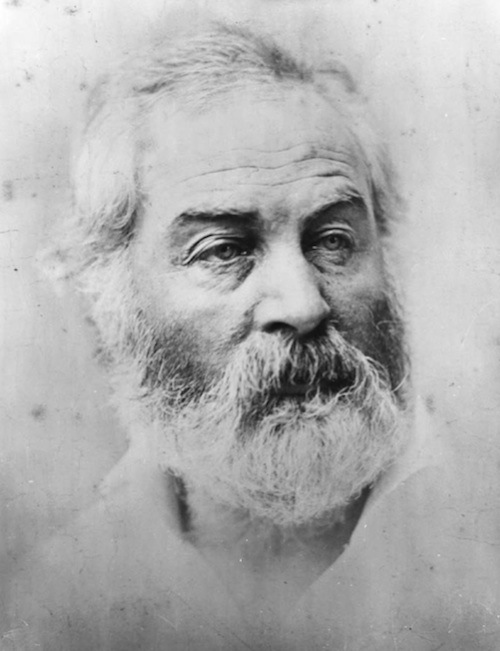

- Walt Whitman, Charles Feinberg Collection, Library of Congress

The day Abraham Lincoln was first elected president, the Prince of Wales (later King Edward VII) arrived in Washington, DC, to find, in the words of a British reporter, a “strange city, whose streets of ill-built houses connect to the most noble public buildings,” or, as an American writer puts it, in the same year, “Washington was merely a place for government. It was an idea set in a wilderness.” If DC, in 1860, was set in a wilderness, it was, worst of all, in itself a bit of a wilderness set in a wilderness. That is to say, it was a swamp, a mud city, a sort of enormous farm lot, a place where pigs and cattle and a few wild things generally roamed freely over the landscape and the “cityscape” and where dysentery and diarrhea were common and where, until the Civil War broke out, saloons and brothels and gambling halls outnumbered anything approaching culture. Yet once the war did break out and brought its carnage home, the low-life establishments were largely replaced by no more or less than tent hospitals, bivouac avenues, crowds of mixed loyalties, piles of body parts, and graves. The pigs and the mud, however, remained.

The Capitol Dome had still to be built and the Washington Monument was only halfway up and resembled a tall factory chimney. And to complement the herds of pigs and cattle, “everywhere hucksters abounded,” writes Margaret Leech in her classic Reveille in Washington: “Fish and oyster peddlers cried their wares and tooted their horns on the corners. Flocks of geese waddled on Pennsylvania Avenue. … People emptied slops and refuse in the gutters.” And Washington was certainly the poor cousin to Philadelphia and New York, older cities to the north, with its limited economy of government clerks, a few farmers, fishermen, bakers, and carpenters, and, by one accounting, in 1860, three veterinarians, six undertakers, a hundred doctors, and, naturally, a hundred-and-eighty lawyers. A provincial capital, a city betwixt and between, Washington, it its way, was a compromise city, with a Southern soul.

Compare it to mid-century, “mast-hemm’d Manhattan,” for instance, and there is no comparison. “I am quite fond,” writes peripatetic poet Walt Whitman, at the early stages of the Civil War, while he is still living in Brooklyn—”I am quite fond of crossing on the Fulton Ferry, or South Ferry, between Brooklyn and New York, on the big handsome boats. They run continually day and night. I know most of the pilots, and I go up on deck and stay as long as I choose. The scene is very curious and full of variety. The shipping along the wharves looks like a forest of bare trees. Then there are all classes of sailing vessels and steamers, some of the most beautiful steamships in the world, going or coming from Europe, or on the California route, all these on the move.” This scene, of course, has already been elevated to transcendent status in “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry” five years earlier. It’s a scene that makes Washington feel like the frontier.

Whitman doesn’t make it to the Washington area until late in 1862, when the city has been relatively transformed from general muck and mess into a more specific yet massive muck and mess of hospitals and encampments. Whitman’s brother George is into his second enlistment in the Brooklyn Regiment of the Army of the Potomac and has just been involved in the Battle of Fredericksburg, less than a good day’s march from Washington. George has not, however, been heard from for a while—and he is an inveterate letter writer—and then Whitman sees a name similar to George’s listed among the wounded in a New York newspaper. Fearing the worst, Whitman makes his way south to see what the story is. After a stopover in Washington, he heads to the expanse of the battlefield and its makeshift hospitals, where, in fact, he does find George wounded, but not seriously.

It is widely assumed that Whitman spent all of his time in Washington, tending the wounded and acting as parental or fraternal patron. And it’s true that most of his ten-year exile from his beloved Brooklyn was spent in Washington, but not all of it and not at the beginning. When Whitman finds George he finds a calling. Once he witnesses the lack of care and the degree of despair among soldiers hardly more than boys, he becomes committed to doing what he can for them, whether through nursing, counseling, or letter-writing for those unable to do it themselves. But it all starts, not in Washington, but on the battlefield, right there in Falmouth, Virginia, outside Fredericksburg, down the road from the original year-old Battle of Bull Run.

“I hurriedly went down to the field of war in Virginia,” he writes on December 13th; on December 21st, he begins “my visits among the camp hospitals of the Army of the Potomac.” And as the December days pass, “spent a good part of the day in a brick mansion on the banks of the Rappahannock, used as a hospital since the battle; seems to have received the worst cases.” One of those days, being the good reporter that he is, he notices, “at the foot of a tree, within ten yards of the front of the house … a heap of amputated feet, legs, arms, etc—a full load for a one-horse cart.” On another day, “several dead bodies lie near, each covered in a brown woolen blanket. In the dooryard, towards the river, are fresh graves, mostly of officers, their names on pieces of barrel staves or broken boards stuck in dirt.” These moments fairly represent what Whitman would see on a daily basis. More than the hard facts, though, is the texture of what he’s experiencing—the flesh and blood of it, the utter ephemeral mortal nature of it, the makeshift quality of absolute mortality. Even when he establishes residence in Washington, he ranges out into the fields of dead and wounded after battle, sometimes following along with the transport of survivors back into the city. He becomes a self-designated nurse and confessor to and for these broken young men. He becomes their aide-de-camp, when he can manage it. “I try to give a word or trifle to every one without exception. … I make regular rounds among them all. I give all kinds of sustenance, blackberries, peaches, lemons & sugar, wines … shirts & all articles of underclothing. … I always give paper, envelopes, stamps. … To many I give (when I have it) small sums of money—half the soldiers have not a cent.”

Drum-Taps is the large group of poems that comes out of these years: a good many of them drawn directly from the Virginia fields of the harvest of the lost and almost lost, “Vigil Strange I Kept on the Field One Night,” “The Wound-Dresser,” “A Sight in Camp in the Daybreak Gray and Dim,” and the wonderful postcard-size poems such as “Cavalry Crossing a Ford” and “By Bivouac’s Fitful Flame.” All the war poems are beautifully observed, accurately rendered, passionately felt. Each of them, in its own way, keeps vigil, marches in the ranks on a road unknown, on a “route through a heavy wood with muffled steps in the darkness.” They all see “shadows of the deepest, deepest black.” Whitman will spend these several war years working poorly paying jobs in order to support not only himself but his constant visits to the various hospitals, visits that after 1863 become central to his Washington residence. By 1864, “saturated with the virus of the hospitals”—as one of his doctors puts it—Whitman himself becomes one of the wounded, “having too deeply imbibed poison into his system.” What exactly is ailing him is not clear, but exhaustion combined with exposure cannot have helped. Nor can the emotional toll be discounted. He is forty-five now, with twenty-eight more years to live the compromised life of a veteran.

As a coda to Drum-Taps, Whitman’s great Civil War elegy for Lincoln and the nation closes the book on his personal connection to the tragedy and its consequences but not on his afterlife in Washington. He’ll hang on in the recovering city until 1873, occupying different posts for the government, moving from one job to another, usually because of Leaves of Grass. Health juxtaposed in a slant rhyme with death has been a subtext in Whitman early on in his writing. Death and thought of death have been, like the broken soldiers, his long companions. The health of death has been that part of him that likely pulled him into his sense of mission in the hospitals. Yet the same year he writes “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry,” his visionary masterpiece of life as afterlife, he writes as well his poem of cosmic vision entitled “This Compost,” in which he imagines the whole planet as a compost heap of dead animal, vegetable, mineral, and, ultimately, human flesh. “I will not touch my flesh to the earth,” he says as if in fear of contagion. “O how can it be that the ground itself does not sicken?” He then spends quite a few of the next lines listing the “blood of herbs, roots, orchards, grains” and the “foul meat” just under the surface as his evidence. The graphic in Whitman is often underrated, and here, in this palpably corporeal poem, there’s a certain fascination with the vile vulnerability yet putrid virility of the earth. Now the poem turns, as if Whitman’s divided mind needs to redress its balance, its equilibrium: so in its second half Whitman extols what he is seeing and imagining. “Behold this compost! behold it well!” And the pun on “well”—as the antithesis of sickness—seems to me no verbal accident. He takes the word “compost” and in a stroke fills out its implication of an enriching reality: without death and burial there can be no “resurrection of the wheat … no new-born life … no lilacs blooming in the dooryards.” “What chemistry!” he exclaims. And for the rest of the poem the Earth is alive with spring and summer and “the transparent green-wash of the sea.” At this point the poem becomes Whitman’s unconscious preparation for a war that has been rumored for years.

By the end of the poem Whitman’s vision, as always, is all-embracing. In the last lines he speaks forgivingly of the paradox of life in death, death in life. Indeed, he speaks lovingly. “Now I am terrified at the Earth. … It grows such sweet things out of such corruptions, / It turns harmless and stainless on its axis, with such endless successions of diseas’d corpses, / It distills such exquisite winds out of such fetor, / It renews with such unwitting looks its prodigal, annual, sumptuous crops, / It gives such divine materials to men, and accepts such leavings from them at last.” It cannot be too difficult to pick out in this panorama the small particular faces of those young men Whitman watched die even as he ministered to their health.