The first time I heard a woman describe her time in Iraq in glowing terms, I was taken aback. Marine Colonel Jenny Holbert told me that being in charge of public affairs for the second battle of Fallujah was “probably one of the biggest events of my life, other than birthing two children.” Colonel Holbert’s enthusiasm for deployment was only one of many surprises I encountered over the course of conducting forty-six interviews with women soldiers, sailors, and marines across the eastern seaboard—a small portion of which are presented here.

Photographer Sascha Pflaeging and I conceived of our collaboration as a way of hearing the stories and showing the faces of some of the first large cohort of women—over 180,000 as of this writing—who had served in the American military in combat zones. Though male soldiers have long been the subjects of documentary photographs and oral history interviews, it is rare that women have had a chance to relate their experience of combat. If we listen to them, these women—these mothers and wives, these soldiers and veterans—will unsettle our fixed ideas about Americans at war and add dimension to the often flawed or fragmentary pop culture depictions of women in the military: as novelties, but not as real soldiers.

The women I interviewed upset any number of cultural expectations of women—none more than the notion that motherhood should be the driving force in any woman’s life. Marine Sergeant Jocelyn Proano said, “You want to be a marine, you can’t be a mom all the time.” Sergeant Proano, who joined the military after being expelled from high school, talked about getting her deployment orders when her daughter had just turned one. “That was the worst ever—to leave my kid,” she said, yet Proano ended up extending her six-month deployment so that she wouldn’t have to leave her unit.

Not all women I interviewed celebrated this shift in importance from family to unit. Many women were disturbed by the way their deployments had attenuated the bonds with their children. Army Staff Sergeant Connica McFadden deployed with her husband when she was still breastfeeding their six-month-old. They returned a year later to find that their daughter did not recognize them—and cried when left alone with them. Yet even as military life made motherhood difficult, motherhood was the reason many women gave for joining the armed services. Several women I interviewed had children with serious health problems; for them joining the military was a way of getting good health insurance, of caring for their families.

Motherhood for deployed women is even more complex than these stories suggest. Dr. Lori Sweeney, a retired major in the Army, told me that when she was serving in Iraq, she saw women get pregnant in order to cut their deployments short. Since the military prevents doctors from prescribing birth control (a rule Dr. Sweeney ignored), it is likely that not all of these pregnancies are deliberate—especially because of the stigma attached. “When soldiers become pregnant and it occurred during deployment, it’s actually punishable,” Sweeney said, “a military punishable infraction.” (Because I was interviewing active-duty military personnel, I could not bring up “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell”—though more than once a woman’s girlfriend was present during the interview or joined us afterward.) In part, rules against sex in theater are intended to prevent pregnancies; in part, they are intended to discourage marital infidelity.

After one interview, a veteran of the first Gulf War, now a civilian employee of the Army, described the adultery in her unit. “Of course, it’s not like what goes on today,” she said, “with all those women soldiers prostituting themselves over there.” Unlike previous wars like Vietnam, she explained, there wasn’t a great deal of prostitution by local women in Iraq—and female soldiers and marines were supplementing their meager paychecks by taking over this business. Several women I interviewed confirmed that they had heard these rumors, but Sergeant Proano said, “I heard rumors about some lieutenant with a sea bag full of cash from making booty calls. But you know, I think it’s just another way to trash women in the military.”

The kind of trashing that Sergeant Proano talked about took many forms—including rape and sexual harassment. Army National Guard Sergeant Shyra Jones complained about the curfews at Camp Virginia, where she was stationed in Kuwait, but acknowledged the reason for them: the threat of rape. Army Staff Sergeant Chanda Jackson wondered whether the threat was greatest from the Afghans and Third Country Nationals on her base, or from her fellow GIs. Once in a while a woman would tell me, halfway through the interview, that she had stayed up late the night before, debating whether or not to tell the truth—then would share her story of rape or harassment. Army Staff Sergeant Shawntel Lotson described a CO who made a woman who was being inappropriately touched by a superior officer apologize to the offender for complaining. On the other hand, she told me, another EEO officer for whom she had great respect had punished abusers—but he had burned alive when his vehicle was mortared.

When we began working on this project, I had envisioned interviewing vets who were both pro-war and anti-war. After doing forty-six interviews, I have come to believe those categories are largely irrelevant. Former Army Reserve Captain Lisa Harmon said that when she was deployed, she spent hours on the internet, trying to find positive information about President Bush and about the war effort; otherwise, as a captain in charge of organizing supply convoys with a 10 percent attrition rate, she could not stand looking her soldiers in the eye and sending them out. When we went to interview Army Sergeant First Class Kim Dionne in Maine, she was clearly ambivalent about the war. When we drove up in our SUV—the only vehicle left at the rental agency following a much-delayed flight—she cracked, “So that’s why we’re fighting this war.” Yet she spent a year flying from one FOB to another in Iraq and Afghanistan, signing up soldiers for additional tours of duty.

Colleen Fagan told me that many soldiers, sailors, and marines did not even vote, because thinking about politics made it harder to focus on the mission. Lori Sweeney maintained that her opinions about the war would shift from one extreme to the other during any given day of her deployment—but that she, like so many other women I spoke with, found her strength in her relationships with other members of her unit. Even Sergeant First Class Gwendolyn-Lorene Lawrence, who had endured not only abuse at the hands of a superior officer, but a grueling two-year battle to reverse the disciplinary action she faced, had not lost faith in Army values—the ones which are printed on posters that you can see in any base—loyalty, duty, respect, selfless service, honor, integrity, and personal courage.

In the end, what struck me most about the women I interviewed was their capacity for survival—all the ways they balance their family lives and their lives in the military, the ways they found to keep going after seeing and experiencing horrific things. For these women, the war has been transformative, life-defining, difficult to escape, and almost impossible to understand for someone who is not part of the same cohort. In today’s all-volunteer military, the kinship among those who have deployed is magnified by all the ways in which the military really is a very separate culture from the rest of the United States. My hope is that by seeing the faces of women who have deployed, and hearing their stories, those of us who are outside that world can begin to get a sense of all the ways women are experiencing this long war. And get a sense, as well, of the ways in which their experiences—of military motherhood, of deployment to a combat zone—may ripple out and inflect the experience of all American women.

Sergeant Paigh Bumgarner

Army National Guard (retired)

Deployed to Balad January 2005–January 2006

Worked as a convoy gunner

I spoke with Bumgarner at her apartment in Richmond, VA, in December 2007

We went by this one base called Ashraf, and it wasn’t as busy as it should have been. When there’s not a lot of hustle and bustle, you know something’s up. The first gun truck reported they passed a dead dog on the side, which had an IED in it, and it blew up right behind the first gun truck. Then, a daisy chain of three other IEDs went off, and we started taking fire from the left all the way down, but we had to keep on going to get through, because we can’t break up a convoy, so we just kept going through this fire.

They had RPGs. They were shooting for the tires and the gunners on everything. We had a lot of vehicles get hit with RPGs directly into the windows. Once we got through, they tried to hit us with a VBED [vehicle-borne explosive device], but I ordered, “No one gets close to this convoy.” So that was taken out. It was a confirmed kill, and it was a VBED. They found just an amazing cache of weapons, and there was actually nine more IEDs.

I get in touch with Mulcahy, who was the commander, and he was like, “Um, Bum, I need you back here.” And I was like, “Why?” He goes, “I need the body bag.” And I was like, “For who?” And he was like, “Ski.” My driver just froze, and I was like, “Come on. Just turn around.” I literally had to like talk him through it, because that was his friend, too, and I went back there, and saw Mulcahy and Ghent, who had got shrapnel damage, and I got two medics to go over there and combat medics to help bandage them up and, you know, just be there for them. I looked at him, and I was like, “Where’s Ski?” And I looked in the back, and, you know, there was my buddy, completely in pieces. So, I went and got the body bag, and put him in there, and then this guy came over and he just looked at me, and I was like, “Go get some gloves.” And so, we cleaned up the truck. I wouldn’t let anyone else near. No one needed to see that.

Specialist Elizabeth Sartain

US Army

Deployed to Kuwait January 2007–July 2007

Worked in a Mortuary Affairs unit

I spoke with Sartain at the Army Women’s Museum at Fort Lee, VA, this past March.

I asked the recruiter, “What’s mortuary affairs?” And he said, “I couldn’t even lie to you.” He goes, “You’re only the second person in ten years to ever pick that MOS [Military Occupational Speciality].”

The devastation that we saw was so incredible. And when we went to AIT [Advanced Individual Training] there was only small arms fire. There was no IEDs, so we weren’t really prepared to see what our fallen comrades looked like when they came to us.

When we work on the remains, we go through their personal property. We see letters from their family, pictures, a baby sonogram, and we have to double check to make sure if they have a wedding ring on. I just felt guilty for doing that.

We had some high-profile cases. Back when I was deployed, there were seven soldiers that had disappeared, and it was all on the news, and we only received three out of the seven. You could see how they were tortured alive. And then to see their families on the TV not wanting to believe that this was their child. They still wanted to believe that their child is out there, you know, alive.

When I was over there I became anorexic. I would be so depressed and tired that when it was my day off, I just couldn’t even make it to the chow hall, so I had lost over thirty pounds in six months. Then I started having restless leg syndrome, panic attacks, anxiety attacks. Since I’ve been back, I still have insomnia, nightmares, and now I overeat. I have gained forty pounds since I’ve been back—just from the depression, just constantly feeling like the food is going to make me feel better.

I’m angry. I didn’t have this PTSD before deployment, and it’s a career-ender for me. And then there’s a lot of people that have it and they’re two years away from retirement, so they don’t want to get help. Or they’re up for a promotion, and they don’t want to get help for it. So, they just end up living with it.

Staff Sergeant Jamie Rogers

US Army

Deployed to Camp Liberty South near the Baghdad International Airport, November 2004–November 2005

Worked as MSP patrol and convoy security

I spoke with Rogers in June 2007 at the Army Reserve Training Center in Auburn, ME.

We used to joke that we were outside the wire more than inside. We ran missions mostly at night at first because it’s a lot safer to run convoys at night—because haji, they can’t see you as well—but then it changed and we started twenty-four-hour shifts. So sometimes you would work a twelve-hour patrol in the day or a twelve-hour patrol at night. And twelve hours in a combat zone is just very intense. Very demanding. Not only physically, because you had so much equipment on you, but mentally draining. Because you never knew what was going to happen. Never.

There’s two soldiers that didn’t come home to their families that I knew very, very well. Worked with them day in and day out. And sometimes you feel yourself slipping up and you’re going to your old ways. And you’re like, “Why am I here?” And you got to reflect and say, “This person died so I can do whatever I want. I shouldn’t be acting like this. I shouldn’t be treating someone like this.”

People worry about their jobs, but at night, they go home to their wives and sons and daughters. We don’t. If Uncle Sam says go, we go. We really don’t ask questions. We might complain about it, but we don’t ask questions. And it’s just the gratefulness, I mean. They’re just not grateful at all.

And some people do come up and say, “Thank you,” you know, “I appreciate your service.” But many of them, if they come up to you, they ask you immediately about the war, if you support it, and then they put their opinion in. A service member doesn’t need to hear that. A service member can say, “Thank you. No problem.” And go on. It’s the gratefulness. Not everybody wants to hear your opinion. Sometimes, just keep your mouth shut.

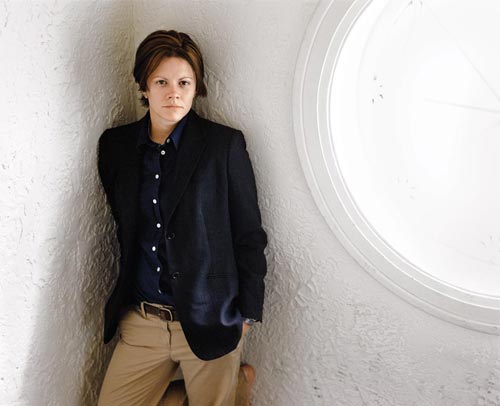

Sergeant Jocelyn Proano

US Marine Corps

Deployed to Al Asad Airbase February 2005–February 2006

Worked on the flight line servicing aircraft

I spoke with Proano last October at the home of Master Gunnery Sergeant Constance Heinz in Jacksonville, NC.

I grew up in New Jersey in the ghetto. I was always getting in trouble—getting into fights. And so I got expelled from school.

My brother was the one who actually inspired me to join the military. He joined the Army and his recruiter said they had a Army challenge youth program and you could get your GED, so I did that and it’s military training in there, so I kind of did the Army boot camp. And I loved it so much— living in a squad bay, going out PTing. It was just awesome—marching and all that. The Army was pretty cool and then I started hearing about the Marines. I just want to go out, get some adventure, travel, go out to war. I just wanted to do the whole nine.

I got married and had a baby. Right then I wanted to be a mom and stay home and then they finally hit me with the deployment. She was a little over one, so … That was the worst ever—to leave my kid. The mommy mentality left me as soon as we got on that bus. All of a sudden the Marine hit me and I’m like, “All right we’ve got combat training.”

I called my mom every day—“Hey, how’s the baby, what is she doing?” I think that the most emotional part was she wasn’t walking and talking when I left and all of a sudden, she’s babbling “Mamma.” I cried on the phone when I heard her talk—it was sad, but it was so amazing at the same time.

I liked being out there. Because when you’re out there, who cares, you’re at war. Who cares if you don’t have your boots laced up the way you’re supposed to or you don’t have a good haircut. You come home and they’re shooting you with all these regulations again.

I need to get out of here, because now I’m sitting back in the office doing paperwork. I’m not out there doing all that cool stuff. So I’m actually trying to get out of there and trying to deploy again. Even though my mom’s like, you know, you don’t want to leave your daughter again. That’s kind of hard to juggle. You want to be a Marine, and you can’t be a mom all the time.

Major Lori Sweeney

US Army (retired)

Deployed primarily to Camp Bucca, near Basra, from February 2004–February 2005

Worked as the camp physician

I spoke with Sweeney in January 2008 in her office at the Virginia Commonwealth University Medical Center in Richmond.

So the press hit about Abu Ghraib and as a result of that, about 1,000 to 1,500 prisoners were brought to Camp Bucca.

I had this really interesting experience of working with this surgeon who had been the personal surgeon to Saddam at one point, who was not this die-hard Saddam loyalist, but who had happened to just be caught up in all of this, who was a prisoner. But they allowed him to do surgery because the need was so great while we were there, and the wonderful thing was that he got me quickly trained on simple suturing and things that I was not real prepared to do, because I had been an internal medicine doc—chronic illness, ICU doc—that didn’t do a lot of suturing and a lot of small surgical procedures.

He was a terrific guy, and before I left Bucca, he had actually been freed, but they allowed him to sort of live in the aid tent, so he was not part of the general population as kind of a gift back to him for all of his service. But he, bless his heart, probably did six hundred small surgeries while I was there and helped to train me and my medics. Iraq used to be state of the art medicine and then, because of all the turbulence, really fell behind, so that they were really ten years behind the power curve.

He talked about Iraq ten years ago, fifteen years ago, and the irony that fifteen years ago the major medical problem in Iraq was Type 2 Diabetes because the culture lived so well. He talked about the romantic Iraq of fifteen years ago and what it was like to come up through training. But mostly he wanted to talk about medicine. You could tell he was one of those guys who probably had fifteen medical journals, that he read all the time. It was like he was starved for information. So, a lot of what we talked about was what was new and exciting in medicine, and we were colleagues.

Staff Sergeant Shawntel Lotson

US Army

Deployed near Baghdad from April 2003–April 2004, and Camp Taji from February 2005–February 2006

Worked repairing construction equipment and in corrections at Camp Taji

I spoke with Lotson at the Army Women’s Museum at Fort Lee, VA, in December 2007.

You have to go through the correctional training. It was about a weeklong training; you have to learn how to handcuff the detainees, how to search them, tell them what to do, how to touch them, how not to touch them. Then once I got out there, it was twelve hours on, twelve hours off—which was actually about fourteen hours, because you have to make sure that the soldiers are up and ready. But being out there, I was also the evidence NCO, so you saw a lot of different terrorists that came through there from different countries. And they also bring in the minors. If they’re with their family members, they bring the minors in also. The mother instinct kind of comes out, but at the same time—hey, look—these people are trying to blow you up. But that mother instinct comes in because you have the child crying, “I want to be with my father. I want to be with my father.” But, you can’t.

You have detainees that come through that are so scared, too, because they don’t know what’s going to happen to them because they got caught. And it’s kind of like, “You know what? We’re here to do our job. You were brought here because you were trying to do your job.”

If you see a soldier who might yell at a detainee or kind of nudge them along— “You’re moving too slow”—you kind of have to say, “Hey, look, I don’t want to be the next person on CNN, so don’t touch that detainee.” You have those soldiers who are just so angry and so upset and so passionate about the terrorists that are trying to blow us up that they want to fight. Yes, we know they’re our enemy, but at the same time, we have to treat them humane, so that we don’t get ourselves in trouble. So, it was kind of hard, and there were times when I wanted to choke a few of them, but you know, you can’t.