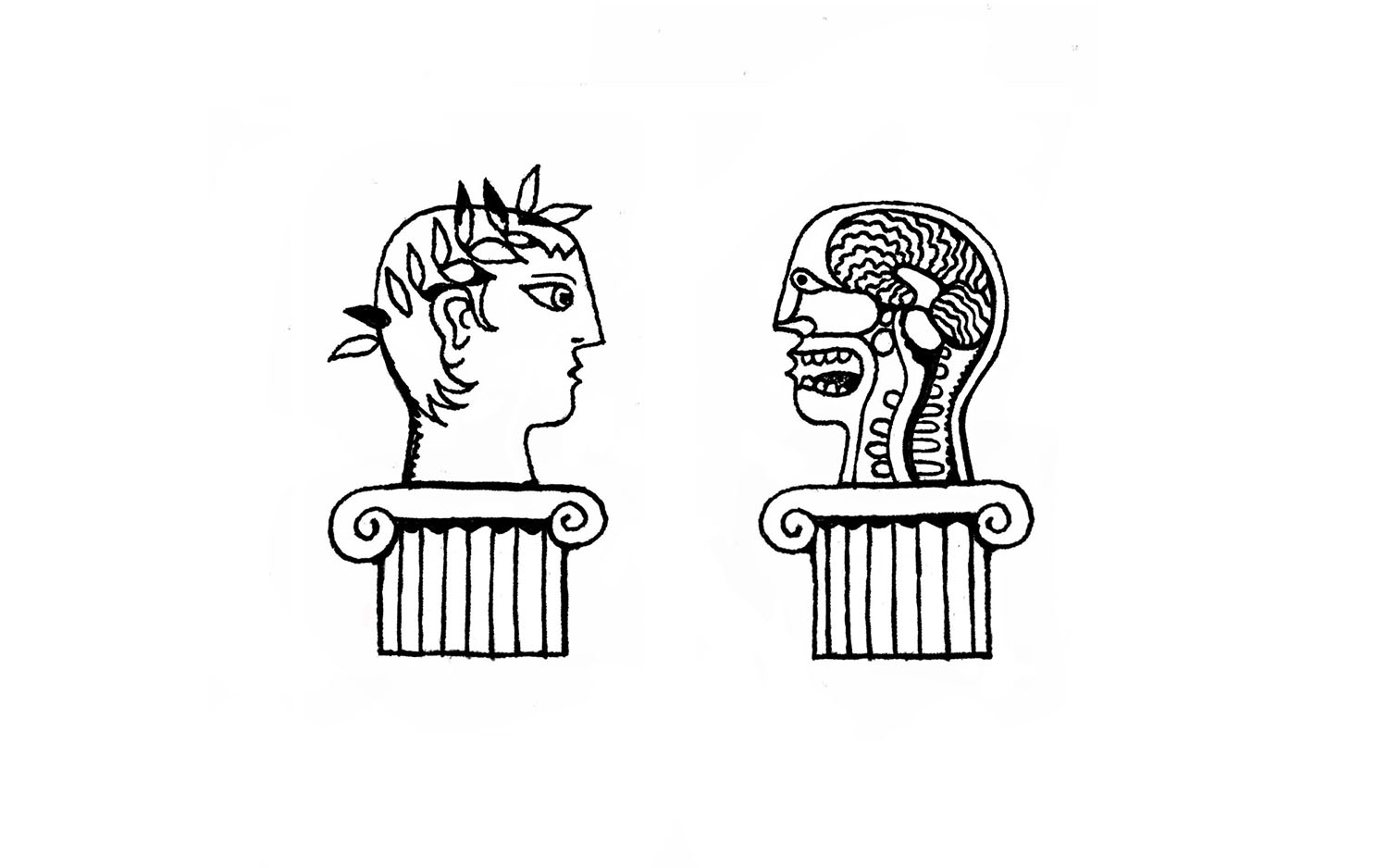

The American is “an idealist working on matter,” the philosopher George Santayana once noted. I shared his words recently with an audience of doctors, bioethicists, and psychologists during a grand-rounds lecture in New York about the relationship between literature and medicine. Physicians would do well to recognize themselves in Santayana’s formulation, I said. My talk was met with warm echoes about the importance of humanistic study. The residents seemed to appreciate the opportunity to think about how they might make meaning out of medicine (and were perhaps also thankful for an hour off from the wards). Practitioners and professors inquired about how to be better at cultivating a humanistic medical culture. Was it an issue of recruiting poetically minded students or reshaping the ones at hand? What books would be worth reading? What should humanities for doctors look like, and what kind of space should it occupy in medical-school curricula? The question that lingered with me most, however, came from the chair of the department, who asked what I often ask myself in private: Is there something inherent to the practice of medicine that makes integrating the humanities so difficult, if not impossible? Why, in other words, is it so hard to reconcile the matter of our idealism with the work of our practice?

It was a question that distilled my own anxieties about the precariousness of the humanities in medicine, the kind of question that haunts anyone who’s been in the medical profession long enough to be wary of easy bargains. The skepticism behind the chair’s question mirrors that of the philosopher Richard Rorty when he asked, albeit in a broader context, whether there was a place for sublimity in society. For Rorty, the answer was no. Perhaps wisely, the great pragmatist suggested that “we have to separate individual and social reassurance,” that we have to make sublimity “a private, optional matter.” Society, in Rorty’s view, “should not aim at the creation of a new breed of human being, or at anything less banal than evening out people’s chances of getting a little pleasure out of their lives.” His advice for citizens with a desire for transcendence? “[They’ll] have to pursue it on their own time.” Rorty had in mind here collective political attempts to achieve something metaphysically grand. He was skeptical of social institutions offering individuals access to the sublime (as well as of individuals seeking transcendence via group membership). Given that medical schools constitute their own kind of micro-society, explicitly making claims to produce virtuous doctors, it’s worthwhile to transpose Rorty’s contention upon the project of medical education and examine the uses and abuses of literature within it.

I imagine Rorty sitting in the back row of the lecture hall, listening to me rattle on about humanistic ideals in medicine, scratching his head and genially asking: You sure you want to do that? Rorty, I think, would say that the kind of correspondence I seek—between the stubborn day-to-day realities of medical practice and the transcendent sublimity of literature—is unachievable. The more you try, the more you’ll fail. And maybe he is right that we’d spare ourselves a lot of pain if we quit the posturing and just accept this reality. Instead of striving for the astral sublime (an unlikely privilege in all but a few trades), perhaps we should stick closer to Earth, squeezing out some everyday pleasure where we can. It’s a bearishly honest position to grapple with, one that cannot easily be sidestepped. Still, we can try.

The simplest response to Rorty might be to point out that pain, generally unavoidable, is especially pervasive for physicians. To be a doctor is to be a witness to what can happen to a body. And a lot can happen. Pain is so intrinsic to medicine that medical education may rightly be understood as an accumulation of wounds. Sublimity, then, is not merely optional for the healer, but necessary for her survival. How else are doctors to return again and again from encounters with physical decay, debility, and death—or from the subtler, deeper injury of time? The pursuit of the sublime is for the physician a search for a language that expresses the nature of this suffering. And in casting for this vernacular, the physician shares a common purpose (though not method) with Rorty himself: cultivating “the imaginative ability to see strange people as fellow sufferers.”

But is what passes as the medical humanities today capable of helping us create such a vocabulary? Literature, philosophy, theology, anthropology, and history are often paraded as an antidote to what ails doctors. One might even think the medical humanities are ascendant, given the recent focus on new initiatives—by the Association of American Medical Colleges, educational administrators, and hospital executives—to cultivate empathy, stanch burnout, and model “professionalism.” Curricular and workplace innovations rise up and keep rising up. By closely reading a poem, writing an essay, or critiquing a work of art, it’s possible to create more compassionate clinicians, fight back against the depersonalizing tide of medical education, bolster a sense of purpose, boost resiliency, and expand the agency of the individual behind the license—all while blithely increasing the efficiency of clinical practice. Or so the argument goes in white papers and journal articles that seek to show how useful the humanities can be as doctors go about doctoring. What was once a fringe movement to have the sciences dialog with the humanities has seemingly become commonplace—endemic even. But if such ideas have been co-opted into mainstream thinking, their metamorphic potential is tamed.

The pragmatic uses of this domestication are undeniable: Doctors are burned out, communication with patients is often stilted at best, medical training can drain the compassion out of a young intern. Physicians are buckling under the impossible demands of clinical care, and something needs to be done to help relieve this strain. So, they tell us: Read some fiction to improve your ability to relate. Try yogic meditation; let loose that toxic stress. Study philosophy and make better management decisions. If all else fails, come to “Wellness Wednesday.” This practical approach is understandable. Ultimately, though, it obscures the essential truth that the medical humanities aim to uncover and help us live with: that despite abounding biomedical prowess, doctors and patients alike inhabit a world defined by the limits of their mortality. It’s the kind of truth that resists being “operationalized.” The kind of truth worthy of grappling with Rorty’s challenge.

There’s nothing wrong with being a well-adjusted, empathic, and productive team player, of course, but rectitude should not be mistaken for vision. To enlist the humanities as part of a wellness checklist is to reduce their value to yet another self-care routine or feeble life hack that doesn’t transform one’s reality so much as make it more tolerable. This is the opposite of what Kafka had in mind when he wrote: “I think we ought to read only the kind of books that wound or stab us. If the book we’re reading doesn’t wake us up with a blow to the head, what are we reading it for?” The same question should be asked of the medical humanities. If our study doesn’t affect us deeply, how can it possibly change us? Rather than opening ourselves up to the kind of wound Kafka describes, however, we in medicine endeavor to disentangle ourselves from vulnerability and death. And perhaps this makes sense in a profession that regularly tackles death as a material fact, not just an existential provocation. But assimilating the humanities into the culture of wellness and professionalism is an illusory solution, an empty shortcut that facilitates the individual’s participation in flawed institutions: It takes the edge off moral injury without any meaningful disruption to the underlying structures that perpetuate it.

Unlike professional wellness culture, humanistic study—approached as spiritual discipline—can be a balm to the soul and giver of durable self-knowledge. But what would this self-knowledge look like in actual clinical practice? What would the hazards be? Do you want your heart surgeon breaking down in the middle of a bypass because she has an existential moment upon seeing your beating organ, like Hamlet holding poor Yorick’s skull? Of course not, but the extreme of the callous compartmentalizer isn’t much of an ideal either. The challenge is to be a conduit for real emotion without becoming Hamlet in scrubs.

The medical humanities might help us achieve such counterpoise, but only if we recognize that their primary value isn’t derived from how they make us more professional or better communicators or more culturally sensitive. Rather, the fuller aim of literary study is to put us in closer contact with the ever-elusive Real—that truth which exceeds language. Insisting on the presence of this untidy surplus might not loosen the grip of institutional medicine completely or all at once. But there is dignity (and maybe even a little joy) in dissenting against the tide of hyper-professionalization in medicine, and it might eventually help doctors avoid the trap of toiling away as specialists with no viable home for their spirits.

Many physicians sympathize with some version of these sentiments, but more than a few also tell medical humanists (tacitly or aloud or through plain neglect) to “get real.” What about the hard work, they ask, of mastering vast quantities of scientific knowledge? What about the interminable duty hours that pack weeks’ worth of work into days? Will a poem ever treat a cancer or bring a person back to life? How can this stuff possibly help pay off the massive student-loan debt doctors take on or buy a house or contribute to a 401k? And besides, how can you even think of asking a sleep-deprived trainee who didn’t sign up for any of this to ponder Aristotle or Hortense Spillers? There must be rules against that sort of thing, no?

These are the kinds of question that proponents of the humanities in medicine are often asked the moment they make real demands on institutions or aim to be something more than widgets advancing the cause of professionalism or fighting burnout. Perhaps it’s fair—even necessary—to admit that the path to mastery of a field like medicine is grueling. One must traverse the dense terrain of anatomy, physiology, and pathology to arrive at any expertise in clinical practice. Along the way there are seemingly endless taxonomical distinctions, biochemical pathways, pharmacotherapeutics, suture techniques, and treatment algorithms ready to trip you up if they aren’t properly memorized. With so much information to absorb, and with so little time to do it, you must face the possibility that you can’t have it all. A fish, after all, cannot be a bird.

And when it comes to the question of actual healing, it’s true that a poem in and of itself will never cure an infection or excise a tumor or bring a heart out of asystole. A poem can, in fact, seem pretty useless when it comes to getting out of a medical predicament. But take a closer look and you’ll see an emergency behind the emergency: the soul-struggle of the doctor dedicated to her patients. The power of the poem lies in its ability to revive this physician, bringing her back not from the dead, but rather from death-in-life. As William Carlos Williams, who snatched time to versify between patient visits, wrote: “It is difficult / to get the news from poems / yet men die miserably every day / for lack / of what is found there.”

Educational institutions are reinforced by molding students and faculty in their likeness. So it’s worth a student doctor’s time to ask, amid the bustle of professionalization, Who is going to produce my self? It’s possible that we’re already too far down the road, in some corners of academia, to recover from the conflation of self with monetizable professional identity, but I believe there are still learners (and teachers) who’re looking to education as an opportunity for spiritual self-fashioning.

The cost of forfeiting this opportunity is articulated perfectly by another writer who doesn’t exactly feature regularly in medical-school syllabi, but with whom just about any poet is already familiar. Though he never dissected a cadaver, the existentialist philosopher Søren Kierkegaard was deeply concerned with the anatomy of the self. In particular, he was devoted to fighting against the atrophy of the soul—a word that doesn’t appear at all in the AAMC’s forty-four-page 2020 report, “The Fundamental Role of Arts and Humanities in Medical Education.”

Such atrophy, in Kierkegaard’s view, is an ever-present risk for anyone trying to engage meaningfully with the world. Public life constantly has us becoming something—doctor, teacher, parent, mate, worker, citizen, what have you. To become is, on the one hand, to participate in a sphere of vitalizing possibilities. But becoming also exposes the self to a world, as Kierkegaard saw it, overfull with the clatter of society, in the grip of materialism and technology, and subject to the seemingly inescapable pull of capitalism. In other words: the carnival of bourgeois striving, insidious structural violence, and relationships between achingly empty interlocutors mediated by numbingly luminous screens—all of which medicine has its share of. How does the self navigate this gyre without getting lost in it?

The study of humanities is characterized not by its answer to this question, but rather by its commitment to posing it aloud—to saving us from losing ourselves in the silence of the unasked. The medical humanist recognizes truth in Kierkegaard’s observation that “[t]he greatest hazard of all, losing the self, can occur very quietly in the world, as if it were nothing at all.” One of the gravest mistakes we in medical education can make is to assume that articulating questions about how to live is optional for our students, that at the end of the toilsome path of medical education—with its built-in benchmarks of board exams, graduations, overnight calls, and the structured chaos of residency—the gift of one’s identity will lie waiting as part of the reward for all that hard work, if not fully formed at least partially ready to inhabit.

In fact, silence on the part of individuals and institutions only feeds the illusion that the work of self-fashioning is actually happening, that a coherent narrative of the self is being written by someone, somewhere, while technical mastery grinds on. It’s easy to see why silence is tempting: There’s already so much required of the student doctor, the thought of taking on more work can seem absurd to learners and institutions alike. But as things exist, what’s needed for going along in medicine is not necessarily commensurate with fostering an inner life. It can sometimes feel as if Kierkegaard was right, that the losing of the self is precisely what’s called for to make a great success in the world. The humanities, however, keep us from becoming numb to our despair by helping us remember to chafe against constrictive institutional vocabularies. They prevent one from becoming what Kierkegaard described with scathing irony as an individual “so far from being regarded as a person in despair that he is just what a human being is supposed to be.”

Still, there are risks that come with refusing to be what a doctor “is supposed to be.” First-year med students sometimes tell me that they find it tough to engage in literary or philosophical discussion in my medical humanities seminar and then return to studying for six to ten hours a day. These students value the questions we ask in class, but fear that giving too much of themselves over to humanistic inquiry will leave them intellectually unquiet and unable (or unwilling) to replace the blinkers needed to accomplish the feats of memorization it takes to pass exams. Who, they wonder, will sit at a desk and hammer through stacks of flashcards or watch a recorded lecture video at two-times speed or keep track of the array of labs and images that direct patient care? What’s more, students judge that a pass/fail humanities seminar can’t matter nearly as much as the numerically graded hard-science courses that report out percentiles and means and standard deviations. So why risk so much for something that isn’t “essential”?

For the medical humanities to be seen as essential, they cannot float in isolation or be ignored by the hard clinical side of a medical curriculum once students leave the seminar room. The traditional approach has been to ask how the humanities might help solve problems like burnout without necessarily changing the way clinical medicine is practiced. In other words: problems with roots in the clinic and on the wards get sent to the classroom for their solutions. However, the meaning and impact of what’s discussed in a lecture hall depends on how we practice beyond its walls. Instead of asking the humanities alone to be responsive to clinical realities, we need to start calling on clinical medicine to substantively incorporate the hard-earned lessons of humanistic study. This is a heavy lift. Economic pressures and practical exigencies flatly resist the kinds of change that could make a difference.

Nevertheless, there’s good reason to push back. In many cases, the humanities seminar a medical student takes is far more likely to remain relevant to him when he’s a practicing doctor than the operations of an obscure biochemical pathway. Such classes should get their proper due by taking up a bigger footprint. Lop off outdated parts of the curriculum to make room for what matters most. Put more curricular power in the hands of the literary scholars, the anthropologists, the poets, the historians, the philosophers—or at least the kind who’ve devoted themselves to learning how literature in all its forms might help us to live. And why not recruit more students with undergraduate humanities degrees or make such training a prerequisite alongside organic chemistry? These are hard decisions and few will be willing to cede curricular ground. But what good thing ever came easy? Proponents of the humanities must stop having these conversations as though we’re visitors in our own home, sideshows to be tolerated rather than indispensable pillars of a student’s formation. Not to do so is to fail our trainees and their future patients.

The best—and most fulfilled—doctors I’ve met have found a way to let themselves be remade by the hard craft of medicine without being entirely broken in by it. They know, like Emerson before them, that “the most abstract truth is the most practical” and are willing to fight for its preservation. How well we do the same will help decide whether the humanities in medicine get co-opted as vehicles for lite moral entertainment and derivative self-expression or exist as real tools for living.

The thought of denying such powerful tools to medical students, the majority of whom come from STEM backgrounds and have not rigorously studied the humanities, unsettles me. I’m lucky enough to be at a medical school that tries to keep the door to the humanities open through a curriculum taught by multidisciplinary scholars and physicians. In my seminar, I start by discussing Rorty’s concept of the “final vocabulary,” which he describes as the unique set of words that every human being uses to “justify their actions, their beliefs, and their lives.” A healthy final vocabulary, paradoxically, is not final at all, but evolves as we use it—absorbing new words and redefining old ones to give us the tools we need to live life in concordance with our self-professed ideals.

In this spirt, I ask my students to list some words they think might constitute a physician’s final vocabulary. Compassion. Respect. Truthfulness. Duty. Humility. Work ethic. These are just some of the regulars. Increasingly frequent: Justice. Then we test our definitions of these words against one another. Disagreements flare up—as they should—about what these terms mean, who they include and exclude, the gap between our vocabularies and our actions. Remarkably, though, students from considerably different backgrounds usually manage to create a loosely shared constellation of words to live by. It’s a makeshift vocabulary, to be sure, with gaps that each of my students will discover and fill through the course of their lives as doctors. But what astonishes me just a little every time is that the exercise works at all.

What’s the force that stitches these words together? Rorty would suggest that these students have simply been socialized to hold these words dear and, moreover, that their values are contingent upon this shared socialization, not grounded in a reality beyond it. Maybe this is true. But I wonder if another possibility is also at play here, one that could free us from the limits of contingency while also leaving us open to the self-generative power of Rorty’s fluid vocabularies. Namely: that the reality undergirding my students’ shared language is an awareness of the common experience of human suffering. Although no two people, including doctor and patient, suffer the same way, or to the same degree, the fact that we all suffer is a democratizing truth. Might it be that the pain of being and dying can serve as the substrate upon which we can build a shared vocabulary—a vocabulary that can actually bridge the individual sublime with social existence?

It’s a question no one can answer alone. But for me it holds the promise of a viable path forward. A path on which we can not only construct a life as literature—nimbly writing and rewriting the vocabularies of the self—but also remember our shared suffering when the world inevitably tears our first drafts apart.