Of all the arts, film and jazz are arguably our nation’s most original contributions to global culture. Though music will have to wait its turn, we have decided to focus on the United States’ most pervasive export, Hollywood movies.

Of all the arts, film and jazz are arguably our nation’s most original contributions to global culture. Though music will have to wait its turn, we have decided to focus on the United States’ most pervasive export, Hollywood movies.

In this issue of VQR, we’ve gathered unknown, untold, and forgotten stories behind Oscar-winning classics that still influence the way that people view the world today. As much as we appreciate (and occasionally envy) the glamour of Vanity Fair’s Hollywood issue and the breaking-news access of the Hollywood Reporter, we prefer a historical lens through which to address the industry and its homegrown mythology.

From the eclipsed icons of silent film to the stars of Bollywood, from the set of a breakout, made-for-tv movie to how the publicity game is played, from Walt Disney’s Snow White to Akira Kurosawa’s Rashomon, we have tried to provide an insightful glimpse at how screenwriters, illustrators, actors, stunt persons, producers, directors, and crews bring words and images to life on the silver screen.

As a staff of writers, we have our own biases—which may account for the attention paid to screenwriters, including Horton Foote, Paul Dehn, and Budd Schulberg, and how they braved working in the so-called Dream Factory.

One could hardly script a greater challenge than faced the nascent screenwriter and director George Lucas when he undertook the adventure of filming Star Wars in Tunisia in 1976. In the course of transforming science-fiction literature and the film industry itself, Lucas turned a little-known African country into a film-location mecca. VQR contributing editor Jesse Dukes takes our readers to the wind-worn, sunbaked Star Wars structures that still attract a modest but steady stream of tourists decades after the historic film wrapped. Dukes frames this legacy against the backdrop of the Arab Spring, while exploring Tunisia’s indigenous film industry, post-revolution.

With the purchase of Lucasfilm by the Walt Disney Company for $4.05 billion in stock and cash in 2012, one can expect many more feature-length episodes from this legendary franchise. The question is: Will the studio maintain the artistry of the original film, or merely cash in on the brand?

Regarding the tension between the creation of art and the encumbrances of the marketplace, the perspective of the late Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright Horton Foote is just as pertinent today as when he offered it forty years ago. As the screenwriter for To Kill a Mockingbird and Tender Mercies, Foote followed the adage of Henry James: A writer must not report, but render. We are honored to run an extensive interview with Foote, which is being published for the first time here and in a new book, The Voice of an American Playwright. When properly constructed, a good interview is a memoir by another name.

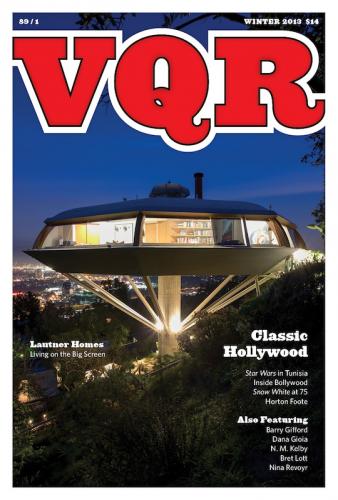

In addition to behind-the-scenes photo essays on Bollywood and stunt doubles, this issue presents two California dreamers—modernist architect John Lautner and visionary artist Leonard Knight—through exquisite photographs of their iconoclastic creations.

In his essay on Lautner’s L.A. homes, Adam Baer distills the essence of the architect’s hillside residences featured in movies such as Diamonds Are Forever, Body Double, and The Big Lebowski. Frank Lloyd Wright once declared Lautner the second-best architect in the world—after himself, of course. Thanks to photographers Elizabeth Daniels and Ken Hively, one understands why Wright held him in such high esteem.

A generation after Lautner designed these homes of secular beauty from concrete and redwood, Leonard Knight used straw and adobe clay to shape a sacred space—Salvation Mountain—in the California desert. With his camera, Aaron Huey offers a loving appreciation of one man’s faith.

Hollywood and poetry? Yes, actually. Barry Gifford, screenwriter of a Palme d’Or-winning film at the Cannes Film Festival, delivers a powerful poem about a screen femme fatale. Dana Gioia scripts noir verse in the tradition of Body Double, and William Baer explores lost love through tracking-shot sonnets. Four other poets work their magic outside of this theme to equal effect.

In a significant artistic departure for him, novelist Bret Lott tries his hand for the first time as a biographer, introducing us to Frank Price, former chairman of Columbia Pictures, in impressionistic scenes from Price’s Depression-era boyhood, his rise as a television writer, and big wins at the Academy Awards. Echoing Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath with the Price family’s Joad-like journey to California, Lott places the reader squarely in the bed of the crowded Model T truck next to young Frankie and his short-tailed dog Mickey.

The theme of a literal journey persists in each of our fiction selections, from Russian author Vsevolod Benigsen (translated into English by Reed Johnson), short-story writer Manuel Gonzales, and novelist N. M. Kelby.

In terms of VQR as an organization, we have launched a search for a new editor. We expect that the selected candidate will have strong ideas for how we can improve our efforts, enrich the reading experience, and sharpen our focus. As we eagerly await this transition, we ask our readers to share what you love, like, loathe, or just linger over in our pages. It is your magazine, too.

Regardless of who is selected as VQR Editor, we can make a few important commitments: Literature is here to stay. You will continue to find fiction and poetry and memoir in our pages. We are committed to long-form nonfiction, whether investigative journalism or the personal essay. We stand by our engagement in recent years with photojournalism. But in other ways, we are in the midst of crucial conversations about how to ensure our continued leadership in the community of ideas. What is the best form for VQR in the twenty-first century? Are we a literary quarterly, a cultural magazine, or both? Do we value words first and foremost, or see photography and multimedia as their equals? In dialogue with our readers, we need to tackle these questions.

Our website now attracts more than 300,000 unique annual viewers from more than 206 countries and territories. To put these figures in perspective: VQR has more online readers in India than the print magazine has ever had in subscribers, worldwide, at any point in our eighty-nine-year history. By late spring, we will have a new, content-rich website that is more interactive and mobile-friendly with exclusive online-only content. Also, we have launched a digital edition of our magazine in the universal PDF format for use on Kindle, iPad, NOOK, and other tablets. We will continue refining our approach and will offer editions native to major platforms. Our commitment to multimedia content and digital subscriptions is not about print versus digital, eyeballs versus paywalls. We love bound pages, love the interplay of ink and images, but we are media agnostic. It’s not a choice of either/or, but of both/and. We have been and remain storytellers. We will deliver our stories in the formats that best match our audience members’ reading preferences.

Where our readers are, we will be, too.