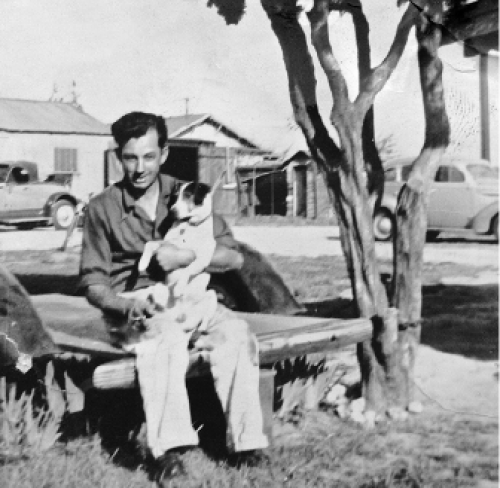

1937: He is a boy in the bed of a Model T pickup, the bed covered with a tarp like a square pitched tent, the back open to the road behind them. All their belongings are packed neatly in the bed, and the boy sits on a blanket on top of it all, beside him his new dog, a fox terrier puppy named Mickey. In the boy’s arms is his favorite book, The Wizard of Oz. He carries it with him everywhere, reads it again and again.

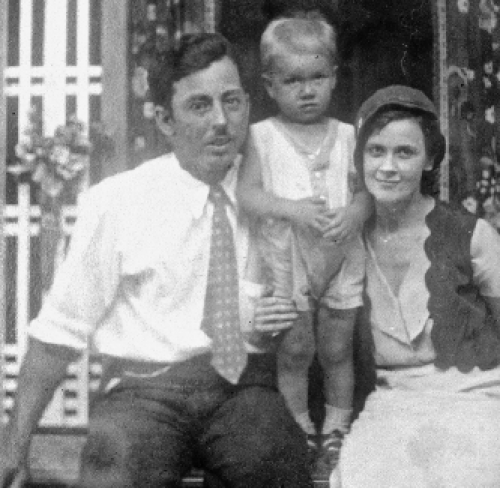

The boy is seven years old. He and his mother and father have lived in three cities by this time: Decatur, Illinois, where he was born and where they’d lived the last year, and Minneapolis, and Elgin, Illinois. Moving is something he knows about already.

The bed is open to the cab, his parents sitting on the bench seat up front. Sometimes he sits between them, but now he is facing the back of the truck, out there brown rocks and brush, bright blue sky, a strip of cement behind them with cars and trucks on it, following them like a kind of parade. He can see back there some old trucks like theirs, dusty, and dirty, packed full like theirs.

The difference is that their truck is clean, no matter how old it is. His father keeps it that way, takes care of it, hoses it off at every cabin camp they have stopped at. A long trip this has been. They spent a month in the cabin camp in Marshfield, Missouri, because his father had to pull the engine—he’d heard the word crankshaft again and again—and fix it after it broke down.

The truck isn’t even theirs. It was Grandpa Price’s, given to them after the accident. A few months ago his mother had been driving their own car, a Plymouth coupe, with Grandma Moran when a bumblebee flew in through the window. She’d tried to swat it out the window, and crashed the car into a concrete culvert. Her nose and collarbone had both been broken, which was bad enough—he’d seen the giant blue bruise of her face in the hospital—but the terrible thing was that his grandmother had broken her pelvis, and had stayed in the hospital for weeks.

His mother had felt terrible about his grandma, the boy knew. He’d seen how she’d cried after that. The car had been destroyed too, and because his father had needed a way to get out to the few jobs he could find—he was a sign painter—Grandpa Price gave the old truck to them.

Now they are moving to California because there is not enough work left in Decatur. There is not enough work, anywhere, even though his father is very good at what he does. The boy has seen the sides of barns his father has painted, colorful pictures and perfectly shaped words twenty feet tall. And he’s seen the Shell gasoline stations around Decatur his father had been in charge of keeping painted and clean, all of them sharp and bright. His father is good at what he does. But there just isn’t enough work anymore, he’d heard his father tell his mother a hundred times. There just isn’t enough work.

Last month his father’s brother, Uncle Roy, who’d moved out a year ago to Burbank, wrote that business was good, there were jobs to be had. Uncle Roy is a sign painter too, and Frank, the boy’s father, and his mother, Winnie, have told Frankie something good will come of their moving out there. Something good is coming for them.

It will be a lot like Oz, Frankie thinks. It will be green, certainly, and he knows there will be orange trees too, because he’s heard his parents talk about them. He’s heard all about California, knows already that this is where they make the pictures. He and his mother and father used to go to the pictures a lot—his parents even met each other at the pictures. He imagines they’ll be in a wondrous place once they get to California, that they will be able to pick oranges anytime they want, and everything will be green, just like in the Emerald City.

Now he feels the truck slow down a bit, and out the back he can see they have driven onto a bridge, the steel arc supports on either side of the narrow road rising and rising the farther out on it they drive.

He turns from where he sits with the book and with Mickey, the puppy pawing at him for his turning, and looks over the bench seat to see the bridge in full out the windshield: huge, steel, extending high above them and arcing down to the far end. He can see a river beneath them, and trucks and cars in front of them, and then they are across, and here’s the sign: Welcome to California.

The trucks and cars slow down even more, the line of them nearly at a standstill, and now Mickey begins to move around, excited at this change. They’d gotten him at the cabin camp in Marshfield, from a well-dressed man who used to come around in the evenings to the camp. The man was a gambler, Frankie’s father told him once while working on the truck engine. He was a nice man, always treated Frankie well, even showed up one day with this puppy in his arms as a gift.

One afternoon the gambler and his father took the dog back behind the barn at the camp and cut off its tail, the puppy howling for what seemed hours after that. At the next camp they went to once they left Marshfield, they’d gone into the manager’s office, Mickey with them. The dog hit his tail on a chair, let out a yelp at the pain, and the manager turned them away right then: No barking dogs allowed. From then on it had been Frankie’s job to hold Mickey whenever they were stopped somewhere, to keep him from bumping his tail again.

Mickey: named after Frankie’s favorite toy, a tabletop Mickey Mouse circus train and cardboard circus tent with a Mickey Mouse figurine, like a ringmaster over the whole thing. He’d gotten it for Christmas when they lived in Minneapolis, and one day not long before they left for California the family had gone on a picnic, Frankie bringing Mickey. Somehow he lost the figurine that day, his favorite toy gone, just like that. So he named the dog after Mickey Mouse, that best part of the whole circus.

The trucks ahead of them, the dirty ones packed up like theirs, are pulling off the road and onto the dirt shoulder now, one by one. He can see past them a big building ahead off to the right, beside it a high and huge metal awning, like a giant garage with no walls and open to the air, and now, with these trucks pulling over, he can see a man in a uniform in the middle of the road, pointing to one truck, then another, signaling each one to pull off the road.

His father inches the truck closer to the man in the uniform, a policeman, Frankie sees, with a gun at his belt and a cap with a shiny bill.

His mother picks at the pleat in her slacks, folds her hands together, lets go and smoothes out the material, folds her hands together again. His father holds tight the steering wheel.

They have come this far, they have been on the road to California all these weeks. They are in California, so why do they have to stop?

Then the man in the uniform is in front of them in the road, hands on his hips. He tilts his head one way, looking at the truck, Frankie can see, and the man steps to the left, motions for his father to pull up to where the man can talk to him. Frankie’s father slows down and stops beside the man, looks out at him, still with his hands on his hips.

“Transporting any fruits or vegetables?” the man in the uniform asks.

“No,” his father replies.

“Where you headed?” the man asks next.

“Burbank,” his father answers. “My brother lives there.”

The man pauses a second, looks back and forth at the truck as though it were something dead, his mouth clinched tight.

“Go on through,” he says and takes a step back, points his finger and wheels his hand at the wrist, already looking at the truck behind them.

“Thank you,” his father says, and they move forward, the road before them clear and empty, all the others pulled off on the side of the road.

Slowly they drive past the row of trucks, and up near the head of them all, almost to the big building and that giant awning roof, Frankie sees people washing their trucks, cleaning them of all that dirt. And there under the awning are more and more trucks, some of them emptied of everything, boxes and suitcases and chairs and quilts all spread out around them, all filthy. He can see kids out there, too, dirty as their trucks, and mothers and fathers all standing around or washing their trucks or packing things up or taking them out. He sees rows of washing machines off to the side of it under the awning, fifteen of them, twenty, all with a woman or two or three standing at them and either bent to the washboards inside them and scrubbing, or feeding clothes through the wringers above them, while even more kids, some older than him, some younger, stand beside the women or play chase with each other or just sit, waiting.

They got through because their truck is clean. Because his father has kept their truck, this old Model T, free of dirt.

He turns and looks out the back of the truck, at all the dirty trucks, and all the women washing clothes, all those kids, and there seems something strange and something sad about what has happened. And he is relieved, too. But there is something wrong, he sees, in what they are making those people do just to get into California.

His family has made it through because his father has kept the truck clean. That’s what it takes to get into California?

And then he thinks: California! He turns and looks out the front again, to that open road. He sees in the cab his father turn to his mother, a smile on his face, and he sees his mother give a quick shrug. She’s smiling too, and she pats his knee, and he knows what that means: They have made it. They are here, and something good is coming.

He looks out the windshield then. They are in California, they are here.

But all he can see are brown rocks and brush. The same desert they have been riding through forever.

Where is the green? he wonders. Where is all the green he’s heard about? And where are the oranges?

This place, this desert, this is California?

1981

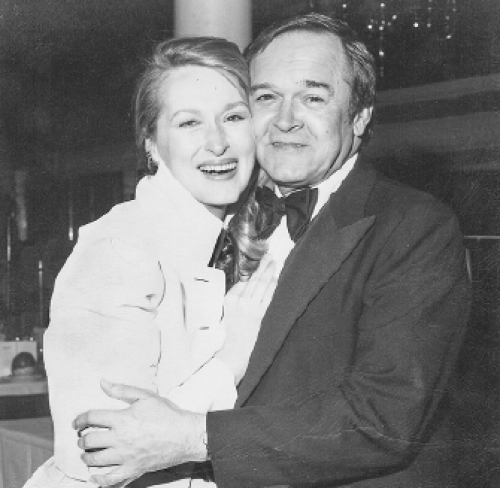

The actor is a phenom, a supernova. A force to be reckoned with.

But he is definitely troubled, Frank can see. He’s overweight, and sweaty, and an hour late. And the picture he’s just completed—it will be released in less than two months—might very well be a failure. A troubled picture with a troubled star.

Now here’s John Belushi in Frank’s office at Columbia Pictures, ridiculously animated, smelly, hair and eyes wild. He’s here to lobby hard for the closing tune to the picture, a picture that has had problems since the first day of shooting, and even before that.

When Bernie Brillstein, Belushi’s manager, had called Frank yesterday on behalf of the producers of the film, Dick Zanuck and David Brown, he’d asked if Frank might set aside a few minutes to meet with Belushi and listen to the tune Belushi wanted to put in the picture. Belushi is obsessed with the band who plays it. It’s this new Punk music, Brillstein told him, the band’s name Fear. Belushi has a friend in the band named Derf Scratch. Derf: Fred, the real first name of the band member, spelled backward.

Beyond that, Brillstein wouldn’t say why Frank had to meet with him, why this meeting was so important. But Frank knows why: No one of any measure involved with the picture wants to say no to Belushi.

Because Belushi wants the tune in. The phenom, the comet everyone in town wants to grab hold of, and everyone in the theaters wants to watch.

Frank can meet with him.

Frank is the head of the studio, appointed president three years ago and then chairman and CEO earlier this year. It’s been a long time getting here, to this very nice office. Until he arrived here and had been given the job of making pictures, he’d worked entirely up through the ranks in tv, beginning back at CBS in New York in ’51, when he’d started out as a reader and story analyst for the old days of live drama. Opening mail, reading scripts, synopsizing them, and writing his critiques. He’d been a writer through it all, focused always on the story to be told, even when he’d been producer for The Virginian and the studio head who’d put together Rich Man, Poor Man, even when he and Lew Wasserman and Jennings Lang had developed the whole idea of the made-for-television movie, Frank eventually becoming head of Universal Television. He’s a storyteller first and always, even here, in this office. The head of Columbia Pictures. It’s the story that matters.

He’s also a kind of fixer, a man who can calmly herd various creative—and therefore sometimes unreliable, sometimes volatile—entities into making projects that might work. A levelheaded, sensible man who listens, ruminates, then makes thoughtful decisions based on practicality tempered with a shrewd intuition. It’s how he did so well at Universal MCA with his string of hits—Ironside, The Rockford Files, The Six Million Dollar Man, a dozen more. This ability is one of the primary reasons he was brought on to head Columbia in the first place, after the David Begelman catastrophe, the scandal that stupefied an industry rife with scandal to begin with. But it’s also his ability to spot a good story when he sees one. He is here because he knows what a story is, and because he is a cool hand, and can get things done. He holds things together.

Begelman. A stunner: the president of Columbia Pictures caught forging a $10,000 check made out for expenses to Cliff Robertson, the only actor in Hollywood who cared enough about integrity to blow the whistle when he found out what had happened. It had taken Columbia’s board of directors in New York a year to finally work up the guts to fire Begelman, but the hole he’d left made room for Frank.

He’d wanted into pictures. Everything before this had been television. But television, even if he was president of Universal Television, was still television. It wasn’t the movies. And then had come a call from his friend Leonard Stern, producer of McMillan and Wife, who told him he’d talked with Dan Melnick, the acting president of Columbia now that Begelman was gone. Stern had told Melnick good things about Frank, and next came the call from Melnick himself to tell Frank he’d heard about how he could keep things calm, about the fine work he’d done putting out all those tv hits. Did he want to come to New York to talk to Alan Hirschfield, president and CEO of Columbia Pictures Industries, the parent company of the studio, about coming to Columbia?

Did he want to head the studio?

And then he’d found himself out for dinner with Hirschfield himself at Christ Cella, the old steakhouse on 46th and Lexington. Meeting at Columbia’s corporate offices at 711 Fifth Avenue was out of the question: If anybody saw Frank Price walk in the front door, the trades would have the news headlined the next morning. They’d had dinner, talked, and talked. Hirschfield had liked him; he’d liked Hirschfield; deal done.

Frank would make pictures. Though he’d been in the industry for more than twenty-five years, it’d felt like he was starting all over again.

But what hadn’t been any different from television, he’d found, was that some actors brought along whole steamer trunks of issues. Belushi was something of a known hazard walking into production, a loose cannon. The problem might have been drugs, but Frank couldn’t know for sure. Drugs were often the problem. He’d even had a rough patch himself, back in ’60, when he’d spend all day every day story-editing for The Tall Man, a series for Revue Productions based on the lives of Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, then worked the weekends developing the next series down the line. Before that, he’d worked himself to the bone on The Rough Riders and Lock Up at the same time, both for Ziv-TV, the scrappy production company that burned through series with a mind to throw stories at the wall and see what stuck. He’d gotten a prescription for Dexamyl to get him through the night so that a script could be ready for shooting the next day, but then one night he’d found he couldn’t write without it. That was when he’d quit. He’d done it. Quit. Because the story—and his ability to see clearly—was what mattered.

Belushi was supposed to have been here at ten, but hadn’t shown. Nothing Frank didn’t expect. He’d worked with creative people most of his life, and found some to be punctual, but many more late. Then, a little before eleven, his secretary had come in, told him there was a limo parked out on the plaza. It had been there almost an hour, right out the front door. They thought it might be Belushi, but no one had the nerve to find out.

Frank stood, moved from his office to the outer office and into the hallway, walked out to the plaza.

There sat a limo.

Never act surprised at anything, he knew. Act as though everything is fine. Things he’d learned from growing up with his mother, helpful tools he’d discovered to edge his way through the troubled life she’d lived since he was a boy, and that he and his father had had to live through because of that trouble.

His parents were still alive, still married, despite everything. Living back here in California. They’d seen him come up through the whole machine, seen him take his place in this business. And though meeting a young star’s limo hadn’t been what he’d figured a part of the deal, he would do it. This was the story, the next move to be made, the next line.

Never act surprised at anything. Act as though everything is fine.

Frank had bent to the door, opened it, and said, “Hi, John! Won’t you come in?”

Belushi had been startled. His eyes were glazed, the T-shirt he wore sweaty, his face unshaven.

Frank had put out his hand for Belushi to shake.

Now here he is, searching Frank’s inner office for a stereo system. Why doesn’t he have a stereo system in here? Belushi wants to know, talking too fast and too loud. Then he rails on about why he’s late, how he thought he’d have to find a cab because the limo was so late. He has a cassette tape in his hand, Frank can see, and he is looking for a stereo system, and he is troubled.

Frank has seen the first audience responses for the picture, screened a week ago on the lot to a bevy of studio execs and a few hundred Belushi and Aykroyd fans. Of course he’d hoped for something good: The halo the public had set over Belushi since Animal House and The Blues Brothers, not to mention Saturday Night Live,still hovers over everything Belushi does. He is a bona fide star.

But the numbers on the screening are awful. Frank has never seen worse. He’s viewed Neighbors twice already, once for the rough cut two months ago in August. The film had been funny then, so funny some of the execs at the small showing had laughed so hard they’d drowned out parts of the dialogue. The soundtrack had been a temporary one, pieced together from old horror movies, just as filler for the black comedy. And then Frank had seen it the second time, at the screening last week when they’d passed out the preview-response cards.

That was when he’d known it might be a disaster. The crowd hadn’t laughed, the completed soundtrack had been strange, and his initial misgivings about doing a black comedy had been correct.

Frank knows some pictures are good, others bad. An important factor in doing this one in the first place had been that Dick Zanuck and David Brown were the producers, the duo who’d put together The Sting and Jaws. Frank hadn’t yet worked with them, and here had been the chance to develop a relationship with two of the best producers in the industry. Even though Frank knew the production had been difficult from the first day of shooting, when Belushi had started up with his tantrums at the director, John Avildsen, who Aykroyd and Belushi both thought clueless about comedy, the picture was still an opportunity for the future. A kind of investment, both in the team of Zanuck and Brown and of course in Belushi too. There was always another picture, a better one, coming around the corner. But right now there was only one Belushi, and he wanted Frank to listen to a tune.

So far as the head of Columbia he’d put together what had turned out to be a good string of hits. There was the surprise of Stripes, with one of these Saturday Night Live newcomers, Bill Murray, and the $80 million it’d turned in. There’d been Stir Crazy, with the hottest comic in the world, Richard Pryor, and Gene Wilder too. His friend Sidney Poitier directed that one, and the gross looked like it might one day hit $100 million. Just this year they’d put out The Blue Lagoon, and though it cost only $4.5 million, they’d made back ten times that.

There had been Kramer vs. Kramer, and its sweep of the Academy Awards last year, winning five Oscars. Though Begelman had started the ball rolling with that one, the picture had come through under Frank’s watch; it had been twenty-five years since a US-produced Columbia picture had won more than one Oscar, and wins like that meant everything.

But this picture. This picture.

They’d shown Neighbors in two rooms; in one room, only 1 percent rated it excellent; in the other, 2 percent. Fifty-six percent thought it “Poor (One of the worst movies I’ve ever seen).”

Perhaps the whole thing can be salvaged, Frank believes. If he can coordinate a couple of strategies, one being to release it in as many theaters as possible at once right before Christmas and to do so before any reviews hit the street, then things might work out. Money might be made. “Hit and run” was what that strategy was called, an old Hollywood idea, but one that sometimes worked.

The other strategy involves the story the picture tells. It isn’t funny, for starters. Maybe a prologue of some sort could be used to set up viewers’ expectations for a dark comedy. Maybe viewers could be told what they were about to see was a comedy.

And the ending doesn’t work, Frank knows. The ending has to be changed, because no one goes to the movie to see Belushi lose. Nobody goes to the pictures to watch Bluto or Jake Blues end up in a hole.

The story matters, Frank knows. It’s the story.

Frank leads Belushi back to the outer office now, then out into the hallway, looking office by office for a cassette player, until finally they find a cheap plastic one—a “boombox,” Frank knows it’s called—though Belushi complains its speakers are too small. They go back to Frank’s office, where Belushi pops in the cassette, hikes the volume up as loud as it can go. Now Belushi—even sweatier now, even wilder—is dancing to the tune, if it can be called that.

It’s noise. Nothing more.

What does Frank think? Belushi wants to know, still dancing.

Frank has to shout he thinks it’s good, but he’ll have to hold off on a decision as to whether or not to use it for the picture.

Why? Belushi pushes. This is the new music, this is the music everyone listens to.

Frank doesn’t think this is true, but he holds back. He’s being practical with this issue—the music is dreadful, angry, unintelligible—and now that shrewd intuition kicks in: If he says no outright, he might tip Belushi in some way that will destroy whatever good can be salvaged from the picture, and any more Belushi might make for Columbia in the future.

Of course the music won’t go in. But he’d listened. He’d done that for Belushi, this sad and poisoned young man who looks to have more talent than he can live with. And he’d listened to it for Brillstein and Zanuck and Brown, taken a kind of grenade for them so that the final decision—the final no—can be hung on Frank, and not them.

He’ll have to think about this, he tells Belushi.

The band will work hard to promote the picture, Belushi says over the music. He’ll get them on Saturday Night Live to sing it.

He’ll have to think about this, Frank says. He’ll let him know.

Belushi, as though finally listening to his own intuition, stops dancing, turns off the music and retrieves the tape, then leaves. He understands, Frank knows.

Frank has been the careful firewall against the comet, the phenom. He has honored the picture’s producers. He has done the studio a great good in holding this brittle thing called a picture together, though the picture, no doubt about it, is a disaster.

About the ending, he thinks, and returns to his office. What can be done for the story?

1944

He’s done with the assignment—sentence parsing, an exercise that takes every bit of life out of a sentence, makes the story a sentence tells look more like a frog dissected for Biology than anything like a story, like something happening—and sits staring out the window. Five minutes left to the end of Mrs. Gentry’s English class, and the rush of everyone standing up at the bell, then passing by the teacher’s desk to turn in the exercise, the push then to the next class at Bearden High.

Mrs. Gentry is his favorite teacher, this his favorite class, because when they talk about books, and about short stories, and about poetry, he can tell what she teaches matters to her. She is younger than his mother, and pretty. And she is kind, he’s already seen in her eyes.

Five minutes. Five whole minutes to the end of class. And so because he has this empty time, he does what he does a lot: He runs through all the places he’s lived, counts them off in his head like a list of far-off relatives he might be expected to remember.

Elgin and Decatur (three times), Illinois; Minneapolis, Minnesota; Glendale, California; Texarkana, Texas; Provo, Utah; Ventura, California. And now here: Bearden, Tennessee.

He’s fourteen, and this is the ninth place he’s lived. His father has gotten another contract, this time in a place called Oak Ridge, working as an electrician for the war effort. Everyone here calls him a Yankee, which is the most ridiculous thing he’s ever heard. He’s from Illinois, if he can say he’s from anywhere. Yankees are from New England. But they just call him that, he knows, because he’s not from here.

Being the new kid has taught him how to get along with people, how to make friends. But it’s also taught him, not because he wanted to, but because he has had no choice, how to remain a little outside, how to keep a little close his thoughts and words.

After they’d moved to California the first time, his mother had gotten a job as a waitress at the Warner Brothers studio commissary in Burbank, and used to come home with stories of the stars she’d served. But his dad couldn’t find work, no matter what Uncle Roy had told him about jobs out there. First they’d lived in the travel trailer on Uncle Roy and Aunt Pearl’s lot in Burbank, then rented a nothing place out in Glendale, where his father had taken cardboard boxes he’d found, flattened them, then nailed them to the bare studs and painted them, made them into walls to try and turn the place into a home.

Two years later his dad still hadn’t found enough work, and decided to move back to Decatur, taking Frankie along. His mother would stay; she had a job at the commissary and could live with friends she’d made.

But after a year back in Decatur, his father still couldn’t find anything meaningful—he’d paint a sign now and again, do some electrical work, but not enough to live on—and Frankie’s mother had come to Illinois to get Frankie, bring him back to California while his father tried to sort things out. She’d saved enough money by then to move into her own apartment, even bought a car, a ’35 Ford, so she could drive to work. Moving in with her made sense.

His mother loves Frankie. And she loves his father. Frankie knows it. But his life is complicated. Too complicated for a fourteen-year-old. Too complicated even to think about.

While his father had been alone in Decatur, he’d made a decision about his life: He wanted to be an electrician. He’d studied, gone to Joplin, Missouri, and passed the exam to join the union, got a job in Mineral Wells, Texas, then another in Texarkana. Frankie’s mother worked hard in California, too hard, Frankie knew: Days she spent at the commissary at Warner Brothers, and nights she worked delivering food out to the soundstages for those pictures filming late, Frankie staying with friends instead of in the apartment alone. Then, toward the end of their time out there, his mother had come down with pneumonia from how hard she worked. That was when his father had set up in Texarkana, and Frankie and his mother moved out to be together, finally. When that contract ended, they moved one more time to Decatur, then back to Glendale, then on to Provo, and then back to California, where they lived in Ventura.

Too complicated. But not only for the moves, all the moves.

No.

His life is complicated because of the way his mother behaves. It’s complicated for the way she’d changed, starting when they were back in Decatur, and on into right now. The way her life for the last couple of years has moved in waves, from highs to lows, over the course of months. For weeks she will be loving and smiling and believing there is no limit to the money she can spend or to the glory their lives will be, and then will come the slow fall into darkness, the melting into tears, the forgetting to fix dinner or wash the clothes, the long naps that last into night.

When she is at the bottom she hits Frankie’s father. She tears things up, breaks plates, yells. When she is on the highs she will hold his father close and tell him how much she loves him, take Frankie to buy him expensive clothes, fix them special dinners. She’s the happiest, most loving person he’s ever seen, but when she is low he will come home from school to find her at the kitchen table, her head in her hands.

He knows his parents love each other, and he knows too that they love him. But he wants his parents to get along. He wants not to have this life of not knowing how his mother will be. He wants to count on something certain, something stable. And he wants to live somewhere long enough to believe he can call it home.

He wants the family to be together, and not apart, like it always feels when his mother is on her swings one way and the other. He wants them together, because he knows what it means to be separated. He knows what it means to be apart, from when he’d lived with his mother in Glendale, back when his father stayed in Decatur the first time.

Sometimes she brought him to work at Warner Brothers, the two of them driving in from Glendale to Burbank to the parking lot, then walking through the gates and onto the lot like they were important. His mother knew people and nodded, said hello as they walked between the huge warehouse sound stages to the commissary. And there had been the stars: He’d seen James Cagney and Carole Lombard and Ann Sheridan and Paul Muni, and dozens more.

Once, he’d been let onto a soundstage proper, and not just any soundstage but one of the special ones used for scenes at sea. The whole soundstage was flooded with water, a giant indoor tank set up for filming. Scaffolding all over, above it lights and cameras and boom mics, and what seemed a hundred people moving everywhere, working and working. He’d gotten to stand on the deck of a ship built for The Sea Hawk, a picture that’d come out the year before starring Errol Flynn, and had watched from there as the crew filmed a second ship across the water, this one built for the new picture, The Sea Wolf.

The shot was a close-up of Edward G. Robinson, and involved men working machines that sent out fog over the water and across the deck of the ship. He’d heard the words “Quiet on the set!” shouted out, and then, quieter, “Action!” and watched through a network of ropes and cables and lights a man in a black slicker and black cap standing at the ship’s wheel, hands on the handles and turning it just so, lifting his chin a little as the camera moved in on him.

Then it was over. But he’d seen it. He’d watched a movie being made, and when he and his mother went to the picture when it came out, here had been that moment, Edward G. Robinson’s face up there on the screen, to the left and above him a wisp of that fog, his hands turning the wheel, the camera coming in close. He’d been there!

He’d seen things. He had stories he could tell these kids at Bearden High, stories about Hollywood and living out there that he could use to entertain them, make some of them like him. He could do that.

But he wouldn’t be telling anyone about his mother, or about the way she beat up on his father, and how his father held her arms to keep her from hurting him.

And now, though they all live in the same house here in Bearden, Tennessee, there are still whole weeks when it seems they are separate. He wants the family together.

The bell rings, and they all stand, bustle toward the head of the room and Mrs. Gentry’s desk, where each exercise is turned in, set in a pile.

Frankie edges up to the desk, one of the last students out, and places the sheet on the pile, and looks at Mrs. Gentry, gives a quick nod.

“Frank,” she says, “would you please stay after a moment? I need to talk to you.”

He’s startled, stops, blinks. “Yes, ma’am,” he says, and one student and another, another, pushes past him for the door. Then he is alone with her, standing before her desk. Any moment now a flush of students will pour in for the next class and see him here before the teacher’s desk, wondering what he has done to merit staying after.

He watches as she pulls a folder from beneath the stack of papers, opens it and draws out a single sheet of lined paper, and he can see already it is the poem he wrote last week, then had given her to read for no other reason than he knew no one else to show it to.

He’d never written a poem before. But something in the class, and all the talk about words, and meaning, and story, had made him sit down one night and write it. Then he’d worked up the nerve to give it to her the next day.

He’d written about moving. “Driving Along on the Road at Night” was the title, and first line.

“Frank, I want to make a deal with you,” Mrs. Gentry says, and looks up from the poem. “You have written something special here, and I have seen the caliber of other work you have turned in. I am willing to take you out of the normal curriculum and, if you are willing, have you continue to write for me. I will also give you separate reading assignments. You do like to read, don’t you?”

“Yes, ma’am,” Frank says, and swallows hard, astonished. He blushes a moment, looks down at his feet. He feels his face flush, the heat a surprise. For a moment he’s embarrassed for the attention, and for what he’d written about, how closely she’s seen into his life. The poem is about moving, because that is what he knows about. Driving along on a road at night. His embarrassment changed into a kind of happiness: He’d done something good. Good enough for him to be noticed by the teacher. Good enough to get him somewhere past the assignments everyone else would get. Good enough to let him have to write, and to read. This teacher had seen into his life, and liked how he’d written of it.

All he’d done was to write a poem.

Of course he liked to read. Since before he’d ever gone to school, starting back when he’d toted around that old copy of The Wizard of Oz. Of course.

“Then we’ll begin with this,” she says, and sets down the poem, then pulls from the folder a blank sheet of paper, writes something at the top. She hands the paper to him and says, “Ivanhoe, by Sir Walter Scott. Please go to the library and check it out. Once you have read it, we will move on.”

He takes the piece of paper, smiling at the gift this is, then looks up at Mrs. Gentry.

“Thank you,” he says.

“I want you to write more poems,” she says, her hands folded on the desktop, “but also short stories. And there is the school newspaper, for which I hope you will consider writing.”

Writing. He’d never thought of that. Writing.

“Yes, ma’am,” he says, and, “Thank you.”

Writing.

The door before him bursts open, a flood of students for the next class. But Frankie simply maneuvers through them on his way out, his eyes on the poem.

1958

The budget for this episode of The Rough Ridersis next to nothing. Like every episode.

He’s at his desk at Ziv-TV, reading through this week’s script yet again, the sheets of paper spread across the desk. He’s the story editor, which means he’s the guy who gets to find ways to make both the story and the budget work. Both of these, at once. But most important is staying within the budget. He wasn’t getting another dime out of Ziv.

That’s how John Sinn, Ziv-TV’s president out in Cincinnati, made the whole production company work: Here’s a series we’re putting into production in the hopes of syndication, here’s how little we’re paying for it. Period. It was Frank’s job to figure out how to pull it off, come hell or high water, for better or worse. Look closely at Highway Patrol, one of the string of hits Ziv had—there was The Cisco Kid, Sea Hunt too—and you’d see Patrol was nothing but a couple police cars, a couple motorcycles, some weedy exteriors on a blacktop side road out in the Valley, and Broderick Crawford gravel-talking into a police mike. Yet it was a hit, because it was a good story: a police drama about good against evil, a narrator to make it sound a little like a documentary, and all of it set on the highways and byways of some unnamed state out west. Nevermind the budget didn’t allow many car chases or wrecks, even if it was about the highway patrol.

But The Rough Riders was different, though not in budget. Every other Ziv production so far had been sold for syndication to local broadcasters across the country, channels that filled their time with these cheap productions. The Rough Riders, though, was the first Ziv program to be sold to a network—ABC—and though it showed no signs of being a hit, still, it was work, and Frank was glad for it, despite the exhaustion every night. Each day he was here at his office, the six soundstages taking up a whole city block on Melrose, and working on the script either with the writer or on his own, trying to tighten it, finding ways to save money and how to give a good, solid story. And every day he was out on the set supervising dialogue, talking things out with the leads and bits both. Late afternoons he was looking at dailies, piecing together the story with the editor to make it look right, to make it tell right. Because the story mattered most.

Then, at night, he was back here in the office working on a new pilot Ziv was getting into production, a project called Lock Up, a law drama that set as rivals the attorney and a police detective on the case for that episode. Evenings were given over to developing and research and writing and developing and writing.

Some days he worked eighteen hours. Some twenty. But he was working.

As with every other Ziv production, the reason The Rough Riders needed to be worked through so deeply with the actors was because there was no story. Only a situation, like the idea of Patrol: a weekly pitting of the patrol against bad guys. The Rough Riders had absolutely nothing to do with Teddy Roosevelt; it was a post–Civil War story about three men headed west, two of them former Union soldiers, the other a former Confederate. The rules he had to work within were tight, and were never to be broken: (1) there would never be any mention of how or why these three men knew each other, how they met, no backstory at all. Backstory meant extra dialogue, when the series couldn’t afford such frivolities as too many words. And (2) the program had to be shot interior as much as possible, on a soundstage at Ziv. Though exteriors were necessary—this was a Western, after all—they were also expensive, called for the export of equipment, extra time for lighting, horses trailered to the location, not to mention transporting the entire cast and crew.

But even the interiors, because of the budget, were stripped to nothing, each episode set at a crossroads somewhere, no town anywhere. The intrigue or romance the three men—the rough riders—ran into all occurred in the middle of nowhere. The most the budget could afford was a general store now and again, at that week’s crossroads. But otherwise, nothing.

He pores over one sheet of the script, looking, then picks up another, and another. The script spread out in front of him on the desk is a kind of jigsaw puzzle made of dollars and words, his job to make them both fit into the format that will be this week’s story.

Then he sees it: the quibble, the blemish, the niggling twitch of the tightrope walk between story and budget. The episode had been written to include a gunfight at the crossroads, in which the villain, mounted on horseback, gets shot out of the saddle.

A problem.

Falling out of the saddle calls for a stuntman, which calls for an extra couple hundred bucks out of the budget.

But the story is right. The villain is on a horse, has to be. He can’t dismount, he can’t get away. He has to be shot, and has to be on the horse.

And Frank has to make the story and budget get along. He has to make it work.

He takes out his pencil, leans over the page, strikes out the line in which the villain is shot out of the saddle, and writes above the typescript, “stays in the saddle, slumps forward.”

He’d done it a dozen times already, this quick and cheap fix. Sometimes he was afraid The Rough Riders might be remembered, if anyone remembered it at all, as the Western in which the most villains died in the saddle.

But it works. The story and budget, together.

He eases back from the desk, feels a twinge in his neck, his eyes hot for all this reading, all this searching. He’s tired, has been for months, working on these two projects at once. He’ll be up late tonight, too, looking at the next two scripts down the pike, studying, marking up. Reading.

He’s heard about some new medicines out there, prescriptions to help you stay awake. He could use something like that. Who knew when he’d get to bed tonight.

Pencil still in hand, he leans over the desk again, reads again these pages. This story.

1986

They’ve already won five tonight. This next one seems to Frank a sure thing, though he knows you can never count on anything. Never.

Barbra Streisand tears at the envelope, then says, “And the winner is, Sydney Pollack, for Out of Africa.” The score swells immediately, and Sydney, a row down and a couple seats away, is up and in the aisle and up the stairs.

He’s smiling, astonished, Frank can see. He accepts the Oscar from Barbra, holds it, looks at it, then says, “Thank you very much. Frank Price made this film possible. He had the courage when it mattered the most… . ”

Sydney goes on, about Kurt Luedtke and the script, about Meryl and Robert and Klaus, about all the others.

He’d heard his name spoken from up on the stage at the Oscars before. Dickie Attenborough had named him when he’d taken Best Director for Gandhi in ’83, and Stan Jaffe had thanked him back in ’80 when Kramer vs. Kramer got Best Picture.

But there’s something about this time, his name, the words, his friend Sydney humble and aghast and funny all at once.

He knows that most all—the overwhelming majority—of those people watching all over the world have no idea, and probably never will, who Frank Price is. His name is only two words spoken in a rush of them by the director, the one the world sees, like the actors and actresses honored each year, as the real winner.

That isn’t what matters, his not receiving one of these gold eunuch statuettes up there on the stage. He’ll get one on behalf of the studio in a couple weeks once it’s been engraved, and set it up in the trophy case at the office. Being up on stage for all the world to see isn’t what matters.

What matters is the fact he’s brought possibility to them all, the possibility to make something good. And there’s the industry recognition, his peers seeing that product as having worked, and being worthy. Not to mention the money this would bring in for Universal.

Out of Africa is a good picture. A great one.

They’ll win for Best Picture tonight. He’s sure of it.

1937

They are driving into Hollywood to see what they can see, Frankie in the bed of the Model T truck, still loaded with all their belongings. He’s holding The Wizard of Oz, and Mickey is back here with him.

They’d made it into Burbank and to Uncle Roy and Aunt Pearl’s house late afternoon—they would be staying in the travel trailer out at the far end of the lot—and then had some cold sandwiches, talked about the trip while they sat in the front room of his aunt and uncle’s house. Frankie could see by how his aunt treated them, the way she wouldn’t quite meet his mother’s or father’s eyes, that she wasn’t too happy with the arrangement. But they were here, finally.

And then, because they were finally here and because Hollywood is just down the road, and because his parents love pictures—they even met at the pictures—and because this is where they make them, Frankie and his mother and father climbed back in the truck, and headed on in.

Now they are driving along a wide city street, the sun down, the sky a dark pink out the back of the truck. There’s a big building out there, taller than any he’s ever seen, high atop it the lit block letters The Broadway, beneath that in smaller letters the wordHollywood, but all of them huge, way high up there.

There are cars everywhere—shiny ones even cleaner than the truck his father’d washed down when they arrived at Uncle Roy’s—and palm trees planted in the sidewalks beside the street. There are lights and buildings, and now as they pass an intersection he can see the street signs for the street they are on and the one they are crossing: Hollywood and Vine.

This is Hollywood, Frankie thinks. Somewhere around here is where they make the pictures.

And now a car, a shiny one with no roof and open to the air, is driving along behind them. Frankie looks at the car hood, sees in its shine the reflection of all these lights, then looks past the hood to the driver, a man, and a woman seated beside him. They are well dressed, he can see, the man in a suit and tie, just like in the movies, the woman with blond hair and leaning into the man.

They are laughing, he can see, and the man points at the truck.

Frankie turns to the front, Mickey still in his arms, and looks over the bench seat, sees his mother and father up there, looking at the lights of this wide street. Then he turns back, looks out at the driver behind them, there in his suit and tie, shaking his head hard, and laughing, the woman beside him laughing too.

They’re laughing at the truck, Frankie knows. They are laughing at us, because of this old truck.

The car speeds up then, passes them, behind the truck the lights of Hollywood Boulevard again. All these lights.

It doesn’t matter if people laugh at them, Frankie knows, because the lights here are beautiful. This place really is like Oz, like the Emerald City, only with lights of all colors, more lights here than he’s ever seen.

To his left he sees now the neon word pantages in rounded-off square letters running down the side of a building, and on either side of the street are lights in store windows and restaurants, and lampposts cast bright halos on the sidewalks everywhere. Lights, everywhere.

But above it all he can still see the sky out there, perfect and clear, a deep orange now and growing darker.