Reporting on the oil crisis in the Amazon, Kelly Hearn contributed an essay and photographs to our summer issue. “A Jungle Tiananmen” delves into the multilayered interests that underpin a brutal protest in Bagua, Peru, in which the native community faced off with paramilitary police over land reforms. Hearn is a correspondent for National Geographic News and the Christian Science Monitor. His work has been funded by The Pulitzer Center for Crisis Reporting and the North American Congress on Latin America.

Reporting on the oil crisis in the Amazon, Kelly Hearn contributed an essay and photographs to our summer issue. “A Jungle Tiananmen” delves into the multilayered interests that underpin a brutal protest in Bagua, Peru, in which the native community faced off with paramilitary police over land reforms. Hearn is a correspondent for National Geographic News and the Christian Science Monitor. His work has been funded by The Pulitzer Center for Crisis Reporting and the North American Congress on Latin America.

1. What drew you to reporting in the Amazon?

I wanted to help draw attention to the fact that, as the world seeks politically cheap oil, companies are moving into the planet’s most biodiverse places. Few have reported on the oil boom that has been spreading across the western headwaters of the Amazon basin—and that is perhaps the largest development threat in the entire Amazonian region.

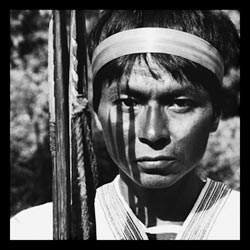

2. Your photographs for the article are all in black and white, with the subjects captured inside a small, square frame. How did you decide to shoot in this style?

I know very little if anything about photography and talking about it makes my head hurt. To me, good journalism is tapping into human passion and longing. So I guess you could say I try to go where the passion is. The way cameras are today, I turn everything on automatic and try for a second to become one with that passion, with that human intensity. There is no room for shyness. Sometimes everything works. A million times more it doesn’t. But I throw enough spaghetti at the wall, so to speak, and usually something sticks.

3. There is a moment in the piece in which you question your neutrality—“we were complicit in something. We were journalists, yes, but we had prior knowledge of an unlawful meeting.” Do such moments happen often during your reporting, and how do you usually handle them?

3. There is a moment in the piece in which you question your neutrality—“we were complicit in something. We were journalists, yes, but we had prior knowledge of an unlawful meeting.” Do such moments happen often during your reporting, and how do you usually handle them?

I’ve never had an experience like that before where I felt that the authorities might scoop me up as a kind of conspirator. I’ve certainly interviewed plenty of people who are considered criminals, but I can’t offhand think of any situations where something of that magnitude was being planned.

4. It has been a year since the protests and deaths in Bagua. Do you feel like public perception or understanding of this event has changed since then?

I am somewhat out of that loop because I’ve been working on a book here in the States for several months now. But I will say that the divisions between Peru’s indigenous people and the elite are quite rigid from what I’ve seen in many trips there. Bagua certainly shows that Amazonian societies aren’t going to take things sitting down as they might have in the past when they were less informed and less connected to international backers.

5. What projects are you planning for the future?

Someone needs to do thorough reporting on the revolutionary conservation initiative in Ecuador’s Yasuní National Park, known as Yasuní-ITT. There has not been a good account in the English language press. I am talking to editors about that possibility.