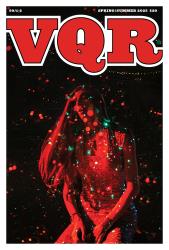

In 2019, photographer Michael O. Snyder approached VQR with a project that, even in its title, promised to be as dazzling as it was provocative. “The Queens of Queen City” is his immersive photodocumentary, nearly a decade in the making, of the drag community of Cumberland, Maryland, in northern Appalachia. Just a few images into it, I was struck by what its premise asked of me, because, by engaging with it and being honest about the surprise that drew me in, I had to confront a reflexive bias: How can drag culture thrive in such a deeply conservative part of the country? This paradox gives the project its magnetic pull, but the dissonance is illusory, and purposefully so, as it mirrors Snyder’s own edification about the region where he grew up. Of course queer communities have claimed space in Appalachia. That’s because it is far more complex and nuanced than we tend to give it credit for being.

In 2019, photographer Michael O. Snyder approached VQR with a project that, even in its title, promised to be as dazzling as it was provocative. “The Queens of Queen City” is his immersive photodocumentary, nearly a decade in the making, of the drag community of Cumberland, Maryland, in northern Appalachia. Just a few images into it, I was struck by what its premise asked of me, because, by engaging with it and being honest about the surprise that drew me in, I had to confront a reflexive bias: How can drag culture thrive in such a deeply conservative part of the country? This paradox gives the project its magnetic pull, but the dissonance is illusory, and purposefully so, as it mirrors Snyder’s own edification about the region where he grew up. Of course queer communities have claimed space in Appalachia. That’s because it is far more complex and nuanced than we tend to give it credit for being.

Snyder was raised just over the mountain from Cumberland, in the tiny mining community of Borden Shaft (population three hundred). In a town that size in a largely conservative part of the state, it’s reasonable that a straight man wouldn’t know drag existed in Cumberland—never mind that an LGBTQ+ community held strong there—until 2011, when he and his sister, home for the holidays, went to a drag pageant they saw listed in the local paper.

“To be honest, it was a mess,” Snyder recalls. “The fog machine wasn’t working; the music was off. It was just a total disaster. But the people doing it were so incredibly committed. They were just pouring themselves into the performance. That was half of it, just seeing how fantastic they were in their commitment. The other half was that the audience was much more diverse a crowd than I ever would’ve expected. So the stereotypes I had about the way this community exists and the way they think about queer identities were much more complicated than I’d considered, which challenged me to think more deeply about who supports this and who this is for.”

Over the next several years, Snyder got to know members of the drag troupe. He went to shows, learned about drag’s legacy in Cumberland, and through this lens began to understand how the region’s libertarianism, conservatism, liberalism, populist and proletarian movements, faith and fidelity to community all fit together. He took his first portraits in 2016—of queens Iva Phetish and Mona Lott—which became the foundation for a visual narrative that layers the elation of performance with the fears and strife and tenderness, even the mundane routines, of the performers’ day-to-day lives in Cumberland.

Rae Garringer, who runs the multimedia oral-history project Country Queers, teamed up with Snyder in 2020 to write the essay that accompanies these images. For Garringer, the assignment was a natural extension of the work they’ve done since 2013 documenting rural LGBTQ+ experiences and an opportunity to counter narrow preconceptions of the region.

“There’s this idea in national queer spaces that rural places are unsafe and dangerous,” Garringer says. “But that idea further erases queer histories here. So the narrative that rural spaces are monolithically conservative, Christian, and homophobic needs to be busted open a little bit. Because there’s also the reality that, among all the interviews I’ve done for Country Queers, most of those people have never had a problem in their communities. Their neighbors know who they are. The larger idea of queerness may be scary, but people can also be very accepting of their own in small towns.”

Not long after Garringer came on board, COVID-19 all but shut down the project’s access to Cumberland until 2022. In that time, queens emerged onto the scene while others left it; they were tested in ways both familiar and unexpected, though none of us anticipated the ways in which the recent blitz of legislation targeting drag culture and trans youth would frame their narrative.

That fight points to a difficult truth: Amid all its aspirational qualities, the American experiment will always include a certain amount of fear—in this case, about sexuality and gender—that resists the push for freedom of expression and the right to exist on one’s own terms. And yet, this fight isn’t the whole story. The menace of violence and silencing that has marked the LGBTQ+ experience—whether imposed by others or self-imposed as a matter of survival—is undeniable. But as Garringer and Snyder both point out, to define the rural LGBTQ+ experience according to this tension alone is to miss the nuances that make its story so compelling.

It stands to reason, then, that these relationships are more multifaceted than we presume; that where people stand in the national conversation about LGBTQ+ rights can differ from how they might treat each other as neighbors; that rural conservative voters might cast their ballots one way, but still attend a local drag-show fundraiser for LGBTQ+ people who don’t have health care. The fact that drag troupes—and by extension, queer and trans communities—are so publicly claiming spaces in rural America forces us to take a closer look at the underlying biases that make this surprising in the first place. Certainly there’s been a push from within conservative counties to suppress the queer experience. But, as Garringer will tell you, the visibility that drag culture represents has been intensifying in places such as Cumberland for years.

The entangled truths at the heart of this project—to which we’ve dedicated the most pages of any photo portfolio, and around which we’ve built this special double issue—are a reminder that the work of telling the stories of different Americas requires vigilance and careful attention, especially in light of dominant storylines that tend to be redundant and reductive.

As familiar as Garringer is with the landscape of rural LGBTQ+ consciousness generally, the ability to dive deep into a single community and document the influence of its queer and trans elders had a surprisingly powerful effect, since it underscores how achingly absent the voices of past generations are from that broader consciousness.

“The fact that in the ninety interviews I’ve done for Country Queers, maybe fifteen have been with people over the age of sixty is very much the result of how we’ve been robbed of our rural queer elders. I never quite realized until this year how much grief I have about that piece of it. I wish I’d started interviewing elders from the beginning. In interviews I always ask ‘Did you grow up seeing queer people who were older than you in your community?’ And people do have glimpses, but usually they didn’t really know them, and they don’t know their stories in the way that some of the queens in this story do. It reminds me of one of the first interviews I ever did, with a friend from southwest Virginia, who said that when you grow up Appalachian, a big part of the culture is that you get all these stories about your family and your people. But when you grow up queer, you get none of that, so you feel like maybe you don’t belong, in a way.”

The lessons Snyder takes from his own experiences in Cumberland speak to this need for legacy, and to the undercurrent of healing that can be found in these performances, one that isn’t so different from what people seek from more conventional traditions. “If I were to talk to someone who wasn’t convinced that this was a good thing for society, who thought drag was unhealthy, the way I’d answer that is that the number one value drag performers bring to a community is that they are doing a form of shadow work. In any community, queer identities are there. That’s just a fact. I think what drag does, even though it’s just kind of the leading edge—you know, it can be messy and ugly sometimes if it’s not done for the best reasons, and of course not all drag performers are saints—but it creates a space for somebody who, until then, maybe didn’t think it was possible to express who they are. It opens that door of possibility they can step through and ask more questions. That work is really hero’s work. If there are people in the community who feel less alone and more embraced and more secure because of going to one of those shows, that’s huge. That work, that softening, ultimately has a benefit for all of us.”