While visiting the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum, a former Khmer Rouge prison camp in Cambodia’s capital city of Phnom Penh, Binh Danh studied closely the mug shots of former prisoners. Danh, a Vietnamese-born artist whose family fled to a refugee camp in Malaysia in 1979 and eventually emigrated to the US, was haunted by the faces of the dead. “Each has a different story,” he remembers now, “but all ask the same question: How could this happen?”

During the years of Pol Pot’s rule, one of the most lethal of the twentieth century, an estimated 1.7 million people died as a result of mass execution, torture, overwork in labor camps, and starvation. Those suspected of being “national enemies”—foreigners, professionals, artists, teachers, Christians, Muslims, Buddhist monks, homosexuals—were rounded up and systematically put to death by the Cambodian government in prisons such as Tuol Sleng.

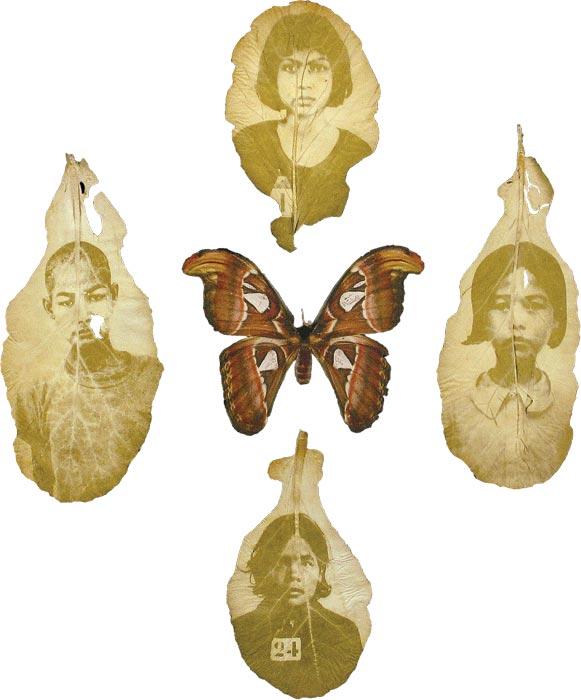

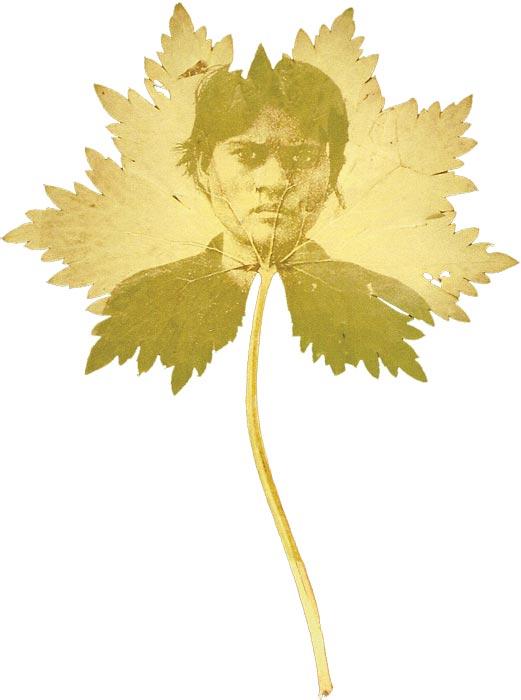

Danh knew the numbers, but it was seeing those faces that pushed him to seek out a medium to visually record human memory, to emphasize the fleeting nature of mortal existence. He eventually devised his “chlorophyll prints,” in which Danh places photographic negatives of portraits from the Tuol Sleng archives onto living leaves, creating ghostly images of the victims from the shadows their faces cast. According to Danh:

I have tried to show how like plants humans are; we participate in the kinetics of events and the process of creating memories by absorbing the history around us—and, like leaves, we wither and eventually die. The residue of our existence nourishes the memories of the living like a decaying leaf nourishes the soil.

The eloquence of this union of forms—material and ephemeral—moved poet Robert Schultz, when he saw Danh’s work at the Art Museum of Western Virginia. He was struck by “the uncanny connection between Danh’s art and Walt Whitman’s central trope—the leaves of common grass seen as hieroglyphic,” and he became “determined to render Danh’s pictures back into words.”

One night, Schultz awoke with the solution he had been seeking—the formal structures and urgent refrains of repeating poetic forms: pantoums, villanelles, triolets. “It was not until I understood that my leaves were the poetic forms, with their own cyclings and repetitions that I could finally write these poems,” Schultz reflects. “The subject matter demanded restraint, the slight distancing of given forms. But the forms themselves had to enact the organic cycles that Binh Danh’s chlorophyll prints insisted upon.”

In “Khmer Rouge,” for example, Schultz uses the strictures of the pantoum—repeating the second and fourth lines of each quatrain as the first and third lines of the following quatrain; repeating the first and third lines of the poem as the third to last and last lines—to introduce and interrogate the regime’s empty sloganeering. Schultz underscores not only the over-simplifying of the Khmer Rouge’s bureaucratic logic but also the relentless repetition of the executions themselves.

Taken together, Danh’s images and Schultz’s poems form a narrative of the dark hells of the Cambodian genocide, and—like Orpheus returned from Hades—they carry with them the dead reborn. “As the stories tell, / To rise we go down,” Schultz writes in “Found Portrait #18”; these stories for Danh and Schultz “begin in the underground,” where the thousands upon thousands of Cambodian bodies lie. Yet, in the common dirt, their stories take root. Through Binh Danh’s art, they evolve into natural and historical reincarnations of past tragedy, physical reimaginings of lost memory. As Schultz writes in “Ancestral Altar #7”: “The dirt took them / into its dark / and sent them back / in caladium leaves / … and here they are— / the bitten faces / fleshed in green.”

Khmer Rouge

If you wore glasses, if you drank milk—

Showed signs of learning or foreign habits—

You were impure. They said of thousands,

“Spare them, no profit; remove them, no loss.”

Show signs of learning or foreign habits

And they sent you out to dig canals.

“Spare them, no profit; remove them, no loss”—

The motto emptied cities. In “year zero”

They sent thousands out to dig canals,

Directing floods for the great harvest.

In year zero a motto emptied cities,

Filled Tuol Sleng and the killing fields.

They directed floods in a great harvest;

They said to thousands, “You are impure.”

You were sent to prison or the killing fields

If you wore glasses, if you drank milk.

Ancestral Altar #7

The soon-to-be-dead

were photographed, filed—

two boys, a girl, with tags

on their shirts, numbers

of the photographed filed

in metal drawers,

numbered by the tags on shirts

to be kept in order,

kept in drawers

by men who killed

for a kind of order,

for purity and clear ideas.

The men who killed—

two million gone

for purity and clear ideas—

trenched mass graves

where two million

sank into earth,

into shallow trenches, graves

of mingled bones.

They sank into earth

and the dirt took them,

mingled their bones

and sent them back.

The dirt took them

into its dark

and sent them back

in caladium leaves

that rose from dark

and reached for sunlight,

caladium leaves

whose bitten faces

reached for sunlight,

and here they are—

the bitten faces

fleshed in green.

And here they are,

two boys, a girl, with tags,

newly fleshed in green,

the soon-to-be-dead.

Found Portrait #5

The portrait is changed

By art and belief

To something strange—

A man and butterfly in a leaf.

In this dire moment

Is he terrified or serene,

Standing, arrested, in his green

Flame, shroud of living fire?

The leaf’s central vein

Rises like a seam

He could open at the stem

To escape from pain

Or to free the butterfly

Clinging to his shirt.

There it sits, chest-sized, inverted,

Lung-shaped, spotted,

Ephemeral as the sigh

That escapes his lips

As the shutter clicks

And will not die.

Found Portrait #18

In hell’s dim halls

My vision clears

And a face appears,

But a face that appalls.

Leached of color,

She glares from a leaf—

Her corona of grief

Like the fancy collar

On a birthday coat—

But its stem and spreading

Veins reach like a spider clinging

To her throat.

As the stories tell,

To rise we go down;

The trip begins underground

In one of many hells.

We go down to rise,

Changed in each other’s eyes

By suffering recognized

As monstrous, human-sized.

The Chankiri Tree

At the killing field, Choeung Ek, no bells are rung.

In a tall stupa, piled skulls cannot blame or resent

This staring crowd—emptied bones without tongues.

Pathways lead between excavations begun

And abandoned. The plain is scarred with shallow dents

Bordered by trees where children climb the rungs.

In a low building, victims’ photos, hung

In rows of black and white, draw the murdered present.

I scan across the peering eyes, struck dumb.

Back outside in the glaring sun, leaves are stung

With images—faces risen, called up and sent

To green the tree of knowledge rung by rung.

See, they return: In the wide ditch new grass has sprung

Where bones still lie, shaded by the tree’s broad tent.

When a breeze moves, leaves whisper what they’ve become.

The bark is torn. Against this trunk executioners flung

The bodies of children. Bullets, costly, were rarely spent.

We climb the tree of knowledge rung by rung.

O I perceive after all so many uttering tongues.