Watch the suit run, the boys chasing him. War orphans, some of them, others carrying their younger siblings, polio afflicted, across their shoulders, hands outstretched. “Money, mister,” they beg. Clutching his jacket, his shirt, they are a locust swarm of impoverished children driving this foreigner (diplomat, aid worker, contractor, who knows?) to madness. Shirttail flapping, he tosses money from his pocket, flees past the stylish storefront mannequins of Crystal Light Fashions and Jacque Fashion, past the trays of cream puffs in the windows of Sheikh Nabal Bakery, and dodges around the red-striped concrete security barriers at Safi Landmark Hotel and Suites.

At last he bursts through its gilt-framed doors. The lobby yawns before the boys and they tilt their heads back and follow the diamond-shaped glass elevator as it rises eight floors above the marble lobby. When the doors close again, their reflection hangs trapped in glass. “Tomorrow, you give us five dollar,” one of the boys shouts.

Armed guards, scowling and agitated, shoo the boys back with the duct-taped butts of their battered Kalashnikovs, “Buro! Buro!” Go! Go! And the boys scatter, the suit’s money choked in their hands. They proceed down the road, across the street from the new, blue-tinted Kam Air building. They squint, eye one another, ready to steal from the group’s weaker members if the opportunity presents.

Then they see me and stop. “Nay, not this outsider,” my Afghan colleague Aziz tells them in Dari. “Bugger off.” Our companion, Ahmad Shah Marofi, echoes the soldiers’ order: “Buro.”

We are looking for a twelve-year-old boy named Hamid, one of Ahmad’s students from Aschiana—literally “the nest,” a school for street children. Ahmad tells me that Hamid knows everyone on the streets of Kabul. I’m hoping he can help me find my boys, my six war orphans, my old students. When I last saw them, they were thirteen. We finally find Hamid, and I show him the photograph from 2004, but he just shrugs. Maybe he knows them. He can’t say for sure. He crooks a finger, and I follow.

Ahmad does not recognize them, either. “I’m sorry,” he says. “I don’t know them. We see so many.” He pats my shoulder, and his resigned look tells me what I already know. Look around: The streets of Kabul are filled with orphans. I put the photograph away.

I left Kabul in October 2004, when Hamid Karzai became Afghanistan’s first democratically elected president, when what most of us hoped would be a successful democratic regime was launched in the wake of the Taliban’s defeat. As a journalist, I had turned my attention to Iraq, the next immediate disaster and career-making opportunity. Afghanistan, I reasoned, could do without me. There would be much less violence, much less poverty, and my boys, I thought, could do without me, too. Judging by the state of things today, I was wrong. This spring I watched an evening report on CNN about the inroads the Taliban had made around Kabul, and I decided to come back, to see if my optimism had been misplaced. Mostly, I felt guilty. I needed to find those boys.

When I arrive at my Kabul hotel, the staff warns me not to drive outside the city limits, where suicide bombings, kidnappings, roadside bombs, and violent crime are part of everyday life in this Texas-size nation of about thirty million. The Taliban move with impunity throughout the country, I am told. International aid organizations travel in heavily guarded convoys whenever they have to navigate undefended territory. The old regime, people whisper, is a threatening shadow behind every tree on the highway. The violence caused by the continuing insurgency took an estimated 3,700 lives in the last year alone. Fifty thousand foreign troops, led by US military and NATO forces, have been unable to quash the resurgent Taliban. Civilian casualties—including children wounded or killed in NATO forces’ retaliatory strikes against insurgents—have only increased resentment toward foreigners.

The lingering effects of the Taliban’s rule within the city are even more palpable. Children beg at every corner. Their parents—a few lucky kids still have parents—struggle to find any kind of employment. In Kabul, nine thousand street children and countless slum-dwellers live in appalling poverty. Instead of attending school, one in three children must work to help his family survive. According to Afghanistan’s Independent Human Rights Commission, the prevalence of child labor is creating a generation of illiterate Afghans who will likely remain trapped in poverty. The only people bringing money into the country are misguided aid workers, former warlords evolved into drug lords, plutocratic economic opportunists, and corrupt administrators. The rich suddenly have access to a market the Taliban denied them, but the poor remain as poor as always.

The world promised reconstruction to Afghanistan; it was to be thrust from the medieval rule of the fundamentalist Taliban into the booming twenty-first century. However, progress has materialized only in scattershot fashion across this country where elite villas, five-star hotels, and fabulous malls for a very few take precedence over roads, schools, and farms. Hovels were bulldozed to make way for expensive housing for Kabul’s wealthiest residents—top government officials and their lackeys. Hundreds of refugee families living on government-owned land in the posh Wazir Akbar Khan neighborhood were ejected from that prime real estate. Mansions and malls tower over mud-and-burlap vendor stalls in a clash of priorities between, on the one hand, a tribal, Islamic culture and, on the other, secular, gotta-have-it, drug-infused venture capitalism. The latter influences everything, including international aid organizations.

Daily, Afghans thread their way through a traffic jam of abbreviations emblazoned across Land Rovers: UN, UNESCO, UNDP, ACF, MACA. No reliable figures exist on the overhead of the three hundred and fifty Kabul-based aid agencies, but indirect signs—air-conditioned Land Rovers, Nissan Pathfinders, Toyota Land Cruisers, and luxurious residences—suggest a high figure. The average cost of maintaining a foreign UN employee hovers around two hundred and fifty thousand dollars. Every time an aid agency convoy leaves Kabul, they spend as much as twenty thousand dollars on security teams. Add to that the soaring cost of monthly rentals—as much as fifteen thousand dollars—and you have a tidy sum devoted to their upkeep.

Despite these few showy trappings of prosperity, most of Afghanistan still lies in ruins—along with the optimism that first greeted the US-led military coalition six years ago. The US strategy in Afghanistan has even unofficially allowed some Afghan warlords, recruited by the Bush administration, to fight al Qaeda and the Taliban for control of Afghanistan’s flourishing opium trade.

“Who doesn’t want money?” says Shirish Ravan, project coordinator for the Kabul office of the Illicit Crop Monitoring Program of the UN Office on Drugs and Crime. “The money is guaranteed. It doesn’t rot. It’s not like fruit but more like gold.”

These warlords use profits from drug trafficking to fund their armies and amass power, further weakening the nearly impotent Karzai government—all under the auspices of the US war against terrorism.

In a way, I feel like America: I made commitments, got those boys thinking about their futures, then jumped ship. When I wrote Bro, my former translator, for news of the boys, he replied that he had not heard from them. “You don’t have to worry,” he said. “They expected nothing from you.” And I didn’t disappoint them.

Our relationship had evolved gradually. The boys sat outside my hotel with their shoeshine boxes, and I gave them candy. One afternoon, I took them to lunch. I bought them meals every day, though I never learned to pronounce their names correctly. Instead, I used nicknames. There was Mr. Bakshish, pronounced baksheesh in the Dari language (an expert at begging for free tips); Mr. Ten Dollar; Mr. Meat; Mr. Gigolo (because of his cool sunglasses); Mr. Nike (he had a sports jacket); and Mr. Chocolate (he loved Snickers bars). Eventually, I enrolled them in the Aschiana school. Ahmad Shah Marofi was their teacher. I even talked Bro into helping them with their homework. But I did it for myself as much as for them. Amid daily cries of “Money, mister!” and clawing hands of desperate children ghostlike in the fumes of diesel exhaust, befriending six impoverished boys helped keep me sane.

On my last day in Kabul, I gave Bro four hundred dollars for their meals and to help with school. However, he had a family to worry about, a new job to find in my absence. Shortly after I returned to the States, he wrote and asked for more money. I knew he could not have already spent on the boys what I’d given him. I don’t begrudge him putting that money to other uses. What were war orphans other than a common sight to Bro, a man who had survived the Russian occupation, civil war, the Taliban, and the coalition’s invasion? He needed help, too, and I didn’t blame him, either, for testing my generosity. But I also refused to send him more money, and with that decision ended any news of the boys.

Back home, I thought of them constantly, wondering if I had actually done them more harm than good. I had given them reason to have expectations. To expect a daily meal. To expect help with school. To expect attention and encouragement. And then I left.

Aziz lights a cigarette, offers one to Ahmad and me. When I began planning my trip back to Kabul, Bro, who now worked in a hospital, suggested that I hire his unemployed father, Aziz, as translator. His mobile phone rings and he answers a call from his youngest son, Nabil, who asks if we’re okay. Everybody is buzzing, because three Pakistanis were arrested this morning, strapped to the hilt for suicide bombings. When they were caught, just six minutes and fifty-two seconds were left on one of the timers. I was with the manager of my hotel when I heard the news. We were in the garden, standing by pink rose bushes and a broken stone fountain, listening to the radio while I waited for Aziz and Ahmad. The hotel manager shook his head, told me it was very difficult to combat this “procedure.” If someone wants to kill himself, what can you do?

Kabul offers the illusion of bustling normality; a suicide bomber hustling through intersections seems an impossibility, a paranoid’s delusion. The capital sits on a barren plain at six thousand feet, with windswept mountains, ten thousand to sixteen thousand feet high, to the north, east, and west. Dust-clogged, rutted, potholed streets weave through crowded markets, open-fronted mud huts housing butchers, carpenters, auto repair shops, photography studios, and satellite tv stores, all on the same block. Garishly decorated, diesel-spewing taxis and buses, donkey carts carrying fresh vegetables, and nomadic shepherds leading caravans of camels and herds of sheep and goats vie for space on roads so congested it can take an hour to drive two miles. Sandal-clad men rush about carrying wads of fifty-to-the-dollar afghanis, buying everything that wasn’t available under Taliban and Russian rule: satellite dishes, tvs, laptops, satellite phones, cell phones, and used Toyota cars with Pakistani plates and mix-and-match tires. No credit cards, cash only. Electricity runs intermittently, generators hum 24-7. Suited up in flak jackets, sunglasses, and black boots, security contractors walk the streets with a gunslinger’s strut.

Plunging into this jostling intensity, Aziz, Ahmad, and I follow Hamid toward the bazaar. We look for my boys in the harsh glare of midmorning where summer temperatures have already reached ninety degrees and hot winds speckle our bearded faces with the grit of diesel exhaust and dust. Hamid seems unfazed by the heat or his daily schedule of school and street hustle. He has attended Aschiana for three months. All of its students survive, as my boys had, shining shoes, washing cars, begging, or, like Hamid, selling plastic bags to shoppers at five cents apiece.

Last year, a Dubai businessman bought the land the school had rented since 1997 and told Aschiana they must leave to make room for a new InterContinental Hotel. Karzai signed an executive order giving Aschiana an acre of downtown land. But a US company called Red Sea Engineers & Constructors had taken over the land and built a wall around it, saying it was part of twenty-nine acres the company had leased to build a gated community of upscale homes for Western aid workers. Under pressure from Aschiana’s backers in Washington, US ambassador Ronald Neumann pushed Red Sea to cede the acre to Aschiana.

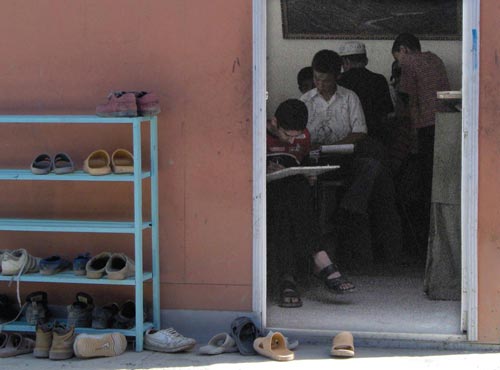

Now the school has land but no money with which to build on it. A small compound of four pink brick buildings in downtown Kabul provides new inadequate quarters for the more than five hundred children who burst through its doors six days a week. “Everyone talks about the children,” Ahmad says. “They talk of them as the future of the country, but it is just talk.”

And foreign aid money is called “aid,” even though it rarely provides any help. Last year, Karzai conceded that much of the $13 billion in foreign aid pledged since 2002 was “wasted on high salaries, large overheads, luxury cars, luxury houses that Afghanistan cannot afford at all.” Karzai would have been better off having said nothing. His complaints only showed his government’s increasing ineffectiveness and isolation.

Growing public discontent laces tea-shop conversations with venom. Afghans dismiss Kabul as the “yellow pages” of aid organizations. They call Karzai “America’s dishwasher”—a demotion from his previous title, “the Mayor of Kabul,” a ruler with little authority outside the capital. Now Kabul’s citizenry won’t give him even that much credit.

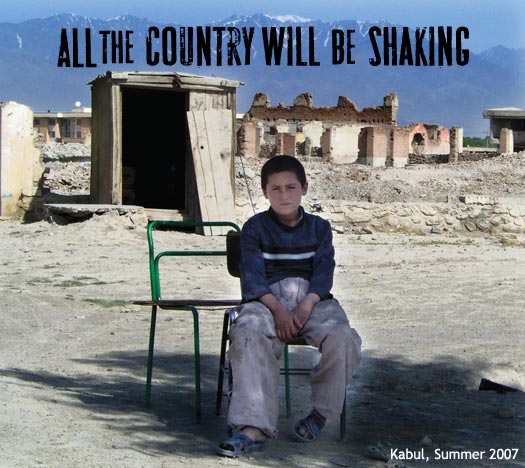

“Kabul is the heart. If the heart is diseased, all of the country will be shaking,” Aziz says. “Afghanistan will be fucked, basically.” Hamid stops from time to time so I can show my photograph of the boys to children who clutch at me for money. Then we move on. He takes us down a dusty sidewalk past the Iranian Embassy and UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Overcrowded buses sag and jobless men sit lethargically on a grassy median strip, staring trancelike into the gritty air. Above us, an orange billboard promoting a $600,000 lottery through a local mobile phone company catches the sunlight.

“Will you invite us to work?” a man shouts to me. “I have already invited someone,” I say pointing to Aziz. “Today, yesterday, no job,” the man tells me. “I have no money. My son is in school and needs books.” I offer him ten afghanis—about fifteen cents. Aziz puts a few more coins in my hands. I give the man the money. I show him the picture, but he ignores it, picks at the coins with the tip of a finger.

Swiss chalets, beauty salons, amusement parks, and boutiques for the newly affluent don’t provide what the majority of Afghans need: jobs. Most of the foreign companies descending on Kabul bring their own site supervisors and salaried workers with them. Afghans fill the grunt positions: ditchdiggers, cement mixers, cleanup crews. Few companies train them to fill less-expendable positions. When the work ends, so does the job. Suicides by hanging and self-immolation have increased as unemployed men sink into despair.

“Five days ago, I got a job and cleaned a house for a farmer,” the man tells me. He closes his fist around the coins. “I worked eleven hours. I was paid three dollars. It was not enough.” He watches us go, hand outstretched. Hamid cuts through the downtown bazaar, stepping around blankets strewn with spices, fruits, and nuts. Used blue jeans and denim shirts donated to aid organizations have somehow found their way to the market and hang along steel railings above the drought-drained Kabul River. Pools of stagnant water send up a stifling funk, and Aziz exhales cigarette smoke in my face to rid my nostrils of the rotted odor while war widows in tattered burqas sit in the mud and clutch at my ankles. Their children, their faces caked with dust and cracking at the corners of their mouths, stare wide-eyed at the parade of sandals, boots, and shoes inches from their faces.

“You promised to take me to Fahim,” a man yells at me outside the warped doors of his pharmacy.

“What the hell is he talking about?” I say to Aziz. “Why would I have promised to take him to the former defense minister?”

“He mistakes you for someone else.” Every white face is presumed to be American, and every American is presumed to have the ear of the government.

“We don’t want you, go back,” the pharmacist warns. “You made a promise. What has happened to your promise? You remind us we are all in the background. Afghanistan is like a jail. Our guard is NATO. Our warden is Karzai.” Aziz takes me by the arm.

“We all have limits of how much humiliation we can take,” the pharmacist shouts as Aziz hurries me along. “If I eat too much of it, I will vomit it back.”

The sun burns the back of my neck and we stop for water. Boys gather around me, curious because I am on foot with two Afghans and no vehicle in sight. I look at them closely, but they are not my boys. I pass around the photo. Nothing. They don’t know them. More angry men I don’t recognize demand I fulfill promises I don’t think I ever made.

“When there was civil war here, all the world was quiet,” Aziz says, gripping my elbow. “Now the world is getting quiet again, but it is worse. The people are angrier, hungrier than before.”

We wend our way through the crowd of distorted faces jockeying for my attention. Hamid climbs a steep, narrow path leading up a mountain toward adobe houses. After an hour, we reach the top and enter a square mud hut. Hamid kicks off his sandals, crosses a thickly carpeted floor, and withdraws from behind a curtain a plate of naan—long, snowshoe-shaped flatbread. He greets his mother. She watches him eat. She has severe rheumatism and cannot work. Hamid’s father died three years ago. Natural causes. Hamid dropped out of regular school to work and help provide for his family. I tell her about the boys, but she remains focused on Hamid. She expects him to earn one dollar a day, enough to buy seven loaves of naan. “Is naan enough?” I ask.

“No, it is not enough. But with tea it is enough.”

When he finishes eating, Hamid descends the mountain, leaping from one boulder to the next, and I slide on my ass after him. Back on the street, he pauses at vendor stalls, offering his bags to the Westerners who bargain over small piles of tea, soap, and nuts. I try to show the boys’ photo, but merchants wave both Hamid and me away. I am discouraged, but Hamid walks on, undeterred. Above us the sky darkens and the wind picks up and knee-high dust devils unspool around us. We raise our faces, feeling the first hints of rain. Soon the heavy drops pick up and gather into a downpour. We duck under the umbrella of a fruit wagon. Shoppers run and Hamid chases after them, his hand-me-down pink polo shirt clinging to his drenched body. A woman buys a bag from him, covers her head and hurries away. Then I lose sight of him in the wet torrential blackness that consumes the market.

At night, I dream of the boys. I dream I am with them in the back room of the pharmacy where Bro’s brother works, where we used to tutor them. We greet one another with the high-fives I taught them, then go over their assignments. Bro corrects their Persian, then I walk them through their ABCs and simple phrases: good morning, how are you, have a nice day. The boys, eager for lunch, look at a clock. We give their mothers rice and beans when they do well, as a way to keep them in school. But I tell Mr. Chocolate I will not feed him today or give his mother food. He dropped out of Aschiana to hustle the streets full-time. His father was killed in the fighting—all their fathers were—but an education, I insist, would provide more for him than polishing shoes. I dismiss him, and he walks out the door into sunlight and disappears.

I begin to wake up, linger in half-sleep. My boys stand in the middle of the road and wave. I watch them shrink in Bro’s rearview mirror. I’ll be back very soon, I call out on my way to the airport. I’ll be back very soon.

At midday, Aziz and I sit in Red Hot ’n’ Sizzlin’ Restaurant, part of Red Sea’s gated community. I am trying to decide on our next move for finding the boys, but the prices distract Aziz from our conversation. “A Pepsi is one dollar,” he whispers. “In the bazaar you could get four for that.” He compares other prices, seeing only the amount of food he could buy with another man’s disposable income.

“I’ll buy the Pepsi,” I assure him.

Enclosed by concrete walls and barbed wire, staffed with two checkpoints, the Red Sea complex, like the biblical Red Sea, hopes to be an avenue of escape for expats. Thirty-two of one hundred planned one- to three-bedroom houses have been built near the rock-strewn land ceded to Aschiana. “Contractors come to town, they rent a house and have to share a bath,” an aid worker told me earlier. “That’s not too nice. This is an option.”

Earlier in the day, I had met with Red Sea president Roy Carver. As he offered me a chair, an office manager brought news of a bomb threat. Very routine, Carver assured, waving me into my chair.

“Have you heard the joke? If you want to be safe in Kabul, move into the US Embassy.”

I shook my head to show I didn’t get it.

“It’s a routine target for insurgent rockets,” Carver explained, “but they always miss.”

This was nothing more than an annoyance. He would be shut in for a few hours and production time would be lost while the threat was investigated. Overall, however, the rising instability has not hurt business at Red Sea but helped it. More and more people are coming into Afghanistan to train its fledgling police and armed forces. They will expect places to live and pleasurable escapes. International contracts for the construction of roads, for power and water projects around Afghanistan mean more prospective tenants for years to come. “Now Pakistan, that will be a big goddamn mess if that ever blows,” Carver said, walking me out.

Across from Aziz and me, expats crowd a long rectangular table and order beer and drinks. The green walls and redbrick archways resound with their laughter. Black polo shirts with the Red Hot ’n’ Sizzlin’ logo hang tacked to the wall; one of the expats asks to try one on. Another man pulls at the corners of his eyes to imitate the Asian features of their Afghan waiter. I glance at a menu of chicken fried steak and Texas T-Bone. “What are chicken wings?” Aziz asks.

The door opens with more customers. Behind them in the parking lot, smoking cigarettes beside Land Cruisers, stand Afghan drivers wearing the traditional shalwar kameez. They will wait while their employers finish their dinners and drinks. Seen as potential terrorists, Afghans can’t enter some restaurants, stores, whole sections of the city that are frequented by foreigners, not even when their Western bosses accompany them. Aziz, in slacks and a blue dress shirt, his gray hair combed to perfection, believes he was allowed in with me because he was mistaken for a foreigner: perhaps an Indian or Pakistani presumably associated with an NGO.

“What does that say to the people?” he says. “It says this is an occupation.”

Aziz makes his observations almost absently, without so much as looking up from his menu.

“What are nachos?” he asks.

I raise the idea of a road trip. Mr. Bakshish had family in Bhali Kot, a village outside Jalalabad known for growing poppies. I want to drive there and show his picture around. Aziz would prefer to stay put. The Kabul–Jalalabad road was recently paved and the five-hour boulder-strewn drive has now been reduced to two hours. But no matter how fast traffic moves, you can still find yourself alone in Taliban territory, far from any checkpoints and mobile-phone towers. “If the stupid Talib stop us,” Aziz says, pausing to sip his dollar Pepsi as if it were champagne, “we will be in deep shit. Do you feel lucky?”

In the morning, Aziz races along the blacktop of the Kabul–Jalalabad road as if nothing else matters but the sheer joy of driving on clean pavement. The novelty of this newly repaired road has caused nearly as many deaths as have insurgent attacks. Afghans drive without caution. Any smooth surface beneath their wheels is an autobahn freeway intended for unrestrained speed. Pass on a curve into oncoming traffic? Why not? Squeeze a car off the road to get around them? Inshallah, we will make it. The wrecks of lost gambles lie crumpled in rocky gorges five hundred feet below, littered with scraps of snagged clothing and bleached bones.

Afghanistan is a beautiful, rugged country—like the American Southwest with mountains the size of the Rockies. Barefaced cliffs trickling with waterfalls tower into the sky, a white haze of scorching sun. There are rivers churning only a few feet away. Boys on inflated trash bags ride the bucking waves. It would be easy to think war no longer exists here. But my mind keeps running over the 3,700 people killed in 2006, the insurgency, the roadside bombs, the kidnappings.

We pass through Sarobi and the last military checkpoint before Jalalabad, and then approach Laghman Province, a Taliban stronghold. Mud-brick compounds shrink from the road behind a line of trees and the rock-strewn bed of a dried stream. Creepy. I don’t see a single person. Aziz drums the steering wheel with his fingers and mutters a quick prayer.

Next we enter the ghost town of Sarakhan, where until recently the Taliban had staged attacks against government forces. To halt the attacks, the Afghan National Army evicted everyone from the village. A few worn blankets hang in the windows of vacant houses and mongrel dogs lounge in fire pits that haven’t been lit for months. I notice a crooked line of rocks in the middle of the road. I look up at the mountains to see where they might have fallen. Aziz looks too and then back at the road.

Without warning and accompanied by an ear-wrenching grinding of gears, Aziz rips the stick shift into reverse. My head snaps forward and back. He swerves around a bus looming large in the rearview mirror and a truck beeping wildly as we nearly ram into it. Then he stops. The car idles hotly. I hold the back of my neck. “Jesus, Aziz!”

“I am back driving. The Taliban blocked the road!”

The truck we nearly hit drives around the rocks, as did the bus. We wait. Soon I see them round a curve passing a horse-drawn cart loaded with firewood. No gunfire. No explosions. No snipers.

“It’s okay. Just some rocks off the mountain.”

“Yes, I think so, too,” he concedes. “But if we smell a problem, we go?”

“Yeah, man,” I agree, “but chill on the back driving.”

Blind landowner Qari Mohammed Shah sprawls on a cot under emaciated trees. The cot sags under the weight of his considerable bulk. Two naked infants sleep on flattened cardboard at his feet. He spits without moving and wipes sweat from his balding pate while two boys stand behind him and wave scarves to cool his neck. He sighs the bitter breath of seventy years and tosses nuts into his mouth, rolling them off long, yellow fingernails. The farmers who rent his land sit with their families on the ground around him, passing a plate of watermelon. They examine my picture of Mr. Bakshish, shake their heads, and describe him to Shah, who listens, staring blankly into the sky. Like the others, he knows nothing about the boy and spits again with decorous precision.

“I have enough boys to worry about,” he says and sweeps his hand toward the noise of the children. His toothless mouth collapses into each word he utters. He tips his head back for another handful of nuts, air from the fanning scarves cooling his neck. “Who is this boy?”

“Someone I helped.”

“Help these boys here. How will they eat now that the destroying people have killed the poppy?”

I pocket the picture of Mr. Bakshish and look at the vast shorn fields around me rustled by a hot breeze. Last year’s bumper crop of poppies, from which opium and heroin are made, was grown in twenty-eight of Afghanistan’s thirty-two provinces. The crop yielded more than $3 billion for drug traffickers and farmers, more than 90 percent of the world’s heroin. A farmer can earn between $600 and $1,000 for every two pounds of opium, compared with one dollar for the same amount of rice or wheat.

Soldiers guarding the Jalalabad governor’s office admitted to me that they rarely interfere with poppy farmers. Narcotics officers, they said, only destroy a few acres now and then to pacify the government and the demands of the West. This year, it was Qari Mohammed Shah’s unwitting turn to participate in the crackdown charade. In May, government agents destroyed ten acres of his poppy crop. He now owes $2,000 to the drug trafficker who advanced him poppy seeds. Shah will have to sell some of his land to pay his debt.

“The destroyers escaped back to their offices, but we will look for them. The next time, when a group of destroying people come, we will fight back. The Taliban tells us the Americans want to deny us our livelihood. I believe them.”

The celebratory vision of the future beyond the overthrow of the Taliban has now shifted like a mirage. People forget it was the Taliban that successfully brought the drug trade to a temporary stop by arresting poppy farmers. Disappointment has recast history. These days, Afghans praise the Russian occupation as a time of employment. Security was high and the cost of living low, under the Taliban. Current hardships have led to the strengthening conviction that Afghanistan’s problems—past, present, and future—stem from Western interference. In the game of political one-upmanship between the insurgents and the government, the bad guys are winning. Then again, who the bad guys are depends on whom you ask.

“We want to grow poppies,” sixty-year-old farmer Abdul Wahid says. “What else can I do? I am jobless. I know one man who threw himself in a river and drowned, he was so sad they destroyed his poppy crop.”

Wahid points at a field of watermelons and decries it as a waste of time. Blind Shah faces the same direction and pats his knees. No money, they both agree. Watermelon is just something sweet to ease the overbearing heat of the day. Shah sighs and pats his stomach, and a boy brings him another plate of nuts.

“If you find your boy, you tell him he can only fight,” Wahed says. “Afghans don’t have power. Our government is under pressure from the West. It doesn’t have power. We are both weak. When we fight, the stronger of the weak will prevail.”

On the return trip to Kabul, Aziz seems more relaxed, happy to leave Jalalabad, and the threat of the Taliban, behind us. I am disappointed no one recognized Mr. Bakshish but not surprised. It was a long shot. Aziz ignores my mood, comments enthusiastically about the novelty of white dividing lines that separate north- and southbound traffic. Much better than the mortar casings that used to separate lanes in Kabul.

We get stuck behind an American military convoy. A soldier sits behind a .50 caliber machine gun. He raises his hands, won’t allow any drivers to pass his armored vehicle. We creep along at ten miles an hour. Aziz and I chafe in the sweltering heat. Reading the car thermometer, Aziz tells me, “One hundred five.” He speeds up, but the soldier swivels the gun toward us and waves us back. Aziz slows. A UN Land Cruiser passes us and proceeds toward the convoy. The soldier waves it by.

“NGO,” Aziz says. “Why don’t you tell them you are journalist and maybe we can go, too?” He speeds up to get closer to the soldier so he can hear me. I lean out the window, open my mouth, but the soldier cuts me off.

“Tell your fucking hajji driver to back the fuck up!”

I slip back into the car.

“I heard,” Aziz says.

In the evening, I sit in the garden of my hotel. A suicide bomber has killed ten people near Kandahar—six of them children—and mandatory curfews have been imposed on the staffs of aid organizations staying here. Conducting loud conversations, they drink beer and fill the round tables scattered across the watered lawn. Other guests sit beneath straw overhangs or loiter on the stone walk. A cook grills kabob. Near him, two men sitting beside a cage filled with chirping canaries discuss writing a grant. “We have to include a salary for a spokesman,” one of the men insists. “I love proposal writing,” his colleague gushes.

The man renting the room next to mine sits outside sweating from an evening jog. He complains that his new running shoes cut into his heel. He needs to break them in slow, slowly—as the Afghans say. He laughs. He introduces himself. Hans, a German. He advises the government on agricultural projects. He wipes his face and complains of the lack of coordination between agencies. The Europeans hold back, afraid to get too involved, while the Americans barge ahead without consulting anyone. The Afghans ignore them both.

“What are you doing here?” he asks.

I tell him about the five boys. He does not hold out much hope that I will find them. The chances aren’t bad, he says, that at least one of them is dead by now and another is a jihadist. “You never know. It will be interesting to see how things will look ten years from now, eh?”

I imagine the boys as jihadists. It makes a sad kind of sense. The streets of Kabul remain crowded with the human detritus of the so-called war on terror—children orphaned by Russian mines or the insurgent tribal warfare that persists in the provinces. A couple of new water wells, a paved road, or a clinic built by American aid agencies—as well-intentioned as each effort may be—does little to help thousands of children who roam the streets or suffer as child laborers. Schools, hospitals, and orphanages across Afghanistan have been built by American troops and with other international assistance. Yet, as Lex Kassenberg, of the aid agency CARE International, told me, “The successes are not proportional to the amount of money pouring into the country.” A $4 million fund for school construction remains unspent, because the land intended for twenty new schools was seized by Western interests. More than half of the government schools in Kabul have no buildings and instead use rented space or tents.

Before the US-led military coalition invaded Afghanistan, President Bush told the Taliban government that if it turned over the perpetrators of the September 11 attacks, he would not take action against them. He and other Western leaders had little choice but to make token nods toward reconstruction once the war began, if for no other reason than to establish the basic infrastructure for their troops and to pacify a nation. But meeting basic human needs was never a primary or even a secondary motive, never playing even the rhetorical role it would in the lead-up to the Iraq war. Afghanistan remains first and foremost a military operation. The ideal scenario for the administration was wiping out al Qaeda and the Taliban, propping a puppet government, pontificating vaguely about ongoing assistance, and getting the hell out. The insurgents, however, have not been accommodating. The US is stuck fighting an increasingly bolder opponent on ruined roads, amid shattered hospitals and vacant schools.

As recently as this summer, the International Committee of the Red Cross called for massive amounts of emergency humanitarian assistance for Afghanistan, but many officials feel such a program would draw attention to the failures of the last six years as well as to the empty promises of development. Therefore, virtually no one expects action on the recommendation.

Amid all this, put yourself in the place of my boys: What would look better to you? A jobless future or a Kalashnikov and the power and prestige that comes with it?

Day after day, Aziz and I follow Hamid on his rounds. On this morning, he pauses at a burlap shack across the street from the Safi Landmark to offer a plastic bag to a woman buying tea. She ignores him and he moves on. Aziz crosses the street to buy cigarettes. The young man selling tea glances at me, turns away, and then looks back. I wait for Aziz and contemplate the cracked sidewalk, anticipating an appeal for money from the tea man.

“Mal … co … ?” he says.

We stare at each other. He’s about my height, wearing a filthy T‑shirt and dust-covered jeans, hands stained from charcoal used to heat water. Rail thin. He slips on a pair of sunglasses.

“Gig … ? Mr. Gigolo?” I say.

An embarrassed smile creases his face. He grips my hand and shakes me by the shoulder.

“I, I … saw you!” he says. “I saw you! You now come back? Long time.”

I say nothing. He shows me a photograph a colleague of mine had taken in the Herat Restaurant: Mr. Gigolo, the other boys, and me, eating lunch. We grin at the camera. We’ve both been carrying around photographs of that time. Mr. Gigolo offers me a cup of tea. I offer to pay him, but he waves my money away.

Aziz returns, but Mr. Gigolo ignores him, lost in the photo, his expression darkening.

After a moment I tell him, “I had to leave. I’m a journalist, not a teacher. I should have explained that better.”

He stares at the ground.

“You don’t understand, do you?” Aziz asks.

“No,” Gig replies.

I sip my tea, avoid looking at him, until finally I say what I should have said immediately. “I’m sorry.” He frowns, shrugs. Finally he stares past me and says, “You was … nice man.”

I make plans to meet Mr. Gigolo for dinner. He will bring Mr. Nike and Mr. Meat. He has not seen Mr. Ten Dollar, Mr. Chocolate, or Mr. Bakshish for more than a year. Perhaps they moved to Pakistan. He can’t say.

In my hotel room I sit on the bed and thumb through a book. My fan won’t start, and there is no breeze through the open windows. I stand up. I don’t hear a sound. The canaries, chirping when I walked in moments ago, have fallen silent. Then I feel it, a wave followed by an explosion that throws me to the floor. I reach out with my hands until I can get back on my feet. Dizzy, I half run, half stagger to the sidewalk and see, across the street, men fleeing. I trip and fall face-first into the lap of a beggar on the sidewalk. She screams, and I push myself back to my feet. My ears feel wedged with cotton. Women in burqas, begging only moments before, let out piercing wails as they rock back and forth. Then they, too, flee. The street empties in minutes. Not a car or person in sight. Only the solitary clop of a donkey pulling an abandoned cart of firewood disturbs the sudden silence.

I run in the direction of the blast, past vendors peering out of their stalls at a black smudge in the sky. Other people start off in the same direction until, soon, a small crowd of us jogs down the vacant street. We stop at a dirt road cordoned off by police. Before us, contorted and charred, stand the smoking skeletal remains of a police academy bus. Blood stains the ground. Fist-size pieces of flesh lie among the rubble and torn clothing. I hold my stomach and look away. The police, near panic themselves, shout until their faces become distorted with rage. They push and shove us with the butts of their Kalashnikovs until we back away.

The morning after the bombing, I pack for my return to the States. Boots, shirts, pants, socks, sandals. On my shortwave radio I hear a BBC reporter say that yesterday’s blast was the deadliest attack in Kabul since 2001, and the second suicide bombing in the capital in twenty-four hours. At least thirty-five people, mostly police cadets, were killed; about forty more were seriously injured.

Aziz is right. The heart of Afghanistan is indeed sick and the country now is duly shaken.

“Yesterday showed we are in deep shit,” he says.

He rummages through my wastebasket for plastic bottles, packets of aspirin, other items I have tossed. The Ministry of Health has offered him a data-entry position. He starts in a few weeks, for seven dollars a day. “It is not enough,” he says.

I make my bed, fold the bathroom towels. I leave no sign I slept here. I have some time before I head to the airport. Aziz says he will wait for me in the car; I’m to listen for his honk when it’s time to go. Inshallah, he says, nothing will happen today to delay my flight. “Do you feel lucky?” he says on his way out.

Last night, despite the blast, I had dinner with Mr. Gigolo, Mr. Nike, and Mr. Meat at our old stomping ground, the Herat Restaurant. Mr. Nike repairs bicycles. Mr. Meat sells CDs. Each earns six dollars a week, as does Mr. Gigolo. They told me that in 2004, shortly after I left, another foreigner had offered each of them one hundred dollars a month to support his family while he attended school. But like me, the man vanished. They never heard from him again, and they dropped out of Aschiana.

“I was happy in Aschiana,” Mr. Gigolo said to me; Aziz translated. “I can’t compare that time to now. I hope to have a good time in the future. I don’t know the future. I know just the day and the night, one after the other. I never think of what will be beyond.”

I weighed Mr. Gigolo’s words, wondering whether I could give him and the other boys a reason to envision their futures. I recalled the man’s offer and considered sending them each one hundred dollars a month, whether I could afford to do that on my salary. After a moment, I promised only that I would try. It would be a small gesture, but it would give me the chance fulfill an unspoken pledge I made to them more than three years ago.

I heft the duffel and leave my room. In the lobby, the man at the reception counter studies an English-language textbook. He attends Kabul University. He points to a word and asks me to pronounce it.

“City,” I say. “Ci—tee.”

“Ci … tee?”

“Yes.”

He points to another word.

“Bridge,” I say.

Outside, Aziz beeps. I glance at my watch.

“I have to go,” I tell him. “I’m leaving.”

“Yes,” he says. “I know.”