There is a stranger in the house. He sits on a sofa sipping coffee. He has pale white skin and blue eyes that take everything in—the lace-framed wedding photos, the half-dozen crucifixes, the mutt that watches from the corner, the enormous television playing cartoons for a young boy. Most of all, he takes in the man across from him.

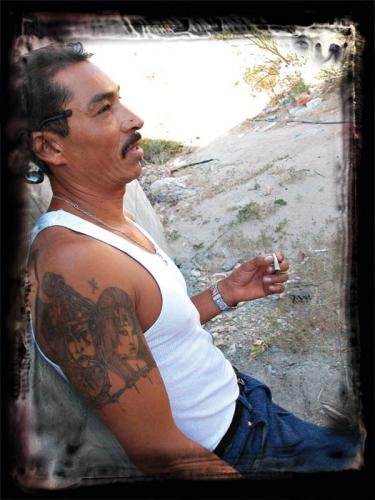

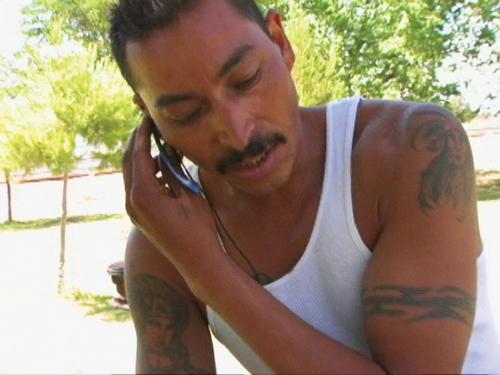

His host is thirty-four. Five-foot-seven, one hundred fifty pounds. He has a pair of ornate tattoos—a Virgin Mary coiled around one arm and an Aztec warrior wrapped around the other. “El mero mero,” people call him. Boss of the bosses. The real deal. Which is why the blue-eyed stranger has come, why he thinks that his host will take him across. Because in this place, this ugly desert on the far edge of Juárez, this man—Manny Carrizales Rios—is boss.

The stranger has come here through a middleman, an intermediary who probably in turn required his own middleman. That is how things are in this place. Nothing is simple—most of all getting what you actually want. He tells his host that he will pay five times the going rate to be crossed. Five times the normal price for it to be quick and safe and very secret. He is polite and serious. His Spanish is good. Still, there is a trace of something in his accent—something odd, something off.

“No problem,” Manny tells the stranger. “Everything can be arranged.”

The stranger stares back at him.

“If things go well,” he says, “I will bring you more people.”

Manny nods. Of course.

Manny’s mother, the old woman, limps into the room. She has cooked a lunch if the stranger will have it. Manny excuses himself. He needs to use the toilet, he says. The stranger nods, and an old woman beckons him into the simple, dirt-floored kitchen where she has laid out a meal of beans and rice and opened a bottle of Coca-Cola just for him.

Manny walks to the outhouse at the back of the property. He ducks behind it. Then he pulls a cell phone from his jeans and dials an American number.

Boss of the bosses. What a ridiculous thing to call him. What does that mean here? What does it get him? Cigarettes at the corner store? A beer perhaps? A cut of anyone’s take if he happens to find out about it. A bunch of fawning, unemployed teenagers who laugh at his jokes and do what he says. The neighborhood whores. A few old friends. What else? Nothing that lasts. Someday it will end. Someday his own people or someone else’s people will kill him. And that will be that. He knows this: unless something changes, he will die. And that’s what has driven him to make this call, to risk his life smuggling a supposed terrorist into the US.

He gets voicemail.

“Papí, es Manny. Papí, por favor me llames, eh. Es importante. Muy importante. Call me, Papí. Please. It’s Manny.”

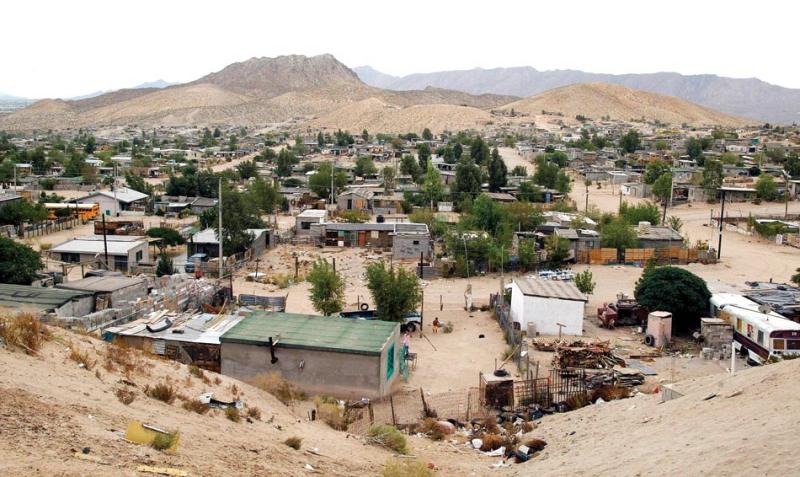

Manny’s mother lives in a rambling house of cinderblock and plywood. It sits atop a small hill less than fifty yards south of the US-Mexico border. They call this place Rancho Anapra—clapboard houses and dusty byways, piles of trash and hand-drawn shop signs. It sits at the western edge of Ciudad Juárez, separated from the city center by a mountain called Cristo Rey. Thirty years ago, migrants from Durango and Aguascalientes came north looking for anything they could find. El Norte wouldn’t take them. Juárez wouldn’t have them. So they turned to the desert west of the city. They built homes made of cardboard and stray timber. They carved a grid of dirt roads through the desert. They set down roots and sent word to family and friends that they had made their stake.

Juárez grew and grew, doubling, tripling, and quadrupling as word of new factories along the border spread south. A tide of new residents subsumed the city, and by 2002, that tide had swept up Anapra and made it an extension of Juárez itself. Rancho Anapra was no longer a rural outpost but a burgeoning, impoverished suburb. A town full of workers—“a nest full of rats,” as one Mexican police officer told me.

Manny’s people were some of the first to come here. Twenty-five years ago, their house was a lonely outpost overlooking the promised land. Today, it has a concrete living room floor, a chicken coop in back, a room where the old woman’s husband (Manny’s father) lives by himself, and an outhouse perched at the rear of the lot, seeping shit into the neighbor’s yard below. There are flower beds made of tires, a laundry line with clothes bobbing in the wind, a framed picture of the Virgin Mary on the front door, and a paneless window that they nail shut in the winter.

This is Manny’s kingdom. All its worth is found in the line of corrugated steel and fencing that begins just one hundred feet away. The border. Wealthy developers are trying to create a new port of entry here. “A gateway to New Mexico,” they promise. Puerto Anapra. But it already is a gateway. Most nights, smugglers and bandits bring drugs and migrants north and truckloads of untaxed goods—fayuca—south. And Manny’s home sits at the center of it all. Like a lighthouse in the dark.

For nearly one hundred and fifty years, businessmen on both sides of this line have transported goods back and forth across the divide. Today, that means car parts and electric appliances, automatic weapons and untaxed cigarettes, toilet seats and aluminum siding, kilos of cocaine and bales of marijuana. Goods flow north. Goods flow south. Sometimes they pass legally. Other times they do not. Somewhere along the way, regardless of their legality or means of entry, they transform into something else. Cash. The bills are stacked and counted, wired and shipped, only to be cut and sliced and reshuffled and redealt again, all so another round of middlemen can take their piece and pass it on once more. That is what this border is all about.

Manny hasn’t been able to reach Papí. So, now he rings another number. Mine. I am with my girlfriend. We are on a holiday tourbus, taking in Vancouver. And then, the phone rings. Manny’s number again. He has already rung twice. This time I answer.

“Bueno. ¿Que onda, Manny?”

Manny doesn’t wait for my question. He is already talking.

“Oyé, I don’t have any time,” he says. “You need to call Papí for me. I need you to keep calling Papí until he answers. You need to tell him I have a terrorist in my house right now. Right now. ¿Comprendes?”

I don’t know what to say.

“Al Qaeda is sitting in the kitchen with my mother right now. ¿Me entiendes?” Manny whispers. “Al Qaeda. Terroristas. I need you to tell Papí that this guy wants me to take him across tonight—tonight. You hear me? Tell Papí this guy has a bunch of others with him too.”

“What?” I say.

“I have to go. Call Papí.”

I ring the same number that Manny rang. I leave a message. Then, I call a few other numbers and leave messages there too. And finally, I reach this Papí. I explain everything. We hang up. Soon Manny calls back.

“Did you talk to him?” he asks.

“Yeah, he says they’ll make it happen. You bring the guy across. They pick him up, and then you go free.”

“No. I bring him across. I deliver him to the motel. I leave. Then, they take him. If they do it sooner, everyone will know what happened.”

“Okay, okay. Let me call him back.”

“And if I cross him, they promise not to arrest me, right?”

“That’s what he says.”

“Okay,” Manny says, and he hangs up.

Trace this story to its start. You’ll find a twenty-seven-year-old migrant smuggler about to be sentenced to five years hard time in an American penitentiary.

There are predators and prey in prison. Manny was determined not to be prey. He joined a prison gang. The Border Brothers. In San Antonio, he stabbed a rival gang leader to death with a pencil during a prison riot. The authorities transferred him to a facility in Louisiana, where he then beat a man nearly to death with a bar of soap dropped in a sock. Each brutal act only strengthened Manny’s reputation.

In five years, he made a name for himself. He made friends. Developed connections. And in 2001, when it came time for his release, Manny had a reputation, a criminal family, and a rank. He was a captain now. With gang tattoos and a backstory that preceded him. When US Marshals flew him to El Paso and unshackled him at the Free Bridge leading into Juárez, they were turning Manny loose on a city of opportunities.

Street gangs have subdivided most all of Juárez. As in any city, the gangs are part neighborhood protector, part neighborhood predator. They feed on what they can find, dealing drugs, preying on outsiders, and leasing themselves out to anyone with a problem that needs solving. They are entrepreneurs of a sort, family of a kind, criminals to be sure, and they do what it takes to survive.

Anapra’s street gangs are no different. Gang members here call themselves soldiers. Siete Dos has forty or fifty of them. Boys really. A few as young as ten. Two dozen or so past the age of twenty. Some have day jobs. Some do not. Some are criminals. Others are just civilians with an attitude. In the evenings, they drink beer and play soccer in the streets. They whistle at girls and bust each other’s chops. Most street gangs deal, steal, and hustle. Nothing more. Their view of the world is ground-level. But Siete Dos is a little different. Siete Dos controls a mile-long stretch of the US-Mexico border. And that mile-long stretch connects the gang to a host of far more powerful players in Juárez’s underground economy.

Manny returned from prison with not so much a plan as an intention. He knew what he was capable of, and he knew how to get it. Taking over Siete Dos was almost effortless. No need for violence. No killing. Everyone knew better than to cross Manny. They knew the crown was his if he wanted it. Soon, under Manny’s hand, the gang was smuggling loads of untaxed electronics south and a mix of drugs and migrants north. And on the nights it wasn’t smuggling, Siete Dos was robbing freight trains.

On any given day, forty to sixty Union Pacific trains lumbered east from ports on the Pacific, loaded with goods from Asian freighters—textiles and automobiles, coal and timber, dishwashers and microwaves. Over the course of four or five days, the trains would trudge east, offloading product. It was a mostly uneventful journey, but every engineer knew that along the two-mile stretch of track running past Anapra, most anything could and likely would happen.

There are many ways to rob a freight train. You can cut a brake line or hold a hostage. You can block the tracks or bribe a guard. You can hop and ride for hundreds of miles tossing freight off the side. The preferred method in Anapra was a pair of jumper cables and a spare car battery. Run the cables to the track. Trip the train’s emergency braking system. Then swarm it and take whatever you can.

Surveillance footage tells the story. Forty, sixty, seventy men pouncing on the cars, busting the padlocks, breaking the in-bond seals. In a matter of five or six minutes, they haul away three dozen washing machines, a hundred television sets. It seems the whole neighborhood is watching. Little kids cheer as the appliances are shuttled back to waiting trucks.

Do that three or four times a week, and you have quite the enterprise. No one is going to stop you. It would take a hundred police officers to protect these trains—a hundred honest, law-and-order types with guns and body armor, but there aren’t any cops like that here.

See for yourself. Look at the tapes the US Border Patrol keeps. There they are, standing near Manny’s house—a group of Juárez police officers—joking around while Siete Dos gang members load appliances into the back of their police camper. One of the cops looks toward the security camera and flips the bird. Everyone chuckles.

And that’s how it works. That’s the real order of things in Juárez.

They call it “The Juarez Cartel.” People say it runs this city, that no one does business here without its permission. How it truly functions is open to debate, but the cartel’s power is real. It manages a kind of franchise system, granting vendors a license to engage in certain activities in exchange for a cut of their take.

For years, no self-respecting criminal robbed, cheated, or smuggled without the cartel’s permission. And permission was only the beginning. Payments followed. Payments to the cartel. Payments to the cops. Payments to the mayors and the judges. Then and only then did you have any assurance that you wouldn’t be arrested, that nobody was going to find your body stuffed in a garbage can with a message carved into your forehead.

Every month, Manny visited the esteemed offices of Chihuahua’s State Police and delivered a cut of his gang’s earnings to a state comandante. He did the same with the municipal police and the feds whenever they came looking. In return, Siete Dos was allowed to do with their territory as they saw fit. This was the order of things in this city. Siete Dos paid for the right to their turf, and they paid for the right to do whatever it took to protect it.

Once, two migrants from Aguascalientes came north and took shelter in Anapra for a few days, hoping to cross. Everyone knew they were here. They rented a room a few hundred yards south of the fence line. Somebody told them about Manny’s mountain, about the arroyos that snake along its base. The two men decided to cross that way. A teen boy offered to take them for 1,500 pesos. Maybe they didn’t know it was Manny’s mountain. Maybe they didn’t realize the offer wasn’t optional. They turned the boy down. They would cross on their own. So, the boy left. The men waited until night. Then, they set out, moving quietly from one rocky outcrop to the next. Suddenly, a man appeared from the darkness. He had a club in his hand, a bat. He beat the two migrants, one of them to death.

It wasn’t personal. It wasn’t something Manny wanted to do—or did not want to do. It was simply required of his position. No one was surprised. No one was really troubled. There’s an order to things. Honor it and you live. Disrespect it and you die. Manny had the boy dig a hole on the mountaintop and bury the dead migrant.

In the evenings, when the heat lifted and there was music coming from someone’s car and men out in the yard drinking beer and kids playing soccer in the dusty street, Manny would sit on his ramshackle porch, smoking cigarettes, watching the falling sun, waiting for the darkness.

And that’s where he was on this particular night—watching a Union Pacific train roll down the track and past his house. Three, maybe four million pounds of steel and coal and copper drifting across the desert on its way to a Midwest car lot or an East Coast Wal-Mart or anywhere in between. Manny took a drag on his cigarette, held back the smoke and waited. His eyes narrowed. The sound of that train, the squeal of steel on steel, the want in his eyes. He parted his lips and let the smoke billow into the darkness.

“Ya,” he said.

Manny grabbed an old JanSport school bag, got up, and walked to the back of his mother’s house, to a plywood and cardboard add-on room. Light and the sound of a soccer match came from inside. Manny entered and sat in a plastic chair alongside three men splayed out on mattresses in the dirt. Each had a plastic bag with a change of clothes, a few papers, and some water. This was all they would bring to the other side.

Manny didn’t speak for a long while. No one did. They just sat watching soccer, smoking. Finally, he got up and turned to leave.

“Banana is going to come and get you,” he told them. “Get your stuff ready.”

Tonight, members of Siete Dos would short circuit the Union Pacific brakes in hopes of stopping a freight train long enough to load three migrants on a grainer or into a container and send them on their way. All this effort for just $100 a head. It hardly seemed worth it, but work had dried up of late.

Siete Dos had made a terrible mistake nearly six months earlier, a mistake that had brought all of the gang’s business to a halt. They’d been hitting the Union Pacific line two or three times a week, making good money. Manny had tried to warn his boys off. “We don’t want to draw too much attention,” he’d told them. But he couldn’t always be there, and in recent months there were some members who did as they pleased. So, the robberies continued, until one night, some Siete Dos boys hit a train that had an FBI SWAT team hidden aboard. When the dust settled, a dozen Mexican nationals were in custody and two FBI agents had been bludgeoned nearly to death.

It’s one thing to rob, steal, and smuggle, to bully your own kind and murder your enemies, quite another to embarrass the gringos, to humiliate them so publicly. The FBI wanted revenge. Manny was sure they were hunting him too. The newspapers said so. Neighbors confirmed it. Even the local police were getting in on the act.

Weeks earlier, Mexican cops had grabbed Manny’s right-hand-man Lalo, tossed him in a car trunk, and driven him out to the middle of the desert. They told Lalo that the protection money the gang had been paying wasn’t cutting it anymore. Siete Dos was now more trouble than it was worth. One of the cops called over to El Paso and tried to negotiate a price for handing the gang lieutenant over, but the Americans wouldn’t dole out a reward to law enforcement agents. Hell, they couldn’t take him anyhow—not without legal extradition. Lalo could hear the cops discuss shooting him instead. They opened the trunk, slapped him around, and set him loose with one final message: you better make things right or you better disappear.

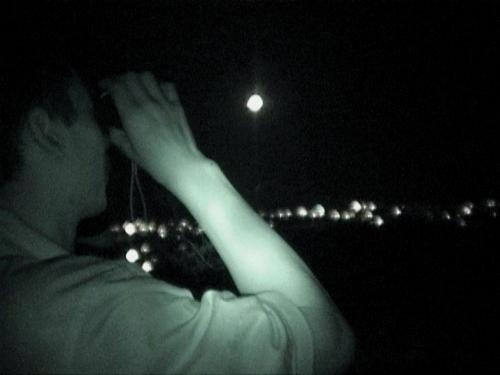

The thing is you can only lie low for so long. Eventually, you have to go back to work. At nine o’clock that evening, Manny reappeared in the doorway of the makeshift room. Plans had changed. The boy they called Banana had gone to buy a car battery. Manny would escort the three migrants himself. They grabbed their belongings. Manny led them onto the mountain, where they sat for two hours watching a pair of Border Patrol vehicles circle a patch of desert.

Some two or three miles away, a FLIR camera was posted on a mesa. The camera extended from the roof of a vehicle and craned out over the desert. This was the Border Patrol’s eye in the dark. It could see the heat Manny’s body gave off. At close enough range, it could pick up the details of a man’s face, his hair, his wrinkles, his lips, the cigarettes he smoked. Tonight, the agents knew Manny was here, and he knew they knew. It didn’t matter. Chase him too far and they’d risk another smuggler crossing. All they could do was wait.

One of the Border Patrol vehicles set out alongside the railroad track, the beams from its headlights bouncing up and down as it went. Then suddenly, the car vanished. Manny chuckled.

“Pinche fucking migra,” he said.

The agent had killed his headlights and gone off-road, hoping to disappear and then reappear somewhere else and catch Manny by surprise. Manny scanned the desert with his binoculars. And waited.

Finally, the vehicle reappeared several hundred meters closer, parked in an access tunnel that ran beneath the railroad track. In the distance, a long, serpentine freight train was rumbling eastward. In fifteen minutes that train would pass just thirty yards from where Manny and the migrants waited. Manny turned to the boy called Banana.

“Send them out,” he ordered. Banana whistled, and a few seconds later, there was a whistle in reply. Then, farther away, another whistle. The whistles moved down the line, until they reached the Anapra fenceline almost a mile away. Bright floodlights illuminated everything there, and you could see two figures toss a pair of backpacks through a hole in the fence and then wiggle their way through it. The decoys sprinted toward one of the access tunnels beneath the rail line. Two Border Patrol vehicles reacted immediately. The agent closest to Manny executed a three-point turn in the tunnel, flipped off his headlights, and gunned his vehicle through the desert. His brake lights flickered on and off, up and down, as he crested hills and hurdled bumps. The other Border Patrol vehicle raced to meet him.

“Send the next ones,” Manny told Banana. Banana whistled again. Almost immediately, one of the Border Patrol vehicles stopped. The car reversed, turned toward the fence, and ran its high beams along a stretch of dirt between the rails and the border. The light caught the bobbing head of someone sprinting.

Manny’s train was drawing near. It had turned a corner three miles in the distance at Anapra’s far end. One of the Border Patrol agents was now out of his vehicle, running alongside the rail line with a powerful torchlight in his hand. Manny watched until the agent disappeared below a ridge.

“Bueno,” whispered Manny. “Go with Banana.” Banana was already up and ready. He motioned the three migrants to follow. They turned for one more confirmation from Manny, but Manny was gone.

“We don’t have a lot of time,” Banana said. He set off down the canyon. The migrants scrambled after him. The freight train closing in—the steady clamor of a thousand wheels pounding the rail.

Banana took the migrants to a wall forty feet shy of the rail line. The four men were now one hundred yards into US territory and so far they had managed to stay out of sight. Beyond this wall, however, everything was exposed. So they waited for the train. The men heard the curdling squeal of wheels grinding against track. The train was braking. Not the soft braking that usually marks this curve either. The wheels were locked, desperately trying to bring millions of pounds of steel to a halt. The migrants ducked their heads as the engine came past them.

“Now!” said Banana. “Go on, go on.” The three migrants scrambled up the wall and raced across an open field toward the tracks. Manny was there waiting for them, just a few feet from the moving train. The train wheels spit sparks and shrieked. He was crouched like some kind of cat, and his head swiveled with every car that passed. He was counting, his pointer finger following each passing car.

The migrants were terrified. The train had slowed, but it hadn’t stopped.

“Right now! Get on that fucking train!” Manny was screaming. “Come on, pussy motherfucking Mexicans!”

Manny crouched and then executed a standing leap. His arms and legs clamped to the side of a passing freight container and the train whisked him down the line away from his clients and into the darkness.

But no one followed. No one dared. And in the seconds that followed Manny’s sudden departure, the consequences of their fear became apparent. A Border Patrol vehicle was racing towards them. The vehicle was still a half-mile out, but the dust trail it kicked up showed just how fast it was moving. Worse still, another vehicle waited, idling on the other side of the track, its headlights visible between the containers sweeping by.

The migrants took off running. One chased the train. Another ducked into the ravine. The third stumbled backward and then started jogging toward the mountain. They had missed their chance.

Manny had failed. There were no more migrants to cross, no trains to rob, no drugs to smuggle. Siete Dos had feasted for over a year, but now there was nothing. Not for Manny. Not for anyone. The gang was in tatters. Every man for himself. It was a rainy day. Manny sat in the back of my car smoking hand-rolled cigarettes. We had pulled to the side of Anapra’s main drag, and he had cracked a back window open. Rain pattered on the windshield.

“I want you to do something for me,” he said.

“What’s that?”

“I want to work for the FBI.”

“The Americans? How do you plan to do that?”

“You’re going to introduce me.”

I turned around in my seat. Two Siete Dos kids walked past the car and nodded at Manny. I watched them as they stopped and lingered, trying to get Manny’s attention.“Don’t worry about them,” he muttered. “They’re clowns. They can’t hear us anyway.”

We sat there in silence for a bit.

“Manny, you should know that working as an informant doesn’t usually end well.”

He nodded.

“The Americans don’t give a shit what happens to you. And neither will anybody else. They may promise to pay you and then never do it; they could trick you into something and then arrest you; they may blow your cover. You may be killed. It’s not all that different than the people you work with now.”

Manny sucked in another long drag of his cigarette and tapped the ash on the car window’s edge.

“Yo sé, yo sé,” he said, but he was impatient. “Look at me. I’m thirty-four. I have a baby boy. Do you know what that means? Pampers, lots of fucking Pampers.”

Manny chuckled at his own joke.

“Who’s going to pay for the Pampers, for the formula? I have the police after me. I have people in the neighborhood who think they can be the boss. And you know it’s getting worse.“

“What do you want out of this?”

“I want to help my community. “

I laughed. “You’re kidding, right?”

“No, en serio. I want to make this a better place. I can help the FBI get the people they want.”

I stared at him.

This was a man who had killed. Here he was talking like some kind of community organizer. And yet, I couldn’t help believing that there was a touch of truth to what he said. That’s the dark magic of Juárez—all these people who could be something else if only the city were other than what it is.

“But what do you want?” I asked.

“I want them to stop chasing me.”

“That’s it?”

“And pay me. So, I can move my family somewhere else.”

He talked about how a man couldn’t trust his own neighbors, how there was no common decency left, no honor among thieves. Gangsters had started robbing their own people. Cops were hopelessly corrupt. It was a city of nothing but addicts and cutthroats. The Americans were after him, the Mexican police were ready to hang him out to dry, his own gang was growing restless, his kids were going hungry—Manny was ready to snitch.

He wanted me to arrange a meeting. I refused.

“Then I’ll do it without you.”

“Manny, they don’t want to work with you. They want to put you in prison.”

He grinned a cocky, fuck-all sort of grin.

“It’s okay,” he said in English, turning on a cartoonish accent. “No problem.”

There’s an old brick factory down by the Rio Grande, and in the spring the river swells enough that kids come and swim. The brick factory has its own border crossing—now defunct—a road that joins the US and the Mexican sides. The road is surrounded by fencing and concertina, and a US Border Patrol agent spends all day parked in an SUV beneath a sunshade at the far end. Near the brick factory, there is a simple concrete post. Agents call it “Monument 1.” The post marks the precise location where Mexico and the United States meet. There is no fence here, and that’s why it was chosen as the location for a first meet between Manny and his would-be handler, “Papí.”

There are many ways for an informant to die. A slip of the tongue, a chance run-in, a strange coincidence, an intercepted phone call. Still, most informants die because the agents who run them just don’t care. They run sloppy surveillance. They make premature arrests. They don’t answer their phones. They promise things they can’t deliver. Or they just fuck them on purpose. I’ve seen all these things happen. In law enforcement circles, an informant is an asset. Not a person. Agents refer to them by number. They use the asset the way they’d use any tool. And when the asset has outlived its usefulness, they toss it.

I tried to explain this to Manny. I tried to tell him he was turning his life over to a barely functioning bureaucracy—a bureaucracy that didn’t give a damn about him. Getting killed was only the worst of it. Set that aside for a moment and ponder all the other crap: the reward money that never comes through, the immigration visas that are always “in process,” the missed meetings, the squandered opportunities, the operational restrictions, the countless times a person calls with information and gets no answer.

This was the world Manny was volunteering for. It seemed like madness to me. And yet, after months of refusing, I made a deal with him: in exchange for making an introduction, I would get to see his story—the story of a gangster-turned-informant—all the way through. So, I called the only cop I thought would treat him fairly.

It took several weeks to arrange the meeting. Manny worried about a trap, that the feds would simply arrest him. His would-be handler feared another Siete Dos ambush. In the end, they settled for Monument 1. The feds would never be able to mount an operation there in daylight and Manny’s people would be hard-pressed to pull anything either. Plus, there was me—the pale-skinned gabacho. I’d be there to broker it all.

Manny sat in the backseat smoking as we made our way there. I asked if he was still worried this might be some kind of trap.

“If this is a trap,” Manny said, “we’re all going to die together.”

He said it cooly, as if he were comfortable with the possibility.

“I’m not going easy,” he added. “I’m going to take some of those fuckers with me.”

We parked next to the river and waited by a statue of Benito Juárez.

Kids were playing in the water. A woman watched from the shore. Manny sat at the foot of the statue smoking. Across the river, a Border Patrol vehicle was parked in its customary spot. No sign of the feds. Then, a dark SUV appeared on the American side. We watched as it turned off the main road, crossed the river, and parked in a gravel cul-de-sac just a dozen yards away. Manny tossed his cigarette and stood up. The SUV’s passenger-side window rolled down, and a man wearing sunglasses waved. My phone rang.

“Tell him to come over to the car. We’re gonna talk in private.”

Manny looked at me. I nodded and forced a smile. Then, he trotted over to the car and disappeared into it. Thirty minutes later, the door opened again and out hopped Manny. The car rolled away.

“So?” I asked as he approached.

“Está bien.”

Manny pulled out another cigarette. He was smiling like a kid with a secret.

“Come on. Let’s go,” he said.

“What did he say?”

“Lots of things. Está bien, este Papí.”

It’s five in the afternoon, and I’m caught up in a cross-border game of telephone—Manny says, I say, Papí says, I say. It goes around and around. They’re trying to catch a terrorist—the most important mission that federal law enforcement could have—and they’re running the whole operation through a vacationing journalist.

Despite what Hollywood would have you believe, federal law enforcement agencies are profoundly bureaucratic. The wheels of justice turn slowly even on a weekday. On Saturday and Sunday they hardly turn at all. Still, terrorists have a way of getting everyone’s attention, so, Papí has managed to round up a couple dozen federal agents. Now, he’s on the phone in hopes that I can relay directions to Manny.

“Dude, Manny had better be right about this.”

“You should be having that conversation with him, Papí. Not me.”

“You gotta tell him. Tell him he’s got to be absolutely fucking sure that this is what he says it is.”

“All I can do is tell you what he said.”

“Yeah, well, he’s gonna be a rockstar if he’s right, but I’m fucking—” He gathers himself. “I’m gonna have some angry people on this side if he’s wrong. I just pulled like a dozen guys out of a DEA party. They were not happy.”

The situation is comical. Manny has been trying to call Papí all day long. They’ve spoken twice—enough for the two of them to agree on the basics of the sting, but now Manny has run out of call time on his throwaway cell phone. And Papí can’t make calls to Mexico. Which means the feds and their informant are reduced to relaying messages to one another via a third party: me.

“You know, he’s trying to do the right thing by you guys.”

“I know, I know. Manny’s got it coming. But if this goes down like he says, he’s gonna get it big time. He’s gonna be a fucking rock star.”

Papí had been saying that for years now. But rock stardom always seemed to be just around the bend. In the last two years, Manny had met with numerous agents. He’d answered questions, given information, and done what was asked of him. It hadn’t really gotten him anywhere. There were the occasional payments. Nothing big. Just enough to keep him in the game.

“Fuck them,” Manny told me.

“The system’s a mess,” Papí would say. He sympathized, but there wasn’t anything to do about it.

Manny’s last call came that evening. Actually, it wasn’t him at all. It was his Mother, Abuelita. Manny had simply asked her to call and tell me that he was going to the mountain. I relayed the message on to Papí.

“Fucked,” Papí tells me when I finally reach him the next afternoon. “This whole thing is fucked.”

He is angry. Manny’s stranger was no Arab terrorist. He was a Mexican. Or maybe a Colombian. Or maybe a Central American. Who fucking knows? But he wasn’t a goddamned Arab.

“This is bad. This is really bad. I mean he’s really fucked himself. Dude, it’s a shitstorm,” Papí says over and over. The feds have been inconvenienced. The US Border Patrol agents rousted from their weekend slumber are pissed. Manny sold them a terrorist, and all they got was a migrant of indeterminate Latin origin. The Border Patrol is ready to throw the book at Manny. He had crossed illegally. He’d smuggled someone into the country. He had no formal authorization to do that. Never mind all the past successes, all the quick hits—five hundred pounds of marijuana here, a load of migrants there. Manny had promised a big win and had failed to deliver.

“You know what, your dude is royally screwed. I mean you have no idea how bad—they’re ready to just lock him up and throw away the key.”

“Papí, I don’t know what’s going on over there, but you realize this guy was trying to do the right thing.”

“You don’t have to tell me.”

“So, for them to turn around and punish him for taking a risk, that’s—”

“Dude, I get it. You don’t have to tell me. This is, this is just a big fucking mess right now. It’s—I don’t know when he’s gonna get out. I’m trying, but this thing is bad. I mean I’ve got a lot of angry people. This is embarrassing.”

Papí made a promise to Manny, and he intends to keep it. It takes another week, but he manages to corner a federal prosecutor and plead Manny’s case. The informant had meant well. He thought he had a bona fide terrorist. Then we threaten to send him to prison for the rest of his life? What signal does that send?

The prosecutor nods. He gets it. There will be no prosecution. The case will be dropped. Still, it takes another two weeks before prison authorities set Manny free—two weeks too late as far as Manny is concerned. They had a deal. The Americans didn’t honor it. Manny had put everything on the line for them, but when things didn’t work out, they had turned on him.

“Fucking fuckers,” he says.

I ask Manny about the stranger, about the man he called a terrorist, the one Papí swears is probably just a funny talking Mexican.

“That wasn’t a Mexican,” Manny swears to me. “He was foreign.”

“You said he was a terrorist.”

“I said he was from Colombia.”

“You said he told you he was from Colombia, but that his accent was strange, that he sounded like he was from the Middle East.”

“Maybe so,” Manny concedes. “ Maybe he was FARC. Guerrilla. Those are terrorists.”

The story is changing. I don’t know what to say.

Manny shrugs and turns his eyes away. I ask if he’ll keep working with the Americans.

“Oh fuck the motherfuckers. Pinches pendejos.”

“Really?”

“What have they ever done for me?”

Sharp criminals know how the game works. If you feed investigators a reliable diet of actionable intelligence about competing organizations—information that investigators can use to build cases—you’ll keep the heat off yourself while simultaneously doing in your competition.

I can’t say whether it’s been his intention all along, but after the stranger, after his arrest and subsequent three-week incarceration, Manny begins to use American law enforcement for his own purposes. His calls are now infrequent, but when they do come they are invariably about gang movements in neighboring territory, loads to be crossed in Santa Teresa, the sudden appearance of Salvatrucha or 18th Street gangsters. It’s good information, but it’s also very clear what Manny is doing.

Sharp cops triangulate. They develop sources in different locations and organizations, and then they plot out the truth by referencing the coordinates of all the half-truths and patent lies people have given them.

“He thinks I don’t fucking know what it is he’s up to over there,” Papí tells me one morning over breakfast. “Manny tries to blame that shit on his brother or one of those other guys—oh, they did this, they told me that. It’s bullshit. I know he was right there with them.”

Manny has started drinking. In the bars, he brags about his power, about how he’s conned the FBI into working for him, how he has wrapped them around his finger, about the gringo journalist he’s using to communicate with contacts in the US. The more he drinks, the bigger the lies become, the more the stories grow, the more secrets he spills. Late at night, he stumbles home with a 9 mm pistol tucked into his waistband. Sometimes, he fires rounds off in the air.

I’ve been waiting nearly five years for this moment. It’s March 2008, and I’m on my way to Juárez one last time. Manny’s out, he tells me. Gone straight. No more crimes, no more feds. To prove it, he’s invited me to film him laying rebar and pouring concrete. He looks good—sober even. He holds his son and shows me pictures of his grandchild. Manny is thirty-nine. I ask him what’s come of the neighborhood? Manny’s brother El Chato is now in charge here. Everyone knows what a bastard El Chato is. The man makes Manny look like some kind of human rights activist.

“How’s El Chato?” I ask. “You two getting along?”

“Of course, we are. He’s fine.”

The old order is fading. Last summer, armed men temporarily occupied the whole of Anapra. They were Sinaloan foot soldiers—part of an ongoing struggle for control of the city. They held El Chato hostage for nearly a week while Manny hid out in the neighboring state of Durango. In the end, the gunmen were forced to retreat, but they still have some sway here in Anapra.

Today, we wander from barrio to barrio, chatting up vendors, mixing with street gangs. Wherever we go Manny has friends. Teenage gangsters most of them. Cholos. They crowd around with their gangster clothes, their knock-off brands, bumming cigarettes, vying for attention. It’s clear that, clean or not, Manny still wields a curious power here. They’re not even Siete Dos. Some are sworn enemies of Siete Dos. It doesn’t seem to matter. Toward midday, Manny takes me to Wonder-15 territory on the south side of Anapra. If there is anywhere in Anapra that we shouldn’t be, this is it.

Manny approaches a large group of Wonder-15 boys he knows. They are laughing—happy to see him. We start to chat. Everyone’s eager to chime in. Then, all of a sudden, Manny grabs me by the shoulder and yanks me away. His face has changed.

“Go stand by the car for a minute,” he says.

Manny walks back. There are two or three cholos inhaling agua crystal—a mix of paint thinner and other assorted poisons. One of them wears a gangster-style hairnet, his eyes cruel and empty. He’s pointing at Manny. Something about “Las Aztecas.” Manny whips his sunglasses off. The cholo backs up. “That’s right,” Manny says. “Get out of here you little faggot, before I fuck you.” The three of them scamper away like kicked dogs.

As soon as they’re gone, Manny pulls out a cell phone.

A few minutes later, a young man built like a bull terrier jumps out of a car. He’s short and squat and he has scars on his neck. He shakes Manny’s hand and pulls him aside. A minute later, the bull terrier walks over to all the remaining little gangsters and tells them to scram. Then, he turns to me.

“Who the hell are you?”

“That’s Jordan, the reporter,” says Manny.

The bull terrier sucks on his cigarette and stares at me. I can tell he’s trying to make sense of what a gringo is doing here.

“He’s cool,” Manny says.

The bull terrier nods. He hugs Manny. Then, he wraps his arm around me.

“This fucker’s like my older brother,” he says, pointing at Manny. “Did you know that?”

The bull terrier’s name is Noe. Manny has been sleeping with his mother, La Chicharron, on and off for almost two decades. Fresh out of prison, Noe is a captain, a shot-caller for Los Mejicles, a prison gang. On the south side of Anapra, Los Mejicles run everything—the drugs, the guns, the gangs. Everything.

Noe grabs me by the shoulder and orders me to get in his car.

We go to a barbecue that afternoon. Noe’s friends roll cars into the intersections to block traffic, set up a couple of makeshift soccer goals and turn on music. Off come the shirts, and the games begin.

Men in fancy trucks with tinted windows park in back and watch from a distance. They have their own separate meal. They look over at me occasionally. I nod, but there is no response.

Manny trots back and forth between the games in front and the heavy hitters in back. Every time I look over he is drinking and laughing. The party is like some kind of truce. I see types from all over —people who would never share drinks and play games under different circumstances.

Manny and Noe have their arms around each other, drunk. It’s near five o’clock. I’m not in the habit of staying in Anapra after dark. I tell Manny and Noe that I need to head out. They howl regrets, then Noe grabs me by the arm and tells me I should give them a ride home too.

“Noe’s got something he wants to talk with you about,” says Manny.

“Manny, why don’t you come over to my place?” says Noe. “We can all grab a beer.”

“Hell fucking no, motherfucker,” Manny slurs. “Your fucking Mejicles might be there.”

Noe clicks his teeth. “They won’t be there,” he says.

I drive toward Manny’s house. As we enter Siete Dos territory, Noe rolls up his window and slumps low in his seat. Manny starts laughing.

“Oh, you’re scared too?” he says.

We stop outside Manny’s one-room house. He is drunk. He gets out of the car and then spins around and shoves his head through the passenger side window. “Ask Noe how he got all those scars,” he says. Manny looks at Noe, shakes his head, and then pulls away. We watch as he stumbles to the door. “See you tomorrow, you bastards!” he calls out.

Noe and I leave the neighborhood in silence. He seems sullen. We drive slowly past a police vehicle parked on the side of the dirt road. The sun has already set. It’s dark. I watch the police vehicle in my rearview mirror. Noe tells me that he lives in a plywood shack behind his mother’s house. He wants to show me. He has some things to discuss. Important things. He’s drunk and I don’t want to offend him.

Inside, there’s a mattress on the floor, a small refrigerator in the corner, a television and a coffee pot, all of them plugged into one surge protector. Noe waves his hand.

“How do you like my place?”

“Looks nice,” I say.

“Bullshit. You know what this is? This is a fucking piece of shit. Tell the truth. I live in a shithole, right?”

“Well, I don’t know that it’s a shithole—”

“You know why I was in prison?”

“No.”

“For killing a Siete Dos. They arrested me and another guy. The arrest was illegal. Not constitutional. You know what happened to me in there?”

Noe starts to take off his shirt. There are scars all over his chest.

“The guy we killed—his people asked the Aztecas to come get us. So, they did. You see all these scars? Those are knife wounds. Over thirty of them. You know who did that to me? Aztecas. You know what that tattoo is that Manny has on his shoulder? That’s an Azteca tattoo. You know what that means?”

I shake my head.

“It means that I should kill Manny.”

Noe stands up and flexes. “Yo soy Mejicle. I’m a fucking captain!” He’s raising his voice. “You know what that means? It means I shouldn’t be living in a fucking shithole behind my mother’s fucking house. But I am. I am because when I got out, my people said, ‘What do you want to do, what do you want to be?’ I could have been anything. But I told them, ‘I just want to go home. I just want to be a normal person.’ A captain doesn’t do that. A captain has soldiers. A captain makes fucking money. A captain gets all the pussy and coke that there is. But I just wanted to go home. So, they let me. And here I am living in this piece of shit place. I could be rich, but I’m poor. And Manny? I should kill him. You understand? I should kill him but I don’t.”

That night, Manny Carrizales Rios is executed. He and two friends are sitting on the floor of his living room drinking beers when they hear a knock at the door. Someone outside says that their car has overheated and that they need water. Manny gets up and unlocks the door. Three masked gunmen barge in and order Manny and his friends to the ground. The gunmen go around the room, pulling up the shirtsleeves of each hostage. When one finds Manny’s Aztec tattoos, he says, “Here it is.”

The sound of a pistol isn’t nearly as loud as people expect. In Manny’s case, the first bullet enters through his temple and ricochets around his skull. Manny lets out a groan. His eyes roll back in his head. The gunman fires a second time at his heart. Then, the three men leave. Manny’s two friends lie face down. They don’t move even after they hear the gunmen speed away.

The next morning the road leading into Anapra is empty. I have the visor down, the tinted windows up, and a hat pulled low across my brow as I turn off the paved street and onto a dirt road. As I crest the hill that leads to Manny’s house, I see Manny’s brother, El Chato. Chato’s eyes bore into me.

There’s a crowd at the family’s front door. Neighbors, family, friends. Abuelita is sitting on the patio, and as I step out of the car, she rises then collapses back into her chair, breaking into tears. I walk over and wrap my arms around the old woman. She is shaking.

The authorities took Manny’s body last night. Manny’s eldest brother, an evangelical preacher, is trying to retrieve it from the city morgue.

Everyone is convinced that Noe killed Manny. What the hell was Manny doing with a rival gang leader? I hold my tongue, unsure what to think. And then my phone begins to buzz. I ignore it at first. But it continues. Over and over. I pull the phone out. A restricted number.

“Hello.”

“Get out of there right now.”

It’s Papí.

“Drop everything. Run to your car and get the fuck out.”

I look to my left and to my right and swallow hard.

“Now man,” Papí says. “Right now.”

Abuelita is sitting next to me. I tell her I have to leave. There are tears still running down her face.

“Dios te bendiga y Dios te protege entonces.” God bless you and protect you always.

I nod and try to smile, then walk quickly to the car and speed off.

Three days later, an agent from the FBI’s intelligence division calls. The Bureau has received information indicating that my life has been in danger.

“We’re being told that two cars full of state cops were on their way to kill you three days ago,” he says.

I listen in silence.

The Bureau’s sources say that it was off-duty cops who did the hit on Manny the night before. It was a decision from higher up. Powerful people.

“There were actually supposed to be two hits. You were the second,” he tells me. “We know you went back the next morning. Word went out pretty quickly when you showed up again over there.”

The agent tells me that the Judiciales set out that morning to finish the job.

“I imagine you probably passed them on your way out.”

Juárez is full of information. Some of it real. Some of it lies. I don’t know what to make of this call. It’s not what people are saying on the street, but who knows where the truth lies? The agent cautions me against ever returning to Juárez. I ask him if there is reason to worry that trouble could follow me back to the United States.

“No,” he says. “I don’t think so. These guys are already on to the next thing.”

Papí and I still talk on occasion. We trade stories and ask after each other’s families. He always asks about Manny’s family. Papí knows that I send a monthly wire to Manny’s mother, that I call them. He worries about the old woman. He worries about the whole family. But there’s nothing he can do. He’s moved on too.