1870s. During Whitman’s first stay in 1877, Amelia Johnston died as she gave birth to Harry–and Whitman was protective of the children, especially Harry, ever after, regarding them as “model children lively & free.” Many years later, John H. Johnston remembered that during Whitman’s brief two-day visit on July 6 and 7, 1878, “Walt enjoyed rambling up & down the Avenue and opposite in Central Park with our two youngest children, and one day of his own accord he took them down to Kurtz–then the most famous photographer in New York and had himself photographed with them.”

Whitman may have wanted the photograph because of Harry’s poor health–writing that “I hardly think its tenure of life secure.” Indeed, this shot seems to emphasize the child’s frailty. That same year, Whitman wrote that “The little 15 months old baby, little Harry . . . is a fine, good bright child, not very rugged, but gets along very well–I take him in my arms always after breakfast & go out in front for a short walk–he is very contented & good with me–little Kitty goes too.”

The Pompous Portraits

In 1881, James R. Osgood and Company, a respected Boston publisher, agreed to issue a new edition of Leaves of Grass. On August 19, Whitman arrived in Boston and, over the next two months, oversaw the typesetting of the book at the Rand and Avery printing office. Everything about the book emphasized Whitman’s increasingly conservative stance–and many of the sexual passages were significantly toned down. During this period, Whitman sat for a series of photographs–which he would later dismiss as “pompous”–with photographer Bartlett F. Kenney at 870 Boylston Street. The session may have originally been intended to produce a frontispiece for the new edition, but the book eventually appeared in November without one.

Initial sales of the Osgood edition were strong–and reviews were almost universally positive. Ironically, on March 1, 1882, the District Attorney of Boston declared the book “obscene” and ordered passages to be expurgated or the book would be forbidden from public sale. Whitman initially agreed to consider changes but soon became so frustrated with the long list that he refused. Osgood discontinued the title but handed the stereotype plates over to Whitman–who used them for numerous subsequent printings. The air of respectability forever punctured, Whitman had little use for the Kenney photographs ever again.

The Camden Tintypes

This pair of tintypes, with Bill Duckett, has been dated by early biographer Thomas Donaldson as October 1886 and attributed by Donald Edge to Lorenzo F. Fisler, a Camden photographer at Fisler & Gaubert on Federal Street. Duckett was a friend, driver, and helper for Whitman and traveled with Whitman extensively around this time, escorting Whitman on stage for his Lincoln lecture in New York in 1887, for example. There later were troubles with Duckett, but Whitman recalled in 1889 that “he was often with me: we went to Gloucester together: one trip was to New York: . . . then to Sea Isle City once: I stayed there at the hotel two or three days–so on: we were quite thick then: thick: when I had money it was as freely Bill’s as my own: I paid him well for all he did for me. . . . I liked Bill: he had good points: is bright–very bright.” Duckett sometimes served as driver for Whitman’s phaeton–a gift from his prominent friends, which he received in September 1885 and kept until September 1888.

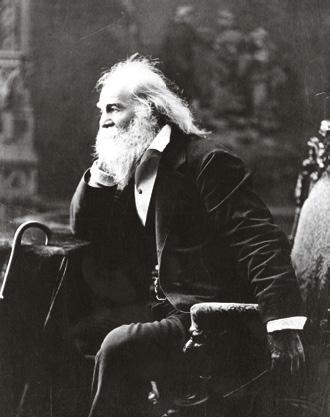

The Laughing Philosopher

On the morning of April 15, 1887, George C. Cox took several photographs of Whitman, who was celebrating the success of his New York lecture on Abraham Lincoln, delivered the day before. Whitman recalled that “six or seven” photos were made during the session, but Whitman’s friend Jeannette Gilder, editor of the Critic, who accompanied Whitman to Cox’s studio, said there were many more than that: “He must have had twenty pictures taken, yet he never posed for a moment. He simply sat in the big revolving chair and swung himself to the right or to the left, as Mr. Cox directed, or took his hat off or put it on again, his expression and attitude remaining so natural that no one would have supposed he was sitting for a photograph.”

This was Whitman’s favorite photograph from the Cox session (“it seems to me so excellent–so to stand out from all the others”), a photo he began referring to as “the Laughing Philosopher.” He asked Horace Traubel: “Do you think the name I have given it justified? do you see the laugh in it? I’m not wholly sure: yet I call it that. I can say honestly that I like it better than any other picture of that set . . . yet I am conscious of something foreign in it–something not just right in that place.” Still, Whitman believed the picture was “like a total–like a whole story,” and he was proud that Tennyson–to whom Whitman sent the photo–admired it: “liked it much–oh! so much.”

The Last Studio Session

Whitman inscribed this photo: “My 71st year arrives: the fifteen past months nearly all illness or half illness–until a tolerable day (Aug: 6 1889) & convoy’d by Mr. B [Geoffrey Buckwalter, Camden teacher and Whitman’s friend, who insisted on the photos] and Ed: W [Ed Wilkins, Whitman’s nurse] I have been carriaged across to Philadelphia (how sunny & fresh & good look’d the river, the people, the vehicles, & Market & Arch streets!) & have sat for this photo: wh—- satisfies me.” Horace Traubel records on the back of a Library of Congress copy of one of these photos that except for the photos taken by Eakins’s assistants in Whitman’s room in 1891, these were the last photos taken of Whitman by a professional photographer–and certainly were the last studio portraits. Whitman thought Frederick Gutekunst was “on top of the heap” as far as photographers went, and considered this photo “a first-rater–one of the best, anyhow.”

Some of Whitman’s friends did not like it as much as Whitman, but Whitman recalled that Dr. Bucke “counts that the best picture yet–says that is the picture which will go down to the future.” John Burroughs also was taken with it: “Gracious! That’s tremendous! He looks Titanic! It’s the very best I have yet seen of him. It shows power, mass, penetration,–everything. I like it too because it shows his head. He will persist in keeping his hat on and hiding the grand dome of his head. The portrait shows his body too. I don’t like the way so many artists belittle their sitters’ bodies.” Whitman liked the rough natural quality of the portrait: “Nowadays photographers have a trick of what they call ‘touching up’ their work–smoothing out the irregularities, wrinkles, and what they consider defects in a person’s face–but, at my special request, that has not been interfered with in any way, and, on the whole, I consider it a good picture.” Jeannette Gilder, writing in the Critic soon after the photo session, described the portrait this way: “From its framework of thin white hair and flowing beard, the face of the venerable bard peers out, not with the vigorous serenity of his prime, but a look rather of inquiry and expectation.” Whitman went so far at one point as to say that “to a person who gets only one picture, this picture is in more ways than any other spiritually satisfactory and physically representative.”

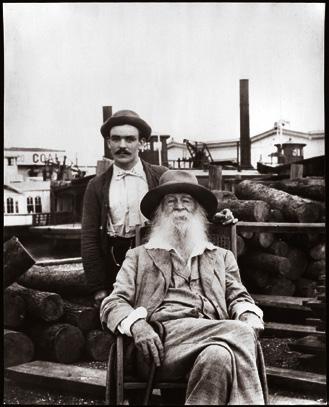

On Camden Wharf

Taken on Camden wharf in 1890 by Dr. John Johnston of Bolton, England, this photograph shows Whitman in his wheelchair, attended by his last and favorite nurse, Warren Fritzinger. “Warry,” Whitman said, “is faithful, true, and loyal.” Whitman called him his “sailor boy,” and he indeed had spent years at sea. He was the son of a friend of Mary Davis, Whitman’s housekeeper; when Warry’s parents died, Mary became his guardian, and she talked him into becoming Whitman’s nurse. He was a comfort to Whitman in the last years: “I like to look at him–he is health to look at: young, strong, lithe.” Dr. Johnston, one of Whitman’s English admirers and a founder of the “Eagle Street College,” arrived in Philadelphia to visit Whitman on July 15, 1890, and that evening photographed Whitman and Fritzinger, who were out for a walk, Fritzinger pushing Whitman in his wheelchair (which had replaced his phaeton as a mode of transportation in 1889): “As we approached the wharf he exclaimed: ‘How delicious the air is!’ On the wharf he allowed me to photograph himself and Warry (it was almost dusk and the light unfavourable), after which I sat down on a log of wood beside him, and he talked in the most free and friendly manner for a full hour, facing the golden sunset, in the cool evening breeze, with the summer lightning playing around us, and the ferry-boats crossing and re-crossing the Delaware.”

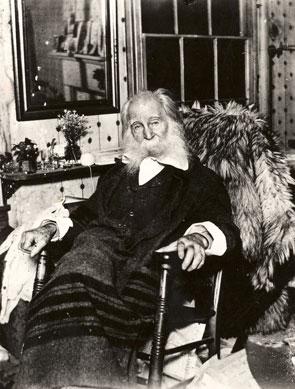

Reeder Flash Photographs

Dr. William Reeder was a Philadelphia physician and admirer of Whitman. On May 24, 1891, Horace Traubel recorded Reeder’s visit the previous night, when he took “flash pictures in front & back bedrooms.” In the smaller, more faded of the surviving photographs, the legendary chaos that surrounded Whitman in his last years is visible in the confusion of manuscripts and crumpled newspapers piled under and around his rocking chair. Whitman likened the mass of paper to a sea and resisted efforts of his housekeeper and friends to sort it out. Something in the disorder of his papers seemed almost to mirror Whitman’s aesthetic of pastiche and all-inclusiveness. Whenever pressed, he always insisted that whatever he needed surfaced eventually.The

The Last Photographs

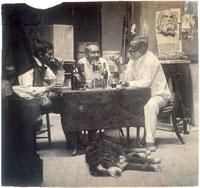

In May 1891, Samuel Murray, a student of Whitman’s photographer friend Thomas Eakins, and the New York sculptor William O’Donovan visited Whitman’s home. Murray took photographs of Whitman as an aid to O’Donovan’s sculpting the poet. “They took hell’s times in all sorts of posishes,” Whitman groused, but the photographs proved indispensable. In a group portrait of (L to R) Murray, Eakins, and O’Donovan (along with Eakins’s dog, Harry) taken at Eakins’s studio on Chestnut Street in Philadelphia, the nearly completed bust of Whitman can be seen over O’Donovan’s shoulder. Tacked to the wall next to the bust is one of Jacob Spieler’s portraits of Whitman, one unidentified close-up portrait, and at least four smaller prints from Murray’s session. Though Murray’s photographs were intended merely as studies, they are especially important because they are the last photographs taken of Whitman before his death in March 1892.