- A swimmer off the Malecón seawall in Havana.

August in Havana is a mounting wave of heat—so consuming, the sun so piercing, it can warp your sense of reason. Tempt you to surrender. Make you flirt with insanity. The pained faces around you are covered in grimy sweat, a haze of resignation in the eyes. Here or there a woman fans herself, perhaps with some ladylike, store-bought thing, but more often with a stray scrap of cardboard. Inside, heat radiates from every surface, the temperature rising as the torridity soaks deeper into the concrete walls. Outside is worse. Few dare venture into the scorching light.

And there is nowhere else to go. Havana, for most inhabitants, is an enclosed island within an island—just as she was when the Spaniards built wall after wall of stone to keep out the English and the pirates and all others drawn by the siren song of that wild tropical mirage of women and rum and gambling. To the north is the water, of course, but it is accessible only by climbing down the Malecón seawall and a ring of perilous cliffs. A trip to the beaches east of the city involves hours of waiting in line, then standing for the long ride on an overstuffed bus with no air-conditioning.

In every other direction is green jungle. Even Havana’s neighborhoods explode with the products of sun, water, and the island’s intense fertility: the delicate orange flowers of the outstretched framboyán shade trees, bougainvillea in twists of magenta and purple, squash blossoms peeking from the weeds encircling decrepit mansions now housing handfuls of families, and the red mar pacíficos, or hibiscus, which curl in their blossoms every afternoon.

On a lucky day, this occurs just as the rains come in. The horizon goes from partly cloudy to gray and foreboding, the sky exuding a brilliant, otherworldly yellow. Lightning jags, in white and orange, hover on the horizon, above the imploding buildings. Threatening. Then the aguacero comes down: angry, gigantic drops beating into the ground in long flashes of light. Few Cubans can afford umbrellas, and they resign themselves to the deluges, like so many daily realities—the uncertainty, the drenching, the clumps of clay dirt caught in the torrents turning everything a washy red.

As August goes on, the rains become scarce, and the temperature rises. Walking down the street, visiting with friends, riding the bus—everywhere people lament the unrelenting heat. Will September bring relief? Or will the hurricanes start? Even when the sun sets, temperatures never fall more than a few degrees. Across the city, habaneros (residents of Havana) pray for nights free of blackouts, so their electric fans will not rattle to a stop, so the suffocating heat will be staved off one more night. Then, in the morning, the cycle begins again.

It is in August’s crescendo of waiting and suffering that Cubans often give up on life. But few people in Cuba talk openly about losing one’s mind, much less about suicide. So when, one viscous August afternoon, a woman named Mirta tells me that her nephew killed himself, she does so without speaking.

Mirta* is nearing her sixtieth birthday and has herself battled depression and anxiety for years. She is small and stout and wears her gray hair short with a shock of white bangs. At home she dresses in a sleeveless yellow housecoat to fend off the dirt and stench of the street. Most of Mirta’s time is spent in her living room, where the fluorescent lamp overhead casts a dull gray tone, making the small room seem smaller. Mirta glides in her wooden rocking chair, the fan whirring nearby achieving little but noise enough to mask her words. As she talks about her nephew, she mimes the facts of his suicide. “He . . .” Mirta begins, her voice dropping off. She stretches her thumb and forefinger across her neck, just below her chin—like a noose. Mirta knows little about what provoked her nephew. He had longed to get off the island for years and was also a heavy drinker, but his parents have told Mirta few other details—only that he suffered from los nervios, the generic Latin American term for mental illness.

Socialismo o Muerte. Socialism or Death. In that slogan splashed across Cuba, there is nothing honorable, or revolutionary, about choosing suicide; the very idea is intensely political and taboo. Sit down with most medical professionals in Cuba, in fact, and they will assure you that suicide is rare, that there is nothing striking about the country’s relation to self-destruction. They may not even know the truth themselves, may never have seen the statistics: according to the World Health Organization, year after year, more Cubans commit suicide than citizens of any other Latin American country. The national suicide rate trails just behind that of the People’s Republic of China, of high-strung developed countries such as Japan and Finland, and of a slew of depressed post-Soviet states.

Since written histories of Cuba have existed, Cubans have killed themselves in record numbers as a form of social protest. At the dawn of the conquest, as many as one-third of the island’s native inhabitants committed suicide to avoid living under Spanish rule. University of North Carolina historian Louis A. Pérez Jr. cites sixteenth-century explorer Girolamo Benzoni: “Many went to the woods and there hung themselves, after having killed their children, saying it was far better to die than to live so miserably, serving such and so many ferocious tyrants and wicked thieves.” Pérez continues, “They chose death by way of hanging. They ingested poison. They ate dirt in order to die.” And in a jungle east of Havana, a band of natives escaping slave-hunters threw themselves over the edge of a valley known as Yumurí—its very name a permutation of the Spanish for “I died.”

This national tendency peaked again during the Cuban wars for independence in the late 1800s, when a rebel landowner wrote the lines of what would become the Cuban national anthem: “Do not fear a glorious death, for to die for the country is to live.” The leaders of the struggle, who later become heroes for Fidel Castro’s revolution, included José Martí, the martyred father of Cuban nationhood who fell on his first day in battle, and General Calixto García, who shot himself in the head to avoid capture—and lived to tell the story. As the independent nation grew, more and more Cubans turned to suicide: peasants in the time of unemployment after the sugar harvest, wives escaping violent husbands, the working class suffering economic crises, young leftists facing jail under dictator Fulgencio Batista, and thousands disillusioned by Castro’s transformation of Cuban society after the 1959 revolution.

Like August temperatures, suicide rates have peaked again and again since the 1970s. After the fall of the Soviet Union, the island fell into its own Great Depression, which Castro euphemistically dubbed “the Special Period in Times of Peace,” and suicides spiked to more than double the already-high rate of 1959, becoming the second-leading cause of death for Cubans ages fifteen to forty-nine. (Defected Ministry of Public Health workers claim that the official tallies heavily underreport suicides, with the government recategorizing many as accidental deaths.) Rare Cuban medical journal papers on the topic mention a reality normally unheard of in government spheres: people killed themselves during the Special Period due to “difficult socioeconomic conditions” or, simply, “despair.”

The impact of the Special Period on the Cuban psyche is difficult to overstate. Once, on a visit to Havana several years ago, I remember asking a friend when the Special Period had ended exactly. He laughed, dryly. “Has it?” While the worst of the 1990s is past, Cubans have become accustomed to levels of uncertainty and scarcity inconceivable to outsiders, and, on the whole, they remain subtly traumatized. Mention the Special Period, and you will hear a flood of stories almost too dreary to be true. Like the acquaintance who told me that instead of gaining weight while pregnant with her daughter, she lost fifteen pounds. Or the friend in medical school who hitchhiked to school every morning on a breakfast of sugar water. Or the friend who went weeks and weeks without soap or toilet paper. “It was as if,” they will tell you, “we were at war.”

Since the handover of power last February from Fidel to his brother Raúl, much has been made in the international press over reforms on the island, but there has been no change in the basic, untenable chemistry of the nation. Cubans still cannot express themselves without fear of punishment or leave their country freely; there is still no free press, and the government remains rabid in cracking down on dissidents. Owning DVD players and cell phones is now allowed, yet precious few can afford such luxuries.

The reason is this: In an attempt to revive the economy during the Special Period, the government legalized the use of dollars, and then set up a whole network of stores to sell Cubans everyday goods—at US prices. This has created a reality that for ordinary citizens simply does not compute: Cubans earn an average of 250 to 300 Cuban pesos, or $10 to $12 a month. Doctors, teachers, and custodians alike. But once their monthly rations run out, usually after two weeks, they must buy almost everything—food, toiletries, clothes—with a dollarlike currency, the CUC, or Cuban convertible peso. On a $10 monthly salary, a $200 cell phone looks like reform only from the outside.

The problem is exacerbated by the scarcity typical of many Third World countries and by Cuba’s stubborn belief that they do not belong to the Third World. They have been taught, in part by a stellar free educational system, to believe in Cuban exceptionalism and told to accept no limits on their potential. (Historian Luis Aguilar León, a classmate of Fidel and Raúl, once wrote, “The Cubans are the chosen people . . . chosen by themselves. They pass among lesser peoples like a ghost passing over water.”) Yet real life is an elaborate game of personal economics: always calculating spending and earning, hustling to accrue capital, parceling out cash on carefully selected purchases, and then calculating all over again. If Cubans chance upon some windfall, they splurge—on toilet paper, shampoo, tomato sauce—because who knows what tomorrow will bring? “Tú no sabes,” Mirta tells me. “You don’t know.” She pauses, her gaze on me, forceful, pleading. “You don’t want to know.”

When I leave Mirta’s apartment, she insists on walking with me a few blocks. As she navigates the narrow commercial street, she stops in front of every store, every street peddler. She may not have money, but in a country where you never know if you’ll find an item from one day to the next, everyone has developed the habit of memorizing store inventories. Mirta glances at flats of eggs set out in the heat on the sidewalk, asks a woman the price for her dulce de leche sweets, and calls out to a young man in fancy jeans carrying blue plastic buckets, “Where did you buy the buckets?” When he tells her that he’ll sell her one for CUC$4, or half of her monthly pension, Mirta turns on her heels.

We pass a crowd peering into the show windows of a state-run department store. On display are pale-skinned mannequins in bikinis, household appliances from China, and a tower of individually wrapped bars of soap. Everything is sold in CUCs, all profits going to the government. Most people linger outside staring, with dejection and longing, at all the things they’d buy if only they had the cash.

As we cross the street, I look back and see that the government has named the store Yumurí. But Mirta has not found her escape through death. Instead, like countless others across the island, she has found respite from her frustration: Tonight, just before bed, Mirta will slip a white pill into her mouth and wait for the sweet oblivion of sleep.

To reach Centro Habana, where Mirta lives, you must head east from the middle-class neighborhood of Vedado, away from its quiet tree-lined streets graced with ocean breezes and decaying villas, or west from photogenic Old Havana, where the benefits of government attention and tourist dollars shine in its restored colonial facades and in the gold teeth of its residents. Centro Habana boasts neither greenery nor fresh paint. Once the site of one of the island’s first sugarcane fields, it is now a stifling maze of narrow streets. The ribbons of sidewalk are so thin that residents must walk single file past the jumble of decomposing neoclassical treasures, high-ceilinged colonial homes out of place in this century, art deco apartment complexes, and Soviet-style block constructions. Some walk in the middle of the street, sidestepping fetid puddles, rotting piles of beans and fruit, and dog feces. Grandparents and small children thread through the streets; young men sip from paper boxes of rum and call out insults to their friends.

Just a few blocks from Mirta’s apartment is the Malecón, which once drew her nightly with its promise of fresh air. These days, however, Mirta stays home and takes her pill instead, overrun as the Malecón is with kids drinking and blasting the low boom-boom-boom of their vulgar reggaeton, desperate to escape their own cramped, sweltering homes. Most habaneros avoid Centro Habana at this hour, when few blocks are lit by streetlamps, and there is a lawless, carnivalesque tinge to the darkness.

One afternoon, Mirta sits down on her rocking chair and tells me about a girl who was killed down the street a few days before. Out of the sky, a rickety cement balcony fell to the ground, crushing the girl. This was not the first such death Mirta has heard of in the neighborhood, and she tells me to check out the balcony two doors down when I leave: even with a wooden splint it is barely held aloft. “You go around the city and it looks like a war zone,” she scowls, “everything falling down, everything crumbling.” Of course, she says, word of the death only circulated in whispers, never in the government papers. “Here all the news is good news. Nothing bad happens here.”

Fueling Mirta’s melancholy are memories of her other reality: childhood in a small city in the middle of the island, one of those provincial outposts with rows and rows of one-story colonial houses spreading out from a central plaza. There were plenty of activities for young people then—social clubs, concerts on the plaza, parties at friends’ houses—not like today, when a can of soda is a luxury, and few Cubans can offer visitors more than a cup of coffee. In the late 1950s, Mirta’s parents were comfortably middle class. They owned a store and sent Mirta to Catholic school. Then, when she was ten, her school was taken over by the new revolutionary government. This greatly displeased her father, who, having emigrated from Spain as a child, was opposed to his only daughter mixing with boys; and after an initial burst of enthusiasm, he grew distrustful of the new government.

During the 1960s, much of Cuban society was either aghast over the loss of capitalism or energized by the revolution’s social projects: nationalization of private industry, rural literacy brigades, and the ambitious undertaking of providing free health care and education to all. While this brought rupture to Mirta’s family, many less fortunate Cubans were finally lifted out of acute poverty. After Fidel’s 1961 declaration that his prodemocracy revolution had gone socialist—and the subsequent American trade embargo—Cuba became intimately dependent on commerce with the Communist bloc. By the late 1970s and 1980s, Cuba, and Mirta’s own young family, was in a golden age: stores overflowed with affordable Eastern European goods, Cuban salaries were worth something, and Mirta and her husband, Gilberto, could take their two girls on beach vacations every summer.

Mirta’s success came, in part, from her father’s trepidation and immigrant intuition for planning. When the call came for business owners to turn over their property in the early 1960s, he relinquished his store for a bit of cash and a pension, and then successfully avoided working for the government the rest of his life. His own cattle were confiscated, but his brothers let him sell milk and cheese from their cows—enough, in fact, to covertly buy plots of land for all five of his children.

“He had a vision of how things were going to go down,” Mirta says, proud but regretful. “All of this”—Cuban code for the system—“he saw it coming,” and he urged his children to participate in the new system as little as possible. Later, as Mirta and Gilberto’s two daughters grew, they taught them the same lesson: stay on the good side of your teachers and peers, so they can’t say you are antirevolutionary, but don’t sell yourself out and join the Communist Youth. “We don’t speak badly about the revolution,” Mirta says pointedly. “But we do not speak well of the revolution.”

When she tires of talking, although it is still too hot to want to move, Mirta heads to the kitchen for her secret vice—the day’s umpteenth pot of coffee. She stops first in her bedroom, returning with two albums of old snapshots: her husband considerably less tired, Mirta many pounds lighter, and the girls still carefree and smiling. The scratch of metal sounds from the kitchen, where Mirta adds spoonfuls of coarse Cuban sugar to the coffee on the stove, and I flip through sun-bleached images of her two little girls: glamour portraits of her youngest before her friends all fled Cuba, shots of the days at the beach, and baby pictures of Mirta’s only grandson, who was born just as the country—and Mirta’s life—came crashing down in the Special Period. When there was no money for family photos or new clothes. Or anything, really. When Mirta realized, with a force from which she is still recovering, that all of her father’s efforts still were not enough.

There is something incredibly depressing about these images, about the cheery past Mirta is so eager for me to see. About knowing that she would soon fall into a hopelessly murky future. When Mirta comes back with the coffee, in a fancy china demitasse for me and a plain white cup for herself, she asks me again and again what I think of the photos. If I saw how different they all looked. There is proof, she wants me to know. Proof that she was not imagining it all.

In Havana there is a fog, a palpable malaise. People stare off into space, brows furrowed just slightly, the anger long swallowed and replaced by resignation. This is a look all around you: on packed city buses, in bureaucratic offices, among professors and housewives and manual laborers. For many Cubans, the idea of getting out on a smuggler’s speedboat—which tens of thousands do each year—is worlds better than sitting around waiting for things to change. Two musicians I know once told me the story of sitting on the Malecón together. One, a normally quite logical young woman, shocked her friend when she asked if he thought there might be a way to invent a poison for sharks. Even I, who am not Cuban, have dark, twisted nightmares every time I am on the island—about being held hostage, and imprisonment, and death.

But Mirta has the pill. To forget. The frustration, the impotence, the memories. It is magic, this Mirta knows. A way to take control for once. Just before bed, at the exact moment when she can no longer stand the stress and is almost exhausted enough to sleep, she pops the pill out of its blister pack. And then the relaxation. There is no grogginess, no feelings of being drugged or hungover the next day. A perfect blip in her life, every single night. One minute she is alert and awake, the next minute she is gone. Then in the morning she wakes, somehow refreshed enough to face it all again. This, especially, is the magic.

One day some years ago, Mirta was shopping at a farmers’ market and came across an elderly woman selling the pills. Finding her was one of those opportune coincidences fueling the lower levels of the Cuban black market, forged more through mutual necessity than greed: Mirta needed the pills, and the old woman needed money. But the woman was so afraid of being caught—selling half of her prescribed monthly regimen—that she left Mirta waiting alone at the market to walk several blocks home to get the drugs. Mirta was paralyzed with anxiety. Was she being set up? What would happen if she were caught? When the woman finally returned, Mirta’s relief was temporary. “It’s heartbreaking,” Mirta says. “You know what she needed money for? To buy milk.”

These days, she buys the pills, at twenty-five times the real cost, from a crooked pharmacist. In 2005, Mirta’s friend Alejandro found the supplier, who hand-delivered drugs to workers in Alejandro’s office—sometimes several times a day. (Most pharmacists, including Mirta and Alejandro’s dealer, refused to talk to me, as jail terms for drug dealing are long.) Their supplier’s key to success, Alejandro says, is skewing the market. Instead of selling each blister pack of pills for ten pesos, like other dealers, he sells for five. While he earns less, the pills cost just forty cents, so he still makes scads of cash. His customers—with few pesos to spare—clamor to buy from him.

Considering the free medical system, Cubans are surprisingly well informed about health and keep small dispensaries at home, often of black-market meds. After all, among other scarcities, pharmacies commonly lack the most basic medications. Aspirin, for example, is impossible to find. And with their days full of bureaucratic errand after bureaucratic errand, Cubans prefer to avoid missing work, and losing pay, to wait in another long line for an overworked doctor to write a prescription for a medication likely to be out of stock. One emergency-room doctor who’s seen addicted patients fake convulsions to get sedatives told me point-blank, “In this country, everyone who works in a pharmacy sells medicines.”

Late one Friday afternoon, through a web of contacts, I find a retired pharmacist who agrees to escort me to the Centro Habana pharmacy where he used to work, which, with its dark wood and large floor-to-ceiling doors open to the street, resembles a European apothecary. The tall shelves are lined, but not full, with white medicine boxes bearing stark, 1960s modernist-style designs. The pharmacist on duty, who wears a black spaghetti-strap tank top and repeatedly wipes perspiration from her face, stands behind the counter dividing the small entryway from the drug display area. She does not sell drugs illegally, she says at first.

Gradations of corruption in Havana, however, are subtle; from time to time, she admits after a few minutes, she gets sympathetic doctors to write her several prescriptions of Mirta’s magic pill—which disappears from shelves as soon as a shipment arrives and is thus always out of stock. She then “gives” the pill to patients in need, who repay her with gifts of five pesos here and there. They understand, she says, that with a monthly salary of CUC$15, she’s stuck in the same economic pressure cooker as everyone else.

Mirta and Alejandro’s pill of choice is an addictive sedative called meprobamate—the single most popular drug on the Cuban black market. (Invented in the United States in 1955 as Miltown, it was the first mass-market psychiatric drug and a precursor to Valium and Prozac.) Yet, because so many Cubans drug themselves to escape frustration, there is simply no stigma about this mass sedation. The government publishes no statistics of meprobamate consumption, but nearly every household has a stash. Official numbers do show that, in a country of 11 million people, annual consumption of only three sedatives—including the generic of Valium, which Mirta also still takes, but not meprobamate—is 127 million tablets.

Once we’ve talked for some time, the pharmacist confides that all her coworkers sell meprobamate, too, although they never know beforehand when a shipment will arrive. This is just one government tactic to deal with the trade in black-market drugs: prescriptions are also only valid for one week, but patients and pharmacists forge prescriptions with new dates; for a time, patients could only fill prescriptions at their local pharmacy, but enough patients complained about the lack of medicines in stock in their neighborhoods that this, too, was scrapped; the government has television campaigns on the dangers of self-medication, but the only segment on meprobamate deals not with an average pill-a-night user, but an addict who takes ten pills at once; and in the first five months of 2005, the military busted 309 black-market sales, according to the government magazine Bohemia, yet Bohemia’s own survey found that more than 50 percent of Cubans buy black-market drugs. If half of Cubans will admit this to the government media, one can only imagine what the true statistics might be.

After days of talking about mental health and black-market meds, one afternoon Mirta stops me midconversation. She can tell from my questioning that Cuba’s passion for sedatives is something of an anomaly. Do Americans take sleeping pills? she asks. I do not want to offend her, and say carefully that it isn’t as common there, and is stigmatized by the stereotype of unhappy housewives downing bottles of Valium. Mirta laughs. The possibility of falling over the precipice is all around her—almost everyone she knows takes sedatives. “Because people know that they have to get up and start all over again. This has been going on for so long here in Cuba that if someone doesn’t take sleeping pills, that’s abnormal.” Both she and Alejandro are uneasy about their underground pharmacist’s corruption in profiting off people like them. But they keep buying.

The more I talk with health workers and Cubans hooked on sedatives, the more I am convinced that the government has strategic reasons for making meprobamate available primarily on the black market. With no aboveground market or statistics, who knows how many tablets are produced or how many Cubans consume them? If meprobamate were conveniently available in pharmacies—and more affordable than on the black market—how many more Cubans would rush to drug themselves? And, the question ultimately is, how afraid is Havana of its citizens unsedated?

As the sun is beginning to set one oppressively hot afternoon, Mirta’s friend Alejandro and I stop at an ice-cream shop near his house after he gets off work. (Almost everyone else is on vacation in August, but Alejandro prefers his air-conditioned office to the one-room apartment he has shared with his parents all forty-one years of his life.) There is a spiffy new double high-rise towering over the ice-cream shop, which neighbors jokingly call Fame and Applause, for the government-paid athletes and musicians living there; in the distance is the José Martí monument at the Plaza de la Revolución. Inside the shop the air-conditioning is bracing, and a dozen men pack the tables drinking beer. Not a single person is eating ice cream. We finally find a seat outside, under an awning and a cluster of palm trees. Although it is nearing evening, the air is still broiling, and Alejandro’s ruddy face drips lines of sweat. With his short black hair and olive coloring, his complexion is what Cubans call trigueño. He has a sturdy build but a serious, nervous temperament that makes him seem often a bit ill at ease. We order mugs of strong, dark Bucanero. At $1.25, the beer costs a tenth of an average monthly salary, and quickly becomes lukewarm in the heat. I am buying, and by the time I’m halfway through my beer, Alejandro is finishing his second.

As he lights up a cigarette, Alejandro tells a story he will come back to again and again. For Mirta, her disenchantment stems from the loss of her girlhood world; for Alejandro it all comes down to the night during the Special Period when he stayed up late watching TV and got so hungry he couldn’t take it anymore. This is what it has come to? he thought, tearing into part of his bread ration for the next day even as he knew that, with just half a tiny roll left for breakfast, he’d suffer tomorrow. Amazingly, Alejandro tells me, he was more optimistic about Cuba’s future, and his own, in the Special Period than today. Everyone complained so vehemently, agitated as they were by that cocktail of heat and hunger, that change felt inevitable. “You could see it in people’s faces. You could see it in the street—that effervescence. It has never come back,” he says. “Now I can eat better. But I don’t have the hope of things changing.”

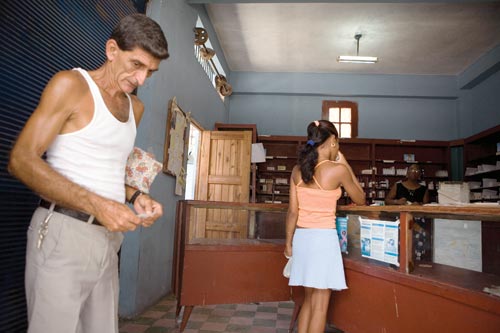

- Customers wait in line to fill prescriptions at a pharmacy. Shortages are a constant reality in Havana.

Complete disillusionment was gradual, but Alejandro’s first crisis came in 1992. In August. He was active in the Catholic Church—although Cuba had been officially atheist for forty years—and his priest had organized a trip to Spain for a small group of young parishioners. Traveling outside Cuba is an incredible luxury, but during the Special Period this was like being transported to an all-inclusive resort—in heaven. Without telling the priest, Alejandro and the rest made a pact to defect in Spain and head to the United States. “We were reactionaries. We didn’t like any of this,” he says—that code again. Four months before the August trip, the priest died. The trip was canceled. The next August, Alejandro checked himself into a psychiatric hospital.

Life had lost meaning, he says, the early evening still overwhelmingly hot as he starts on his third beer. He hated his warehouse job, had nonstop insomnia, and was gripped by an anxious feeling of needing to do something, urgently, although he didn’t know what. He so deteriorated that he had to stop working, and the government gave him two weeks off and free psychiatric treatment. With time and a certain level of resignation, the anxiety lessened and Alejandro worked at going about his life, although he would eventually turn to the pills, just like Mirta. First, however, he tried escaping his cramped apartment—and the fact that all his friends, like Mirta’s daughter’s, had left the country—by going to the movies so often that he became a cinematic encyclopedia. This was slightly better than his childhood, Alejandro says embarrassedly, when he had no TV and depended on neighbors who let him watch. After they went to bed, he’d wander outside, trying to catch sight of a TV set through a window. He’d sit on the street then, watching from afar, until these strangers, too, turned in for the night.

A couple of years after his hospitalization, things started to look up. Alejandro got a job at a nongovernmental organization where his co‑workers shared his politics, and in January 1998, Pope John Paul II was allowed into Cuba, bringing the promise of political transition. Alejandro was convinced change was near; in speeches and conversations with Fidel, the pope pressured the government to loosen restrictions on religion and personal freedoms. But a year later, when Alejandro realized that Cuba was exactly the same as before the pope’s visit, he coped by taking his black-market meprobamate not twice a week, as he’d done for years, but every day. What point would there have been in going to see a psychiatrist again, he says, if they cannot change anything?

“There are no answers,” he says. “And we are stuck griping. Things need to change, but those of us who want change, we don’t do anything. And things don’t change.” Given the danger and futility of going against a dictatorship that has consistently obliterated opposition for half a century, Alejandro does little to protest. His one stab at activism was in 2002, when he signed his name to the Varela Project, an opposition campaign proposing a law of broad democratic political reforms. The Cuban constitution promises the right to propose a law if such a campaign can gather 10,000 signatures, and the Varela Project secured more than 11,000—a major feat, given the political risk to signers. The government, though, responded by ordering a referendum to prove that Cubans were actually in support of more socialism. Not democracy.

The week of the referendum, Alejandro’s parents hounded him constantly to vote the government line, so he stayed out late to avoid them. (The police asked at his work after he signed the Varela Project, and the government monitors voters in elections, which means even abstaining can raise suspicions.) “If they give you the chance to say no, you have to say no,” he says, ranting about a cousin who voted prosocialism just after telling Alejandro, “This is a piece of shit. This is worthless.” In the end, 99 percent of Cubans voted for socialism forever.

At eleven o’clock on a particularly blistering morning, I sip a demitasse of coffee in the Vedado apartment of thirty-five-year-old independent filmmaker Esteban Insausti, whose boyish face is flushed in the heat. Insausti is obsessed with insanity in Cuba—a subject almost as taboo as suicide. I have just watched his polemic documentary on mental illness, They Exist, a film, Insausti says, determined to be “acidic” and “too harsh” by his art school, which attempted to stop him from filming. “It was to try to explain the Cuban reality through the chaos that is insanity—the insanity that we’ve also lived, politically, socially.” Eventually the film was released in Havana’s annual film festival, ending up winning a prestigious award from an international panel, although at the premiere, several police officers were stationed in the theater to prevent a popular uprising. Now digital copies circulate widely on the underground market; one day a neighbor stopped him, Insausti recounts in a stage whisper, saying, “I saw the thing about the locos on the computer yesterday. It was fantastic.”

The flip side to Cuban self-sedation, Insausti reminds me, is the national habit of joking about misfortune. “We add a burlesque, festive tone to almost everything. This has been good in some moments of the reality of this country, because it gives us a capacity for surviving, for assimilating the worst of life. But it’s also horrible.” His film focuses on a mentally ill young man named Manolito, who sings for pesos to adoring habaneros, the twenty-first-century version of Havana’s most famous public loco, the Gentleman from Paris, a bearded old man who wandered the streets, the story goes, after losing his mind in jail during the 1920s for a crime he did not commit. At turns, Manolito can be paranoid or give disarmingly cogent sidewalk lectures haranguing Fidel and the Party—though if anyone else spoke this way in public, they’d be arrested. Manolito and his fellow locos are, it’s clear, both amusement and cautionary tale: in surreal Havana, almost anyone could end up this way.

Yet few know Manolito’s backstory, that he divorced himself from reality at age seven or eight, when his parents left in the 1980 Mariel Boatlift. That was a tumultuous year: Cubans wanting to leave were harassed and beaten in the street, and some committed suicide rather than be called traitors. So Manolito’s parents left without telling him, and in the crossing they both drowned. “People waiting for buses that never arrive, they see Manolito and they know they’ll have half an hour of entertainment,” Insausti says. “I laugh, because it’s crazy. Everything is laughter, everything merits being made fun of, and everything is a good excuse for making jokes. This cannot be, you know? Who are the crazy ones?”

In the morning as I leave my rented room, the heat already overbearing at eight o’clock, I notice a huge pile of trash. The rank mixture of banana peels and food wrappers sits in the middle of the street, just next to an empty dumpster. On the sidewalk two feet away, leaning against a short metal fence, is a print of Fidel from the late 1980s: he’s still virile in his army greens. It is difficult to imagine this artifact ever having been new; the surface of the image is scratched and worn, the once-bright colors of his face and fatigues now pastels of pink and green. The following day, I remember, will be Fidel’s eighty-second birthday.

That afternoon, I am stood up by a psychiatrist whose boss balked at his talking to an American reporter. So I go to see Dr. Jorge Manzanal, a teaching-hospital psychiatrist with more than thirty years of experience and the only Cuban I interview who agrees to be quoted by name. When I arrive at his house in El Cerro, the colonial suburban retreat from pestilent Centro Habana, we sit down on heavy wooden chairs in the high-ceilinged living room. Manzanal, who is light-skinned and bald, sits sweating in jeans and a gray T-shirt with the sleeves cut off. The large shutters are open to the street, and in filters the constant metallic banging of passing 1950s American cars, held together, quite literally, with odd scraps of wire. He doesn’t have much time to talk. Doctors, after all, have to get by, too, and he has errands to run for one of his off-the-record businesses. As we talk, I quickly realize that Manzanal is one of those infinitely rare specimens in Communist Cuba—a person so unperturbed by the idea of persecution that he throws around sensitive terms such as totalitarian regime with such frequency and abandon that I begin to worry who might hear us.

Yet, Manzanal is also a typical Cuban chauvinist and has few critiques of Cuban psychiatry. (The profession has a complicated past, with electroshock still a common treatment, and reports of forced commitment of dissidents as recently as the 1990s, including one deemed schizophrenic because of “delusions that he was a defender of human rights.”) When I’d talked a few days before with another psychiatrist—the department head of a major hospital—he’d put his hand to his neck to show how inundated he was with the depression epidemic, one of the top ten reasons Cubans seek medical treatment, and about which there are no studies, and thus, no statistics. But Manzanal assures me that Cubans are no more depressed than people in the developed world.

He does admit that almost all Cubans want to leave the country. The fact of the matter is that under analogous circumstances—the first few years after Fidel took power—Cubans rushed to psychiatrists in droves. These days, Cubans simply realize that no shrink will be able to solve their problems. And in addition to sedatives, numerous sources (not including Manzanal) agree, alcoholism is common because of taboos that men who take psychiatric drugs are weak. Alejandro, for one, has a cousin who became alcoholic after fighting in the war in Angola (and then simply refused to leave the house for two years), a godfather long addicted to chispa tren or “train spark” moonshine, and a gay friend so tortured by living under a system that once interned homosexuals that he’s taken to filtering the alcohol out of lighter fluid. “We end up at the same thing,” Alejandro told me. “If there aren’t high levels of suicide, there are high levels of alcoholism. Suicide—but on a long-term scale.”

I ask Manzanal about this, and he grows impatient. “I’m not here to help people who don’t have mental disorders,” he says. “This is not an unhappy people. Cubans are happy, even in the midst of misery.”

With that, our conversation is over. I leave suffering from that surreal sensation so common in Cuba—the disorientation that comes from being told, again and again, that things simply are not as they so clearly appear.

When I tell Mirta about my conversations with the psychiatrists, she rocks and listens. Then she scoffs. “They say there is depression all over the world, and that’s true. But that doesn’t take the pressure off of us.” After all, Mirta knows, stress is dangerous.

On the eve of the Special Period, Gilberto was so successful as a mechanic that he and Mirta decided to give their girls the promise of lives in Havana. They moved to a residential neighborhood away from the bustle and grime of the capital’s center, with Mirta battling homesickness. “I started to feel depressed when I left my city. I missed it, I yearned for it.” In time they settled in. Her younger daughter went to university, and the older one started working, moved out, and had a baby. Yet right as Mirta’s grandson arrived, the Soviet Union fell.

Food supplies disappeared. Everyone was stuck with rice and beans for lunch and dinner, and sugar water for breakfast. Mirta was frantic. “I am a very nervous person. What did I do? When there was meat, I gave it to the rest of my family.” By the end of 1991, she was losing weight and fainting; when she finally went to the doctor she was hospitalized with polyneuropathy, extensive inflammatory nerve damage caused by a weakened immune system from malnutrition and a lack of vitamin B. She couldn’t walk for two months, Mirta tells me, bending down slightly in her rocking chair to rub her hands along the fleshy insides of her chronically painful knees. The government did give Mirta leave from her job and free treatment, but she wasn’t alone. An epidemic of the disease swept Cuba from 1991 to 1993, afflicting more than 45,000 people.

Luckily, Gilberto retired from his job and traveled to and from their hometown, where the situation was more dismal but the food cheaper. “We didn’t have that much,” Mirta says, heading to the kitchen to cook. “If I had a piece of meat—one little piece—to give my grandson per day, I felt lucky. For everyone else, it was once a week.” The government, then as now, refused to admit to mistakes, blaming everything on the American embargo. “I don’t know what is worse,” Mirta says, “the information [the government gives us] or the disinformation. I like to inform myself—but with the truth.”

All told, Mirta was ill for three years. This, coupled with watching the suffering around her, sent her tumbling into depression, for which she saw a psychologist and took antidepressants. Now she has devised her own treatment method. Her doctor prescribes meprobamate ostensibly to lower the high blood pressure she developed after moving to Centro Habana a few years ago. (This is a common usage, although the drug isn’t indicated for hypertension.) She buys it in the pharmacy the rare times it’s in stock, and on the black market the rest of the time. “Not everyone who is sick goes to the doctor,” she says. “People don’t want to go to the psychologist, because they don’t want to talk. They go to the psychiatrist, because they want drugs. To be able to sleep.”

Mirta stops cooking, and sits down at the small kitchen table. She turns her head to look out the window, from which only a sliver of blue sky is visible between the gray walls of the surrounding buildings. “You feel static—that you do nothing. Sometimes, I feel despair,” she says. “Especially at noontime.” This is the hour, Mirta says, beginning to cry, when she most thinks of her hometown, where neighbors got together every day for coffee and a card game before lunch. She pretends to call out to her neighbors to come over, as they did then, wiping at her eyes with her palms in large swipes. Most of her old friends have left Cuba, and every time she goes home, Mirta is increasingly distraught by the loss of her world. “Everything depresses me. What I saw, and what I am, and my past.” She does not, however, think of leaving. The government would take her house, the only thing she has.

The last time I see Mirta before leaving Havana, I ask about her future. She rocks in her chair, the friction of wood on tile a metronome of stagnation. “I don’t see any change,” she spits out. “They all talk and talk and nobody does anything at all. I see myself exactly as I am now. Always the same.” She rocks silently, her face contorted in sadness, lips pursed. “I see myself without a future. We are here in the hands of God.”

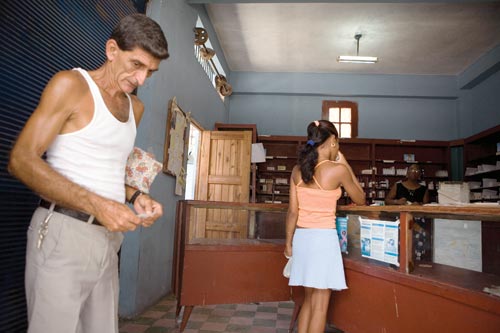

- A woman leaves a Family Care System (SAF) window on a side street in Havana. The program sells food staples to the elderly.

One Saturday night, I get invited to a party in Vedado, in the same building where a thirty-four-year-old Fidel shouted down to crowds of rifle-toting followers that the revolution, his revolution, was now socialist. A block away, I stop to buy beer at a snack bar. Two men are singing for the patrons; one is young, dark-skinned, and obviously drunk. The other, I realize suddenly, is Manolito, wearing thick, goggle-like spectacles and a homemade army-green jacket with too-short sleeves, even in the heat. It is clear that he has aged since Esteban Insausti’s film, and he is now missing several front teeth, but Manolito still looks like a confused overgrown child. Not a contemporary of the dozens of twenty- and thirtysomethings at the party down the street. There, in a darkened kitchen, they pass around the few cans of beer people could afford to bring, and sip from plastic cups of straight rum. They dance, to salsa and American pop, closing their eyes as they twirl and shake, the space heating up by the minute until there is no air left, just asphyxiating steam. The music is too loud to talk, and so they drink, and they dance, and they laugh, and they pretend that they are not here, that they are anywhere else in the world, because isn’t this what young people do?

At this precise hour, too, the reggaetoneros sit along a breezeless Malecón, in a repetition of every other Saturday night, trying to stave off the eventuality of returning to those stifling barrios scattered around the city’s hilly edge. Somewhere in the humid blackness, a single fan spinning against the all-consuming heat, a young woman drifts to sleep, fantasizing about the United States, and the smuggler’s speedboat that someday will transport her there—or to her watery death. On stoops across the city, men drain their bottles of moonshine, glass by glass, in small shows of protest. And at one end of Centro Habana, Alejandro imagines what might be; at the other end Mirta tries to forget. Before bed, they each take one white pill, with its miraculous power to turn the mind blank for the night, hoping that the voyage will be swift.

* Mirta, like most Cubans I spoke with, asked that I not use her real name. ↩

Read “5 Questions for Lygia Navarro,” an interview with the author by Carianne King.