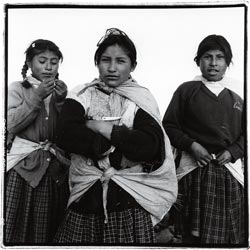

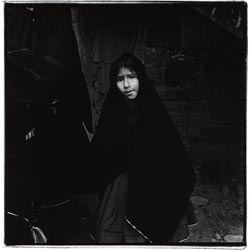

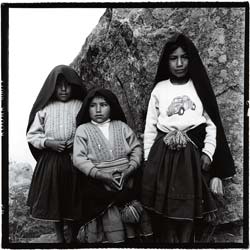

In the dwindling light, three girls clamber over the rocks of the Pachamama temple, carrying loads of sticks for their family’s cooking fire. Below them, a huge expanse of water stretches toward the lights of Puno, Peru, on one horizon and away to the snow-peaked mountains of Bolivia on the other. The girls scramble down the hillside to their homes, the only sound their soft footsteps rustling through the grass.

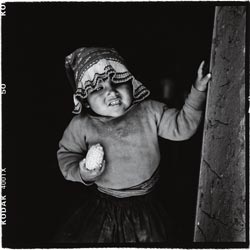

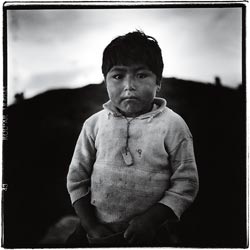

The two islands in Lake Titicaca—Amantani and Taquile—are home to two communities of subsistence farmers. These islands were once part of the Inca Empire; the islanders still use the Quechua language and live, more or less, as they always have. They grow corn, potatoes, broad beans, and quinoa, and most families will keep a few sheep. But occasionally, for a special event, they celebrate by feasting on a lamb or stewing a type of weed from the lake with milk.

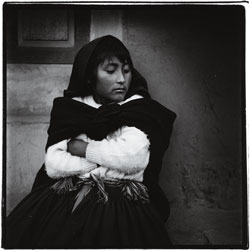

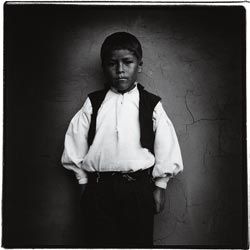

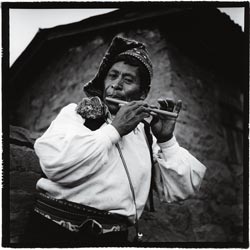

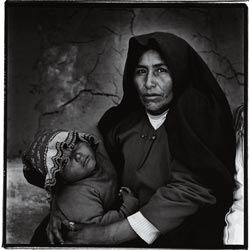

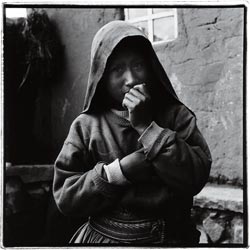

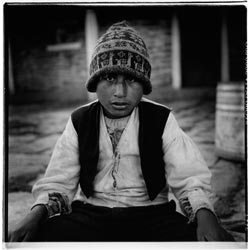

On my first trip here in 2000, I visited the home of Francisco Quispe—a typical Taquileño in a traditional white shirt and black vest. In his smoky kitchen, I could barely breathe, let alone make out the vague shape of Francisco’s wife fanning the fire. Their three children sat expectantly around the table, their faces lit by the glowing embers. This was a rare break for them; they were usually busy with the endless daily chores—collecting wood, tending to the land and cooking. The quiet moments in between were spent spinning wool or weaving. When I ducked out of the room for some fresh, Andean air, I could just make out the crackle of a battery-powered radio wavering across the hills. Was it the notes of an old Peruvian bolero, or the lost words of some Bolivian folk singer?

Tourists from all over arrive here daily with modern clothes, cameras, and crisply folded bills. By the islanders’ own count, an average of forty to fifty thousand outsiders visit annually, descending on a tiny local population of about two thousand. Most of the revenue from this lucrative influx is siphoned off by the local Peruvian tour operators, but active local community members like Francisco are trying to regain control of the tourist industry. They are looking for ways to manage tourism in less exploitive and more sustainable ways, and trying to keep more of the economic boon for the island population. Most importantly, they have set up collectively owned and operated restaurants, artisan shops, and visitors’ accommodations. Francisco often volunteers to look after the two artisan shops in the main plaza, a task that is rotated weekly among families that are able to spare someone. The profits are shared.

Though they recognize their reliance on the tourist trade, the islanders remain proud of their ability to distance themselves from the modern world. Water pumps, electricity, and proper sanitation are starting to make their way here, thanks to Western donors, but the islanders stubbornly resist change. As the local expression goes haniwa—stubborn resistance.

Over the years, Francisco has always asked me to bring him wool when I visit the village. The brightest colors are his favorites. I bring sacks of wool, rice, sugar, salt, and cooking oil. Struggling with my load up the stone steps from the port to the village above, I find it hard to imagine that one day satellite dishes might blossom from every rooftop. For now, there are no computers here. The nearest television is a two- to three-hour boat trip away on the mainland. Most modernity remains literally over the horizon.

Globalization encroaches on all territories, and inevitably it will wash up on the shores of these isolated islands too. With it will come many benefits and many losses. Stoves and smoky kitchens will be improved, along with education and healthcare. But the t-shirts that have already arrived will soon be followed by modern vices—trash, alcohol, obesity. For now, however, it seems nothing could threaten the ancient sky above the mountains, the confusion of stars reflected in the silent lake.

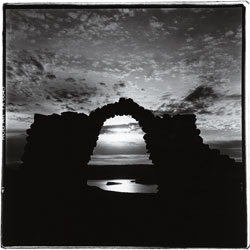

Here on Lake Titicaca—before the arrival of the tourists, before the appearance of the local sailing boats with their strange, inverted sails—they say the original Inca rose from the waters. Manco Capac, according to legend, stepped out of the lake to establish the city of Cusco and the now lost empire of the Andes. Despite centuries of war, colonization, and trade, his people remain here on Amantani and Taquile, and his story somehow floats, immortal, above the water.