Daniel Heyman chose Dartmouth instead of art school. A mistake? Not for Heyman. He spent a year abroad in France, hosted by an older woman, listening to her stories about surviving World War II. After graduation, he went back to collect memories from people in Normandy, the Loire Valley, Paris, seeking those who had lived through war, Jews who had been hidden as children, people who helped others escape. He began to paint their stories but stopped, frustrated by his own lack of skill. He enrolled in graduate school at the University of Pennsylvania where third generation Modernists urged him to remove all narrative from his work. Not willing, but not yet finding his own way technically, he abandoned his pursuit of violence and became successful as a painter of gay life.

Still, human violence continued to creep into his work. He was drawn, in particular, to the true account of young Eddie Polac, brutally beaten to death in Fox Chase, near Heyman’s home in Philadelphia. He painted such records of violence, not unsuccessfully, but always from other art or newspaper accounts. Painting, however, exists in stillness while violence, rifts from meaning, ripples, falls back upon itself, generates more violence. The artist, sensing this, went to Japan to study woodblock printing. His paintings began to look like prints.

A friend invited Heyman to dinner to meet someone else haunted by human violence, Susan Burke. A human rights attorney, she had been hearing reports about “the gloves coming off.” In 2002, she had read a statement by an unidentified government official who said, “If you don’t violate someone’s human rights some of the time, you probably aren’t doing your job.” Incensed, she found a like-minded attorney, Jonathan Pyle, and they set up their own firm, Burke Pyle Ltd. That same year, 2003, Heyman remembers, it was rumored that “the employees of a pair of corporate military contractors allegedly conspired with government officials and military personnel to rape, pistol-whip, threaten, electrically shock, molest, verbally assault, kick, sodomize, urinate on, and otherwise torture Iraqi nationals both in Abu Ghraib and other locations across Iraq.”

By the time Heyman and Burke met, she and her team of Philadelphia attorneys were representing a group of Iraqis in a massive class-action lawsuit that would be filed in the United States District Court of Washington, DC. Halfway through that life-changing dinner, Burke invited Heyman to join her on a fact-finding trip. Instinctively, she knew that artists could command immediate public attention, where the slow legal process can take years and rarely attracts much press—but she needed the right kind of artist, an artist who had honed his techniques, an artist whose heart had been schooled to bear witness.

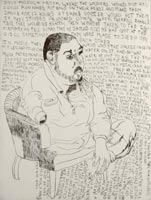

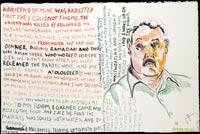

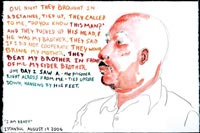

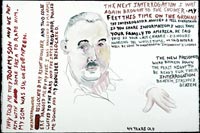

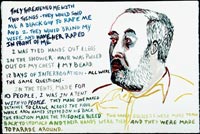

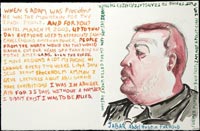

In March 2006, Heyman traveled to Amman, Jordan, and five months later to Istanbul. Now, instead of making art derived from secondary sources, he was to actively collect evidence through his art. He wondered if it was possible to make violence real in a world where mass media has desensitized the audience, where violence has become entertainment. And these Iraqis were civilians, were guilty of nothing (none was ever charged)—could he convey their innocence, as well as tell their terrible stories? For eight days he sat in on interviews with victims of horrendous abuse, recording the testimonies of former Iraqi prisoners tortured at Abu Ghraib. The eight copper plates he took with him were used up in three days, and Heyman switched to watercolor.

Working quickly, he sketched portraits of humble men and occasionally women, all dressed in modest, civilian clothes. But it was the words coming to him through a translator that haunted him. Words—tumbling, flooding words—engulfed the artist and soon the portraits themselves, as he inscribed into each work the detainee’s own telling of their imprisonment and mistreatment. He had found his means: prints, the commoner’s version of painting, and watercolors, the medium oft-claimed by amateurs, all overrun by words.

“I went to Jordan and Turkey convinced that artists have a role to play in the great issues of their times,” Heyman remembers now. “My goal is to reclaim for the victims of torture their right to describe what happened in their own words. My purpose now is to find public institutions that will either exhibit or acquire these works, in an attempt to keep them alive and the testimony they contain as available for public study as possible.”

Daniel Heyman’s visual stories echo that ancient refrain uttered by artists throughout time, “If I live, I will tell. If I don’t live, my art will tell.”

—Laurel Reuter