As President Obiang Nguema’s limousine approached the Congresses Palace in Bata, soldiers brandished whippy sticks to part the worthies in green caps and white party T-shirts. For months, officials had been organizing this, ordering tiepins and leather-bound folders, and faxing flowery invitations. This, the ruling party’s third ever congress, was a celebration of Equatorial Guinea’s full-blooded entry into the oil age.

It was July 2001. The American firm Triton was just starting up a big offshore oil field, just fourteen months after discovering it—a world record at such water depths. Mobil was pumping fast from its giant Zafiro field. The government, facing an uncertain future, also wanted to get the oil out fast. “What production profile the government wants . . . is determined by the security of the government,” said Max Birley, vice president of Marathon Oil Equatorial Guinea. “An insecure government will want the oil reserves exhausted as quickly as possible.” By now, Equatorial Guinea’s half a million people already boasted the world’s fourth highest production per capita, more than Saudi Arabia or Iran. Though less than a quarter of the value of Equatorial Guinea’s oil was flowing from the oil companies to the treasury, an exceedingly low share by regional standards, this still meant a flood of money that was already leading to inflation, big salary rises, and what the IMF called “a breakdown in budgetary discipline.”

Kicking off the congress, the planning minister handed me a paper predicting that the economy would grow faster than any other in the world that year: 71 percent, upstaging even the IMF’s dazzling 53 percent forecast. Men in suits and supercilious ladies trooped up to the stage to praise president Obiang and his wife Constancia, the Mother of the Nation. “One man! One woman! One party!” speakers roared, to raised fists and cheering. “This will be the Kuwait of Africa,” yelled one, and the hall erupted. He was mobbed by party cadres like a rock star. Obiang took the podium, softly emphasizing his power. “There is practically no opposition in our land because nearly all political parties, backing the [ruling party], support the same principles.” In the audience, behind impassive diplomats from North Korea, sat a Spanish businessman in dark glasses who seemed to say and do nothing for three days. A big-boned American, Bruce McColm, sat nearby. Two women from the US Congressional Black Caucus, sporting white party neck scarves, raised their fists.

Outside the big hall, watched by Moroccan bodyguards, a lady was shaking her hips and praising “Hermano Militante” Obiang into an overelectrified microphone, as groups of colorful praise singers chanted and slapped their thighs. Farther out, restrained by a low wall and the soldiers, people in tattered shirts and flip-flops stood in dirty brown groups, watching and listening. The chances are that they cannot afford doctors, one in six of their children die before their fifth birthday, and their drinking water tastes of mud.

They were not just missing the bonanza: their lives were being turned upside down. Agriculture’s share of the economy had fallen from two-thirds of the national output a decade earlier, to a twentieth. A cocoa company official said his profits were collapsing, and he was ceding offices to the oil firms. “Oil has worsened the differences between our citizens,” an Equatorial Guinean UN economist, Fernando Abaga, wrote in a paper about the oil boom. “An opulent minority sails in a sea of misery.”

Nevertheless, the mood was very unlike that of the introverted little state I had experienced on my first visit, eight years earlier. Shops were fizzing with French champagne, Japanese televisions, and Spanish fashion, and Malabo was choked with traffic jams and gaudy tropical palaces. In the Pizza Place downtown, oil workers in jumpsuits mingled with Lebanese traders and local military brass, while Cameroonian women in sparkly miniskirts sipped Fanta, watching them all. Light from a giant gas flare on the headland bathed Malabo orange at night.

Obiang was not as brutal as his bloodthirsty uncle Macias, whom he toppled in the 1979 coup. Yet reports by Amnesty International and the US State Department still placed Equatorial Guinea among the world’s most unsavory dictatorships. International narcotics organizations said that Equatorial Guinea’s diplomats used diplomatic bags and other mechanisms to smuggle drugs internationally. In a 1999 book The Criminalization of the State in Africa, three well-known academics concluded that Equatorial Guinea was one of only three states in Africa that could be classified as criminal states. “It’s not even a country; it’s a confusion,” an outraged diplomat said. “A group of people have got hold of this country and are undertaking acts of piracy.”

* * * *

Just ahead of my 2001 trip a Gabonese friend joked about Equatorial Guinea. “Watch out!” he laughed. “The opposition people there have pointy ears.” I knew that Gabon’s silky elites despised their rougher Spanish-speaking neighbors, but I did not immediately appreciate the cruelty of his comment.

In Malabo I met a short, timid man who did indeed have stunted ears. He told me that in January 1998 three soldiers had been killed by ethnic Bubis, the indigenous inhabitants of Bioko Island, who believe that the oil that lies near Bioko Island is theirs, and resent the daily humiliations they suffer at the hands of Obiang’s Fang ethnic group. They had attacked the soldiers with hunting guns and knives, with the vague intention of throwing off the Fang yoke. “They did not have a plan,” my disfigured interlocutor said. “They just wanted the world to know what is happening here.”

Retribution was swift. Soldiers and Fang civilians dragged Bubis from buses and their homes and beat them; some were executed. At police stations men had their shoulders dislocated; women were raped and made to “swim” naked in mud and “show what they did with their husbands.” One woman was told—regarding a fork that had been thrust into her vagina— “from now on, that is your husband.” The man I met said soldiers bound his hands and feet behind his back then cut off the tops of his ears with scissors, before smearing him with sardines and dumping him in stinging ants. Others suffered “la huevera,” a painful torture involving the testicles, or the “hanging bat,” where prisoners’ arms and ankles were tied behind their backs; from these trusses they were then suspended, blindfolded, from hooks. Arms break from the strain. Some men needed help urinating afterward because they could not use their hands. About 500 people were arrested; 15 were sentenced to death, and 70 got prison terms of up to 26 years for “terrorism” and “undermining state security.” Some sentences were commuted, but a few prisoners died in jail after what Amnesty International said was prolonged torture. The government said the mutilated ears—there were several cases—were birth defects.

The Bubis lie on the outermost ring of concentric circles of power here. At the center sits the president; next is his close family, then his subclan, then his Esangui clan from Mongomo (a town south of Bata). The Mongomo clan is part of the larger Fang ethnic group that spills over into neighboring Gabon and Cameroon. Kin relationships are central: some say that when two old Fang meet they can talk for hours to establish their relative places in the ancestral tree, up to ten generations back. Those outside the innermost circles, such as the Fang opposition leader Severo Moto, are mistrusted, and Obiang relies on Moroccans and others for his personal security.

An opposition activist, Juan Nzo, put it simply. “La Familia. There is nobody else.” Others, in private, call them Los Gordos or Los Intocables—The Fat Ones, The Untouchables. “The institutions of state have a phantasmal existence,” said the member of an exiled opposition party. “Everything is manipulated to the will of the dictator.”

The Mongomo clan has kept a tight grip since independence, when Obiang’s uncle Macias took over. Since toppling him in 1979, Obiang has directed bloody purges every eighteen months or so, alleging coup plots that are often (but not always) fabricated.

Placido Micó, a bespectacled, Spanish-trained lawyer who lives above a grubby café in Malabo, spoke vehemently. “Lots of us have been in prison and tortured. They beat us until they run out of energy. They are animals. The people live like rats; without international pressure we would be dead.” He said he’d tried talking to the oil companies, but without success. He was irritated about “Eric the Eel,” a local swimmer who put in a comically slow performance at the Sydney Olympics. “They decorated him for being the worst swimmer in the Olympics. They are making a country of clowns, a society of imbeciles. Instead of recognizing this as a failure of the state to provide swimming facilities, they have concocted a triumph. People are laughing at us.”

Quaint edicts periodically come from on high. A Malabo resident recalled a morning before an African leaders’ summit meeting, when he was woken by a loud banging on his door. It was a government minister who had been told to get their street swept before the dignitaries came. His street was filling with bleary-eyed neighbors with brooms, sweeping. Once, in 2000, half the ministries were relocated from Malabo to the mainland. “In our country, if the minister is not there, the people in the ministry do not work,” a top official told me. “We have to move the ministries, with their ministers, to get the work done [on the mainland].” Obiang is everywhere: on television or on the radio; he looks down from beneath his craggy eyebrows, framed in large portraits that hang in all the offices, which are talismans against bad luck. The charmed few of Malabo can eat out for free, scrawling worthless IOUs to restaurateurs, then melting into the night in air-conditioned vehicles. State media praises him, sometimes a bit too effusively. President Obiang “is like God in heaven. He has all power over men and things,” the radio once said. “He can decide to kill without being called to account and without going to hell because God himself, with whom he is in constant contact, gives him this strength.”

|

| President Obiang Nguema of Equitorial Guinea (Equitorial Guinea government website). |

Yet Obiang is weak in other ways. A foreign businessman remembers how hard it was to get a proposal for a joint venture with Obiang through the cabinet, or Council of Ministers. “With the council of ministers everyone has a say. It has to be unanimous. If you disagree, there is no decision. It took us three meetings to get our center created,” he said. “The council of ministers is really a set of different political bases, and each brings something to the table. Obiang has to weigh whether to alienate a base or not. And often he cannot. . . . They call him the ‘Great dictator’—but there are virtually no consequences for a minister disobeying orders. He says: get XYZ done, and a year later nothing happens.” Perhaps, like a playground bully, Obiang is fierce because he is insecure.

Obiang is also a joy to interview. I have met him several times, and each time he seemed unconcerned with political correctness or how his comments might play with a Western audience. He is tallish and slender, with a soft handshake and bushy eyebrows giving the impression of subdued, tired mirth. When he furrows his brow and wrinkles his nose, perhaps in response to an indelicate question, he is like a sensitive grandfather, pressing his hands together at the fingertips and cocking his head, concerned to set the record straight. In an interview in 2002 with a French journalist, I asked him about the Bubi ear-cutting. These stories, he said in fluent French, slowly wagging his finger, were lies made up by his enemies in the Spanish press. “It was a terrorist coup attempt, to kill people in power here and create panic,” he said. “Thanks to the security forces we found out the information.” Then he backtracked. “But there was no torture.” Could we visit Placido Mico, the opposition leader, who was then in prison? He seemed irritated. Wait for the next national festival, he said. That is the time for clemency. He began talking about foreigners, using the French word etrangers, which can also mean outsiders. Such people, he said, cannot be trusted to look after his personal security. We pointed out that he had Moroccans in his bodyguard. “I was talking about etrangers locally, not those from overseas.” So who, I asked, are these outsiders, not from overseas? “I mean people who are not from my family.”

Another time, I asked him why American oil firms had been so successful. “Spain said Equatorial Guinea has no oil. France said Equatorial Guinea has no oil,” he said, suggesting that perhaps he thought their failures represented a conspiracy against him. “Then the Americans came. In under six months they found oil.”

* * * *

In 2002 I watched Obiang campaigning for presidential elections (which he won with 97 percent). Moroccans in jeans with submachine guns lounged in front of the stage while men from the Special Riot Brigade flanked Obiang, who wore a white party T-shirt and neck scarf. The American lobbyist Bruce McColm stood, stony-faced, on the podium behind Obiang, who railed at the political opposition. “I do not believe any of them renounced being Equatorial Guinean citizens,” he said. “If they do not like Equatorial Guinea, they can go overseas.” I stopped a large African American who said he was a businessman, but when I said I was a journalist, he nodded, and walked away. An amiable gent with bad teeth, who was from the information ministry, denied this was a repressive place, citing television pictures of prisoners at the US base in Guantanamo Bay. “Torture, you see,” he cackled, “it is normal everywhere. The alternative? Chaos.”

Praise singers ululated and chanted. “Sí, sí, sí, Papa, oui, oui, oui.” Obiang began to talk about oil. “In the sacred story, when the Egyptian pharaoh had a dream, he said there will be fat cows representing abundance, then thin cows will eat the fat cows, representing hunger,” he said. “Now we have passed the era of the thin cows. We are now in the time of the fat cows—which is our prosperity!”

* * * *

Two months later an article appeared in the Los Angeles Times, saying that ExxonMobil and Amerada Hess had been paying Equatorial Guinea’s oil revenues into government accounts that were effectively controlled by Obiang, at Riggs Bank in Washington.

Riggs had been open for two centuries and had served (in earlier incarnations) the families of Abraham Lincoln, Ulysses Grant, and Dwight Eisenhower. It supplied the gold for the purchase of Alaska from Russia in 1867. At one time, nearly all foreign embassies in the United States, and half of those in London, banked with Riggs, which promised its clients “utmost discretion.” Riggs had provided mortgages on a luxury home owned by Obiang in Maryland, and one in Virginia for his brother Armengol.

The Senate and a federal grand jury began investigating Riggs for possible money laundering, breaching banking regulations, and violating the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act.

Following a call from a senior Senate staffer, Obiang’s lobbyist Bruce McColm wrote to the Riggs account manager for Equatorial Guinea. “He wanted to inform me that . . . everyone knows the allegations about Riggs are nonsense,” McColm quoted the staffer as saying. “The government of Equatorial Guinea must respond quickly with full force to such articles or they will be believed eventually. The government should not count on the oil companies to defend them, because at the first sign of trouble they will run for cover. The Wall Street Journal was thinking about doing a piece. Also, a New York Times reporter has been snooping around.”

The US Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations—the body that had probed Omar Bongo’s millions in Citibank in 1999—set about investigating Riggs for the Equatorial Guinea accounts. They also probed more than 150 accounts held by Saudi officials, to see if Riggs inadvertently provided banking facilities to the September 11, 2001, hijackers. (The investigators only had a mandate to look at this from a policy perspective—to see if certain systems encourage wrongful behavior, and then find ways to improve the system. They are not detectives, mandated to sniff out crimes and punish the perpetrators.)

The subcommittee held hearings in July 2004 and invited officials from Riggs, oil companies, and the government, to testify. By then, the American bank regulator had fined Riggs $25 million over the Equatorial Guinea and Saudi Arabia accounts, the largest ever fine of its kind, and the accounts were closed. The Saudi matters contained “very sensitive issues— security issues,” as someone familiar with the case put it, and were moved from the Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations to the full Senate committee.

Equatorial Guinea had opened its first account at Riggs in 1995, and became Riggs’s largest customer, with balances of around $750 million. Riggs set up sixty accounts and certificates of deposit for Obiang and his family, and for Equatorial Guinean officials and companies. One of these was a shell company owned by Obiang in the Bahamas, whose account took deposits in suitcases of cash in plastic-wrapped bundles, sometimes weighing up to sixty pounds. Money flowed, with help from British and Spanish banks, from the government account to other companies held by his family members, or to companies whose mysterious owners were not revealed. The accounts at Riggs where oil companies paid their dues to Equatorial Guinea had only three authorized signatories: Obiang, his son Gabriel, and his nephew. To withdraw funds, two signatures were needed, one of which had to be Obiang’s. Riggs rarely asked about this money, as money-laundering laws required, even as Parade magazine placed Obiang below Saddam Hussein on a list of the world’s ten worst dictators. “Where is this money coming from?” a Riggs memo wondered in 2001, before answering itself: “Oil—Black Gold—Texas Tea!” Riggs helped arrange financing for ten Eland armored vehicles, and a Riggs employee even siphoned money into his wife’s account.

“It does not take a PhD or a degree in finance or accounting,” Senator Norm Coleman noted at the hearings, “for somebody to think: Hey, you know something? There is something amiss here.”

Riggs appeared to have ignored easily available IMF reports outlining missing oil revenues in 2001, estimated at an eye-popping 10 percent of GDP. I once asked Obiang why the IMF was so critical. “The IMF is a purely political institution,” he said. “They asked us to give them details of the oil receipts in foreign banks. I do not agree that we give this to the IMF. It is a state secret.” (This comment was published in the Economist and elsewhere; later an Equatorial Guinea official told a contact that Obiang said these things “because the journalist was annoying him.”)

Yet Riggs officials had clearly been worried for a while: an earlier Los Angeles Times article had prompted internal bank e-mails attacking the journalist, Ken Silverstein. “The writer seems to have a grudge against the whole world,” he wrote. “Equatorial Guinea has never been a ‘pariah state’ . . . regarding the President of Equatorial Guinea being corrupt, I take exception to that because I know this person quite well. Sir, I wish in due course you will get to know the President of Equatorial Guinea and witness his simplicity first hand.”

Riggs did, in fact, arrange for outsiders to brief its staff about Equatorial Guinea. The man they chose to do this was Bruce McColm, the American I saw standing behind Obiang at the party rally, who had established a telecommunications joint venture in 2000 with Obiang. After reading his report, senior Riggs officials lunched with Obiang, then wrote him a letter offering “the best financial expertise. . . . [T]ogether, we can reinforce your reputation for prudent leadership and administration as you lead Equatorial Guinea into a successful future.” Senator Carl Levin read this letter out at the hearings, and asked, “How do you write this stuff to a man as abominable as this guy, and known to be abominable? How do you write—how do you, basically, live with yourself?”

* * * *

The initial Senate investigation focused just on Riggs and its role in money laundering. But as they delved, they ran into another matter. The oil companies.

The American companies had paid money not only into the official oil account, but also to prominent Equatorial Guineans. Amerada Hess paid nearly half a million dollars to a fourteen-year-old relative of Obiang’s to rent office space (though the company said that it inherited the lease when it bought its oil interests from another American oil company in 2001.) ExxonMobil leased property from a company controlled by Obiang’s family, paying rent into an account controlled by Obiang’s wife, Constancia. The same company, Abayak, also paid $2,300 for a 15 percent stake in a very small local fuel distribution business, and it owned a major stake in another company that—in partnership with the US firms Marathon Oil and Noble Energy—held 20 percent in an operation to produce liquefied petroleum gas, plus 10 percent of a methanol plant, the world’s second largest of its kind. In addition, the Senate hearings found that the American firms ChevronTexaco, Devon Energy, and Vanco all paid for local students to study in the United States, many of whom were the children of local officials. (It is not clear whether the companies were aware of the students’ status, and company officials said their oil contracts required them to make these payments.) ExxonMobil also paid for security services provided by Obiang’s brother Armengol. These practices do not infringe the US Foreign Corrupt Practices Act. It seems that American law makes it possible to enter into these kinds of partnerships with foreign officials without it constituting bribery.

The oil companies further argued, with some justification, that so much is owned by the ruling family in Equatorial Guinea that they had no choice but to do business with them. Second, some of them said that they had inherited the ventures from other companies, so were not to blame for them and did not have details about how they were set up. This seems odd, given that oil companies routinely check out potential partners before doing business with them, especially when hundreds of millions of dollars are involved. A senator singled out ExxonMobil for being particularly stingy with facts. One might question how hard it would have been for ExxonMobil to find records of these transactions—not least because the company it inherited the contracts from was Mobil. An ExxonMobil official testified in response that it took the subcommittee’s work “extremely seriously” and said that it had provided thorough and detailed submissions. “We maintain the highest ethical standards, comply with all applicable laws and regulations, and respect local and national cultures.” Officials from other companies said similar things about their companies at the hearings.

John Bennett, the American ambassador to Equatorial Guinea, whom I had met in 1993 just as the oil relationship was beginning, attended the hearings.

“It was about as sad a commentary as one could imagine on US business,” Bennett wrote in an e-mail. “All three [Riggs officials] obfuscated like hell, in my opinion . . . the US government’s bank regulators [who were regulating Riggs] represented a collective disgrace to a professional civil service. ExxonMobil has not been able to file answers to written questions posed by the committee.”

Bennett found it hard to believe that the three companies did not know exactly what they were entering into. “This would have been a fun session—outrageous low comedy—if it were not for the nagging thoughts of [what is going on in Equatorial Guinea.]”

In March 2005 the Department of Justice, after its own probe, fined Riggs a further $16 million for failing to prevent money laundering, making the bank the third ever financial institution to be convicted of a criminal violation of the United States’ Bank Secrecy Act. Riggs was then purchased by Pittsburgh-based PNC Financial Services Group for about $650 million.

For his part, Obiang responded in characteristically idiosyncratic style. “If there is diversion of funds, I am responsible. That’s why I am 100 percent sure of all the revenue, because the one who signs is me,” he said in an interview. Later, he added this: “Corruption was unknown in our tradition before . . . bad habits have been introduced by foreigners since oil was found. That is why I am obliged to assume the role of sole national paymaster-general . . . so I can exercise the necessary control.” Government officials also said that Equatorial Guinea’s money was parked offshore partly because the Treasury building in Malabo was not very secure. Sending the money offshore also probably reflects Obiang’s desire to protect “his” money from those around him, keen to get access to the oil money.

Many people believe that offshore skulduggery happens only in places like the Cayman or Channel islands. This is wrong: from other countries’ perspectives, the United States, London, and other places with supposedly clean financial sectors are themselves offshore centers, using bank secrecy to hide and protect money that flows there. The United States is the biggest tax haven of them all, and a delight for foreign dictators.

* * * *

American oil companies and their friends have glossed over Obiang’s ways. Brian Maxted, Amerada Hess’s senior vice president of global exploration, described the government officials his company dealt with as “ethical . . . a breath of fresh air. This might just be the country in Africa that gets it right.” Chester Norris, a former American ambassador to Equatorial Guinea (Malabo has a Chester E. Norris Jr. Avenue), said that Obiang “really wants to bring about democracy and improve the human rights record . . . it’s already pretty good.” Before the Riggs scandal blew up, the US-based Corporate Council on Africa (CCA), an industry association, published a 54-page guide to Equatorial Guinea with pictures of beaming children, water pumps, canoes in the sunset, the American flag, and oil rigs. It says that Obiang’s government “has taken significant measures to encourage political diversity and address human and worker rights issues,” and has placed a “special focus” on transparency. The CCA listed as its sponsors ExxonMobil, ChevronTexaco, and AfricaGlobal Partners—a company with a contract to help Obiang with “investment promotion and political interaction” with the US government.

Other links exist between US politics and the American oil interests in Equatorial Guinea, beyond the well-known friendships that ExxonMobil enjoys in the administration of George W. Bush. Tom Hicks, chairman of Dallas-based Triton, bought the Texas Rangers from Bush and his partners in 1998, and according to the Center for Public Integrity in 2000, Hicks and employees of his companies were Bush’s fourth-largest career patron, having given him at least $290,000. Shortly after Triton was bought by Amerada Hess for $3.2 billion, Triton’s president Jim Musselman added a boost: “Knock on wood, this country is stable and the president is sincerely trying to improve things. It’s not going to turn into suburban Washington, but it could be a model for this part of the world.”

The ubiquitous Bruce McColm is a former president of the International Republican Institute and a former director of Freedom House, and, later, a co-chair of the Iran Policy Committee. He ran two organizations with the initials IDS: one, the Virginia-based Institute for Democratic Strategies, a nonprofit group committed to strengthening democratic processes abroad, and International Decision Strategies, a for-profit organization that set up a telecom joint venture with Obiang. The institute, which received support from Mobil, monitored elections in 2000 and reported them as generally free and fair. The ruling party won 95 percent of the seats. Other observers said those polls were a farce. (To be fair, McColm is a more complex figure than perhaps I’ve painted. While obviously looking after his own interests, he may well have been a force for good, too. Having got into a position where Obiang listens to him, he has been a useful conduit for Western concerns about human rights abuses and a proponent of greater openness.) In an earlier poll in 1996, soon after Mobil struck its huge Zafiro field, I watched soldiers order citizens, lined up and called out by name, to select voting slips from the pile with Obiang’s name on them, and put them in the ballot box. Later, Chip Carter, the son of the former US president Jimmy Carter, appeared on television. He said he was in town on a private visit (unconnected to his father’s well-regarded Carter Center). “I came here to observe the elections and to see some old friends,” he said. “I think the election was transparent and the people were voting with their convictions. It went very well, according to the will of the people.” Obiang won with 99 percent. With another journalist, I went to try and find Chip in a building near the presidency where he was staying. A door opened to the sight of chandeliers and marble, and a dapper manservant with dinner jacket and white gloves. “Mr. Carter,” he informed us, “has gone fishing with the president.”

* * * *

The opposition leader Placido Mico said the thuggery of years past has abated a bit in Malabo, where expatriates live and where human rights groups monitor most keenly—and lobbyists like McColm may even have helped persuade Obiang that human rights abuses damage his interests. In the countryside, however, away from foreign eyes, Placido reckons things are as bad as ever.

As Equatorial Guinea’s income rose from $368 per capita in 1990 to over $2,000 in 2000, the country slipped ten places down the United Nations’ Human Development ranking. It now has the dubious distinction of being the country with the greatest negative difference—93 places—between its ranking in terms of human welfare and its income per capita. Agriculture and manufacturing have fallen to less than 2 percent of GDP between them, while oil claims 93 percent. The share of health and education spending has shrunk.

Obiang said in 2003 that there is no poverty, only “shortages.” Yet the IMF in 2005 was gloomier. “Unfortunately,” it said, “the country’s oil and gas wealth has not yet led to a measurable improvement in living conditions for the majority.”

Now, despite all the scandals, powerful Americans line up to praise Obiang. “He came asking for our technical assistance,” World Bank president Paul Wolfowitz said in 2005, “so they can manage their newfound wealth, manage it—[applause]—manage it according to the standards of transparency and accountability that will ensure that wealth goes to benefit the people. . . . I was very impressed at his leadership.” US AID has signed an MoU with Equatorial Guinea that, it says, “will serve as a model for future partnerships.” President George W. Bush in May 2006 directed the secretary of defense to begin a new military partnership with Equatorial Guinea.

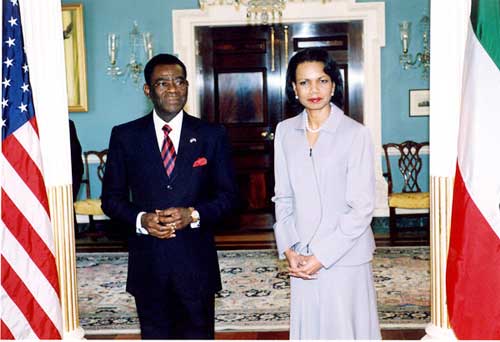

US secretary of state Condoleezza Rice meeting with President Obiang in Washington, DC, April 12, 2006 (US State Department photo).

“You are a good friend and we welcome you,” gushed US secretary of state Condoleezza Rice at a press conference for Obiang in Washington in April 2006 (his visit followed George W. Bush’s presidential proclamation in 2004 barring corrupt foreign officials from entering the United States). A spokesman for Obiang was just as effusive, “The United States has no greater friend in central Africa than Equatorial Guinea.” Senator Carl Levin took a different view of Ms. Rice’s meeting. “The photograph of you and Mr. Obiang,” he told Rice, “will be used by critics of the United States to argue that we are not serious about human rights and democratic reforms.”

Back in Equatorial Guinea, just like in Angola’s Cabinda province, the American oil workers live isolated from the rest of the country in places like Marathon’s Punta Europa complex, a haven carved out of Malabo’s chaos. Oil workers call it Pleasantville, and it comes with wi-fi internet, direct dialing to the United States, regular power and water supplies, hospitals and supermarkets. They are building a liquefied natural gas plant nearby, whose gas will be flowing into British homes from late 2007.

“This is the shit-hole of the planet,” an American oil worker told a journalist from Der Spiegel magazine who visited Equatorial Guinea disguised as a priest. “Our bosses hate the corruption, they hate these guys and most of all they hate the protocol. They’re oil titans who have more people working for them than this place has residents. They fly in from Houston in their Lear jets. When they get here, they meet with a minister who decides to cancel the negotiations if anyone dares to sit down before he does or neglects to call him Excelentissimo. . . . The Texans know, of course, that their business partner sitting across the table is no ‘Excellency,’ but in truth a ‘son of a bitch.’ Deep in their hearts, they despise themselves. Both sides despise themselves. And each side knows that this is true of the other.”

I wonder how much good can come out of a relationship like this. I would not necessarily argue against engaging with Equatorial Guinea, if the aim is to improve matters for ordinary people. Even so, Obiang’s boosters take things a bit far, reinforcing a suspicion that any behavior can be ignored in the pursuit of oil. “I think there’s a sincere intention on the part of the president,” said Marathon Oil’s president Clarence Cazalot, “that they really be the model for the way it should be done.”

Maybe the oil companies’ spin doctors actually believe their own words. “In Equatorial Guinea, ExxonMobil is making a difference,” the company said in a statement. “Being a caring neighbor takes many forms. Sometimes it requires muscle as well as financial support. And sometimes it just requires the initiative of one of the world’s premier companies, simply because it is what caring neighbors do.”