February 2003

We drive out of Niamey, the capital of Niger, through a mishmash of taxis and trucks and camels and goats and endless streams of people walking. After about ten kilometers, we stop at a checkpoint and pay a toll. A sticker is affixed to our window to carry us through the next 800 kilometers with a minimum of hassle. From here to Agadez we will pass perhaps fifteen or twenty checkpoints that seem entirely random. Sometimes there are armed and uniformed people; sometimes it is just a group of men with a rope across the road hooked to two fifty-gallon drums. Sometimes money is palmed in a handshake from Moussa, our guide, to one of the guards and the rope is lowered and we drive on.

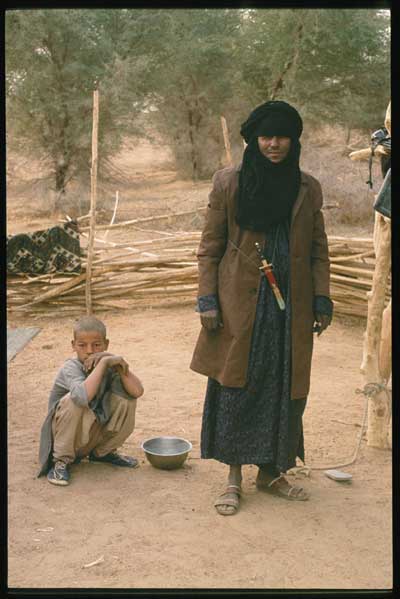

We are a group of five, led by Bess as she continues her work among the Tuareg who have roamed this land for centuries in a great arc from Tangiers to Cairo. Bess’s projects bring elementary education and AIDS awareness to this remote corner of the world. Until recently the Tuareg had no interest in AIDS education, no interest in education at all, but they have realized that the modern world, which is chasing them into a corner, will simply roll over them unless they learn how to read and write. And, while the Third World is used to people coming, bringing things, and then leaving, Bess asks that the Tuareg invest in themselves. If she supplies a pump for irrigation she demands they buy the gas by selling vegetables. If she brings medicine she insists that it is a starter supply. Bess is not interested in charity, her objective is social change. These are good works, to be sure but, truth be told, I’m just the photographer, the experience junkie. I’m along for the ride.

For fourteen hours from Niamey to Agadez, we bounce down a two-lane tar road. It is hot and dusty and tedious, and the road is dotted with livestock. The landscape reminds me of west Texas—flat sandy scrub, thorn trees, a small mesa rising up in the distance, rural villages with beehive-like granaries built on stilts, an old man sitting beside a pile of wood for sale as though his expectations were reasonable.

About halfway to Agadez, we pull into a gas station and discover the government has closed the southern border with Nigeria, so there is no fuel. We backtrack to the other end of town to purchase contraband diesel. It takes forty-five minutes. We are implored to buy jewelry, cigarettes, shoeshines, swords, white plastic kewpie dolls, grilled meat, wooden carvings, leather bags, more jewelry. I have made it myself. It is very good. You like? I make you a special price. I need food.

Close to 9 P.M. we stop for fuel again. This time they have diesel. It is on the outskirts of a nameless town, a raw gash of cement block and neon. The large, plate-glass window is a tableau, a theater of the peculiar, if not the absurd. It has all the accouterments of an American gas station—oil, wiper blades, cash register—and a young man bowing at his evening prayers, undeterred by white people milling about in his parking lot.

Finally, just after midnight, we arrive in Agadez and are obliged by custom and hospitality to share a large meal of meat, vegetables, couscous, and tea. Tea is a constant in Niger. A very sweet, cloying liquid, it seems to be made at every possible opportunity. If a truck breaks down beside the road, they make tea. If it doesn’t break down, they stop to make tea anyway. It is ubiquitous.

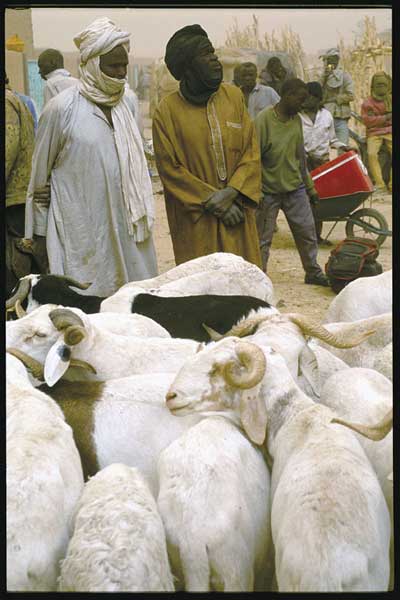

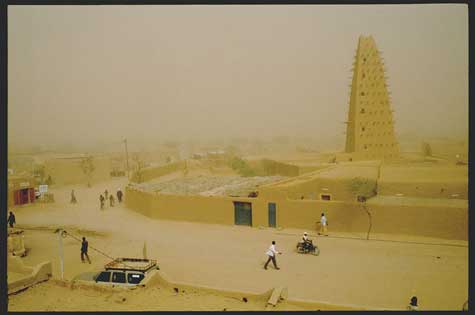

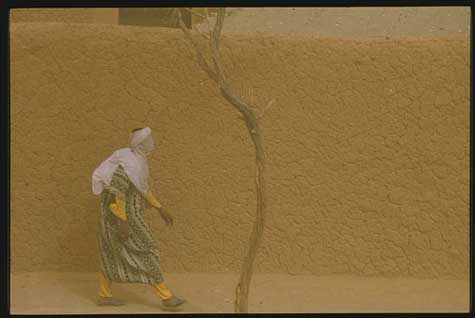

In the morning we awake to strong wind humming around the hotel and the clatter of loose things. Open the curtain and it’s unbelievable. Remove a couple of parked vehicles and we have been blown back into a nineteenth-century desertmarket town, the gale-force wind driving sand up into the sky. Tuareg men with ribbons of cloth trailing out behind them. Their faces are covered against the assault of wind as they drive squinting animals laden with hay and grain and wood. Women huddle in doorways, their forms revealed only by the colorful fabric pressed against their bodies. Dust devils filled with straw and plastic bags dance down the street and dissipate like apparitions.

We head further out into the nothing. On the outskirts of Agadez we pass slum encampments. A camel train wanders in the distance under high tension wires.

One hundred sixty-five kilometers from Agadez, we take a right off the road and will not see anything other than dirt tracks for six days. In places we can travel at seventy kilometers per hour, in others only three. This is where Bess does her work among the Tuareg. This part of our journey will take us another 450 kilometers, ending up at the great dunes of the Sahara.

It is a landscape that is impossible for me to read. We are heading for a specific destination and yet I cannot glean any information from all these thorn trees and bushes that would cause Labbo, our driver, to turn left here and then right there. Yes, there are vehicle tracks to follow, but they are everywhere crisscrossing in all directions, and yet in twenty minutes we arrive at the camp of Moussa’s extended family, a collection of eight or ten domed, mat-covered dwellings with fires and children and wandering goats and camels. It is clear in my mind that we have arrived at a place that is far more remote physically and culturally than any place I have ever been. It is as though Lewis and Clark had arrived at an Oglala encampment in a stretch limo.

We make camp in the waning light. The moon is already up. It will be full in three or four days. Houna, our cook, builds a fire and prepares supper. We scavenge for dead wood to build a second fire to sit around and relax in the cooling evening. We laugh and chat, eating our couscous stew and kicking a stick farther into the fire. There is no place to go other than here. There is nothing else to do other than this.

Soon, the poet arrives. A woman takes out a single stringed instrument and a bow and starts to play. The poet begins his chant—a lament about war and love Moussa tells us later. The sung poem goes on for half an hour, the bowed instrument’s notes rising and falling, and from time to time a woman ululates. Finally, the fire dies down and people wander off in the darkness to their encampment, their tents, their private lives. We go to our tent, listening to the zippers of other people’s tents opening and closing, listening to low incomprehensible conversations, listening to camels and goats foraging on the thorn trees and brush, listening to the earth breathe as a breeze scatters dry leaves along the ground.

The next morning we crowd into the adobe-walled school in Gougeram—the only permanent structure for a hundred kilometers or more. Teachers, parents, and students mill about. They have walked or ridden animals, as far as ten kilometers, but they are dressed in their best clothes for this important meeting. There is a variety of problems: mattresses have been stolen, the school’s pump has been commandeered, the drugs have been used but no money collected to replace them.

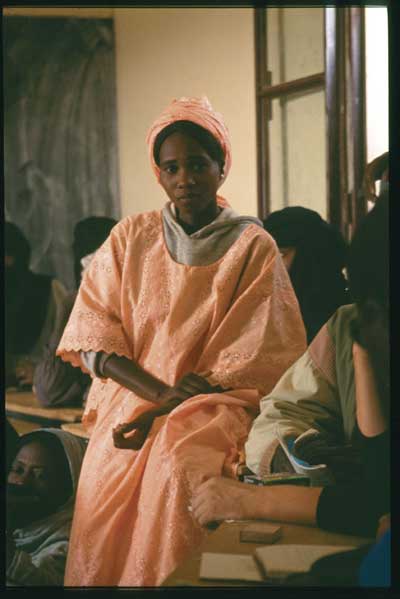

A handsome woman in an orange dress sits on a desk. A young boy sits backlit in a window. A woman in her twenties nurses a child. Older men in turbans confer. There is a great deal of back and forth in Tamashek, French, English. For over two hours, every detail is debated. Finally, Bess puts her foot down. The pump is for the school. Period. The pump waters the school’s garden, the vegetables grown and sold by the students pay for the gas to run the pump, and whatever is leftover goes to the school. That’s the deal. Take it or leave it. They take it. And all questions seem resolved.

In the morning, after coffee and biscuits and fruit, packing and repacking vehicles to make sure that what is needed is on top, we are off to the oasis at Iferoune, 160 kilometers away. On the way, we come upon a strange object next to the road—two vertical sticks about six feet tall with a shorter crossbar, wrapped in a frayed cloth and leather. It has the aura of a voodoo doll, especially out here where we haven’t seen a manmade object in two hours. Moussa says it is to scare off jackals. It’s hard to see why anyone would worry about jackals out here, but the Tuareg believe in djinns—mysterious and powerful presences.

By nine P.M., having been thoroughly shaken for seven hours, we arrive. We are here to meet with the local AIDS committee, which is responsible for education and condom sales throughout the region. After supper, we gather in a sparse, cinderblock building in the south of town. People sit on cushions on the floor, a beat-up couch with torn upholstery. A single, bare bulb hangs from the ceiling. In a corner of the room, a man in an old Naugahyde chair watches a black-and-white television, tuned to Al-Jazeera, its sound turned down. Jet fighters fly across the screen. Angry demonstrators set things on fire. Outraged orators raise their fists. It is the only time I have had an overwhelming sense that I am in a place that I ought not to be: south of Libya, west of Chad, among a warrior culture the Bush Administration has just falsely accused of conspiring with Iraq.

Tomorrow, we will drive into the heat of midmorning toward the dunes of the Sahara, entering into the limbo between things and no things. By no thing, I mean sand—enormous waves of sand, marching like a building sea, forced on relentlessly by the prevailing winds. This will be our reward for perseverance, for discomfort, for patience: to stand at the rim of a plateau as the afternoon landscape transforms itself from deep, undulating shadows into flat-lit dunes, shifting in the moonlight. I will walk down onto the dark valley floor, scrape my foot along the ground, and sit. Resounding silence. It is hard to decide whether to be frightened or comforted. Out here, at the very edge of nowhere, what is there to cling to?

Text and photos copyright Charter Weeks.