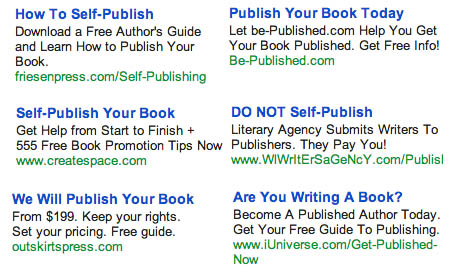

Help me out with a little experiment, ye avid consumers of the fine arts: open up your Gmail account (if you have one) and take a look at that one-line ad at the top of your inbox. Is it a self-publishing link? If not, refresh the browser. How about now? Still no?

If you’re anything like me, you’ll get a self-publishing advertisement within five reloads. That translates to a hell of a lot of ads! The evidence greets us every day: self-publishing is a booming business. And these companies—or at least Google—view us as part of the potential market.

Or do they? Clearly Google’s algorithms just aren’t up to snuff, right? Obviously they can’t distinguish between you—a connoisseur with literary taste—and your grandmother who occasionally sends you her latest masterpiece of rhymed verse about her cat, and who lost five thousand dollars last year when she happened upon an investment opportunity with a Nigerian prince.

Except we’re talking about Google here, which is the closest not-imaginary entity there is to God. Since Google ads only collect fees when a link is clicked, that means you can bet your ass that the advertisement is, indeed, intended for you. You—can you believe it?!?—who got that nice note that one time from an editorial assistant at the New Yorker, which when you’re drunk or downhearted enough you claim was a note from the editor him/herself (haha, just kidding: obviously himself). How insulting.

It’s easy to regard these companies as snake oil salesmen who—unlike literary and trade publishers, of course—have no interest in quality and are just out to make a buck by preying on ignorant or delusional self-proclaimed geniuses. But it’s way more complicated than that. Publishers, writers, and readers alike really need to sit down and take this trend seriously, rather than using the poetry.coms and AuthorHouses of the world as straw-men, scapegoats, piñatas, or other bludgeonable what-have-yous in the same tired and ineffectual arguments about how the Internet is ruining the publishing industry.

For the same reasons that web developers often look to porn sites (uh, well okay, there are other reasons web developers look at porn sites) because the porn industry pioneers some of the most successful web-development and marketing techniques, we should all take a good look at these companies—not to “lower ourselves to their level,” but because these companies indicate irreversible changes in publishing. And if publishers play their cards right, these changes could result in a renaissance of literature, rather than its oft-oracled destruction.

The Causes of the Publishing Apocalypse

The causes you’ve heard before go like this:

- Nobody reads anymore.

- Big publishing houses ate themselves alive by buying out the smaller publishers that were the lifeblood of literature, and then enslaving those imprints to the whims of the marketplace.

- Big Bad Amazon came along and destroyed the small bookstores that were vital to publishers’ distribution networks, and then double-screwed them by attempting to cut out the publishers as middlemen.

Point one is patently untrue. More people read than ever before, just not books per se, so we need to redefine or repackage “the book.” Points two and three aren’t wrong—they’re right in many respects—but they don’t constitute the full story. Besides, point three is essentially irrelevant: publishers aren’t victims of big-business capitalism, they simply haven’t adapted very well to technological change. They failed to present a more literary-minded alternative that could hold its own against Amazon, which is part of what allowed Amazon to take over.

Back in the day, it literally paid for a writer to get his or her book picked up by a big-name press. It still does, to some extent. But six-figure (or at least high five-figure) book deals aren’t nearly as common now, even with inflation. Furthermore, writers needed those publishers to successfully advertise and distribute their work. Not so, anymore. And indeed the Internet is to blame, though “blame” isn’t the right word.

First, desktop publishing software and digital printing have made it possible for anyone to start a press, while e-books have begun to make literal “presses” irrelevant. Suddenly big-name publishers can’t control the marketplace in the way they once could—there are so many new competitors!—so they can’t offer as many huge advances because their ability to force a book’s popularity has disappeared. (The music industry, as I’ve written about elsewhere, is a good corollary for this.) Publishers also can’t afford to pay for an author’s reading tour, in the way they once could, nor to do as much advertising and marketing as before: it just isn’t as likely to pay off. Publishing has become a riskier business, for all parties involved.

The Internet also makes advertising more cost-effective, democratizing the marketplace even further: no more need for expensive mass-mailings or print advertisements that often require an inside connection at a trade journal’s ad department. E-mail, Google Ads, Facebook Ads, etc. don’t discriminate between small and large publishers, and their costs are extremely low. So anyone now has the means to advertise effectively, using demographics data that far surpasses that of the major publishing houses in its exactitude and effectiveness. The amount of capital required, up front, to publish a book has taken a serious (and awesome) nosedive.

And then there’s the doozey: because of the Internet, distribution doesn’t matter as much anymore, either. Nobody needs to go to a bookstore to purchase a book; anyone can buy it directly from a publisher, online, or from a third-party site like Amazon. So those networks and contact lists that publishers once cherished and guarded have become increasingly irrelevant.

But let’s reiterate: Amazon is just the face of a change that was, and is, inevitable. While it might be cool to go back to an era where urgent communiqués were distributed by pneumatic tube, it’s not practical and it’s just not going to happen. By which I mean, we can’t erase the changes brought about by the Internet, either. Publishing houses might complain about Amazon because it’s the most visible and immediate actor in this change, but when they gripe and groan about hard times caused by the online marketplace, they’re essentially complaining that not enough people hand-write letters or own fax machines anymore. And that argument should be offensive to most small presses and journals, which have benefited immensely from the rise of online publishing and distribution.

Oops, Just Kidding: Not the Apocalypse

Fervent and educated scholars of the Mayan civilization be damned, the world will not end this December. Nor is literary publishing doomed; it’s just fine. In fact, it could be better than ever, if small and large publishers make a greater effort to scout tech-savvy editors and publicists, in the same way that some small presses and newer magazines already have.

Actually, literary publishing already is doing better than ever. As I mentioned in my last VQR post, the number of literary presses and magazines has exploded in recent years. In that previous context, I was playing the devil’s curmudgeonly advocate, but I’ll flip my rhetoric here to say that the publishing world is now full of nonprofit (or no-profit) presses who just want to put good work into the world. And that’s a great thing, despite my prior nay-saying.

Yeah, it’s true, writers don’t get paid like they used to. And yeah, they have to do a lot of marketing themselves, and finance their own book tours. Both of these developments are sad, and we should all support publishers who make it a goal to fund their writers as much as possible; I’m not suggesting otherwise.

But let’s take note, too: this profitlessness and dedication to quality publishing has had positive effects, not just negative ones. Amazon is a near-monopoly (not to mention, as Charlie Stross has argued, a near-“monopsony”), but an equal or almost-equal cause of the big-publishing-houses’ recent struggles has been these small, profitless presses who are reclaiming the space that the big houses absorbed and destroyed back in the mid-to-late nineties and early oughts. This wouldn’t have been possible without the same technological advances that led to the rise of Amazon—the two just can’t be separated.

We might scoff at the self-publishing companies I mentioned at the start of this post, but here’s the reality: many small presses resemble those companies in more ways than they’d like to admit. I don’t mean this as a criticism of those small presses; I just think we’d all benefit from a more honest understanding of our current moment in publishing.

When self-publishers ask for money up-front from an author, as a prerequisite for publication, they’re not doing anything so different from what most small, respected literary publishers already do. How many presses and magazines fund themselves through contest fees, for instance? If you don’t already know the answer, I’ll tell you: almost all of them. Is collecting smaller amounts of money from potential contributors (and then denying 99.5% of them publication) really so much more honorable than asking authors to pay for their production costs in full?

Consider, too, how many of those contest entrants have no chance whatsoever at winning. If you’ve ever screened entries for a book prize then you know just how large this number is. These individuals submit to many, many prizes, year after year, and they likely spend more money doing so than they would have spent by going through a self-publisher in the first place. Eventually, some of these individuals do self-publish, but only after they’ve been milked for cash by small literary presses for a few years.

As e-publishing begins to dominate the literary marketplace, it will become more and more difficult to distinguish between self-publishers and literary presses, in terms of their funding structures. Literary presses will find it harder to justify contest fees, because a book’s “production costs” will be close to nothing. If presses maintain those fees, there will be no denying that a significant portion of contest proceeds go to the editors’ salaries, unless a lion’s share of those production savings are flipped into contributor payments.

Of course, I don’t mean to gloss over some of the more obvious distinctions between self-publishing and small-press publishing. Self-publishers don’t screen submissions, whereas literary publishers do, and this is a crucial difference of philosophy that we should maintain, at all costs. But we should also acknowledge that the distinction can get mighty blurry.

Slightly more than a year ago, a press called BlazeVox found itself at the uncomfortable edge between self-publishing and small-press publishing. The press was “cash-poor,” and while they screened submissions in a way that self-publishing presses don’t—by definition—they also asked for money from accepted authors in the same way that self-publishing presses do, to finance the production of each book. The size of the press’s annual catalog was also suspiciously large for an emerging publisher, leading many to wonder if the press’s screening process might be so loose that BlazeVox effectively was a self-publisher.

When the news broke, it was a total scandal; the whole literary community was pissed. And the online brouhaha which followed was a clear illustration that the majority of writers still perceive a massive gulf—both in philosophy and in business practices—between self-publishers and small-press publishers. In philosophy, they may be right. But in business practices? Sorry, not so much.

BlazeVox’s intentions, I believe, were good. They were hard-up, is all. They had poor business skills (a trait most literary-minded people share, let’s be honest), and they attempted to grow the size of their catalog before they had the money or quality of submissions they needed to do so. But should BlazeVox have folded, then and there, when they didn’t have the money to print the following year’s titles? Is that what we want? Really? If you say “yes,” then think long and hard about a world where the only books that get published are those whose editors feel confident about recouping their production costs from sales. Because that’s essentially what you’re asking for. And most literature of significance doesn’t do so well when it’s first released: it takes years. Decades, even.

The Post-Apocalyptic Future of Literary Publishing

Okay, let’s wrap this up before I get totally off-topic. How does literary publishing rally in such a way that self-publishing presses and their Amazon-sponsored look-alikes don’t pose a threat to the visibility and success of Good Writing?

1. They make better use of the technology that supposedly killed literary publishing in the first place.

Google ads. Facebook ads. Mail-blast software. Easy online ordering. E-editions. They have to maintain active and engaged social networking profiles, too. They need to make themselves as visible as those self-publishers and Amazon imprints.

Small publishers already have the means to do all of this, and many of them are already doing it, though they could stand to do more. Even this past week, a very reputable literary publisher (whom I love… please don’t hate me, unnamed reputable literary publisher) wrote to the CLMP listserv asking whether email-blast marketing might be more effective than mass postal mailings. And I thought, seriously? You have to ask this question, in 2012?

2. There is still a contingent of presses and publishers who bristle at the idea of “branding,” “marketing,” and the lot. Stop it.

This is especially true of university presses, and English departments in general (though that’s another post). They (you) need to get over that. I mean, seriously: you’re a publisher, not a religion. This notion that literary publishers should be “above” basic business practices is honorable insofar that it’s an extension of a commitment to quality at all costs. But in every other way, the notion is absurd, and it turns a blind eye to the outdated marketing efforts that literary presses already perform, without thinking much about them. (i.e. press releases and postal mass-mailings.)

3. Just get your heads out of the book.

I mean this in two ways. Marketing has moved online, and books themselves are beginning to become electronic, so publishers need to stop thinking so much about paper and glue, which are expensive and often not worth the cost.

But I also mean, get your heads out of “The Book.” The rules of publishing have gone out the window in the past decade, and if you look to past publishers for answers to your financial and marketing woes, you’re going to fail. Look at other cultural producers instead. Music. Television. Film. Podcasts. Standup Comedy. Change the game. Because if you don’t, it will change without you. It already has.

Next Year’s Model

New models for publishing have already been born, and in a few years’ time, we may feel silly for our fears about the death of literary publishing. I invite you all to posit examples of these new models in the comments section of this post, but in closing I’ll leave you with three that I’ve recently stumbled upon myself, while doing marketing research for my own literary startup (ahem, yes, I know: shameless self-promotion):

Plympton is a publishing company that is trying to bring back the idea of serialized fiction, appealing both to the new-media idea of online-only content, and the old idea of the “serial novel” that strikes a chord with the more traditional-minded literary set. If the success of their Kickstarter campaign is any indication, they’re going to make a big splash that might redefine the medium.

Foxing Quarterly is a print-only journal that is using the conventions of social networking to gain traction. They show that, despite my tech-minded proclamations in this post, New Publishing (Can I coin that? Am I coining that?) doesn’t have to look so different than Old Publishing, in terms of its product.

Writers Bloq isn’t a press or publisher (though they could easily move that way, if they wanted). Rather, they are trying to create a social network for writers, and to overhaul or replace the (frankly antiquated) “agent”-system in fiction. They are doing, in a sense, what the Council of Literary Magazines and Presses should have done a long time ago: fostering and enabling a network of young writers who can serve as an audience, a test-market, an advertising team, and a contributor base simultaneously.

The future of small-press and literary publishing is a hell of a lot brighter than many would have us believe. We’ll get there, but to get there we need to let go of our antiquated notions about what it means to publish literature, and what separates us (or should separate us) from the self-publishers, the big evil publishing houses, and the bigger, eviler Amazons.

Answer: not a whole lot.

———

Sean Bishop (@SB_Bishop) teaches in the MFA program at the University of Wisconsin. He is the founding editor of Better: Culture & Lit and the former managing editor of Gulf Coast. His poems have appeared in AQR, Best New Poets, Boston Review, Harvard Review, Ploughshares, Poetry, Salt Hill, and elsewhere.

Sean Bishop (@SB_Bishop) teaches in the MFA program at the University of Wisconsin. He is the founding editor of Better: Culture & Lit and the former managing editor of Gulf Coast. His poems have appeared in AQR, Best New Poets, Boston Review, Harvard Review, Ploughshares, Poetry, Salt Hill, and elsewhere.