1. A Short Chronicle of a Long Childhood

It is an unusually warm morning in San Francisco. My parents are sitting on the back porch reading the paper, sipping coffee. Suddenly, there is the sound of broken glass as I come flying through the window behind them. A surreal moment—it’s difficult to tell who is more stunned, my parents or I.

While nearly the entire window is gone, I have only minor cuts. The one who will suffer as a result of this outburst is my younger brother, Rory, who pushed me.

Rory and I love each other, but like most brothers, we fight, both verbally and physically. I can whip him pretty easily, but I lack his explosive temperament. I enjoy a good fight; my friend Billy and I go at it from time to time and are evenly matched. With Rory I often walk away before it comes to blows. Sometimes, he chases after me.

A couple of years later, in a different house, chasing me again, enraged about something, Rory puts his hand through a glass-paneled door. He fares worse with the door than I fared with the window. There is blood—lots of it—and a visit to the emergency room and many stitches, which leave a permanent scar on his right palm.

Rory screams. Rory yells when he doesn’t get his way. Rory roars. It’s as if he were born angry.

From early on, Rory was odd, sensitive, and shy. His birth was difficult, whereas mine was easy. He was born with a turned left eye and as a toddler had to wear glasses and an eyepatch. (There is a photograph of Rory, aged two, sitting on a swing wearing his glasses and eyepatch, and screaming.) The treatment doesn’t work, and over time Rory ends up losing most of the sight in that eye. His main disappointment is that he can’t fully appreciate 3-D films. In a strange twist, when our father is in his midforties, he will lose the vision in his right eye, the result of a botched cataract operation.

Rory continues to wear glasses until he is eight or nine. He hates not being able to see clearly—the glare off the lenses throws him into paroxysms of frustration.

Rory is eighteen months younger than I—as withdrawn as I am outgoing. I star in school plays. Rory gets sent home with teachers’ notes. I have been blessed with the ability to make friends, but Rory is the only friend I keep for long. Our family moves constantly. By the time I am twelve and Rory ten, we have moved ten times. We can never discern a reason; our parents are simply restless, dissatisfied, hoping the new home will improve their lives. But no matter where we live, they create a safe, warm environment. I am happy. My mother draws pictures and cuts paper dolls for us. One night, while I sleep, she sews me a hand puppet, which I discover on my pillow in the morning. She makes Rory a sock doll that he names Lady Viniver.

From early on, Rory and I draw. We draw for each other. We collaborate on wordless picture-stories before we are able to write. Our heroine, Little Miss Lady, stars in a series of adventures wherein she is set upon by villains or the Devil himself and must survive one peril after another.

Rory doesn’t share my fascination with fairy tales and Disney animation, but in everything else our interests coincide. We both love comic books (Little Lulu, Uncle Scrooge, Sugar and Spike), horror and fantasy films, robots, giant monsters, glider planes, amusement parks, and fanzines.

Our work reflects this. When we begin to write as well as draw (I am nine, Rory seven), our first hero is one of our stuffed dolls, a teddy bear: Patrick Pooh, named after Patrick Henry (the name of our grade school) and Milne’s character. At first a Dennis the Menace type, he mellows over time and becomes a child adventurer, vampire-slayer, superhero, hard-boiled detective, or mad scientist.

Mom, always very much a child herself, likes the same things we like, especially the same kinds of movies. Dad works the night shift at an upscale Italian restaurant and sleeps most of the day, so we see little of him, making him ever more of a stranger. Most of our time we spend with Mom. She plays the part of grownup admirably: in charge, stern when she needs to be, protective, helpful, and responsible. She maintains this facade until Rory and I are nearly adults.

It is the only summer that we live outside San Francisco, in nearby Brisbane. Rory is sitting under the tree in our front yard. He has been there for nearly an hour, lost in his own world. Occasionally, he emits spontaneous sounds that are not quite words. In the same year and the same house, Rory will put his hand through the paneled glass door. Mom and Dad have recently taken him to see a psychiatrist because his behavior has grown bizarre. Every time a car passes the house, he makes a small grunting noise and taps the ground twice—a strange, protective ritual.

In the 1950s doctors have limited knowledge of personality disorders, and there are no safe medications to alleviate mood swings. The psychiatrist puts Rory through a series of cognitive tests, asks questions, determines there is nothing to be concerned about, and sends him home. Or that’s the story I get. In any event, my parents decide not to pursue things, hoping that what we all (Rory included) refer to as his “nutty habits” are just a phase he will outgrow—which, in a couple of years, he does.

When I begin junior high, Rory and I are in different schools, and this makes him anxious. He is awkward, never a teacher’s favorite (they don’t have patience with him), and his shyness is an invitation for other kids to pick on him. A horror movie we saw at the drive-in has upset him, despite his love of horror films. It is The Blob, starring Steve McQueen. Rory is terrified that the blob has somehow entered his bedroom and is hanging on the ceiling directly above him.

I like living in Brisbane. Rory doesn’t. It makes no difference; after a single year, we are back in the city.

Puberty, far from separating us, brings us closer together. I am miserable in junior high. For three years, Rory is my only friend, my willing sidekick in our extended childhood. As a defense against the onset of sex and adult responsibility, Rory and I fortify our creative world. We still own almost all our old stuffed toys. By now they have distinct personalities and are stock performers in our stories and plays. We know our peers aren’t playing with dolls, but this is our secret. It is, we feel, necessary.

We produce posters for our imaginary films (we won’t have an 8mm camera for several years yet), fanzines to discuss them in, and comic books. One of my earliest stories is about a prehistoric monster that comes to life and terrorizes a city; another is a pirate epic, The Treasure of Lagoon Island.

Both huge fans of Chester Gould’s Dick Tracy, we create our own versions of the character: mine is a human detective named Frank Poole, and Rory’s a teddy bear called Dick Pooh. Rory is more prolific, creating a series of Dick Pooh adventures. I eventually abandon Frank Poole and write some Dick Pooh stories of my own.

Our literary tastes are quirky. Young adult novels don’t exist yet, so at thirteen or fourteen we plunge into adult books. I’ve passed my Mark Twain–Robert Louis Stevenson phase and read To Kill a Mockingbird. Rory, not surprisingly, loves M. R. James, Poe, and a book called The Victorian Chaise-longue, by Marghanita Laski. For about six months we focus on Shakespeare. Our parents own a limited-edition First Folio, beautifully illustrated, each play in a separate volume. We spend hours reading the plays into a tape recorder, sharing out the parts. Our favorites: Julius Caesar and The Tempest.

Around this time we become interested in “film” as opposed to “movies.” We study editing techniques and cinematography. Rory’s favorite director is Federico Fellini, especially his film, Juliet of the Spirits. Plot has never been one of Rory’s strong points, so I think he relates to Fellini’s amorphous method of storytelling. He is both fascinated and amused by New Wave cinema, Jean-Luc Godard in particular, and draws a poster for an imaginary experimental film called Monotonous. The poster is just the word monotonous written over and over. Even Rory’s encapsulation of the plot (appearing in one of his magazines) is funny: “A bear and some people do things.”

Rory does not draw people. He has developed a shorthand way of drawing bears and seems content to use this template regardless of the story line.

The stranger at the door asks, “Are you Mrs. Hayes? Do you have a son named Rory? I’m afraid there’s been an accident.”

Riding his bike down a steep part of Cortland Avenue, Rory had taken a tumble and collided with the fender of a parked car. Once again: much blood, stitches, and, because he has a concussion, an overnight stay in the hospital.

That night, in our kitchen, Mom tells me, “I know it sounds dramatic, but I’ve always felt that Rory is never going to make it to adulthood.”

Mom is dramatic, but this time I can tell that her concern is genuine. She sees me as almost an equal. With Rory, she’s always trying to correct something, to save him, often to adverse effect.

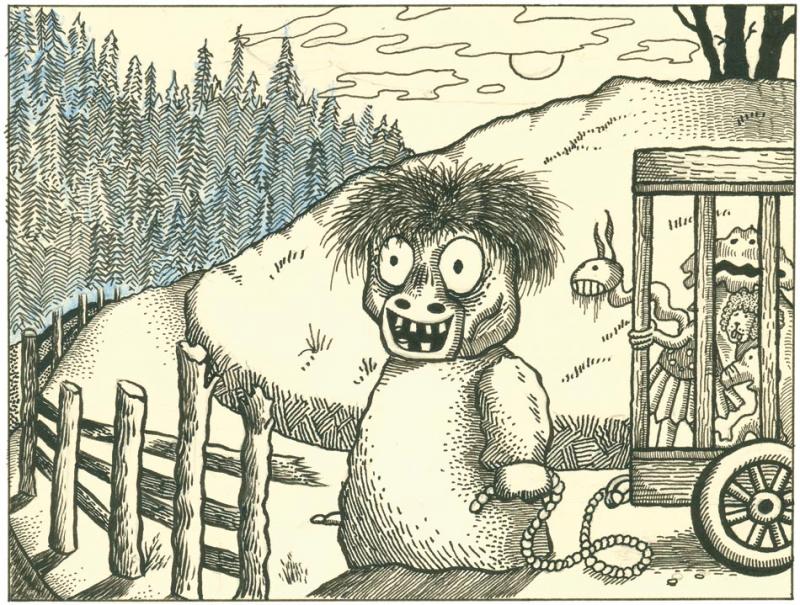

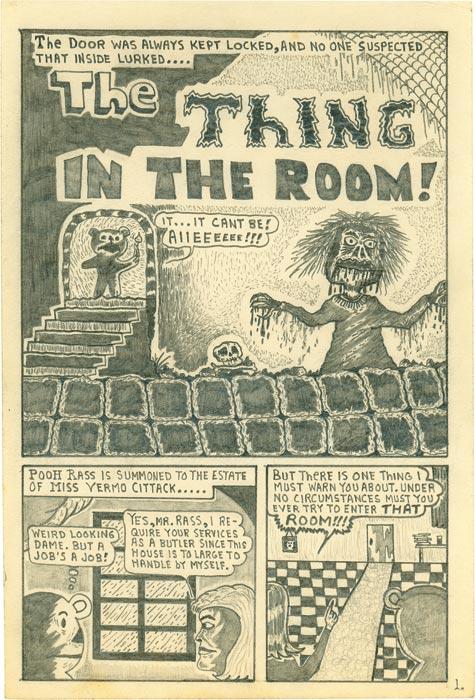

Rory comes home from the hospital with another scar—this one in the middle of his forehead. He recuperates, and we continue working on our imaginary world. I am the more natural artist, but my art is derivative and superficial. Only the stuff I do with Rory has guts. Rory’s work is and always will be his own. Bypassing his conscious mind, it arrives directly from some deep place onto the page, unvarnished and unapologetic. I am aware of this and envious. I begin copying the way Rory draws shadows. For a while our work is so similar that, years later, I will have difficulty telling some of our drawings apart. Nor am I the only one. A few of my published pieces are attributed to Rory, particularly a giant-monster spoof I draw for Bogeyman #2, called “The Rag,” and two panels from the story “The Purple Money Grabber.” In the latter piece, the inks are Rory’s; the pencils, mine.

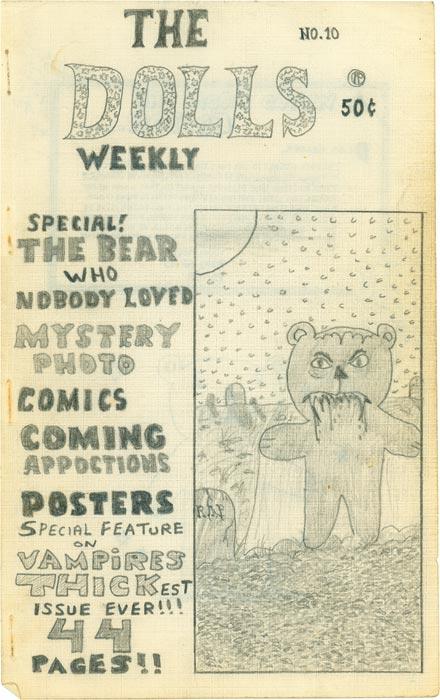

Rory is drawing in earnest now, producing numerous posters, comic stories, and four issues of a small magazine he calls Monsters and Ghouls, a parody of Forrest J. Ackerman’s Famous Monsters of Filmland. His most ambitious project is a magazine chronicling the comings and goings of all our characters: The Dolls Weekly. The bulk of The Dolls Weekly is devoted to discussions of numerous imaginary films, with emphasis on horror and science fiction. But there are also letters to the editor, news articles, biographies, puzzles, poems; even advertisements, subscription forms, and copyright material.

When I am fourteen I buy an 8mm camera, and Rory and I begin filming home movies. Some employ our dolls as actors, with miniature sets and props. Others star the two of us, our parents, and anyone we can recruit. Many are spoofs (What Is It? and its sequel, What Is It Meets What Was It.) Rory loves Pop Art and produces a three-minute film called Andy Warhol, which is nothing but a can of Campbell’s tomato soup shot from various angles. Despite Rory’s later assertion that we produced over a hundred and fifty films, the actual number is closer to forty.

It is summer again—another warm day. I am seventeen, Rory fifteen. That evening, Mom and I come back from the movies to discover that the house is dark and the front door locked even though we’d left Rory at home. He’s not there. In Mom and Dad’s bedroom Dad’s moneybox is on the floor, emptied. Across a framed photo of Dad’s smiling face Rory has drawn an X with Mom’s lipstick. We find Rory crying on the steps out back.

What happened is this: he’d taken a bus to Playland, his favorite amusement park. There, he freaked out and came home, but he had forgotten his key and found himself locked out. A drama ended before it began, really. But this provokes in Rory a mini-breakdown, an explosion of rage that plays out relatively harmlessly.

When Dad comes home in the wee hours, he and Mom talk but decide to let it go. Rory has been arguing with Dad a lot. Our father isn’t a mean man. He never hits or abuses Mom or us. Still, he isn’t a warm person—as stingy with his affection as he is with money. He calls me “Buddy,” but we are not buddies. I can’t recall having a single conversation with him. We’re well fed, well cared for, but not embraced, and Rory’s resentment has an edge. But after this outburst, it seems as though Rory stops being so angry. He grows into a quiet, shy, polite young man. His art is the only evidence of his rage.

When he’s a sophomore, Mom lets him drop out of high school to find a job. After graduation, I, too, make the rounds job-hunting. Mom and Dad aren’t keen on my going to college. They have a distrust of formal education and anything too “establishment.” In their own way, they are hippies before there are hippies. They also want me to start contributing to the household expenses, which I resent. I know I want to be an author-illustrator, so on impulse I cash in a savings bond and buy a one-way ticket to New York City. My goal is to get published and attend Hunter College in Manhattan. Doing this, I believe I am finally shutting the door on our childhood. Six months later Rory follows me to New York.

For a few months we share a room in a small residential hotel not far from Grand Central Station. Later, we find a seventy-five-dollar-a-month, one-bedroom apartment in a Hasidic neighborhood of Brooklyn. I work in the copy room of Harcourt, Brace and World. Rory gets a job as a messenger for Stanley-Warner, a movie theater chain. We still create stories together, even though larger interests now occupy me—continuing my education, exploring my sexuality, and polishing my writing skills.

Rory’s artwork drops off, though he keeps making posters or props for his films. His primary interest is collecting 8mm movies. During his stay in New York, Rory works on three major projects—all 8mm films with accompanying posters, stories, and press releases:

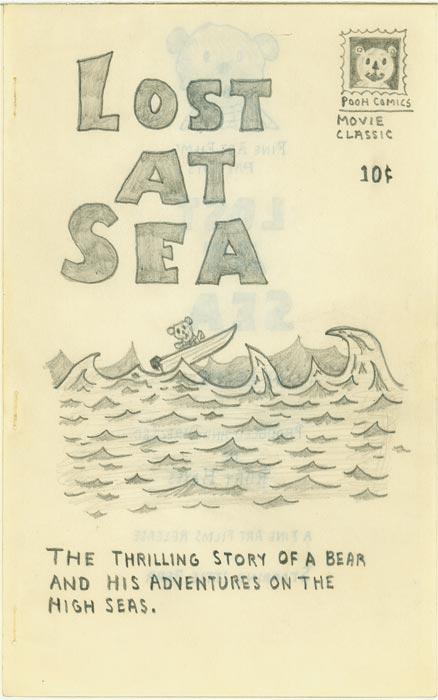

- Lost at Sea

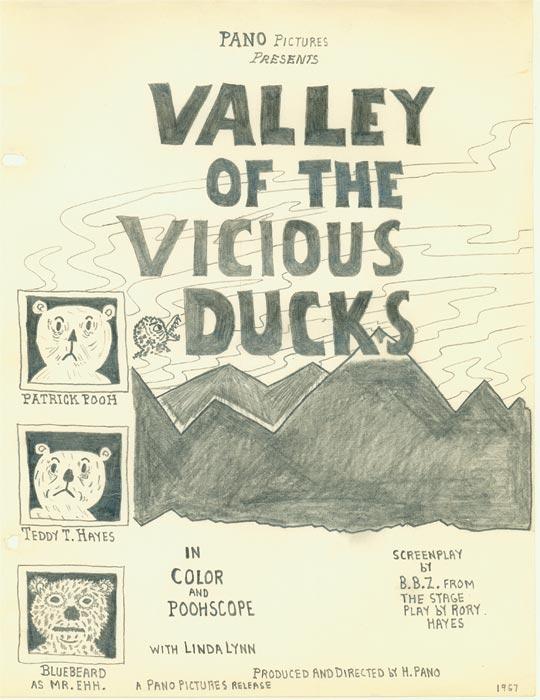

- Valley of the Vicious Ducks

- So That’s Where Demented Wented

All star our doll characters, a few of which have actually traveled to New York with Rory. He also directs me, on our rooftop in Brooklyn, in one of our psycho-killer parodies. I forget the title. The Roof, probably.

After a year and a half, Rory returns to San Francisco and lowers the curtain on the last act of our childhoods. While I continue using our characters and ideas in published books, Rory will go in another, darker direction.

2. Bogeyman

I may not be the best person to speak about Rory’s later years. I lived across the country from him, and each of us had his own crowd. But spiritually we remained close. We wrote letters, sent each other sketches of those same childhood characters. Rory, strapped for cash, sold most of these to Alfred Bergdoll, though I don’t think he passed them off as solely his own. When Rory learned that I was gay, his love for me was undiminished.

Shortly after his return to San Francisco, Rory discovered Gary Arlington’s San Francisco Comic Book Company, on Twenty-third Street in the Mission. Rory and Gary became friends, and he showed Gary a new story he was working on, which was influenced by the old EC comic books. With the emergence of the hippie movement and the anticensorship stance of underground comics, EC was viewed as the standard of free expression. Gary Arlington loved EC and saw in Rory’s work a similar uninhibited energy. He agreed to publish a book of Rory’s stories, if Rory would agree to do them in pen and ink. Rory jumped at the chance. These stories would become Bogeyman Comics.

Bogeyman #1 was a continuation of what Rory had been doing as a teenager, albeit rather more gruesome. It was less an underground comic than a retro take on old horror comics, but it got him noticed. Not everyone admired his work, but most envied its visceral quality. Soon Rory was getting work illustrating a page or two for various publications. And, given the times and the culture, he started using drugs.

I can’t say what got him started—marijuana probably. I do know that by the time I returned to San Francisco in the early seventies, he was into speed, and he later told me that he had taken acid. Drugs seemed to liberate Rory, to let him unleash his demons full force. It was only at this point that he began referring to his art as a release or an expression. Only with Bogeyman did Rory even start thinking of himself as an artist, of drawing as more than just a hobby.

While Rory was always original, his vision was tempered somewhat by what we had shared creatively. Freed from those restrictions and empowered by drugs, he was able to delve into a universe of his wildest imaginings. While he sometimes used our characters’ old names, they held little resemblance to their namesakes. Granny Crackbaggy, for instance, was just a nonsense name, invented before “crack” or “baggies” existed. I used that name in a couple of my early children’s books, something I could never get away with now.

Like most people, I was shocked by Rory’s underground art. My published work, in comparison, remained relatively tame. My drug of choice was marijuana.

What set Rory’s work apart was its intensity. The closest Rory ever came to writing a children’s book was a small comic called Lost at Sea. It was based on an 8mm film of the same name about a teddy bear who takes a small boat out on the ocean. A storm ensues; the bear is lost, then finds his way home. The film alternates between shots taken in our bathtub in Brooklyn and location photography at Coney Island. Rory went out there alone one gloomy day with his camera, the teddy, and a toy boat; he was quite proud of this work. Sadly, like all the movies we made, it no longer exists—but the comic still does. There is nothing violent, strange, or scary about the story—and yet Rory’s panels are among his most dramatic and well composed.

Following closely on the heels of Bogeyman #1, Rory produced a book that was to forever cement his reputation as a deeply disturbed artist. This would be the infamous Cunt Comics. These days Cunt Comics could be the name of a lesbian graphic novel, but at the time (1969–70) it was about as bold and filthy as you could get.

Had Rory not been hanging with a new crowd, he may have been content to go on drawing teddy bears in bizarre situations. Probably, his new friends encouraged him to branch out, to draw more humans, to draw something sexual. Rory, being Rory, took the idea and ran with it.

Cunt is like no other comic book ever produced. Small, almost pocket-size, it eschews storytelling (never Rory’s strong point) for a series of raw, graphic, and frequently violent sequences and single panels. It is depraved work, no question. (The Marquis de Sade would have loved it.) Because of his inhibitions Rory dealt with his fears the only way he knew—through his art. While Cunt seems a work of insanity, I believe it was a means for Rory to avoid insanity, curbing his demons by expressing them. He was not sexist. He was closer to our mother than I was. But it seemed that he was tapping into some hidden well of hatred and distrust of women. He was releasing it like excrement. For Rory, Cunt Comics must have been one huge, satisfying dump.

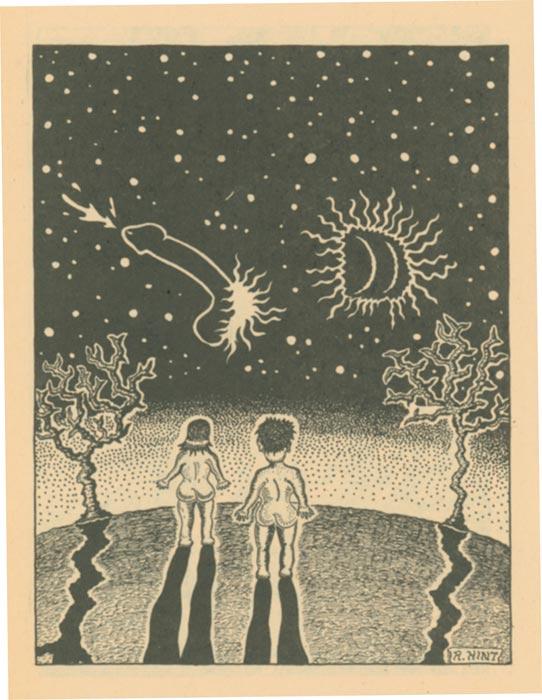

After multiple pages of sex as anger and violence, he comes to the end of the book and what does he show? A single panel of a naked man and woman. They are on a hill, backs to us, looking at the stars. Above them, male and female genitalia are depicted in the heavens as constellations. It’s a serene picture. Gone is the urgency of sex, the frustration, the rage; what we are left with is male and female at their most elemental, spiritual level. It’s as if after a wild ride through hell, Rory had reached an apotheosis. Certainly, he was never again to do anything as visceral and sustained as Cunt. The rage he’d carried since childhood was replaced not by peace but, perhaps, resignation. The works that followed were, at first, strong. Rory wasn’t done delving into his fear and alienation, yet Cunt Comics was an apex as well as a breakthrough. I think it fitting that, shortly before Cunt’s publication, most of Rory’s original artwork for it was destroyed in a fire at the publisher’s offices. The art was consumed and released, as his anger had been. What remained was a slow decline.

There are few childlike qualities to Rory’s underground art. Some images in his panels have a simple, innocent feel to them, but they come from a place far away from childhood. For Rory, the Long Childhood was over. He was entering H. P. Lovecraft territory.

We never stopped being friends, not even in Rory’s last decade, when I was living in New York and he in San Francisco. Due partly to the distance and Rory’s itinerant life, we went for long periods without communicating. He came to visit me about a year before he died. He was asocial and unwashed, practically a street person. I have memories of him sitting on my sofa playing Pac-Man for hours at a time. It’s a familiar story, one sibling spiraling downward because of drug dependency, the other unable to save him.

Rory was too much a coward to deliberately commit suicide. I say that affectionately. For all the gore he drew on the page, he was squeamish. When we were preteens, we came across a story in the National Enquirer about a black boy who had fallen in front of a subway train and been killed. There was a photograph of a policeman holding the decapitated head. This image haunted Rory for weeks. In art, he thought dark and scary stuff was “cool.” But real life was different.

I was visiting San Francisco when Rory died, though we hadn’t yet connected. Mom called to tell me the news. She said that Rory had had an embolism (which may have been the case); she mentioned nothing about a drug overdose. I don’t think either of us was surprised.

Beyond fact and explanation lies the mystery of creation. The best artists, such as Rory, make peace with this mystery and do not question their inspiration or its expression. He drew what he drew because that’s what he drew. I didn’t have his stubbornness.

We grew up in the same household, born eighteen months apart. We shared experiences and fantasies. We had the same stories and the same characters, and yet our art evolved differently, as individual as a signature or a thumbprint. I can’t say why this is, any more than I can explain why I am gay and Rory was straight. I do know that had we not had each other, had Rory or I been an only child, it’s doubtful either of us would have become an artist. We drew for each other, spurred each other on. Rory is still present, as he will always be, in every story I write, in every line I draw. Ultimately, they are all for him.