My first memory is of color. I am a year old. I stand up in my crib, clinging to the rails. I’m looking at a corner of my room. It is painted blue. Light, slightly greenish blue. There is nothing in the corner, only two walls meeting each other, but I see it and remember it.

I’m sitting at the dining room table in our old apartment on Maple Street. It’s a summer afternoon. I am just four years old. My mother is in the kitchen. The radio is on. I have a small stack of white typing paper in front of me. I have some crayons. I make a drawing. It is of two people, side by side. One is blue, the other is orange. The blue one is larger, and I draw a mark on his chest. My mother comes by and I show her the drawing.

It’s Superman, I tell her. And Robin.

Why do they have square heads? she asks me.

I puzzle over this. I realize that real people don’t have square heads. I realize that pictures can be something else—reality can go one way and the world in the picture can veer off into—well, I don’t know what, yet.

But I am going to do my best to find out.

In fourth grade I win a prize for a drawing. We don’t have regular art class, but occasionally we get to do something like art, usually to keep us busy and quiet on a rainy day when we cannot be decanted onto the playground during recess. For some reason the class is told to draw the TV character Fat Albert.

I don’t quite know who Fat Albert is (he is a cartoon character on a show created by Bill Cosby) but I have a notion of what he looks like (overweight, black, friendly). All the kids in my class are white. All the kids in the whole school, in fact, are white. We all sit there industriously drawing Fat Albert. The other kids draw him alone, hovering in space on manila paper. I draw him in a barnyard chasing a chicken and being chased by a blond white girl who looks like Elly on The Beverly Hillbillies. The chickens look alarmed. Fat Albert is holding a knife and fork. Fat Albert is hungry. He is going to catch the chicken and have her for dinner.

The substitute teacher looks over all our drawings and chooses mine. He explains to the class that my drawing is the best because I have told a story, the drawing is interesting because there are characters and we are curious about what will happen to them.

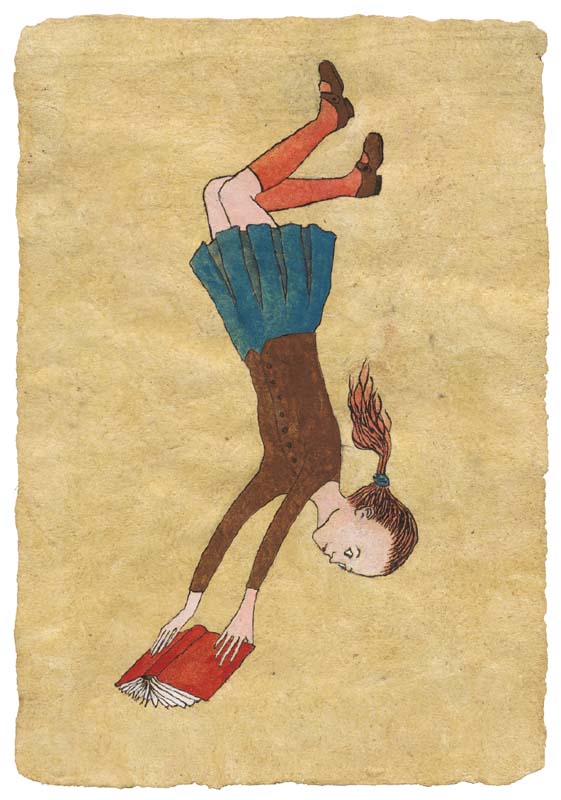

I always tried to tell stories with pictures, and this was the first time anyone told me that was unusual. To me it seemed like the most normal and absorbing thing in the world.

Years later, I am fourteen and have been attending high school for only a few weeks when I come down with an ear infection. This one is especially bad, and I spend a week on our couch, heating pad pressed to my horrible ear, reading. My mom kindly goes to the library and brings home a huge stack of art books. One of these is Brian Reade’s catalogue for the Victoria & Albert Museum’s Aubrey Beardsley exhibition. I fall in love.

It is not Beardsley himself I am in love with: He is beaky and gawky, tragic and tubercular. Even at fourteen I understand that he is one of Art’s Bad Boys, impudent, precocious, precious. The thing I love is his line. His work is almost Japanese in its minimalism, black and white, line and wash, ink and empty paper describing worlds. He is an illustrator, but he is not subservient to any text. I want this line and this freedom for myself. I begin to imitate Beardsley’s work. I don’t copy, but I make drawings with a dip pen; I work in his style. I have fallen out of my own time and into the 1890s.

So much of what forms us is accidental, ephemeral-seeming. When I was young I knew I wanted to be an artist. Sometimes I wanted to be a writer, too, and make books; sometimes I wanted to be a singer. For a brief period when I was twelve I wanted to be a jockey (and twelve was the last time in my life I would ever be small enough for that job). I wanted to be an artist because my mother, Patricia Tamandl Niffenegger, is an artist, and no one ever told me grown people don’t sit around making things all day. From the time I was very small I told stories and stories were told to me. Books were read to me, and I could see that books equaled worlds. Somewhere along the way I realized that the trick is never to stop. I understood intuitively that art (or what John Cage called “purposeless play”) was important in ways that had nothing to do with “what do you want to be when you grow up?” I knew there was probably no career in it. Art was a method of manifesting bits of myself and sending them off into the world to fend and make their own way. Art was a vocation.

In my application essay for art school I wrote that I wanted to be an Art Nun. I don’t know if anyone else at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in the early 1980s felt that way, but there was a dark intensity to the place that felt like home. Punk had blossomed into a spiky, nocturnal scene; Chicago felt more dangerous then. Being an Art Nun didn’t mean giving up sex. Sex has always been part of art, somehow, just like every other vital human experience. My friends at SAIC were often whimsical and absurd, but dead serious in their approach to making art. The thing I had in common with them was intensity. I often felt insufficiently Romantic around my friends. I was living at home in suburban safety (it was the only way we could afford such an expensive school). My purple hair was dyed at a salon. My parents gave me an allowance to buy art supplies. My friends were grittier and had more worrisome tastes than I did. But we were all determined to take this art thing as far as it would go.

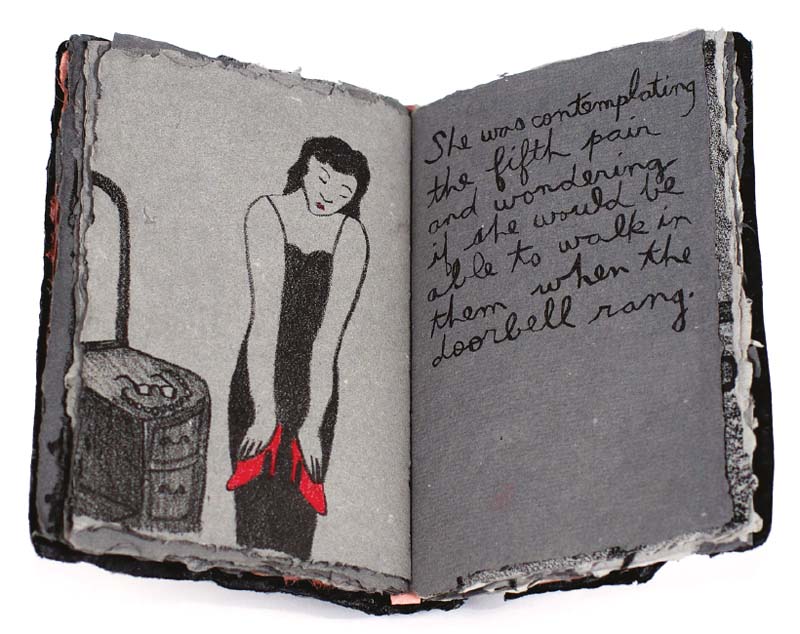

In the summer before my third year at SAIC I made a series of drawings of a woman who wore elbow-length gloves and a long skirt. Her breasts were exposed, but she seemed not to mind. She appeared unfazed in the drawings although she was transforming into a giant moth, giving birth to a cat, unraveling as though made of string. I could see that this was a story, though not a very linear one; it had dream logic, fairy-tale structure. It became The Adventuress. To make it I learned letterpress printing and hand bookbinding. Elsewhere on the planet personal computers had been invented, but their type was pixilated and they couldn’t handle handmade paper. So I acquired more 500-year-old skills.

After I graduated I became deeply involved in the book world, though not in the usual sense. I wanted to publish “normal” books, but my books didn’t fit any category in trade publishing. I received some interesting rejection letters (“this is brilliant but we can’t publish it”). So I happily continued to write, make prints, handset the words in lead type, and bind my books in small editions. I joined the Chicago Hand Bookbinders, a group that included book conservators and fine binders; I studied fine bookbinding and learned to work with leather and vellum and to repair books; along with another artist, Pamela Barrie, I established a letterpress studio, Green Window Printers. We happened to be forming our studio just as the last generation of commercial letterpress printers was retiring, so we often found ourselves buying type from old men who found the very existence of female printers a little disturbing.

In 1989 I went to graduate school at Northwestern University. At the time it was a haven for realists who wanted to draw, and it was a good place for someone who wanted to make narrative art. At the time I was working on my second large book, The Three Incestuous Sisters, and though I was the only printmaker and somewhat isolated, it was a formative period for me.

Chicago was a good place to be during the 1980s and 1990s if you were interested in the book arts, since the city had so many people making exciting books. A bunch of us got together in 1993 and began to create the organization that became the Columbia College Chicago Center for Book and Paper Arts. One of my many tasks was to write catalogue copy for our class brochures. This was very boring, and I started to make the class descriptions more and more outré. The weirder the brochures became, the more I got interested in writing. I began working on a novel, which became The Time Traveler’s Wife.

The idea for The Time Traveler’s Wife came to me while I was making a drawing. Drawing is a good thing to do when you are writing because the language-wielding part of the brain isn’t in use, so ideas drift along while you are looking and making marks. The idea was just the phrase: the time traveler’s wife. I wrote it down and began to think about it. Who was this wife? Why had she married a time traveler? That must be rather lonely… . The more questions I asked, the more the story evolved. Five years later I had written a 600-page manuscript.

Almost everything I have made falls outside the recent trends of art and literature. Chicago prizes outsiders and oddballs; I do too. But being outside of categories sometimes makes it more difficult to be exhibited or published. I have been lucky to have worked with one gallery for more than twenty-five years—Printworks Gallery in Chicago—-and I have also been blessed with brilliant collectors who don’t mind strangeness, who, in fact, really like the unusual. But when I approached the world of publishing, it took time to find people who were interested in the odd and uncategorizable. The Time Traveler’s Wife was saved from life in a drawer by Joseph Regal, who became my agent and found it a home in tiny MacAdam/Cage, an independent publisher in San Francisco. They were fine with quirkiness. The book became a bestseller, which was the strangest thing that has happened to me. The outer realms of art were very familiar and comfortable; to suddenly have millions of readers was unsettling. In the art world popular things are suspect, so it took me a while to adjust to the new scale of my audience.

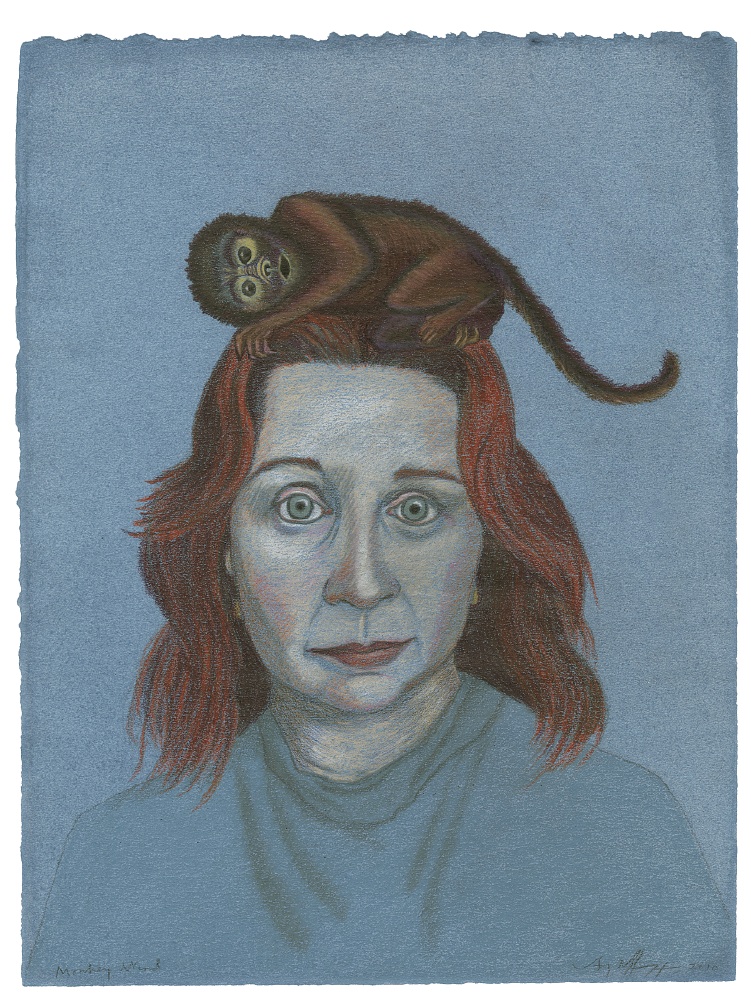

Since I was very young I have been making art about death and decay, the passing of time, the inevitability of change. It was an abstract idea for me in my teens, twenties, thirties, but now that I am about to turn fifty it feels like an old friend. The self-portrait was originally a means for me to examine loneliness, sadness, skepticism, fury, delight, dreams, all the uncomfortable mental furnishings I didn’t want to load onto to someone else in a portrait. It has become a record of my past emotions and thoughts, sometimes diaristic, sometimes fictional. My curiosity about death, love, the irrational, the fleeting nature of everything: It will never be satisfied. My work is not meant to comfort or pacify; it is always a question and the answer is always imminent, never arriving.

Art is not a science of emotion; there will be no incontrovertible results. But the mysteries still ask to be given forms, the stories I tell shape my thoughts. I am still on the same path I first took when I was a child, awake in the dream world, making and unmaking that world with black lines on pieces of paper, never knowing, always wondering.