- “The environment to which a society actually adjusts itself is not the material environment that natural science can reconstruct and observe as an external object, but the society’s collective representation of that environment—that is, part of its culture.”

- V. Gordon Childe, Social Worlds of Knowledge, 1949

- A Quechua man wears the Incan flag as he ascends El Señor de Qoyllur Rit’i, the retreating glacier the Quechua believe is sacred.

One June afternoon, 15,600 feet up in the Eastern Andes of Peru, a man stops a matronly Quechua woman as she descends a steep, windswept moraine. He grabs a baggie from her hand and empties out the ice chunk held within, which she had just collected from the nearby glacier they both revere as sacred. Ice shards, like falling diamonds, bounce off a pile of other chunks behind him.

“But why can’t we take ice?” the woman asks.

“Nobody goes down with ice,” the man says and sends her on her way. Far below where they stand is a vast scrubland, encircled by an inverted moat of swollen, baking mountains. Milky glacial streams crisscross the land like veins. The red roof of a church stands out among an ephemeral tent city that shelters some forty thousand Peruvian pilgrims. They have journeyed here under the fat moon of the winter solstice to celebrate one of the world’s highest, most remote religious festivals in honor of “El Señor de Qoyllur Rit’i,” the God of the Snow Star—who resides in the area’s alpine glaciers.

Roner Ramos, the man perched on the moraine, wears a New York Yankees cap, fuzz on his chin, and a large gold cross. His eyes scan people who pass for any sign that they’re packing ice. He’s one of the festival’s thousands of ukukus, the dancing bear men who dominate Qoyllur Rit’i. Out of all the attending devotees, the ukukus have the most significant role; they protect and communicate with the glacier god by roaming and dancing on the glaciers from midnight until dawn.

Ukuku means “bear” in the Quechua language, and ukukus represent the wily offspring of an Amazonian spectacled bear and a peasant woman. They dress in shaggy smocks, woolen ski masks and speak only in falsetto. Ramos will don his costume later, when he joins his troupe. But for the afternoon, he is acting as a sentry. Everyone who passes is searched and forced to relinquish any glacial ice that they’ve collected to bring home.

“Long ago there was an abundance of ice here,” Ramos says, his forehead wrinkling. “But nowadays, as the earth suffers from this global warming, we ukukus have proclaimed that nobody will leave with even one block of ice.” In the night, when the ukukus climb to the glaciers, he says, it’s more dangerous than before because they have to climb much higher to reach the ice. The ukukus themselves used to carve large blocks from the glaciers by sawing away with their rope whips or using picks. They then tied the blocks to their backs and carried them down to the sanctuary, or sometimes on to distant villages, where the glacial melt was conserved as holy water for the year. Quechua people believe it possesses curative properties and bestows fecundity on families and their lands, that it is the holy nectar of the apus, or mountain gods. Sick people drink it. Women wash their babies in it. But as greenhouse gases warm the planet, this glacier is disappearing and the sacred water it spawns will soon be gone with it.

A voluptuous teenage girl walks by, swinging a bag of ice and carrying a plastic Coca-Cola bottle of glacial melt water.

“Your ice please,” Roner says, stopping her with his arm and seizing the bag.

“What?”

“It’s prohibited.”

“What? Why?”

“The glacier. Here, take this bit if you want,” he says, pinching a little ice out of the bag. She hesitates. “Take it if you want. But no more,” he says.

She takes the little bit of ice in her fingers and slowly brings it to her lips and sucks on it, watching as Roner empties the rest from her baggie onto his pile.

“What’s happening here?” she asks.

“It’s melting. We don’t have ice anymore. We have to climb higher and higher at night.”

“Really?”

“Look how it is,” Roner says, pointing to the glacier, exasperated.

“It shouldn’t be like that?”

“No,” he says, “it should extend much farther down.”

- A Quechua woman looks out at the thousands of pilgrims gathered in the valley below the glacier to pray to El Señor de Qoyllur Rit’i.

This isn’t the only glacier that’s melting, of course. Almost every glacier is melting. Melting has doubled in the Alps since 2000, the Himalayas have lost a quarter of their ice, Glacier National Park in Montana will need a new name sometime in the next decade or two. But nowhere is the melt faster than in the Andes, where ninety-nine percent of the world’s tropical glaciers can be found. The rate of retreat for Quelccaya, the world’s largest tropical ice cap, located in southern Peru, has increased tenfold in the last thirty years—from twenty feet per year to over two hundred feet per year—according to glaciologist Lonnie Thompson of Ohio State University.

Here in the Andes, where the sun shines hot all year long, scientists on the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) estimate that 80 percent of the glaciers will be gone by the time today’s small children reach adolescence. That will cause all kinds of grief. Some 70 percent of Peru’s freshwater supply drains off these peaks during the five- to six-month dry season.

“When there are no more glaciers,” Patrick Ginot, a French glaciologist who works in Bolivia, told me, “you’ll have a big stream flow during the summer and no more water during the winter.” The 2007 IPCC report also projects that southern Peru will receive less rainfall with higher temperatures. To top it all off, while the water supply is drying up, the population in Peru’s capital, Lima, situated in a coastal desert, is skyrocketing. Two ice-capped mountain ranges that feed Lima, the Cordillera Raura and Huaytapallana, have lost 50 and 75 percent of their ice since 1970.

“In twenty or so years, we need to have an alternative plan for the dry season,” Robert Gallaire, another French glaciologist based in Lima, said. “We could take water from the Amazon, which would be a very large and difficult task. The alternative would be to displace all human activity into the Amazon. But I don’t believe that’s going to happen.”

But it’s not just lives that are at risk; it’s cultures—how people understand who they are. How they perceive their environment. Identity is on the line. Meaning is melting.

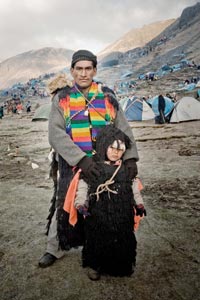

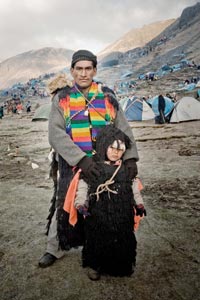

- A young ukuku and his father in the festival campground below the glaciers. The honor of being an ukuku is passed down only through family.

The Qoyllur Rit’i festival originates in the Quechua’s worship of the Pachamama, Mother Earth, and all her manifestations. The Quechua believe that apus are such manifestations—the spirits of the ice-capped mountains and rolling grasslands, where farmers graze their alpacas, where condors soar over sapphire lakes. Each apu is a distinct individual, the personification of the primeval landscape that predates all other living beings. They bestow health, fertility, and abundance on their devotees, but, of course, also have the power to take those gifts away. To keep them happy, the Quechua make regular, even daily offerings to the Pachamama. Even before taking a drink of chicha, a corn-based beer, many Quechua first pour some onto the ground.

The Qoyllur Rit’i sanctuary lies close to the region’s highest peak, Mount Ausangate, to which locals, who consider it their most powerful apu, used to sacrifice llamas—and even small children—long before the Spanish arrived in South America. When the Spanish did arrive, they understood that the easiest route to converting the natives to Catholicism was to combine the new religion with the old. Miracles occurred with suspicious frequency at sites that were already sacred. And so it happened at Qoyllur Rit’i.

In 1783, according to one version, a white child named Manuel appeared to an Indian shepherd boy named Mariano in the glacial valley below Ausangate. Soon little Mariano brought local Catholic priests up to the pasture to see his new friend, this blue-eyed child. When they arrived, a great white light suddenly emanated from the white boy and he transformed into Jesus Christ, dying in agony, suspended from the branches of a nearby tree (even though the site is far above the tree line). When the priests came to their senses, they saw that the tree had turned into a wooden crucifix and Mariano had died from a broken heart. They buried him under a boulder lying near the glacier’s edge.

According to the legend, as the local Quechua began gathering near the rock to light candles, church officials painted an image of the crucifix on the crag. A church was built around this crag and the painted image supposedly never fades. Many Qoyllur Rit’i pilgrims believe that the spirit of the boy lives in the rock and surrounding glacial landscape and that he roams the ice at night. The annual pilgrimage is simultaneously a visit to the Christian shrine and to the pagan mountain deity.

So—a charged place. Maybe supercharged. One prophecy about Mount Ausangate, as recorded by anthropologist Michael Sallnow, goes: “For the arrival of the final judgment, you, Apu Ausangate, little by little will become grey until you have turned completely black. And when you have changed into a mountain of black cinder, on that day will come the final judgment.” Throughout the Andes, peoples have long believed that when the glaciers melt, the world will end, or a mighty wind will blow everything away and a new epoch will begin.

“The disappearance of the glaciers is something that they had beliefs about,” said Ben Orlove, an environmental anthropologist at the University of California, Davis, who is studying the impacts of glacial melt in Peru and around the world. “I think, in a way, that they never expected the glaciers to go away—it was just an image of how things could never change. But now they are changing.”

To see this change, I began the trip to Qoyllur Rit’i with a late-night bus ride from Cusco to the dusty village of Mawallani, five hours to the southeast. From there, in the middle of the full-moon night, I followed the dark shadows of thousands up a five-mile-long mountain trail bordered by a purling glacial stream hundreds of feet below. The pilgrims were mostly rural Quechua folk, along with some urban Catholics from Cusco. Every year, more curious middle-class Peruvian tourists attend as well, as does the occasional crudo—a name slung at me, a white foreigner—which roughly translates as “raw.”

After hours passed hiking in a hallucinatory, high-altitude daze, we felt dawn’s light on our weary faces. Rounding a bend, I arrived at the top of the mountain pass—a goblin’s garden of rock cairns—and finally glimpsed a portion of the glaciers, the pilgrims’ frozen Mecca. The ice hung like a beard around the highest mountain’s black pointed peak.

Now, hours later, the sun arches westward in the sky and, after leaving the ukuku Ramos to his confiscation duties on the moraine, I have finally arrived at the lowest portion of the glacier he pointed out to me in the morning. Pilgrims are scattered across the twenty-thousand-year-old finger of ice as if inspecting some dying mythical beast. No one says much. Water streams out from the pocked and porous glacier’s face, like fluid seeping from a wound.

Climbing onto the glacier, I can see deep crevasses winding down to the bedrock. Streams of gray water gurgle below, littered with empty film cartons, Chiclets wrappers, and plastic bags. A little boy scoops melting snow into a plastic Coca-Cola bottle. Teenage boys and girls in tight jeans and soccer jerseys stand in groups. An old woman is huddled in an ice cave filled with burning votives. A few scattered ukukus are arriving.

- Ukukus, or bear-men, on mountain top just before sunrise. They stay up all night dancing, chewing coca leaves, drinking and smoking, while they guard their glacial god.

Four men in green berets and fluorescent yellow North Face jackets lounge on rocks to the side of the glacier. They look ready for the worst, carrying rope, walkie-talkies, and ice picks: the Peruvian High Mountain Rescue team. I’m surprised to see them. They tell me they only started to come a few years ago.

“What the ukukus do has no impact on the glacier,” says one, Wilder Lobo. “The problem is industrialization. It’s nothing more.”

We watch as a young ukuku above us takes a bottle of ice from a girl who is making her way back down the glacier. He empties the ice and lobs the plastic bottle into a crevasse. Lobo shakes his head.

“They don’t understand what they are charged with guarding anymore. He is stopping people from taking ice, but then throws the garbage on the mountain,” Lobo says.

More ukukus are climbing the moraine to begin their final night of ceremonies: they head high onto the center of the glacier, plant a cross in the ice, dance, and baptize new ukukus (which I’ve been told consists of a brutal whipping). What I have come to recognize as their anthem—an ominous five-note chant tooted on a wooden recorder—crescendos as they approach. Their march toward the glaciers is a signal to the other bear boys already on the ice. One puts his whistle to his mouth and waits, surveying the scene. Then he blows. The others start blowing their whistles and yelling, “¡Baje! ¡Deje el hielo!” Get down! Leave the ice!

But no one moves. People—many who look more like tourists than the devout—just stare, enchanted or bewildered by the shaggy bear boys with their wintry expressions, rope whips, and doll versions of themselves around their necks. Miniature brass bells woven into their smocks tinkle as they move. They look like sorcerers, their black hair shining in the afternoon light. Hundreds more approach the glaciers from all across the expansive valley, marching in single file to the bass drum beat, bearing large flags.

A man in a Mitsubishi leather jacket chortles at an ukuku telling him to get off the ice. But as the ukuku boys start to wave their whips, people finally start to leave. A teenager grasps his girlfriend’s hand and holds her up as they warily descend. Whistles blow constantly like everyone’s committing penalties.

I try to speak with some of the ukukus, but their breaths reek of alcohol and they all seem too incoherent to say anything more than “You must leave.” Even the High Mountain Rescue Team is leaving.

“The problem is we don’t have the equipment to scale the ice further,” Lobo tells me, as if trying to justify their lack of authority. I remark that they clearly have much more equipment than the ukukus. He shrugs.

“Look, most of the time, they go drunk. And some die up there.”

- Ukukus gather around what’s left of their melting glacier. Some of them believe it’s their fault that the glacier is disappearing.

I head back down the moraine on a different path from before, toward the arrhythmic pops of firecrackers, scattered horn riffs, laughter, shouts, and the smell of burning paper, wax, wood. Llamas, horses, donkeys, and squirrelly dogs roam.

Approaching the fringes of the festival chaos, on the lower scree-covered slopes that were covered by glaciers a few decades ago, the air becomes cloudy with viscous clay-colored dust and smoke. People are clustered amid strange little piles and formations of rocks, quartz, pebbles, and gravel, which are strewn with confetti, rainbow-colored ribbons, popped rubber balloons, hard-candy wrappers, empty Inca Kola bottles, pink plastic toy cars, fake dollar bills.

Three little girls are playing with fake money, one puts a $100 bill in her mouth. A couple scours through pebbles, bent halfway, picking up and examining one at a time. A young woman with braids and a stack of money in front of her holds her baby boy and zooms a rock in circles like an airplane before his wide eyes. A man walks by holding a wooden rack of ukuku dolls for sale.

I stop near a man on a granite knoll that forms the corner of a large square frame of pebbles piled six inches high, like a miniature corral. Inside the frame are a dozen long rectangular chunks of granite.

“What’s all this?” I say.

“My shop,” he says.

“What are you selling?” I say.

“This truck is a Volvo,” he answers, picking up one of the granite chunks, the size of his palm. “Worth $80,000. And this one,” he picks up another, longer, granite slab, “this one is a double-decker bus. Fits eighty passengers … semi-bed seats … Worth $150,000.” Nearby, a firecracker explodes in a ripple.

“Whatever you want, eh,” he says, the words rolling off his tongue with the breezy ease of a used-car salesman.

- Worn rubber sandals are a common sight in the high Andes of southern Peru, despite the frigid temperatures, ice, and steep terrain.

This mustached, middle-aged man, Eduardo Laura, is playing make-believe. Using the pebbles like Legos, he and thousands of others across the slope have created a fantasy world. People nearby are building elaborate dream mansions or three-story businesses with television antennae made from twigs. They buy and sell their property with dollars (you can buy one million fake dollars for the equivalent of about thirty American cents). All around, I realize, people are engaged in the fantasy business.

Laura explains to me that you must make the pilgrimage three times in succession for the god of Qoyllur Rit’i to grant you your prayers—that is, whatever you buy or express as your desired property in the pebble game. A sale nearby is made. The property is blessed with a forty-ounce bottle of beer. Firecrackers burst, confetti and ribbons are tossed, and people hold up their hands in prayer.

The pebble-game fantasy world has a deep and long history in Andean culture—and is a ritual common to pilgrimages throughout the region. Making offerings and sacrifices to the Pachamama has always been an integral part of the lives of Andean Indians—a way to communicate with the pagan gods, and later the Catholic saints, to ask specific material favors and to offer thanks and praise. Playing with miniatures at Qoyllur Rit’i is one such form of an offering.

“When a pilgrim picks up a pebble at Qoyllur Rit’i, he is in a kind of world-defining situation,” wrote the anthropologist Catherine Allen. “To pick up a piece of the mountain in this time and place of potency and transformation is to pick up the world itself and form it in one’s own terms, according to one’s own desires and needs.”

- Ukukus carry their rope whips and wear ceremonial smocks adorned with brass bells. They also carry small bottles of alcohol around their necks—to help them stay warm inside on long freezing nights.

Pebbles were picked to represent alpacas, llamas, sheep, or cows, and then placed in miniature stone corrals. Bits of paper were exchanged as imaginary seeds and planted. Allen also explains that Andean rituals are defined by synecdochical thinking: “Small and large imply each other concretely; a powerful miniature informs the cosmos with its own form.”

But in the late 1970s, just as glacial melt began to accelerate, the pebbles at Qoyllur Rit’i began to change. During her second trip to Qoyllur Rit’i in 1980, Allen noticed that more of the miniature pebbles represented urban material desires than when she first observed the custom in 1975.

“There were fewer domestic animals and many artefactos—pebble sewing machines, refrigerators, televisions, and Volvo trucks,” she wrote. The modern world’s endless parade of shiny objects had made their way to the high Andes, starting in the city of Cusco and trickling out to the countryside.

Eduardo Laura is now chatting on his imaginary cell phone, a lump of granite.

“What’s that white thing?” I ask when he gets off the phone.

“That’s a flat-screen TV. Plasma,” he responds.

He brings the cell phone back to his ear.

“Eduardo, Eduardo, son, are you there?” he calls out. In the distance, a boy answers on his own rock cell phone.

“¡Hola, Papi!”

“Did the car arrive?” Laura shouts into the phone.

“Yes, it arrived today,” his son screeches back.

“Bring it over quick, son. Hurry, hurry! If you don’t hurry up, you’re never going to get business! Ciao, ciao, son!” The boy vrooms his rock car over toward his father’s fantasy empire of TVs and trucks.

- After three days of no sleep and nonstop dancing and prayer, pilgrims start their long journey home, with Mount Ausangate in the distance. Many don’t have the money to pay a bus fare and will walk for a day or more.

Weary from the altitude, the climbing, and from not having slept in forty hours, I call it a day and stumble toward my tent. Climbing in, I remember learning that there is no word for “why” in Quechua. If you want to ask a why question, you either try to find out, “For whose sake?” or “Who did it?” or you can ask, “What was happening at the same time?”

And so, I think about what’s happening at the same time back home in New York, where the trucks plying the avenues are real and the flat screens are plugged into the wall, sucking energy. We have a word for why.