On a beautiful afternoon in February, in the west end of Miami’s Little Haiti, Max Rameau and I were having trouble finding the next house on his list, though we did notice one that had potential: small, stucco, sort of a Spanish colonial, beat-up but solid on the outside. From the street we could see over the low front patio, straight through the front windows to the kitchen in the back, and even the yard beyond. Clearly it was empty. “Plus, it’s got a lockbox,” I said.

“But the evens are on this side,” Rameau said.

We looked up and down the street.

“They’ve all got lockboxes,” I said.

He yanked the handbrake. “This is how it happens. We go to look for a place, and we find three.”

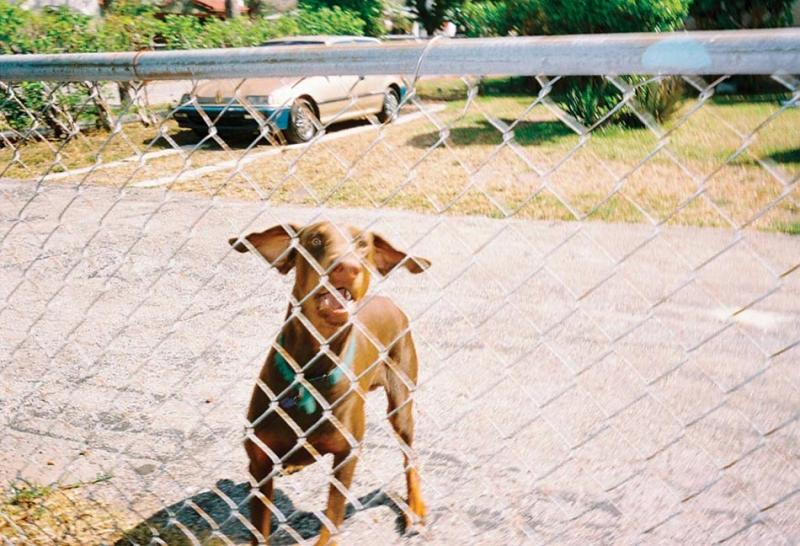

We got out and walked over to an aqua-green cottage set behind a tall, white-rail fence, with a florid, wrought-iron screen door leaning off its hinges. The block was gritty but festive, lush with palms and oaks crowding Easter-colored bungalows just like this one. About a hundred yards away, I-95 soared behind a soundwall lined with more palms. By the time Max opened the gate, the neighbor’s Doberman had spotted us. It rushed up to its chain link fence, snapped and glared and made a vicious racket. I turned and saw more dogs roaming around up the street—collared, but big and loose.

Rameau ducked around the side of the house to check the circuit breaker, found it, and fiddled with the wires. The electrical connection seemed intact. He peeked through the windows. The place looked clean enough inside, but he couldn’t find a way in to tell for sure. “Basically, I just need to get someone who’s better at breaking and entering than I am,” he said. “We have a couple of very thin people good for going through windows and stuff like that.” Rameau is slightly pudgy, medium height, with a soft boyish face, the eyes of a crooner. He’s braver than he looks. I followed him to the house’s other side, brushing against the chain-link and the slavering Doberman. Max seemed nonplussed. He found an auction sign tucked between the ferns and stoop, and dialed the number. The property had been sold just that Sunday. No worries, since there were two more foreclosures across the street, the Spanish-stucco included.

This is Rameau seizing the moment: hunting down houses left idle by the banks, or by the city, so that he can take them over. Rameau contends that everyone, no matter what, deserves a home, and he considers the surplus of empty, deteriorating foreclosures a gross waste of a precious resource. His solution is to usurp foreclosures on behalf of the homeless, to move families in crisis into houses long abandoned in a dead market, in struggling neighborhoods, and call as much attention to the act as possible—what he calls “liberating” a home—so that he can trigger a broader, philosophical discussion of how property works in America. The misdemeanor of trespassing on a bank’s property hasn’t dissuaded him so far; trespassing is the point. By doing so, he is drawing critical attention to the problem of homelessness in Miami, where the waiting list for public housing stands at seventy thousand. And while he doesn’t consider himself a homeless advocate per se (“Our issue is land-control,” he told me. “Specifically, the black community’s right to control land in the black community”), all of his recognition has come from helping the homeless—from an invasion of an empty lot in Liberty City to build a shantytown, to this most recent guerilla tactic of putting abandoned structures to a more humane use.

In this way, Rameau and his advocacy group, Take Back the Land, are moving the conversation about foreclosures toward a conversation about the homeless, and, by extension, what purpose a house serves. “For me, personally,” Rameau says, “it’s about provoking a contentious debate.” And if breaking into a bank’s neglected inventory is the way to get that conversation started, then so be it.

Crossing over to the Spanish colonial, we took a closer look, and just by what he could see through the windows Rameau knew it was unfit to squat in. The patio was missing a roof. There were holes in the floor. The whole thing was a hazard. This house would remain the bank’s problem.

We walked back to his car, settled in among the empty water bottles, a toddler’s car seat, maps, mail stuffed in the door pockets, the flotsam of a hectic life. Max started the car, shoved the folded page of addresses between the seat and handbrake, and we were off to the next house on the list.

Miami is a Technicolor city, especially in neighborhoods like Liberty City and Little Haiti, where the architecture unfolds like a graphic novel of black culture and history, painted in murals on storefronts and awnings and under overpasses. Buildings of almost every color are splashed with visages of Martin Luther King, Malcolm X, and now Barack Obama. You recognize a barbershop because a barbershop scene is painted on the storefront. Chitterlings, oxtail, wigs—everything inside is advertised without, and through a language painted in fits of color, in every breed of typeface, the city advertises a tough, bright psyche.

Rameau moved to Little Haiti in 1993, after a stint at Florida International University (where, out of a strange fidelity to the disadvantaged, he dropped out just a couple of credits shy of a degree, a decision he now regrets). He shows great affection for this neighborhood, in no small part because it keeps him grounded. Max was born in Haiti, to wealthy parents—his father, who died in 1990, was an OB/GYN; his mother is a nurse—but moved to the United States when he was just three months old, when his father took a residency with Doctor’s Hospital in Washington DC. He grew up in Landover, Maryland, but spent summers in Haiti with his grandparents, where the disparity between his family’s wealth and the country’s poor made him especially self-conscious, and got him thinking about the larger picture. “If you’re in a particular position,” he said as we were driving, “what are you doing to make things better or ride things along? Given the fact that such an overwhelming number of people in that country are poor, and our family is not, what’s the relationship between our family the rest?”

Rameau lived in Little Haiti during a wave of gentrification that produced enclaves like Buena Vista and Morningside, a boom phase that led to the displacement of a considerable number of Haitian families. “Code Enforcement would go around giving tickets to people who didn’t paint their houses frequently enough,” he says. “They’d lien people’s houses because they had chickens in the yard. These fines would balloon up to, say, two thousand dollars, and the families that had bought the place—two or three families who went in on it together—couldn’t pay, so the city takes it over and kicks them out. And then some white couple comes in and buys the place.” Rameau, too, was forced out of his apartment as part of the wave, though he got lucky, buying a home in neighboring Allapatah for less than the cost of rent—the old-fashioned way of doing it.

In response to this and other land-related issues in the black community, Rameau founded Take Back the Land, which launched its first experiment in the fall of 2006. Five years earlier, Miami-Dade County had razed a sixty-two-unit, low-income apartment complex on the corner of NW 62nd Street and 17th Avenue, in Liberty City, but never rebuilt—leaving hundreds homeless and the corner blighted. One late-October afternoon, Rameau and other volunteers raided the empty lot, building a shantytown out of pallets and plywood as the police surrounded them. Eventually the police backed down, and Umoja Village, as it was called, began to draw national attention. It was a radical move that provoked the umbrage of the city’s officials and even its ministers. The idea of an American shantytown, especially one rising up on land usurped during the city’s development triggered surprising divisions. Umoja Village lasted six months before burning to the ground: officially, a cooking fire in one of the huts spread out of control, though Max isn’t altogether convinced it was an accident. In Miami, where housing has become such a surreal, dirty battleground, his suspicions don’t seem like much of a stretch.

But despite its brevity, Max considers Umoja Village a success. Not only did it provide food and shelter, but it allowed, through a kind of utopian order, an autonomy for its residents that was otherwise well out of reach. “People who lived there made decisions about the rules of the place,” he said. “For many people, for the first time, they had some level of control over their lives. They were actually participating in a democratic process in a way that had some meaning. That was the real thing that happened there, people were given some real level of dignity.”

Seizing a neglected foreclosure involves two critical steps.

First, volunteers pore through court records and online sources to find out exactly who owns a property. “If it’s owned by some old lady who lives a few miles away, or some schmuck in Ohio,” Rameau said, “we don’t take it over.” Instead, the group capitalizes on a bank’s log-jammed inventory, or whatever the city has sitting idle. (The house Take Back the Land has controlled the longest—just over a year—isn’t even a foreclosure, but a public-housing unit the city has, essentially, ignored.)

Second, they drive: “Every street and every avenue. We write down the addresses of places that have potential. We go down, we look at it, we take notes.” Scouting allows Max to see, up close, what the data can’t tell—if the roof leaks, if the plumbing even works, if rats have infested a place, if the electrical wiring has been ripped out—whether a place is, by the rough standards of such circumstances, habitable.

On the day we drove around, scouting was mixed: most houses were too crippled for Max’s purposes, unfit even to squat safely. We found plywood over windows and plywood where a front door should have been. One property, a government-owned duplex, was sealed tight with aluminum shutters, shutting out light and air: rats in there for sure, Max guessed. Gutted air conditioners, stolen air conditioners. Houses where the floor was missing, where lizards reigned. Houses that looked brand new but so small they were more like stucco huts.

On NW 43rd Street, just inside the neighborhood of Allapatah, the yellow ranch we were looking for had a FOR SALE sign out front, which wasn’t necessarily a deterrent to Rameau. We walked around back, where we found the sliding glass door wide open. Max stepped inside, sang a soft “Hello?” We were alone.

Whoever lost the house had been remodeling it. They’d put in granite countertops, and the cabinets looked new. But the walls were pocked with holes—someone seeking copper. The circuit breaker was missing; the water heater, too. Every appliance had been taken out. The place was eviscerated. The only personal effect left was a poster of Lil’ Kim taped next to the entrance to the master bathroom. “Thing is, you never know who took it,” Max said. “Was it the agent? The homeowner? I know this lawyer, he has clients who get foreclosed on. He defends them in court, but once they lose the house, he sends his guys to take the appliances. I mean, he represents them in good faith, but once the house is empty he goes in and cleans it out.”

Rameau turned on the faucet, and the pipes gurgled. “We’d consider moving someone in,” he said, though it would require putting up a solar panel. “That and we’d have to figure out if we can get the water running.” Heat wafted down from a hole in the ceiling. “We’d cover up these holes,” he said, pointing. “The solar panel wouldn’t be enough to run a fridge or central air, which could be a huge problem in the summer. But there are people who live here without it anyway. We just have to see how the trees shade out.” The solar panel would simply have to do. He’d call together some volunteers to complete what repairs they could; the family would do their part by cleaning.

On NW 49th Street, we crossed the lawn into a mustard-colored cottage with faux Doric columns flanking a tiny front porch. The house was relatively new but sagged in the middle. The front door was missing. We could see blankets piled into a makeshift bed in one room, where another sheet covered the window. An announcement was taped to a window out front, declaring the place abandoned, which meant that the county would soon put a lien on it. In the yard lay a Betty Boop doll clutching a stuffed heart printed with the words BE MINE.

On NW 75th Street, Max pulled up to a white-stucco two-bedroom with a narrow stoop. He’d liberated the house a year before, though the family was evicted after just four months. The house had been sitting empty since. On both sides of the front door, glass block rose to about the level of the doorknob and was topped by cheap aluminum windows encased in concrete—a repair job, and a sloppy one. One window was lower than the other, the lower one shaded by an awning, the higher one encased in a wrought-iron grill. Along the side of the house, more iron grills, but with plywood covering where glass should have been. Beer bottles lay scattered in the grass.

When the family lived here, Max said, all the windows were intact; the front ones were jalousies, shattered by vandals after the family was evicted. Vandals had preceded them, too. Upon taking over the house, Take Back the Land covered holes in the walls where the copper had been ripped out. To make up for the damaged wiring, Serve the People, a sister organization, donated a small solar panel, which was planted on the roof, providing just enough power. Max pointed to the tiny stoop, where white paint dripped over the tile. The week before the move-in, he dropped by to check on the place, and discovered that the couple moving in had already come and painted it. “They took pride in the fact that they were here,” he said. “I’m not going to argue with you, they didn’t do a great job, but I think it says something that they took the initiative. And at that point it became their house.”

Walking around the lot, Max sounded increasingly upset. “This is really infuriating,” he said, “because that family could have been staying here. If you charged them $200 a month, the bank’s going to break even. Right now they’re losing a shitload of money. It’s just sitting here empty. There’s no one living in it, it’s not doing anyone any good. It’s not doing the bank any good. It’s obviously been broken into a number of times.” He stared at it. “What’s the point?”

On Friday morning, Rameau was visited by a family that had been evicted from a two-bedroom house on NW 137th St. He already knew one of the family members—Mary Trody, who volunteered at the Miami Workers Center. Trody’s mother, Carolyn Conley, owned the house. In November 2008, Trody and her husband, Antlee Accius, moved in with Conley, saying that their landlord had gone into foreclosure. Both Accius and Trody worked part-time, night shifts: Accius delivered copies of the Miami Herald; Trody stocked groceries at a Winn Dixie. When they moved in with Conley, they brought a big family with them: their son, Sylvester, and daughters Annie and Mia. Mia herself was a mother of four, and brought along her boyfriend, Brandon. As of Friday afternoon, Conley was staying with her fiancé in a house without electricity and water; Trody’s family had packed everything they could into a bread truck and were now living in it.

I found Max in front of the house—a pale-gray, post-war ranch with wide vinyl siding. He paced the yard amid the furniture the trash-out crew had set outside: a La-Z-Boy and ottoman, a couple of metal foldout chairs, a dresser, a microwave and a couple of twin mattresses. Black garbage bags, stuffed with smaller possessions. In a day or so, according to county eviction codes, the trash-out crew would return to haul whatever wasn’t salvaged, or stolen, off to the dump. The yard was dry, the grass dead in spots. None of the family was there.

Max made one call after another, planning a very public showdown for Monday morning, when he would move the Trodys back in with reporters and camera crews at the ready. But something didn’t feel quite right. I walked around the house, then looked back and realized the pattern of the scattered trash—bottles, cups, paper, pieces of the house—didn’t fall into a radius that suggested a trash-out crew’s work. The garbage was strewn in such a way that its reach and pattern suggested an abandon over time, a slow blight. I looked through the windows and saw a raw plywood floor; in every room, the carpet had been ripped out. I had seen hundreds of places like this. Each triggered its own combination of revulsion and pity and anger, and each required its own discipline to decipher and explain. What’s left behind, in the way it falls or is tossed, is never just junk but a stroke of sorts, a mark, the chalk line around a body, the tags near the casings.

Given one of the promises of Take Back the Land’s mission—that, rather than let a foreclosure sit like an open target, a squatting family can protect its value, thus protecting the value of the neighborhood—I wondered if moving a family back into a home they’d let deteriorate made things a little more complicated. Conley had lived here for over twenty years, and the family claimed an emotional attachment to this place, but was it the best scene around which to stage a spectacle? “I was looking in the windows,” Max admitted. “And I was thinking to myself, ‘Let’s say we found this place. Would I move someone in here?’”

One of the neighbors had been watching and walked over. “They was here till last night,” he said. “There was an older lady staying here. I don’t know where she went.”

“She’s now staying in an empty house with no electricity,” Max said, not emphatically, but with a dose of gravitas. He explained what we were up to, what Take Back the Land does. He mentioned the truck and the children.

“Were they good neighbors?” I asked.

Max interjected. “Whether they were good neighbors or not, you have twelve people with nowhere to stay. What should be done?”

The question was rhetorical.

“These families,” he continued, “some of whom have been struggling for years, and making bad decisions for years, a combination of bad decisions and being poorly educated and being taken advantage of, I don’t think it would be reasonable for us to expect them to somehow see clearly and rise above all that suddenly, miraculously, just because we moved them into a house. That’s not to say we don’t get frustrated with people, because we do. But I don’t want to be judgmental about it.”

A landscaping truck pulled up in front of the foreclosure across the street. The crew got out, cranked up their blades and blowers, and went to work.

Max surveyed the yard, the Trody house, taking it all in, weighing it. “So I’m leaning towards doing this,” he said. He made a few more calls to put the word out. He expected about twenty-five people to show up on Monday and for the group to thin out once the police arrived. He and the core members were prepared to chain themselves to the home in defense of the Trodys’ right to stay. I thought he was speaking figuratively, but then he led me to his car, where he opened the trunk, dug around among the clothes and books and pulled out a gleaming quarter-inch chain fit to pull a car.

If things went well, it would all make the news at six.

On Monday, everything fell into place. A couple dozen people showed up at the Trodys’ house with banners and painted bed sheets to drape across the facade—signs for LIFFT (Low Income Families Fighting Together) and the Miami Workers Center. Media presence was heavy: nearly every local station had sent a camera crew, including the Spanish-language stations. The Herald had sent a reporter. Freelance writers and photographers were there, with venues like the New York Times and Mother Jones in mind. Even director Michael Moore had sent a crew, which had arrived over the weekend to collect footage for his film Capitalism: A Love Story, a new documentary about the economic crisis.

Trody held still while a member of Moore’s crew fiddled with her microphone battery, and tried to answer questions, but kept interrupting herself whenever she saw someone she recognized, darting off to greet old friends, hugs all around. The mood was electric, festive, voices high.

Three calls were made to Chris Richards, the agent listed on GMAC’s for sale sign, in hope of provoking him to come down to the property, or to call the police, or both.

By mid-morning, at Max’s instructions, the crowd formed a circle. Hashim Benford of the Miami Workers Center led a few chants—Up with People! Yeah, Yeah! Down with the Banks! Boom, Boom! Neighbors strolled past and paused, but kept their distance. After the groups were introduced, Trody was ushered into the circle and asked to say a few words. She was obviously moved by the show of support, but anxious, too, about what the police would do when they eventually showed up. Her nerves were tweaked. The speech unraveled in a kind of awkward, angry improvisation.

Then Conley moved to the center of the circle. “This is my home,” she said. “These banks and these people that sit behind the desk and say they gonna do this and do that, they need to come out here. Come live on the streets for a week or two and find out what it’s like for the families! ‘We’re gonna do this, we’re gonna do that.’ No, you’re not doing nothing to help the families!” She started again: “I believe in God almighty”—and here was something that hooked the crowd, and it applauded, crisp and loud. Conley seemed to feed off the enthusiasm. “These people in the churches, listen to me. I know there’s a God. Y’all watch TV. You watch everything underneath the sun. You talk, but you don’t get out here—and fight! I’m here to fight! Come fight with me! Make these banks come and talk to you and find out what kind of income you can give them until you settle. Don’t throw the people out. It’s got to stop! I’m sixty-six years old, and if I can stand here and fight, y’all can stand up and fight!” That did the job: the circle cheered.

Then, as a kind of benediction, Rameau walked forward, and repeated the principles being defended. “We believe it is immoral to have vacant homes boarded up while you have human beings out on the street,” he said. “And right now we have to make a decision about which is more important for this community to support: corporations to make big profits or human beings to have housing. We think it’s human beings to have housing. So on behalf of this family and this community, we liberate this home.” The crowd applauded, and slowly people began picking up the furniture and moving it inside to chants of community power.

Chris Velozik, owner of Velozik Enterprises, led the trash-out crew that evicted the Trodys on Friday morning. He had intended to return to Conley’s house on Saturday to follow up but never had a chance until now. Trim and tan, Velozik wore a company T-shirt (SPECIALIZING IN FORECLOSURE SERVICES), underneath which I could see the bulge of a pistol. And if he was surprised when he pulled up to find a crowd gathered in the Trodys’ front yard, the furniture moved back inside, he didn’t show it. He walked to the door, a clipboard tucked in his arm, and looked around. Then he told everyone it was time to go.

Max insisted he reconsider, and the two faced off—politely but firmly—there in the doorway.

“Let me tell you something,” Velozik said. “The bank offered them—the realtor offered them—two thousand dollars to give them money to rent a place. They said no.”

“Right now they are living in a truck,” Max said. “This place is empty. There’s an empty house over there, which is in much better condition. That house is going to sell way before this one.”

“That’s not my problem, sir. If the bank permits you to go inside—”

“The bank isn’t making any money by this unit staying empty and this family being homeless,” Max said. “So call them and let them know the humanitarian thing to do.” Of course, Velozik had about as much a chance of reaching someone at GMAC who could overturn the foreclosure as Max did, but Velozik wasn’t in the mood to explain.

“I work for the bank,” he said. “They tell me to do the job. If I don’t do it, they’ll find somebody else to do it.”

Trody’s daughter Mia shouted at him. “It’s not right she’s been in this house for twenty-two years and y’all going to put her out. It’s not right! And you come in here saying that we’re trespassing? We should be telling you that you trespassing, because this is our house! You don’t know what’s going on in this house. She brung us up in this house!”

“We was raised in this house,” Trody shouted, and she launched into a shrieking excoriation of Velozik and all he represented. This was the closest anyone here would get to cornering someone who had anything to do with an otherwise anonymous and unrepentant power—The Bank, the invisible and apparently indifferent institution that steered their lives. It now had a face, and while Velozik couldn’t authorize anything, he would suffice as an outlet for their rage.

“I got a question,” one man said. “Where is the money the federal government put in the banks? Where is that money?”

“Why don’t you ask Obama?” Velozik said, getting fed up.

The crowd howled at him.

The man insisted “I’m asking you because you represent the bank! Where is the money Obama or whatever put in the hand of the bank?”

Velozik kept quiet.

“You cannot answer?”

“Ask the bank,” he said.

They howled again.

“You is the bank,” Mia said. “That’s what you said. So why you here representing the bank if you can’t even answer the question!”

“The bank wants the property back.”

“Want it back?” Mia shouted, “for what? To sit on the block! They gonna come here, and they gonna tear the frame out the windows, and it’s going to be a piece of dust before tomorrow. It’s sitting here empty! Do you have a heart? Think about it, do you have a heart? Kids got nowhere to go, and you sitting here telling us the bank wants this property back! To sit here empty like this house, that house two houses down the street, and the one over here!”

Conley struggled forward. “Do you know who God is? Do you go to church? Answer me!”

“Sure.”

“You believe in God, you do? Does the bank believe in God?”

“Who financed the house for you?” Velozik asked her.

“Option One,” she said.

“Have you spoken to them? What have they told you?”

“I tried to do a reverse mortgage,” Conley said.

Mia shouted, “She was ripped off! It was a predatory lender! She got ripped off!”

“I had people come in here and say they gonna do a reverse mortgage,” Conley said. “I was all for that. I signed papers. They tell me everything is fine. I can live here the rest of my life, just pay the taxes. The next thing I get is these foreclosure notices. What kind of deal is that?”

“They didn’t make arrangements?”

“They didn’t make nothing with her,” Mia said. “This is what I’m telling you. This is why when the foreclosure notices came, everybody was sitting there in shock.”

“I know I can’t read and write good,” Conley said, subdued now, almost reflective. “I know my education. And I’m finding out now that people are out here taking advantage of people.”

In fact, court records show that Conley borrowed $119,000 against the house in 2005, and that a lis pendens (the motion that begins a foreclosure process) was issued in March 2007. Rumors circulated quietly among the crowd that an ex-boyfriend had blown through a lot of that money, and that the siding repairs had sucked up the rest. Whatever happened to the money, there was hardly any evidence it had done any good. But what was obvious to a lot of people in the yard that day, supporters and detractors alike, was that the house could never have reasonably been worth what was borrowed against it—no matter the fly-by-night appraiser’s opinion, or more likely, because of it.

“I don’t have a choice,” Velozik said. He pulled out his cell phone and called the police.

Max was giving the Trodys a pep talk when six patrol cars lurched up the block. “There are two kinds of arrests,” he said. “There’s the kind that happens when you do something objectively wrong, like hurt somebody or steal something. And there’s the kind of arrest that ultimately benefits society. I don’t like it when people glorify the first kind of arrest, but this is a good kind.”

The cops approached, talked to Velozik, then tried to coax Trody away from the crowd, asking to speak with her. Rameau stepped in. “We don’t want to have her isolated,” he said.

“Well, you’re not in charge here,” the officer replied.

Max turned to Trody. “You don’t have to say anything.”

“Do I have to repeat myself?” the officer asked. “You’re not in charge. We’ll speak with her, we’ll explain the law, and you’re not going to decide whether or not she comes back with me, you understand?”

Max advised Trody that she wasn’t obligated to say anything, that no harm would come to her if she simply kept quiet. The crowd amped up the chants: Housing is a Human Right! We Won’t Go without a Fight! One of Take Back the Land’s volunteers designated as police liaison, a woman named Poncho, approached the officer. They’d arrived at around eleven that morning, she told him, and everything done since was on camera. The doors weren’t locked when they arrived, they didn’t know how or why, and before entering the house, they had called the realtor.

“Did you see any legal notices on the door?” the officer asked her.

“No, sir, not on the door. And I don’t want there to be any misconceptions. We’re not trying to hide or be sneaky.”

“Obviously not,” he said.

After a lot of deliberation at the far end of the block, the police advised Velozik to file a report. It made little sense to arrest a sixty-six-year-old grandmother and her family in front of the local news. But their retreat seemed too easy; Rameau suspected they’d be back after the eleven o’clock live report was filed. As soon as the police pulled away, he began calling commissioners, the police chief, the mayor’s office to try and win some promise of protection for Trody and her family, that they not be thrown out overnight.

Afternoon dragged into early evening, until most of the crowd had thinned out. Moore’s crew stuck around, along with a couple of news trucks. Rameau kept waiting. Unmarked cruisers rolled past on the hour. Mia’s children finally arrived. By the time the sun was low, a break: a police officer Max knew called offering to ask Miami’s police chief John Timoney that the family not be kicked out overnight. Max considered it an important gesture. “It doesn’t necessarily mean they’re going to let you stay here long,” he told Trody. “But that’s the first step.”

In a few hours, Trody would begin the night shift at Winn Dixie. She looked spent. “I really need you to take a nap,” Max told her. She began to cry there in the recliner, exhausted.

Around nine that night, Take Back the Land’s banner came down off the bread truck. A wind picked up, whipping the banner as it came loose. The Channel 10 van’s lamps clicked off, its generator falling quiet. As I was leaving, I saw Trody, too nervous to sleep in the house, creep back into the truck, just in case.

For the rest of winter, through spring and into summer, the police kept their distance. Miami police chief John Timoney hinted at the department’s unofficial position, when he told ABC News in April, “What social good would be served by arresting the mother, and then separating her from the children?”

With the summer came an upswing. The Dow regained four month’s worth of losses, cresting just above 9,000 points. New-home sales increased in several cities, after prices had flattened out in the spring. JPMorgan Chase and Goldman Sachs stunned Wall Street with record profits (which also raised a flag of caution for economic skeptics). Bank of America and Citigroup followed suit, though with profits from a one-time gain from selling assets that winter.

Foreclosures, meanwhile, were holding steady, with a shadow inventory of homes that weren’t even on the market yet. Mortgage relief had proved hard to come by, nowhere near the level the Obama administration had promised back in February. By summer, the latest dirty economic secret exposed was that the mortgage holding companies actually made substantial fees from letting foreclosures drag out—profiting, in other words, from a homeowner’s inability to modify a troubled mortgage. And the homeless were growing in need and number. In the first half of 2009 Miami had the fourth-highest number of properties, nationwide—homes, condos, businesses—that received a foreclosure notice, and odds were that a considerable number of the names on those notices would be appearing on a growing waiting list for public housing in Miami.

In April, the New York Times ran a front-page story about Take Back the Land, based on the showdown at the Trodys’ house. ABC visited next, the BBC followed. By the time I returned to Miami in late June, NBC was knocking on the door. Mary Trody and Carolyn Conley were both beginning to burn out. They hadn’t anticipated such attention, Rameau told me, and were suffering from what he called “media fatigue.” He’d expected as much: during the first spate of press during Christmas, Take Back the Land’s go-to case was a doctoral student, a single mother of four who’d been abandoned by her husband. She was an immigrant, articulate, and the house looked spotless in every shot. She was, in many ways, an ideal ambassador of the mission. Eventually, the pressure of reporters became maddening. It is a lot to ask of people piecing their lives back together to expose themselves to the camera’s bright ogling, week after week. It saps an energy otherwise better spent. Within a few months, she refused to do any more interviews. Now Trody was close to requesting the same, but the crews were still lining up—Swedish television, French television, Australian, Japanese, and German. “The ethical dilemma is that I need to do the media part,” Max said. “I actually want to turn them out to the media all the time, and do well, and perform well. And yet I have an obligation to protect them, even though protecting them doesn’t move history.”

Max, too, was close to burning out. He had just returned from a hectic round of cross-country speaking engagements, as well as a tour of Gaza, and was, during his weeks at home, struggling to make ends meet. We met up in Coconut Grove, where he’d gotten a gig installing a computer network for a small law firm. Between his talking points and takeovers, things were starting to slip. “I was driving around the other day,” he told me. “I’d just come back from giving a speech the day before. And I knew I was going to speak about it again, and I was looking at the house, and in my mind’s eye looking at myself look at the house, so I could figure out how I was going to talk about it, and I just totally freaked out.”

But there was progress. Early in the summer he was invited to an informal roundtable by Miami-Dade commissioner Katy Sorenson, who paired Max with Judge Jennifer Bailey and Arden Shank, of Neighborhood Housing Services, to try and brainstorm a strategy and, as Sorenson put it, “figure out if there’s a way to go legal with all this stuff, figure out how to take an outlaw activity and make it a sanctioned activity that involves institutions and would benefit the whole community.” No statutes were expected, but at least they could draft an informal policy that would allow banks and housing nonprofits to work together. Rameau was happy to trade ideas, he told me, but not at all interested in playing a subtler role. Politics isn’t his arena. He prefers the action on the ground.

To that end, he was busy planning Take Back the Land’s growth on two fronts: “Locally, we’re going to start working on defenses instead of liberations,” he said, which was no less risky a tactic—technically, it’s still trespassing—but stood to draw greater popular support, since it worked to keep families in their own homes, approaching homelessness at the source. But he wasn’t abandoning liberations altogether; rather, he wanted to see Take Back the Land’s model replicated in other cities. “The big question is, can we do enough liberations to force the debate in something other than an abstract way, and say, ‘Look: right now, numerous organizations across the United States have control of over fifty thousand houses—what are we going to do now?’ Right now, we’re just not in a position to negotiate.”

Fifty thousand houses sounded like an extremely ambitious, if not fantastical, number. But ACORN and New York’s Picture the Homeless had already taken a page from Rameau’s book, breaking into foreclosures and squatting on private empty lots, with arrests to show for it.

Some of Rameau’s critics consider his refusal to enter the political fray—to affect policy through diplomacy and carry the mission off the front yard and into city hall—as immature and self-serving, an activism more committed to confrontation than methodical change. But this is Miami, a city with a notorious political history, and a notoriously dysfunctional housing policy. Max knows how to pick his fights. “Quite frankly, these organizations are very slow right now in doing something,” he said of the city’s housing programs. “There’s a lot of potential for stuff to happen, but in a year, if people don’t start moving right now, all the potential for significant change will be gone.”

As one county official told me, when I asked him about Rameau’s insistence on keeping the fight on the street, “We don’t have many people who are good at that here, and it does serve a purpose. He was in the New York Times and for what—nine houses? It’s brought a lot of attention here in positive ways. But what’s happened here because of it? Nothing. Our political and administrative systems are so broken that there hasn’t been much good response to what Max is doing. If he ended up being a politician and being a county commissioner, he wouldn’t get anything done.”

Commissioner Sorenson, who arranged the roundtable, hopes to prove otherwise. In July, she met with the head of the Florida Banker’s Association, Alex Sanchez, to try and move a discussion forward. The challenge, she said, is that “banks are just not used to thinking creatively; they’re used to thinking like banks.”

The county already has some success in getting the banks to improvise. When tenants called to complain after the water had been shut off in their building—the foreclosed landlord had abandoned it long before—Jeremy Glazer, a member of Sorenson’s staff, working with the County’s Water and Sewer Department, contacted the bank’s lawyer, who quickly understood the logic of keeping rent-paying tenants in place, and took the matter into his own hands, using his own credit card to turn the water back on and restore as much normalcy to the building as possible.

It wasn’t exactly a paradigm shift for the bank. It was, after all, an economic decision, and the lawyer’s at that. And despite the economic advantages of having foreclosures occupied and tended—with tenants, homeowners, and homeless alike—the banks face a potentially very thorny problem in doing so. “Banks are not in the property management business,” Glazer said. They’re scared of doing anything like this.” The solution lay in distributing that responsibility to local nonprofits, such as Miami’s Neighborhood Housing Services, which would coordinate housing using the bank’s backed-up inventory, even negotiating paths toward ownership. The trouble was breaking through the Byzantine structure of the banks themselves. It took until the summer of 2009 for most to begin hiring and training enough agents to handle remodifications; there was no telling how deep overstock was and whether the difficulty in filling those foreclosures was a matter of the overwhelming work at hand or a stubborn faith in free-market forces. Never mind that now some banks were walking away from properties altogether—just like the people they had complained were the problem.

Our last drive together, we left Rameau’s house and drove uptown along 12th Avenue, past the “segregation wall”—a foot-high berm, remnant of what was once a six-foot wall that demarcated Miami’s black part of town, past which the black community wasn’t allowed to cross after dark (he was helping to petition to make it a historical marker)—and up to 75th, to the house he’d shown me last winter, where the jalousie windows had been shattered and so poorly substituted. Pieces of plumbing spilled out from the crawl space, where it had been scavenged since our last visit. The house next door was also now foreclosed, and inside we could see the black stains where squatters had tried to start a fire during a cold spell. We shot over to NE 2nd Avenue, turning south, toward downtown. Second Avenue offers an epic, sweeping perspective of the city, running straight from the ghetto toward the bay’s glamorous towers, through Little Haiti and Buena Vista, past the savvy Design District, and into the heart of downtown. History lay all along this strip.

“At what point would you consider your mission accomplished?” I asked Rameau.

“When we don’t have anyone who’s coming to us.”

That likely wouldn’t happen anytime soon, he said. “I’m not that enthusiastic about it now, mainly because we don’t have critical mass. If Miami were doing twenty move-ins a month, with ten different organizations, then I think that would happen. Critical mass would overwhelm the system.”

Perhaps, but there was also the potential of crossing over into other neighborhoods, where his liberations would have a different social impact. “If you keep this in Liberty City,” I suggested, “you’re probably not going to get the kind of contentious debate you want.” Would he rather create an even bigger stir in mostly white, middle-class subdivisions like Cutler Bay and Pinecrest?

“If we go into Culter Bay,” Rameau countered, “do we move in a white family? Because we don’t want to have to knock down two walls at the same time. If we’re going into neighborhoods now and the neighbors are supporting what we’re doing—even if there’s some trepidation—going into a white neighborhood and moving in a low-income black family just confuses the issue. We won’t know whether they are opposed to the family because of race or class, and it doesn’t help us in improving our own communities. We’d be out doing this in other communities, so there’s not really any benefit.”

But there was one thing he wanted to show me. He directed me onto Bayshore Drive, up to Morningside, an upscale neighborhood of Jazz Age mansions and one of the city’s most scenic public parks, but where, during the boom, the streets along Bayshore were redesigned to create a bit more privacy. “When I lived here,” Max said, pointing to the landscaped berms, “these didn’t exist. You can’t go through there now because there’s a big plant there. That didn’t used to be there. And there was no guard gate.”

As we approached the gate, I slowed into a U-turn.

“Keep going!” he said.

“We can go through?”

“Yeah! See the reaction you had?”

I rolled the window down as I slipped through the gate, but the guard ignored me.

“You don’t have to put the window down, you don’t have to explain anything,” Max said, as incredulous as if he’d just discovered this secret. “It’s a public road. But when they put that guard gate there, all the Haitian families that used to come here make U-turns and leave, which is exactly what they wanted.”

The neighborhood was thick with palms and other trees of an almost prehistoric grandeur. I could see the bay glimmering between the shrubbery. Then Max asked me to turn into what looked like an empty overgrown lot. I rolled over the carpet of fronds and small branches. Then I saw it: a red sprawling ranch, mid-century, set back at the end of a curving brick driveway buried under the tarp of leaves, nearly swallowed up by the trees and vines that surrounded it. It bespoke lost aristocracy and had an archeological vibe, shrouded as it was.

It began to rain, at first a drizzle, then a downpour loud and full. You could hear the drops were big, snapping a loud drumline on the truck’s roof. We scrambled out into the downpour and crossed the courtyard to peek through the front-door glass. The inside was empty. You could fit a family of twelve, or two families of six, or who knows how many combinations, very comfortably. You could create a utopian commune here. We picked through the overgrowth around the side, ducked past the brick grill, and made our way onto a wide back lawn that stretched toward the water, with a clear panorama of the bay and Miami Beach beyond. Suddenly the storm was a broad show; you felt the God-drenched zen found in seaboard vistas, a humility in the face of nature. I could imagine shaking off many troubles staring out at this sea, in rains like this one.

“So talk about taking this thing to the next step,” Max said, grinning. “This would be the place to do it.”

I had to admit it was a hell of an idea.

Research assistance provided by The Investigative Fund of The Nation Institute.