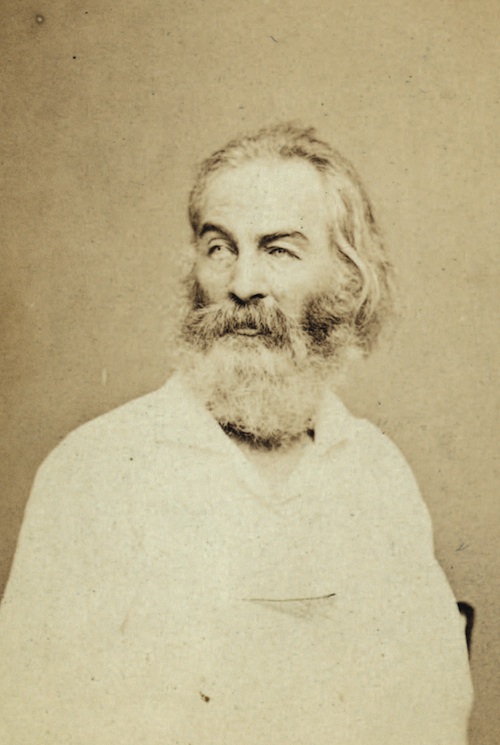

On Tuesday, December 16, the New York Herald printed a list of soldiers killed or wounded at Fredericksburg, including an entry for “First Lieutenant G. W. Whitmore, Company D,” of the 51st New York Infantry. It was mid-morning when poet Walt Whitman saw the item and surmised that it referred to his brother George. In a fevered hour, Walt informed his family and made arrangements to leave New York for Washington, DC, where the wounded were being transported.

Pick-pocketed on the ferry along the way, Walt arrived in Washington “without a dime.” With the help of his former publisher Charley Eldridge, by then working in the office of the Paymaster General, Walt spent the next day “hunting through the hospitals, walking all day and night, unable to ride, trying to get information, trying to get access to big people.” Walt’s brother Jeff back in Brooklyn saw in the New York Times that George was now listed under his correct name with a wound to his “face.” He wrote immediately with this news to Walt, telling him, “we are trying to comfort ourselves with hope that it may not be a serious hurt.” Meanwhile, Walt had concluded that George must still be in camp near Fredericksburg and began working bureaucratic channels to obtain a pass.

It was Friday afternoon when he arrived at Falmouth and made his way to Ferrero’s brigade. “When I found dear brother George, and found that he was alive and well,” Walt wrote his mother, “O you may imagine how trifling all my little cares and difficulties seemed—they vanished into nothing.” George had sustained a deep gash from a shell fragment—”you could stick a splint through into the mouth,” Walt wrote—but the wound had not been deemed serious enough for him to be confined to the hospital. Walt sent the good news to Washington via messenger to be telegraphed home to Brooklyn.

Whitman spent the following days visiting the two makeshift hospitals set up in commandeered manor homes along the Rappahannock: the Conway House and the Lacy House. The grand old homes still stand overlooking the river and up toward Marye’s Heights—the former Confederate stronghold and now a national cemetery for the battle-dead. Today, the grounds of the Lacy House are surrounded by manicured lawns and well-tended gardens of hedgerows and flowers. But in 1862, when Whitman arrived at Falmouth, the trees were leaf-bare, and the winter-killed grass had been pounded into a thick muck by the boot-soles of soldiers and the wheels of wagons and field ambulances. In the dooryard of the Lacy House, he witnessed a grisly scene of human carnage:

Out doors, at the foot of a tree, within ten yards of the front of the house, I notice a heap of amputated feet, legs, arms, hands, &c., a full load for a one-horse cart. Several dead bodies lie near, each cover’d with its brown woolen blanket.

Whitman approached three bodies on untended stretchers. In his notebook, he wrote, “Three dead men lying, each with a blanket spread over him—I lift one up and look at the young man’s face, calm and yellow. ‘Tis strange.” Then, almost as an afterthought, he added a parenthetical line directly addressing the young man: “I think this face of yours the face of my dead Christ.” Nearly the entirety of the poem “A Sight in Camp in the Daybreak Grey and Dim” resided in that short entry:

A sight in camp in the day-break grey and dim,

As from my tent I emerge so early, sleepless,

As slow I walk in the cool fresh air, the path near by the hospital-tent,

Three forms I see on stretchers lying, brought out there, untended lying,

Over each the blanket spread, ample brownish woolen blanket,

Grey and heavy blanket, folding, covering all.

Curious, I halt, and silent stand;

Then with light fingers I from the face of the nearest, the first, just lift the

blanket:

Who are you, elderly man so gaunt and grim, with well-grey’d hair, and flesh

all sunken about the eyes?

Who are you, my dear comrade?

Then to the second I step—And who are you, my child and darling?

Who are you, sweet boy, with cheeks yet blooming?

Then to the third—a face nor child, nor old, very calm, as of beautiful yellow-

white ivory:

Young man, I think I know you—I think this face of yours is the face of the

Christ himself;

Dead and divine, and brother of all, and here again he lies.

When Whitman lifted the woolen blankets to look into the faces of the dead, the fear of recognition was potent: he was still thinking of his brother George. But what he sees is not the face of his own brother, but rather “the face of the Christ himself; / Dead and divine, and brother of all.”

That moment of connection—that radical identification with men, young and old, who were otherwise strangers to him—reshaped the rest of Whitman’s life. He resolved, after George returned to active duty, to stay on in the hospitals in Washington, ministering to the soldiers there. The following short essays take measure of the impact of that decision—how Whitman was shaped by the Civil War and, in turn, has greatly shaped our understanding of that pivotal time. They show, too, how Whitman’s poems continue to speak, across time and place, addressing familiar concerns, as our nation once again wearies of years of war and the casualties, both visible and not, that fill the hospital wards of our nation’s capital and scar the soul of our country.