The soldiers at the gate are not pleased that I have invited a Taliban commander for tea.

“What the fuck?” they say, laughing but sort of not laughing. “You mean we gotta search that motherfucker? Man, shit. I mean, if he’s, like, wearing a belt.”

By belt they mean bomb. Suicide vest. Like the one a Jordanian double agent detonated a few days ago on Forward Operating Base Chapman in the province next door, killing several employees of the CIA. It is on the soldiers’ minds while they stand cold and bored beside the only road through this winter valley, searching each local laborer who enters their base to lay stones in the mud or slather cement onto the rocket-resistant buildings. They know that by the time they would notice a bomb, ruffling their hands through folds of Afghan clothing, the future would already be decided.

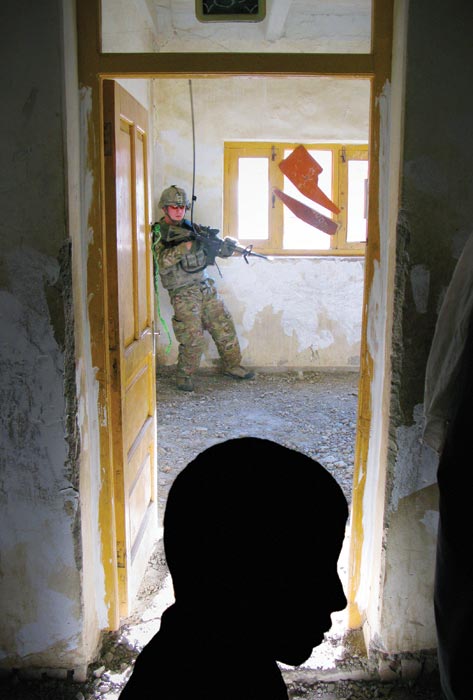

I bet he won’t be wearing a vest. This commander has sworn off war. He doesn’t want to blow things up, at least for now. The soldiers are not convinced. Dude, they say, lifting their eyebrows and shifting the weight of their rifles. In the distance, the high mountains are white with snow. When he finally arrives, small, alone, a scarecrow of a man, the soldiers’ worry fades.

“This guy? A Tally-ban? Really?”

With an armed escort we walk into the base, past the barracks of the Afghan National Army, the scent of pot drifting out. It is surprisingly thick, but not so thick as in the summertime, when the fighting was at its worst, when you could stand there at night in the dark and the humidity, under the heaviness of that smell, and you could imagine sitting inside one of those plywood fishbowls and smiling as the joint traveled to you. My guest doesn’t seem to notice. Maybe the fighters under him were high a lot of the time, too.

We enter a special room furnished with cushions and carpets; the smell now of cardamom and unwashed feet. The commander chooses a cushion against the rear wall and not below a large poster of Afghan President Hamid Karzai. His beard is thick and dark. A round cap of beige wool, a beige blanket over his shoulders. His traditional shirt and pants are pale green and so large he disappears in them. On his wrist a loose silver watch.

His name is Noor Muhammad, and he sits calmly, expressionless and heavy-lidded. A stillness settles through the warm room. In a corner, the soldier who has accompanied us begins nodding off, rifle in his lap. Muhammad exudes no menace; on the street he would be invisible. Soldiers working in intelligence later tell me that Taliban fighters rarely look imposing or dangerous, the way villains should.

Muhammad speaks slowly and deliberately, signs of a life spent among mountains. He possesses the sort of patience or resignation that often stems from faith in the omnipotence of God. He tells me what pushed him to fight the Americans, how he trained in Pakistan, and why he ultimately chose to stop his war. The story is complicated and long. Implied within it is a belief that few decisions are final, that such things as victory and peace are not decided by men. And this is interesting, because he is one of the few to have come down out of the mountains, to have defected from the Taliban. It is to men like Noor Muhammad that the US and its allies will pin their hopes for the future.

Winter changes war in Afghanistan. Violence slows, coagulates. Like sap it waits for a warmer time, for more plentiful food and easier travel, when it can explode again through the valleys and the mountain passes. Spring and summer are usually more violent, and together they’ve been named the fighting season. But like seasons this war has no hard calendar edges. In some places—southern Afghanistan, for example—fighting continues despite winter’s arrival; there the violence seems a measure of the war’s peculiar intensity and perhaps the desperation of all sides. Over large portions of the east, however, the winter calm has returned, and in it appears the other side of combat, all the chaotic work, the competitions for loyalty and good PR, the push to better civilians’ lives. Everything that is done without guns but that is equally important in the struggle for Afghanistan. Winter is sometimes given a name, too: the talking season.

In December and January, I traveled through three eastern provinces to see what this winter meant to the war. All the details of that noncombat work were intense and vibrating in the afterglow of the early-December speech President Obama had made on grand strategy. Withdrawal will begin in 2011, he said. Nothing is open-ended. Although its shape and timing remains unclear, an end is near. Afghans must assume responsibility for their present and their future. I began to see an understanding, or at least a common confusion, unfold between Afghans and Americans. It was linked to Obama’s plan and appeared in many conversations, in official or informal meetings, in cushion-lined rooms or the centers of tiny villages. In many voices civilians and soldiers were repeating it to each other: Now it really is just a matter of time.

I arrived at a small US Army base, called Combat Outpost Honaker-Miracle, slightly more than a week before Christmas, around the time news stories at home had begun to seriously cover shopping. Honaker-Miracle is named for two dead soldiers, and it sits roughly a dozen miles from the Pakistani border in Kunar Province. The base is a near clone of the many outposts strung like knots through the region, small encampments of mud and stone, plywood and concrete, encircled by blast barriers and watchtowers. Buildings with walls a foot thick and resident packs of feral dogs lounging beneath the barracks.

In its roughness and severity Honaker-Miracle mirrors the mountains surrounding it and the violence enduring within them. The Pech and its tributary valleys, including the Watapur and the Korengal, have seen some of war’s severest fighting. They are remote and rural, literacy is low, religious conservatism deep; although the distance between valleys and villages isn’t so great on a map, the lone road through the Pech was only recently paved and the hard-rock geology of the place, combined with invisible tribal boundaries, have meant isolation and little development for the valley and the province. The jihad against the Soviets was born in this landscape. Some Kunaris thought, upon seeing the first Americans, that they were simply Russians who had never left. The old ghosts lingering.

Since the days of the Russian war, Afghan fighters have in winter retreated over Kunar’s mountains to Pakistan to regroup, resupply, rest. Through the same passes the Taliban now travel, along with smuggled guns, drugs, and ideologies. American commanders told me that this year some fighters had indeed headed to Pakistan. But they believed there was more to the quiet: in the late fall special-operations attacks had killed several high-level commanders and fighters. Surviving fighters appeared to be disorganized and poorly trained. Frequently they fired mortars and grenades at the American bases, but they rarely seemed to do much damage. Soldiers often said they had killed the Taliban’s A-team; those remaining were the B-team, or even the D-team. In other words, a sergeant said, “They’re retards who can’t shoot very well.”

Attributing the pause in fighting entirely to “retards” or the cold or any single factor was nearly impossible, and everyone seemed to have a different theory. Lieutenant Colonel Brian Pearl, commander of 2nd Battalion, 12th Infantry Regiment, which “owned” the Pech, told me he thought the drop in violence had to do with American successes that had crippled the Taliban. He said several of the area’s Taliban shadow governors had not made the usual trek into Pakistan. They hung on, like fugitives, still attempting to influence and intimidate, still working to create a parallel government that could command obedience.

“You know what that tells me?” Pearl said one evening. “They’re working to recapture momentum. They know they’re on the ropes.”

We sat in his plywood office on a blacked-out base in the central Pech. He had just spilled coffee across his desk and then mopped it up with calm speed. His office was spotless.

“This year,” he said, “they can’t take a vacation to Pakistan.”

There was the sense everywhere of a tipping point, doubt as to which way it would go. Pearl believed the lull could outlast winter because his soldiers had made the Pech more secure. As long as they kept it so the Taliban would run out of steam. He would not let the shadows regain power. None of the Afghans I spoke with agreed. They thought fighting would return with spring; it always had. Pearl knew this, and it concerned him. Part of his job was to battle the very perception that fighting would resume. It was part of a wartime PR campaign, emblematic of the greater struggle here for loyalty, faith, and, as Pearl noted, momentum. To admit the lull was ephemeral would be to admit progress on the eastern front was limited, or worse.

Whatever the reasons, Pearl’s soldiers were occupying the calm, doing what they couldn’t do during the fighting season. They were sowing a winter crop of ideas and development projects, hoping they would take. Fighters still roamed the mountains and sheltered in the villages. Each time I traveled with soldiers while they patrolled the Pech on talking missions, Taliban fighters watched from hidden positions. We intercepted their radio calls, heard them discussing us, armed voyeurs debating when to stop watching and start firing.

Lieutenant Tom Goodman was annoyed. He had come expecting a shoot-out, but first he must sit through this. The hike up to the village of Qatar Kala had been hot; sweat glistened on his forehead. It was late December, a few days before Christmas. Snow lay on the peaks in the distance like a promise, bright and clean. But where Goodman sat, all was dust-covered and filthy, everything fading into the desiccated beigeness of winter in eastern Afghanistan.

The village elders sitting in an arc around him weren’t saying anything new. Conversations with civilians had reached a kind of theatrical state, like a play past the middle of its run—the actors familiar with each other’s lines, their cues embedded somewhere beyond memory. Goodman asked how things were going and the elders answered they were fine. He asked if Taliban fighters had passed through recently and they said no, not here. Goodman was fairly sure this was a lie. He was sure men like Noor Muhammad visited the village often. His men had been patrolling and fighting in the Watapur Valley for six months, and Qatar Kala lay just below the “red line.” Above this line was a zone the Americans rarely entered without heavy support because there, in the higher elevations, the Taliban remained in control.

Goodman could not read the Afghans’ faces, didn’t try too hard. One man’s mouth hung open, as though in idiot wonder, his teeth mostly missing. Another’s eyes were hidden behind John Lennon sunglasses. A third old man squinted, his face lost in his beard, his hands hidden in enormous black gloves fit for ski slopes. Goodman, twenty-three years old and leader of Third Platoon, Chosen Company, was not there to read body language. He had come to deliver American foreign policy.

“We really want these fighters to reconcile with us,” he told the elders. He sat on a large stone worn smooth with use in the village center. “Please spread the word, get these guys to come down out of the mountains.”

It was both charge and appeal—I know you know the bad guys. Tell them we want to talk. Far above Goodman, allied commanders and politicians had already decided it was impossible to kill or capture all the bad guys. There were simply too many militants, fighting for a scatter of reasons (many of them not ideology but merely money), across brutal terrain that not even the American military could control. Reconciling—attempting to convince these fighters to lay down arms and join the new Afghan society—would be crucial to pruning the violence. It was perhaps the only hope of creating something like lasting peace. A while after Goodman’s visit to Qatar Kala, in late January, many of those higher-ups would gather at a conference in London to discuss the future of Afghanistan, and they would announce their intent to reconcile with as many anti-government fighters as would accept. President Hamid Karzai would name it a centerpiece of his strategy. But that was still weeks away. For the moment reconciliation was just another talking point.

Third platoon had walked out of Honaker-Miracle at noon, sunlight glazing the mountains. They had passed through a small town where Afghan men and boys and unveiled girls stood staring. The soldiers turned up a narrow road and into the Watapur, through an ancient geometry of fields, terraced and irrigated with slender channels running like veins under the soldiers’ feet. In the low branches of the trees golden cornhusks had been stacked to dry. Aside from the burbling of water and the distant laughter of children, the valley was silent. But the Taliban would soon begin speaking. Whenever a patrol left the base, enemy spotters marked it. An interpreter who worked for the Americans said he was worried. His real name was Mohamed, but everyone called him Steve.

“This village,” Steve said. “Always trouble these fucking guys.”

And so it had been: through the spring and the miserable summer heat of the fighting season, Goodman’s men were always under fire from somewhere, often from an enemy they could not see who hid on slopes studded with boulders. Some of them might have been Noor Muhammad’s former fighters. Goodman returned from summer patrols so dehydrated that he and his men could do nothing more than sit and surrender as medics jabbed them with needles and started IV drips. Even pointing a finger to show where they had walked brought cramps.

The platoon was like most I traveled with in eastern Afghanistan. They were rolling out parts of the counterinsurgency strategy that now dominates military thought, where soldiers focus on protecting civilians and, when possible, knitting in strands of development, governance, and other ingredients of nationhood. Every conversation with Afghans also echoed themes from Obama’s speech: Take responsibility. Stand up. The language of leaving.

Delivering the messages and concepts was complicated. Soldiers and Afghan civilians did not share a common cultural vocabulary. They didn’t even share an understanding of the American mission. Worse, the interpreters upon whom the soldiers relied often had a questionable grasp of English, and many soldiers told me they believed at least half of what they said was lost in translation. Frequently they bogged down explaining to Afghans the very idea of nation, what one is, what it does, the role of citizens. Drive-by civics lessons.

Tangling matters further was a recent, major shift in the American approach, also stemming from Obama’s plan. In previous years Afghans had gone to the Americans with their needs and desires. They did not trust their government, and it had rarely touched their lives in positive ways. They were comfortable turning to the Americans for help. But the system had suddenly changed. Just before my arrival the Americans began telling Afghans to bring their concerns, problems, and requests to their own leaders. Goodman’s commanders and officials from the Department of State and other US agencies explained this transfer of responsibility as “connecting Afghans to their government.” The Americans were sidelining themselves. It was a strange calisthenic, especially in the Pech, where the Afghan government often seemed weak and distant.

Living conditions in the valley had slowly improved—schools and clinics had been built in recent years, and Lieutenant Colonel Pearl had lately directed his men to coordinate small projects, such as digging wells and building retaining walls. Things that could be funded by a Tom Goodman carrying a pocketful of green-blue Afghan bills and that would make quick, direct improvements in individuals’ lives. It was a move toward tighter accounting and away from the practices of the past, Pearl said, when streams of cash had been poured into sprawling projects that easily fell victim to corruption. Also it was a retreat from large, long-term commitments.

Soldiers joked that in winter they became building inspectors, killer contractors carrying rifles and to-do lists, checking to see that flushers had been installed in the toilets at the school, that bags of cement were distributed equally. Pearl once said that “you could conquer Kunar Province with see-ment,” his Midwestern accent showing. The effort appeared to be catching on. Some of his soldiers had even noticed that attacks against them seemed to drop off when shipments of cement were expected.

But no Afghan I met attributed these improvements to their own government’s largesse or competence. They knew the money and the stuff wasn’t coming from Kabul. They loved cement, new roads, bridges; but they weren’t about to bestow loyalty on donated infrastructure. It seemed a point the Americans routinely missed. Often they defaulted toward construction, as though alone it could stop the shooting. “The insurgency begins where the road ends,” Pearl told me. Where the road ends, the Americans longed to build more road. An American trait, engineering easier than philosophy.

For their part, soldiers welcomed the responsibility hand-off. They had grown tired of the constant requests and demands. Soldiers said the Afghans mostly thought of them as ATMs or Walmarts, and they considered many Afghans rude, greedy, corrupt, and possessing a tendency to try to collect on promises of money or materials that had never been made. Some Afghans became so notorious among the soldiers that they earned nicknames.

Once, on a patrol in the Watapur Valley, a soldier pointed to a heavy man in the center of a flapping crowd. He was yelling about cement; he wanted more.

“That,” the soldier said, “is the Douchebag of the Watapur.” As though it were a royal title.

Afghans had their own complaints. They said Americans were biased as to whom they gave supplies or in which contractors they hired. The Americans could not see who was corrupt, who was stealing, who had a powerful cousin in the government. Despite these sores, the recent shift confused and dismayed a lot of Afghans, many of whom told me they’d rather deal with the soldiers than their own government. Americans were infidels, sure, but at least they got things done. Weaning will be painful.

Qatar Kala wasn’t getting any more development aid for now. The Americans had already installed several solar-powered lamps, like streetlights, around the village center, but that had not stopped fighters from shooting at Lieutenant Goodman’s men. It enraged soldiers that villagers seemed to have no problem requesting American help and then, later, providing shelter to the Taliban. Qatar Kala’s residents were incapable of living in the black-and-white world that Americans, especially young soldiers, yearn for. So Goodman said his piece, professionally but without emotion: Get those guys to come down and reconcile. He did not remove his black Terminator sunglasses.

The elders listened silently to the translation. No American had come to this village and said these words before. It was a fresh addition to the weary dialogue. They absorbed it, their faces unmoving. Between the red line above them in the mountains and the Americans below in the valley, they lived tentatively, removed from whichever side they might choose. Certainly some of their relatives fought with the Taliban. Later in the evening, the Taliban might even visit with their own pitch. Possibly it would include violence. Already they were near; the soldiers were picking up their radio traffic. The elders told Goodman to leave.

“We will consider your message,” an old man said, his long beard the color of pewter. “Now, it is better if you go. For your safety.”

Goodman looked around. His men stood guard against mud walls where discs of cow dung had been flattened to dry, still marked with the handprints of those who had scooped and shaped them. Streams of stinking water ran through the dirt alleys. Goats wandered in and out of buildings, freer than the women hidden within. And all around him young men and boys stared because it was not their place to speak. Medieval. Little but the chop of attack helicopters above, the implied threat of machines, suggested the year 2010.

Goodman waited but the elders said nothing more. Okay, then. Fuck it, he thought, and stood.

Later, as we hiked down, Goodman said, “It’s what they always say: ‘leave now for your safety.’” He laughed. “They should be the ones worrying.” But he also remembered the many ambushes he had walked into in the Watapur. One of the battles lasted ten hours. The elder’s words may simply have conveyed distaste for soldiers, a desire to be left alone. Or they may have contained something more. Goodman looked out over the valley, over the sleeping fields.

“This is when we usually get hit. As we’re leaving.”

He had been thinking lately of home. In a few days he would go on leave, back to Maryland with its grass and trees. He would probably stop and buy jeans on the drive from the airport; then he hoped to catch friends on the upside of a night out—his first in months. If he was lucky in the timing, it would be New Year’s Eve. But first there was this.

The platoon weaved down the valley. Children with fierce, beautiful faces appeared along the trails, the girls braver than the boys, green eyes lined in black, freckles showing through the soot. Like Irish orphans. In a few years these faces would disappear forever behind shawls blue as the sky, but that day they were curious and full of defiance. The children said nothing; the soldiers said nothing. Many of the soldiers no longer liked the children, the way they swarmed, constantly asking for biscuits, candy, watches, knives, everything. They called them “seagulls” for their tendency to flock and scavenge, to tear into each other over tossed bits of candy. What had been novel was now repulsive. The story of war.

The soldiers walked on, counting the days, on the outside edge of a turn toward something like conclusion. In the mountains above us the Taliban watched and called each other on the radio, but they did not shoot. Perhaps they were only the B-team, not quite ready to bet their lives on the game.

Sitting at a wicker table in his private courtyard in the city of Asadabad, Fazlullah Wahidi, governor of Kunar Province, watched a peacock step slowly through thick afternoon light. It was brilliant, a gem in the muted wrap of winter, the eyes in the tail feathers laid up in close bundles. There were other birds in a large cage nearby, big doves with tumbling calls, ornate chickens. But the peacock. I would see them elsewhere in the east, kept by minor officials in shabby government buildings, the cock usually given a room of its own, shitting all over the place. Sometimes Wahidi’s bird fanned its tail and it seemed we were being rewarded.

Wahidi is one of the more highly regarded governors, at least from an American point of view. He does not come from warlord stock. He was educated at Kabul University and worked for years with NGOs in Pakistan and Afghanistan. When State Department officials and military officers spoke of him, they often used a popular catchphrase: acceptable levels of corruption.

“He probably takes his little kickbacks,” a woman from the State Department told me one morning. “But it’s nothing like some of the other governors.”

Then she added, almost dreamily, “You know what they say in Afghanistan. The hardest thing to find is the truth.”

If corrupt, Wahidi was considered benignly so. It was a measure of reality that Americans in the war zone had absorbed, despite all the public worrying over corruption back in Washington. Wahidi was realistic, too. There was much to be hopeful about, he said, but the war was not going well. He believed reconciliation could help turn the tide.

“Reconciliation is very important,” he said. “We have many Afghans who are unhappy and who fight. But they are not all necessarily enemies. We must work to bring them in.”

He brought his hands together and knit his fingers, a gesture of mending.

“And, if we also bring people out from the hands of the Taliban, then we make al Qaeda weak, too. This is in our interest and yours. Our main problem is al Qaeda.”

For too long NATO allies had pursued strategies that left little room for talk. That black-and-white perspective. You’re with us or you’re against us. The Afghan government had tried a reconciliation program in the past, Wahidi said, but it failed because the government tried to lure Taliban fighters out with cash, jobs, and offers of protection. Then it didn’t, or couldn’t, deliver. Some fighters simply rejoined the Taliban. The new program would require American support and more: it would have to accommodate gray zones of Afghan culture—the notion that an enemy might on Monday be swiping for your throat and Thursday be sitting in your living room.

Later in my trip I spoke with a black-turbaned elder from a remote village that was generally considered allied with the Taliban—if not one of their strongholds. The elder met regularly with the Americans, but he always came alone and pleaded for more help. Approaching the Taliban was crucial, he said, and then he put it like this: “Your president, Obama, he talks to the North Koreans. He talks to the Iranians. Why would he not talk to the Taliban?”

Most Afghans I met agreed. It is not uncommon to hear them call the Taliban “brothers,” as though they were merely lost or misguided and might one day return to the fold. Seen that way, reconciliation is a path home. Wahidi thought so, too.

Our conversation skittered along the surface of the idea; there was not much depth to it yet. Goodman and other soldiers had recently begun hiking the message into far-flung villages, but, as with everything else, the ultimate responsibility was being shoved onto Afghans. Wahidi, at the official center of local responsibility, knew this, and he knew his government’s shortcomings.

“The previous system was only talking,” he said. “It wasn’t good. There must be transparency, so the people can see what we are doing. Then we must give these fighters jobs and protect them. It is giving them the possibility to live normally in their own area. They should think they are safe, like other people.”

The reconciliation program was so new that no one in Kunar knew its official name, if one existed. No one knew how it worked. Everyone hoped it would carve so-called “fence-sitters” and low-level fighters away from militant groups—though who would be allowed to reconcile and what they’d receive if they did was unclear. The idea was being cast across the rugged landscape as a farmer might cast seed, with a prayer for rain and sun, a plea to unseen forces to do the hard work. Later there might come fertilizer. Wahidi was encouraged by a recently convened jirga—or council—called by regional elders on the subject of reconciliation. Leaders from some of the most violent areas had attended. There was interest.

“It’s not difficult,” Wahidi said. Through his fingers he worked a string of prayer beads the color of sunrise. Doves purred beside us. “We need some time for the people to believe us. To believe we do more than talk. There are many groups of fighters waiting to see what we will do.”

We rose from our seats, Wahidi late for afternoon prayers. I liked him. I did not believe it when he said it wouldn’t be difficult. Reconciliation had already failed once, and in many ways the Afghan government had not grown stronger or more capable; there was so far little to suggest this time would be different. That Afghans and their allies were trying reconciliation again at this point in the war made it seem momentous. But also there was a sense of urgency, of a last-ditch run.

Lieutenant Colonel Pearl told me three fighters had recently come down from the mountains to reconcile. Two of them were murdered by their former comrades. The third must have been wondering about the wisdom of his choice.

“The Afghan government can’t protect them yet,” he said. “It has to be able to do that for this to stick.”

When US troops rolled into Kunar Province at the start of the war, they quickly chased the Taliban out. Noor Muhammad decided the Americans were invaders and he decided to fight them. It was what Afghans like Muhammad had always done, since the time before the Prophet. Since the time of Alexander. Muhammad also believed the Americans had come to destroy Islam, and defense of his religion became holy motivation. He explained this while sipping apple juice from a box inside the headquarters building at Combat Outpost Honaker-Miracle. A place he once would have targeted with rockets.

Muhammad joined the Taliban sometime around the end of 2001. He soon traveled to Pakistan, where, he said, he was trained by “the Pakistani CIA,” by which he meant Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), the spy agency that in the 1980s had partnered with the American CIA to fight a proxy war against the Soviets using men like Muhammad. He did not know at the time, as he crossed the mountains, that the Pakistani government had also pledged its support to the US in its new war on terror.

Muhammad learned to shoot and fight, attack and move. He learned something of explosives. “But mostly,” he told me, “they trained our minds. They said the Afghan government was un-Islamic because it was working with the Americans, so it was okay to kill them.”

For Muhammad and many others, Pakistan provided an escape clause to the Islamic commandment that forbids Muslims from killing other Muslims. When he returned to eastern Afghanistan, his spiritual framework was firm, his ideology twinned with action. He began as a foot soldier, using rocks and landscape against armor and technology, David-and-Goliath tactics proven long before they drove Lieutenant Tom Goodman and his men to frustration.

Within a few years, Muhammad was promoted—to commander of some sixty fighters. He does not say much about the details of battles or specific attacks, but US soldiers confirmed that Muhammad once controlled Taliban operations in the Watapur Valley. In the regional scheme, he was not a small man at all. Not the passive man who appeared before me.

For a while, Muhammad’s war ran smoothly. He said that during this time he often took instruction from Pakistani agents, merging his missions with their desires. During the Russian war, Pakistan routinely sent agents into Afghanistan to coordinate attacks. That they were doing it again was perhaps not surprising, until you recall that Pakistan was a US ally.

Over time Muhammad began to see his mentors and their orders differently. His faith in them eroded.

“They started telling me to blow up schools and bridges,” he said. “I know what Islam says. At first I had thought, the Americans are destroying my country. But then I thought, Pakistan is destroying it. I started to see them as un-Islamic. So I started to change my mind.”

This was around 2006. The Taliban had been regrouping, rebuilding, mainly in Pakistan. It was the time of their revival, and they streamed back into the cities and mountains. The Americans had turned their attention to Iraq, neglecting Afghanistan, and the resurgence threw them off balance. At home, ordinary people began talking of losing the war. After a while, even generals talked that way.

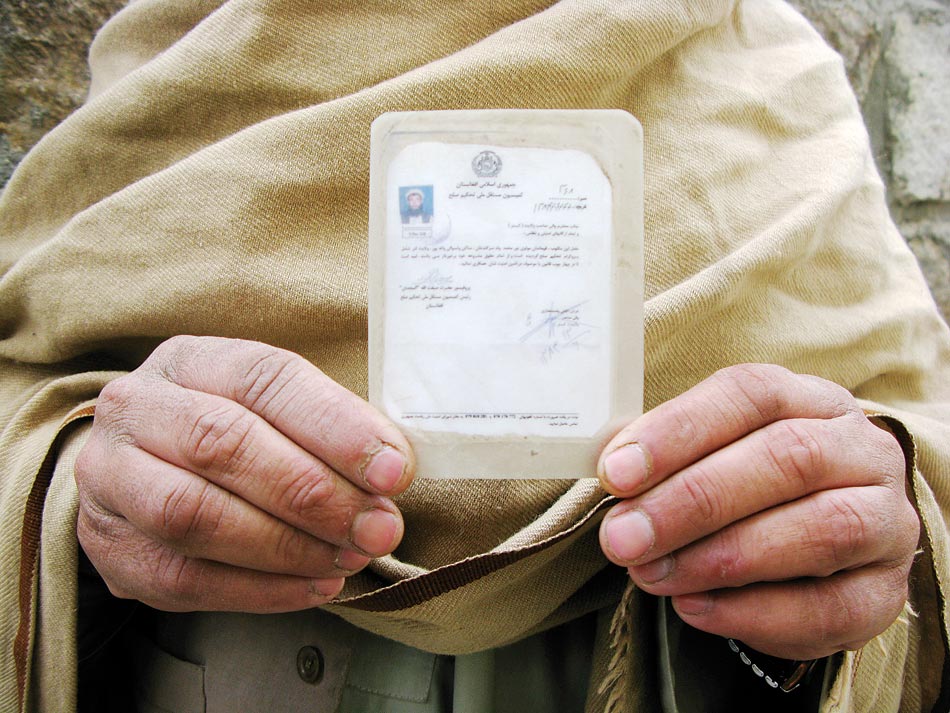

For Noor Muhammad, the war was already over. He had come to hate the Pakistanis, and possibly—though he didn’t admit this to me—he was tired of fighting. He had been surrounded by violence all his life. Elders from his region had asked him to stop, and the provincial governor at the time (not Fazllulah Wahidi) appealed to him as well. So Muhammad decided to reconcile and swear allegiance to the new government. He surrendered a cache of automatic rifles, rocket-propelled grenades, boxes of bullets; and he brought five of his fighters down with him. In return, the government promised safety and compensation. He began considering a new life. He could never return to the mountains, at least not while his former Taliban comrades controlled them.

Muhammad said the government paid him $400 to travel to Kabul. There he was given a plastic ID card and a single sheet of paper detailing what he had done—announcing to all who could read that he was no longer an enemy. He was given nothing more for his defection. Soon he found the government didn’t back its promises. Soon the Taliban began killing his relatives in revenge. Violence follows him still: a few days before we met, the Taliban beheaded one of his nephews, a fact verified by US soldiers. The paper and the ID card he was given are virtually worthless in the Pech Valley, where few can read them. But they look official. Muhammad had carried them to our interview and he repeatedly offered them to me. But I couldn’t read Pashto, either.

Today Muhammad lives in a rented house beside the grey Pech River, not far from Honaker-Miracle. He is a father of five. His hands are rough, his fingers thick; a laborer’s hands. This is his work now, when he can find it. He told me life had gotten worse for him.

“Yes, I regret it,” he said flatly. “Up there, I was a commander.” He waved at the mountains. “Now I’m a laborer. I thought I would be able to convince others to stop fighting, but now they say, ‘Why should we? Look what happened to you.’”

Muhammad has become an example of what not to do. I asked if he would fight again, as some had done upon discovering the emptiness of the deal.

“No,” he said. “My heart won’t let me do it. I hate them both—the Taliban because they killed my relatives and the government because they broke their promises. What I need is work. My men need work, too. If the government kept its promises, more fighters would come down.”

There is talk of employing reconciled fighters in the army or police forces, as had been done with militiamen in Iraq. Muhammad suggested he would accept such a job, but so far there hasn’t been an offer. For now Muhammad seems to inhabit a no-man’s-land—or at least the territory where many other Afghans live, between the crush of armies and ideas, fearing or hating both sides, the horizon a border at which new enemies may tomorrow appear. Still, it has been four years since he left the Taliban and he has not returned to them. A good sign. Perhaps he truly doesn’t want to; perhaps he hasn’t hit bottom yet.

Muhammad’s tale is cautionary, a lens on all the opportunities lost in this wasted and beautiful landscape. But there is still promise. During my travels in the east, US officers spoke of a recent special-operations report that found more chances might exist to peel fighters away from militant groups than previously thought. They said that, during questioning, some prisoners had revealed that they fought because they were told Americans had blasted into Afghanistan to destroy Islam—much like Muhammad had believed.

Also like Muhammad, these fighters eventually reached their own conclusions about what the Americans were up to. Seeing that Islam was not necessarily under threat, or that Afghanistan was being hurt by other forces (Pakistan, or foreign al Qaeda fighters, for example), they began doubting their superiors. When they were not mistreated by the Americans—they’d been warned to expect torture—the fighters realized even more. The report may have been a kind of inter-office PR push, the US military producing its own rosy memo. But Muhammad’s story lent it weight—a possible crack in the armor of enemy ideology.

My interview with Muhammad ended. We walked to the gate, past smoldering piles of trash, past the stoned Afghan soldiers in their shacks. Mountains rising in gray-green chevrons before us, fields of boulders numerous as the stars and Muhammad’s old home somewhere among them. I remembered the guards at the gate and how they worried before Muhammad’s arrival then mocked him when he appeared less than monstrous. It was tempting to feel sorry for him; he portrayed himself as a kind of victim. Soldiers later confirmed much of his story, but there were parts they could not confirm, parts they doubted. In Afghanistan, the hardest thing to find is the truth.

All through the interview, I had been watching for signs of the war commander, the man the Americans feared and the fighters respected. The man who had crossed mountains to kill for God. There was only a hint, in the flatness of his eyes, a certain look that did not lift. He did not appear troubled when considering his future. He seemed mostly to live in the moment. Perhaps this is the most dangerous kind of man.

A few days before Lieutenant Goodman was to go on leave I joined his platoon for a patrol into the mountains. His men would provide support for another platoon as they visited a small village for the first time. We left Honaker-Miracle in trucks and drove a kilometer or so up the Pech Valley to another, even smaller, outpost called Able Main. We spent the night in a plywood rec room littered with paperbacks and cardboard boxes stuffed with toothpaste, deodorant, leaking shampoo bottles, junk food—all of it donated by the American public.

Some of the men slept on cots, some on the wood floor, curled in sleeping bags or sacked out in their clothes; small, boyish forms in nests of guns and gear. All night a large-screen TV blared football games and recaps of games over and over. No one could figure out how to shut it off. We woke up feeling hungover, but without memories of any party, any fun.

With the first light we began hiking up into the rocks. The plan was to arrive early, before the Taliban would realize what was happening. Goodman’s platoon went ahead to ascend a ridgeline, where they would set up defensive positions and provide cover as the other platoon headed for the village. I decided to join this platoon, led by another young lieutenant named Mark Harris. We hiked for an hour, through scrub and scree, through an Afghan National Army outpost crowded with sluggish soldiers and scented, again, with dope. Finally we saw the village, a place called Khaki Banday. From a distance, it looked like a resort, or perhaps a vineyard. Green, terraced fields stepping up to stone buildings with porches and large, timber-framed windows. Soft light warming the stones. A suggestion of arbors and ivy. Up close the rooms were filled with goat shit and the walls were crumbling.

It’s a dangerous area. Khaki Banday is the last stop on the Americans’ patrol circuit; above it is another red zone. The alpine hold of the enemy. The goal, the lieutenant told me, was to make contact with local elders, feel them out, begin winning them over. (Begin? I couldn’t help thinking. Now? After nine years?) They might also discuss reconciliation, or battle the Taliban, whichever particular challenge presented itself. “These guys are always begging for development projects,” Harris said. “But we never give them any.”

“Why not?”

“Because we always take contact up there. Soon as security improves, we’ll do something.”

When we reached the village it seemed deserted. But eventually an old man appeared, and the lieutenant spoke with him through an interpreter. The man’s name was Mohammed. He was not sure how old he was. “Sixty?” he offered. Harris asked if any Taliban had visited there, and the familiar conversation began.

“None!” Mohammed said.

“How can it be none?” Harris said. “We get shot at from here.”

“Not from here,” Mohammed insisted. He pointed to the sharp ridges above Khaki Banday, treeless bands of earth, rock like exposed bones. “If they shoot at you from up there, you say it is us. If they shoot at you from over there, you say it is us. Always you say it is us.”

“So they never come to your village?”

“Never.”

Harris sighed. There was still the return hike to consider, when our backs would be turned. Somewhere just beyond us in the mountains the Taliban were stirring. They had seen us.

“We need the shooting to stop,” Harris told Mohammed. “You have to take an active stance. These are your people, your villages. You have to push the bad guys away.”

“What can we do?” Mohammed said. He swung his white beard to the north, to the area the soldiers would not go. “I am not responsible for those villages up there. I am responsible for this area only.”

He repeated it several times—this area only. Maddening to the soldiers within earshot.

“You are a citizen of Afghanistan,” Harris said finally. “This nation is your responsibility.”

It was the new message again, delivered in a language of exasperation and warning. Harris spoke slowly and it was better that the irritation in his voice disappeared as his words filtered through the interpreter. But behind him, so large as to be unseen, an entire army, an entire country, seemed to shout: Stand up for yourselves, goddamn it, because soon you will be on your own. As Harris finished I asked the interpreter, an Afghan, if he knew what the word nation meant. It became clear that he did not. No one mentioned reconciliation.

Later I asked Lieutenant Colonel Pearl how he expected these ideas actually to take root.

“I think it’s just about repetition, repetition, repetition,” he said. “Getting out there and telling them over and over.”

Then he paused. Weariness seemed to invade him.

“I think these two cultures, ours and theirs, will run parallel to each other, never really coming together, sometimes running at similar speeds, until we’re gone and it’s just them.”

Layers of air, atmospheres of water. The weight and the boundaries felt but not seen. Pearl understood that truly changing Afghanistan requires a timeline and a commitment the US will not accept.

We had left the village and were hiking down when a soldier with binoculars noticed the residents of Khaki Banday retreating into their houses and shutting the heavy doors. As though before a storm. The Taliban were talking on their radios. They noted our location, passed it along to others. They discussed how they would attack. We were a long, thin line descending awkwardly through the mineral hardness. Their voices seemed to flow among the rocks.

“When we see a chance to shoot them, we will shoot them,” a Taliban voice said.

The hiss of the radios shadowed us down the mountain. Helicopters circled above but saw only stones. The soldiers were tired and tense. They watched their feet, trying not to slip, and they waited for the sound of gunfire. They were sure it would come; the voices told them so. But it never did.

Back at Honaker-Miracle, a sergeant working in intelligence told me that a minor Taliban commander had just reached out to him, grasping at reconciliation.

“I got word the other day,” the sergeant said. “He came to me through a middleman. He wants to see what’s possible.”

The message was essentially this: if the deal is good enough, I will stop fighting. He said he might bring three or four other fighters with him, if he came down. For some reason he had not retreated to Pakistan for the winter. The sergeant didn’t know the commander’s motives, and ultimately the work of turning him would not fall to the sergeant, anyway. The Afghan government would have to do it—and do better this time around. The sergeant didn’t know why this commander was interested in reconciliation.

I imagined the man sitting in a small house of mud and stone in the mountains, weighing his options by candlelight or a fire made with dried dung. His beard was stained red with henna and he was wrapped tightly against the cold in scarves and shawls. On the floor a cup of cooling tea, an AK-47. Thumbing prayer beads. Dirt wedged under his fingernails. His thoughts were guided by pride and religion and perhaps by poverty and need. Helicopters clattered in the distance.

It may have been that the war was not going well and he did not like his diminished hand. Or he was tired and looking for a kind of career move. There was also the cold: not far from where he and his men have been hiding, snow covers the mountains and no trees soften the wind. I wondered if he had fought Lieutenant Goodman, if he had watched us hike into the valleys. No doubt he knew of Noor Muhammad.

Perhaps this commander will be among the first in the rain of defectors Afghan and American officials hope for. If they cannot win him over before winter’s end, the talking season will fade into another fighting season and it will be harder. Possibly he will resume fighting. The hills will be less bleak; supplies will trickle over the border again. Reinforcements will arrive. Spring will nurture morale. Many allied military officers told me they believe the 2010 fighting season will be extremely violent, partly because Obama’s surge troops will begin fanning across Afghanistan. But the surge also presages withdrawal.

The troops I met in the Pech Valley and across the east could do little more than wait to see what arrived with spring—if their talking about nationhood, responsibility, and reconciliation would yield returns. For reconciliation to succeed there must be a nation to support it. For a nation to exist the people must understand and believe in it and, at least to some degree, submit to it. These things were incomplete and fluid during my time along Afghanistan’s border; they were still possibilities rather than realities, unguaranteed.

Just before I left Afghanistan, world leaders met in London to discuss the future of the country. Reconciliation was a major theme, along with plans to attempt negotiations with top Taliban leaders. Donor nations pledged of millions of dollars to create jobs for the Noor Muhammads, to back the words Lieutenant Goodman would carry into the villages. To prove, as Governor Wahidi hoped, that the government is not hollow. If one idea becomes real, another can follow.

Still, the scale of all this—the tasks of seeding nationhood among rural Afghans, and of young soldiers attempting to connect villagers and government while convincing enemies to defect is enormous. And the overtures of exit have now been made. Already, despite the surge, we are ebbing.

Peace and stability in Afghanistan, the apparent goals of the American mission, may never exist the way we think and dream of them. Perhaps it is better to consider peace a season, stability a current within it. Like winter. A temporary condition but one that can linger, even for a long time. It might look as the Pech did many mornings. Snow on the distant peaks, smoke hanging above the bazaar and the medieval villages. From somewhere the whir of minor industry and the laughter of children. Light traffic on the solitary road. And then, later, the B-team rising from their nested blankets, firing wild mortars into the light.