The term “burned earth” finds its roots in an ancient military strategy of destroying your enemy’s crops by setting them ablaze, of torching their homes and food stores, defeating them not by direct warfare but by an ever tightening stranglehold—starving them out, breaking their will. In recent years in Egypt, the age-old term was repurposed to describe the unfair—and often random—arrest and mistreatment of citizens by the military in an effort to instill fear in the populace.

The technique was central to the Emergency Law Campaign, enacted during the rule of recently ousted president, Hosni Mubarak. When President Anwar Sadat was assassinated in 1981 by members of his own military, who opposed his signing of the Israeli Peace Accord, Vice President Hosni Mubarak was sworn into power. He immediately invoked a State of Emergency— one that was never lifted during his thirty-year rule. Habib el-Adly, Mubarak’s Minister of the Interior beginning in 1997, masterminded the extension of the Emergency Law to include regular use of kidnappings, prolonged detainment without trial, rapes, torture, and execution, with the justification that such techniques produced intelligence about state enemies.

When I was in Cairo documenting the Arab Spring—and Mubarak’s generation-long grip on the Egyptian people was finally loosening—I began to hear long-suppressed stories from people who for years had kept silent: mothers whose sons had been arrested and never come home, men who suffered extreme pressure from authorities to become informants, children imprisoned as hostages for their wanted fathers, and subjects of extraordinary rendition, sent to Egypt from American anti-terror facilities worldwide, so they could be tortured legally. Most of the people I interviewed told me they were arrested after a friend or neighbor had given their name to authorities under the duress of Burned Earth techniques. They explained this, often, without anger, because when they were forced to endure the dousings of icy water and the electroshocks, they too gave names—any names. And so the cycle continued.

As Egypt emerges into its new political and social present, I wonder what the Egyptian people will do. Will the military be able to reform? Will a new government resist the temptation to hold on to power by extending Mubarak’s laws? And what will the American government do? We have an unquestionable stake in stabilizing this strategic nation. But will we choose to support true democracy, regardless of where it leads? Or, as we did with Mubarak, will we endorse and support a government that favors our interests and protects our secrets?

For the moment, the streets of Cairo are buzzing with the notion that, after so many years of fear, the people can fight back and win. But there are many battles remaining before the Burned Earth era has truly ended.

Gamal

Gamal was the son of a poor farmer in Upper Egypt, where rich soil flanks the southern stretches of the Nile. On June 28, 1992, as on most mornings, he rode his donkey toward his farm. For some unknown reason, police opened fire on the boy and his donkey. Eighteen bullets tore into Gamal’s thirteen-year-old body. Fifteen struck his abdomen, and the final three struck his back as he tried to run away.

Gamal’s body lay on a metal tray in the morgue. Had it not been for a doctor who noticed the slight rise and fall of his chest, he would have been left for dead. In the months that followed, Gamal’s father received threats from State Security urging him to keep quiet. Not that he had any evidence, other than his son’s bullet-pocked body. Someone had altered Gamal’s medical records, and the official police reports reflected no wrongdoing.

Gamal was paralyzed for two years, and the operating room become his second home.

The government did not cover any of Gamal’s medical expenses.

Sayana

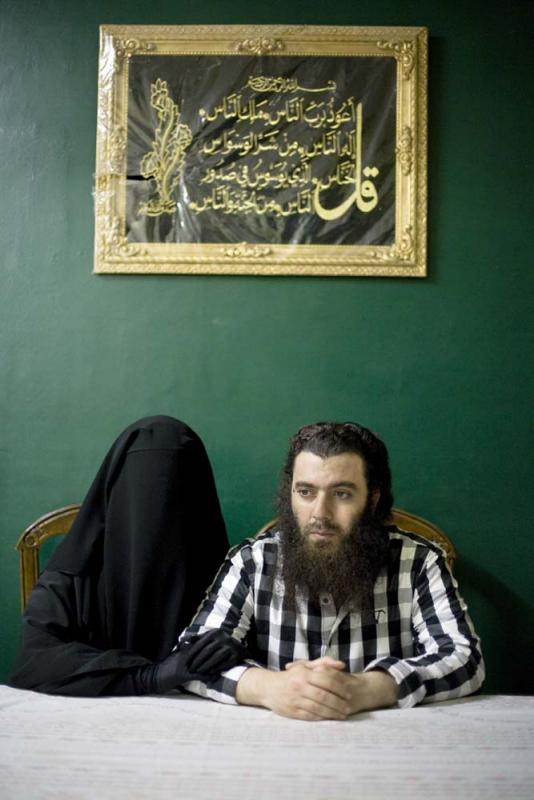

Two plates of fried fish lay on the oversized dinner table in Sayana’s and Ahmad’s new home in Cairo, a home in which Sayana still felt like a stranger. She dabbed tears with her black polyester nijab, careful to preserve her mascara.

Sayana was no stranger to tears. She’d fled the war in Chechnya at the age of thirteen and had been married once before, to a Muslim man from Dagestan who fled Russia to avoid persecution by the secret police.

She and Ahmad had fallen in love over long-distance web chats in broken English. They eventually found themselves strolling arm-in-arm along the nile as husband and wife, but just two months after they were married, state security arrested and tortured them both.

Sayana was deported to Russia, where she worked to no avail to have Ahmad freed through human rights organizations. Three years dragged by. Desperate, she hired a human trafficker to transport her to Sweden, where she hoped to reach relatives. She made it all the way to Germany before border officials detained her for traveling under a counterfeit visa. In a stroke of luck, the Germans granted her asylum.

The protests in Tahrir square sparked a flame of and made it possible for Sayana to return to Cairo. But Sayana doesn’t have legal residency in Egypt, and with so much disarray in the government, it may be years before she can rest assured that another deportation isn’t yet to come.

Amr Adel Ibrahim

By January 29, 2011, the day angry crowds of Egyptian protesters burned police stations across the country, twenty-nine-year-old Amr, had been locked behind the cement walls of Cairo’s Abu Za’bel prison for a year. He’d grown accustomed to regular beatings, but not to the way he felt when the guards sang the Egyptian national soccer team’s victory song as they stripped him naked to attach wires to his scrotum, fingers, toes, and earlobes. Pain was pain, but it was the humiliation that got to Amr. He gave them names, any names that came to mind. Sometimes, names made them stop.

When the guards opened Amr’s cell on January 29, they weren’t singing any songs. They’d come to set him free along with the rest of the inmates of Abu Za’bel, criminals and political prisoners alike. Thousands of prisoners were released that day to sow panic in Cairo, one among several of President Mubarak’s last-ditch attempts to frighten protesters off the streets.

Amr was freed without ever knowing why he was jailed, much less why he was tortured.

Mohammad and Abdel Rahman

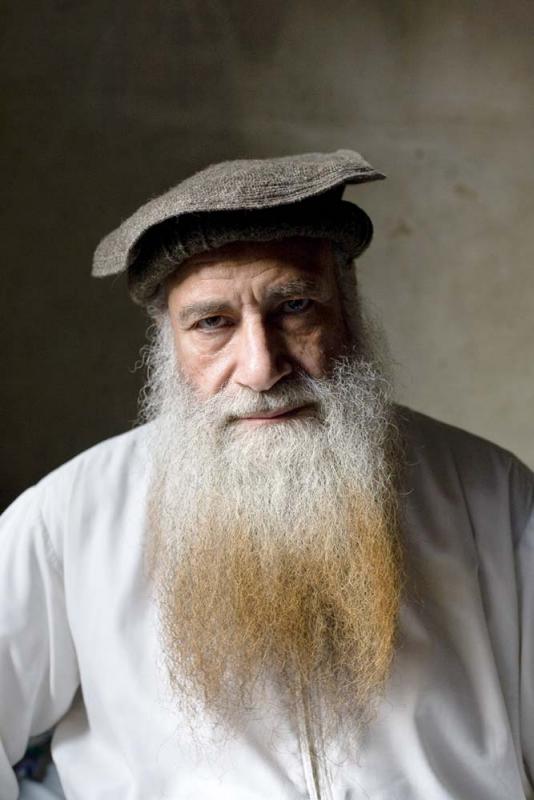

In the 1990s, Mohammad moved his family to Lahore, Pakistan, where he took a second wife, started an electrical engineering business, and was eventually arrested on suspicion of ties to Arab jihadis living in Pakistan. Abdel Rahman, Mohammad’s oldest son, was fourteen when his father went to prison. Pakistani authorities extradited Mohammad to Egypt, where he would spend the next seventeen years confined to a cell three meters square.

Abdel Rahman found himself the man of the house. Still in Pakistan, he had to provide for six siblings and two mothers and keep Mohammad’s engineering business afloat. in 2001, America’s war against the Taliban in Afghanistan made life still harder for Arab families in Pakistan. Then, in 2004, Abdel Rahman was kidnapped from a bus station, blindfolded, and severely tortured by Pakistani police. Americans also questioned him. They threatened to send his entire family to Guantanamo if he didn’t turn over his “cell.”

For four months, Abdel Rahman’s family heard nothing of him. Abdel Rahman didn’t know where he was either, until suddenly he was being handed over to Egyptian authorities. He heard the drone of jet engines and guessed what was coming.

“When I entered the plane I prayed that it would crash because of what I knew from my father about his treatment in Egyptian prisons,” Abdel Rahman told me. In Cairo, state security tortured Abdel Rahman mercilessly. He was eventually released for medical reasons, only to be imprisoned again in 2008 after speaking out to human rights organizations about his father’s detention.

Neither father nor son have ever been charged with a crime.

“When I think about what happened to me, I am not so much upset about the torture, I’m most sad about all the time that has passed,” Mohammad said.

“They stole years of my life from me. I don’t even know my children anymore.”

Mohammad Attiah

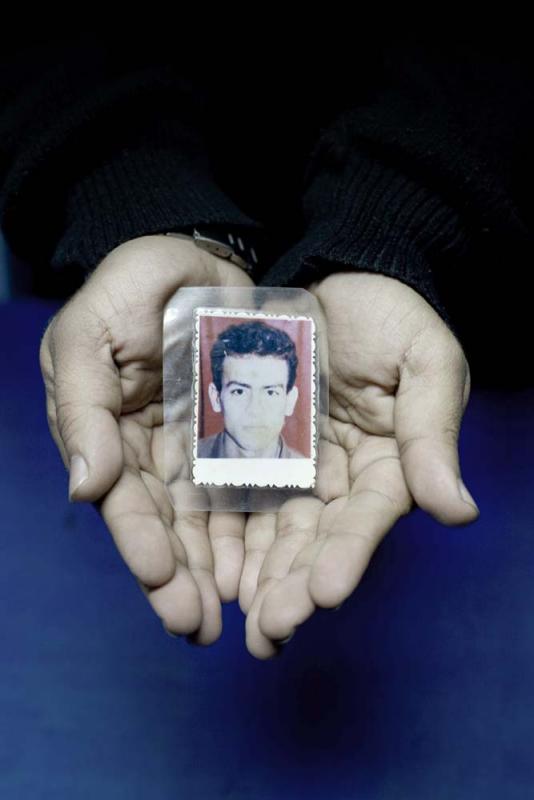

Helwan seemed like the end of the earth—the last stop on the metro out of Cairo, and another twenty minutes by taxi to reach the slum where Mohammad Attiah disappeared. It was eighteen years ago, and it broke his mother’s heart for good.

I stepped up to the nondescript doorstep of Mohammad’s childhood home, where his brother, Sohaib, led me to their mother, Noel Zaki Abdel El Hamin, who was bedridden with grief and kidney disease. “Mohammad, Mohammad, Mohammad,” she murmured, her son’s name slipping out just under her breath as tears began to wet her cheeks.

For nearly two decades—ever since the police snatched Mohammad from the mosque across the street—Noel has whispered his name continually. A verbal tic, a prayer. She told me that if she stopped saying his name, it would mean that she had given up hope, that she had stopped waiting for him to walk through the door.

The government told Mohammad’s family nothing. His family searched for him in Cairo’s prisons during all the years of he’d been gone, but he had vanished without a trace.

Mohammad Yousuf

“When I was in prison, I wouldn’t let them break me,” Mohammad Yousuf told me in a perfect American accent. “But when I got out,” he continued, “I was broken.”

We were sitting in his apartment in Nasr City, a threadbare Cairo suburb that retains its solidly middle-class character. Mohammad unspooled his bizarre history. In 2004, US Attorney General John Ashcroft placed Mohammad on America’s a list of the five hundred most wanted terrorists. That same year, Ashcroft named Mohammad a suspect in Rumsfeld v. Padilla. As Mohammad told me these things, I had the feeling I was before a minor celebrity.

Mohammad had immigrated to New York in the 1980s to work as a gate agent for American Airlines. He later moved to Miami, where he worked at a car dealership and eventually became an American citizen. It was when he got involved with Dade County’s Muslim community that he began to suspect the US government was watching him. The Ft. Lauderdale mosque where Mohammad became a board member happened to be the same one Jose Padilla frequented after his release from prison.

In 1996, financial difficulties compelled Mohammad to move back to Egypt. Five years later, 9/11 happened, and a few years after that, policemen with machine guns showed up at Mohammad’s door.

“Did you know we were coming?” the police had asked him.

“Yes,” he’d told them.

In post-9/11 Egypt, Mohammad told me, an Islamic-style beard and a history with airline companies were all you needed to get locked up. In prison, he was severely tortured, and his torturers used means beyond the prison walls. They tried to coerce his wife into divorcing him, shaming her and depriving his children of a father, which also meant depriving a family of a livelihood.

In 2009, Mohammad got out of prison and returned to his wife, but he still fears reprisals from the American government.

Zeinab

Zeinab was due in a week or two, but it was hard to tell how pregnant she was under her nijab. She suffered from epilepsy, and her condition had worsened under the stress of her husband Akram’s incarceration. She worried her epilepsy and heightened stress might cause health problems for her baby.

Akram was imprisoned in 1988 at the age of seventeen for taking part in a movement on behalf of Islamist prisoners. He has been in and out of prison ever since.

In 2005, after suicide bombers killed three foreigners near Cairo’s Al Azhar Mosque, Akram was re-arrested and tortured with so much electricity that Zeinab said she could feel a buzz in his body when she touched him.

As she told the story of her husband, Zeinab looked pensively at his photo, then held it up to her swollen belly as if to introduce her unborn baby to its father. The air was heavy with melancholy, but it was a humorous gesture. We all laughed.