In 2002, throughout the Sub-Saharan region, more than 40 million children were orphaned from AIDS, poverty, and political conflict. In Kenya alone, the count was over one million. While photographing in the streets of Kibera, one of the largest slums in Kenya, I witnessed the paradox of people looking for joy in the most difficult circumstances. I was told about two orphaned brothers who lived on these streets. The younger one, just eight, carried a small piece of clay in his pocket. For one shilling, he would sculpt the clay into any shape a passerby desired. One figure after another was created only to be smashed down again for the next request. His older brother, eleven, could turn scrap metal into small airplanes that could actually fly. The boys had gone missing and were feared dead.

I couldn’t help but wonder about the tremendous potential disappearing with lives such as these. I was struck by an irresolvable contradiction: an artistic desire to tell stories through images and a nagging doubt about the effectiveness of my own photography. Several years passed before I learned how to translate my Kenyan experience into something visual that would satisfy my desire to make a social impact, when I discovered the intersection between art and activism.

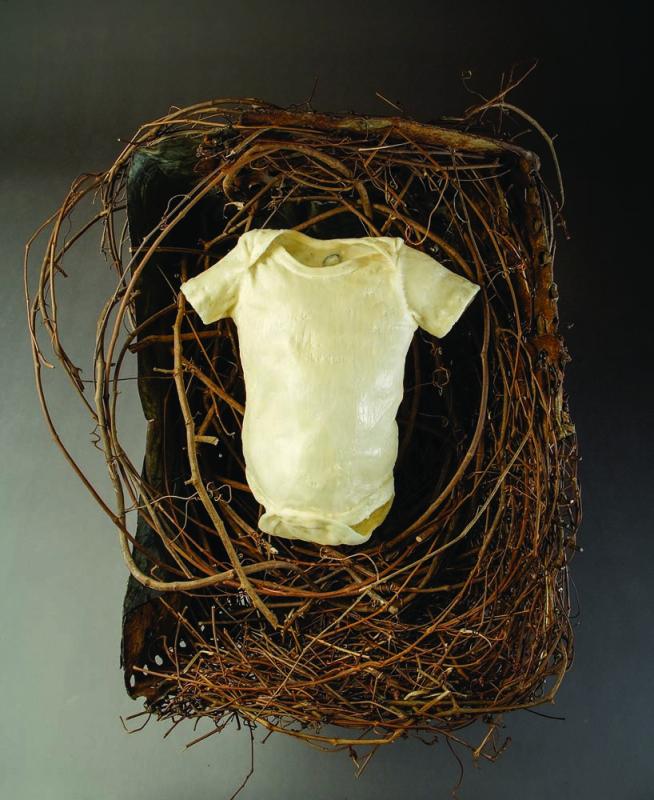

In 2006, I founded The Cradle Project, an art installation designed to call attention to the plight of millions of children orphaned in Sub-Saharan Africa. Its mission was to promote awareness and raise funds to help feed, shelter, and educate these children. The vision of the installation was simple and direct—empty cradles displayed against a backdrop of falling sand.

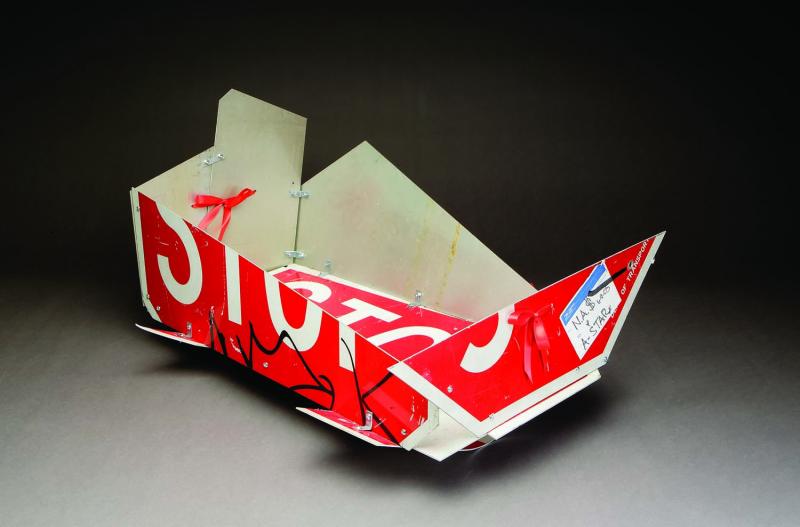

One cradle seemed hardly enough. One hundred wouldn’t be enough. To mirror the scale of this crisis, we needed overwhelming numbers. What’s more, the cradles would be made of found objects, such as Vincent Leandro’s cradle, which is made of discarded furniture. The metaphor seemed clear: If we can see potential in discarded materials, take a scrap and build a harbor for a child, then surely we could help realize the potential of these orphaned children. As Leandro wrote in his artist’s statement, “These familiar domestic elements are symbols of our everyday lives—of normalcy, stability, family, and home. They represent people and conditions we cannot imagine losing.” By project’s end, hundreds of artists came together to create 550 cradles, each bearing witness in its own way.

The inspiration for the One Million Bones project comes from Philip Gourevitch’s We Wish to Inform You That Tomorrow We Will Be Killed With Our Families, which documents, in haunting detail, the Rwandan genocide of 1994. It wasn’t until 1998 that the US officially recognized this tragedy for what it was. Nor had we taken action against it. I often wonder what kind of impact the bones of the 800,000 massacred would have if piled on the streets of Washington, DC In the face of such evidence, would there have been a call to action?

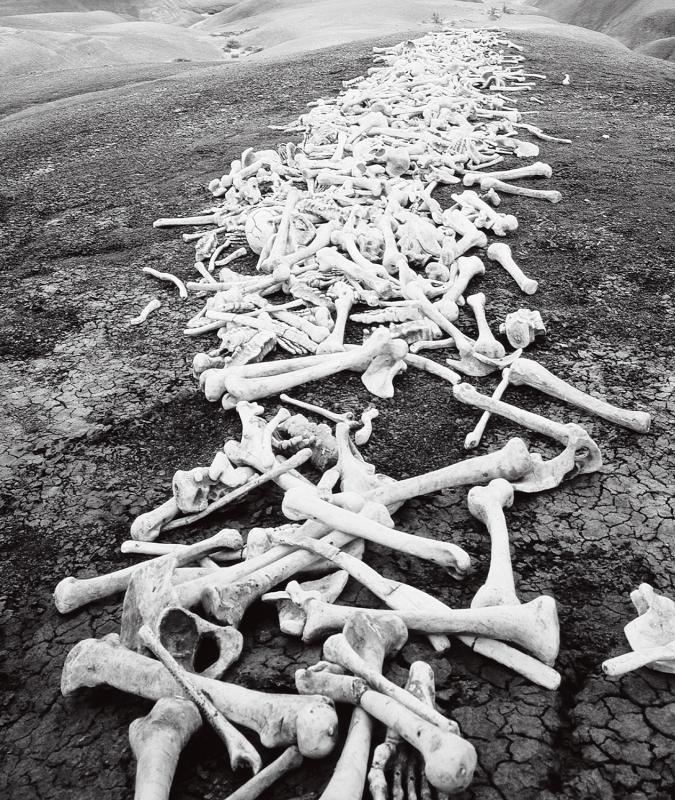

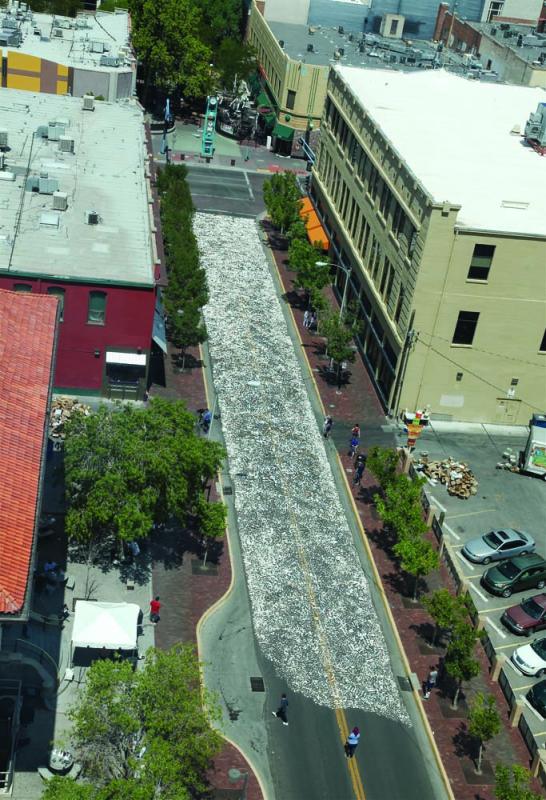

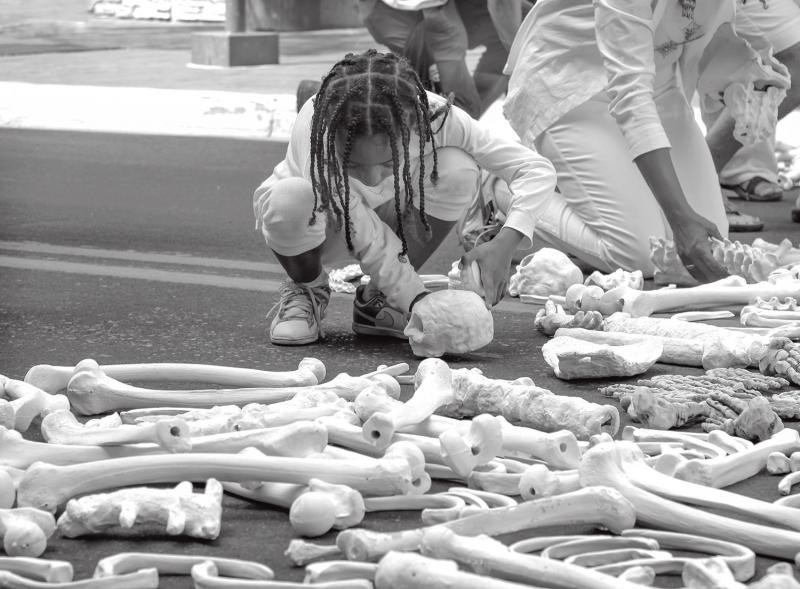

One Million Bones is a “social arts practice,” which helps raise awareness—through education, hands-on art-making, and public art installations—of the crises plaguing the Congo, Sudan, Burma, and Somalia. To this day, there is an astonishing lack of alarm over the atrocities being committed in those countries, coupled with a sense of futility or indifference among those in the US and Europe who do know. The project strives to create a “visible petition.” Each bone is a signature, a voice, a call to action. The project is also an educational process—about this issue, about civic engagement, about the power of the individual and art. Ultimately, it is a visible demand for a solution.

The bones being sculpted for the installation on the National Mall in June 2013 are representations of flesh-and-blood lives. Each bone attests to the gravity of unfolding political crises, to their human costs. But the bones are also significant as symbols of our human connection. This concept is crucial in the work we do. If I can recognize myself in another person, if I can begin to understand that we belong to one another, then I am responsible for that person. It is this essential principle of connectedness that moves us to action, and I believe art can take us there.

Last year in Albuquerque, New Mexico, we laid down 50,000 bones. One of our presenters, Kigabo Mbazumutima, was a refugee from the Congo, a survivor of the Gatumba Massacre in Burundi. About an hour after we started laying out the bones, Kigabo seemed overwhelmed. “You have to understand,” he said. “We lost so many people and we never saw what happened to them. We wanted to believe that they were okay. But I saw them today. We have to face it. Everyone has to face it.” The same month we laid those bones down in Albuquerque, three new mass graves were discovered in Sudan.

It takes a conscious commitment to fashion a human bone from clay or plaster, a higher commitment still to consider the depth of that symbol. I’ve made hundreds of bones in the course of developing this idea, but the bone that means the most to me is one I made with a Sudanese woman named Achta in mind. Achta, thirty, lives in a refugee camp in Chad. When I hold this sculpture, I’m reminded of life, birth, beauty, and their fragility. I’m reminded, too, of death and the thin line that separates us from it. I think of the four children Achta lost on her journey from Sudan to Chad. I think of her remaining five children, who work to earn a living in the refugee camp. This bone is my connection to Achta, and for me, the story of her children is embodied in it.

Given the scale of this project, it would have been impossible to do alone, even with the help of hundreds of professional artists. Instead, we visited classrooms and art centers around the world, enlisting tens of thousands of children and adults who brought their own skills to bear on the process, investing their compassion, and thereby adding their voices.

During the 1800s, New Orleans was a major port for the African slave trade in America. On Sundays, enslaved Africans would gather in Congo Square to drum and dance. You could hear the sounds reverberate throughout the city. There are many beautiful sites in New Orleans that would have been ideal for the installation of bones, but we chose Congo Square for its history, its beauty, and its heart. In April 2012, we laid down 50,000 bones to the sound of drumming. We laid them down for the people of the Congo, Sudan, Burma, and Somalia—and no less for the people of New Orleans. Laying the first bone is always a great honor, but a difficult task. We asked Mama Jamilah Yejide Peters-Muhammad, one of the Congo Square elders, to lay it in the center of the square that day. It took Mama Jamilah three attempts to make that short, overwhelming journey. Carrying the bone raised powerful emotions not only because of the history of her ancestors, but for the deep connection she felt to those victims so far away.

New Orleans is one of the most violent cities in the United States. When we introduced the idea of raising global awareness about genocide to kids in classrooms and community centers around the city, they got it—and on a much deeper level than I had anticipated. Many of them knew violence firsthand. They expressed an intimate connection to the violence in countries such as Sudan and the Congo. And they crafted bones to honor not only the faraway dead, but victims in their own families, in their own communities. On April 7, 2012, hundreds of them showed up to help lay 50,000 bones in Congo Square. I can only hope for the same dedication when we lay one million bones on the National Mall in Washington, DC, next spring.