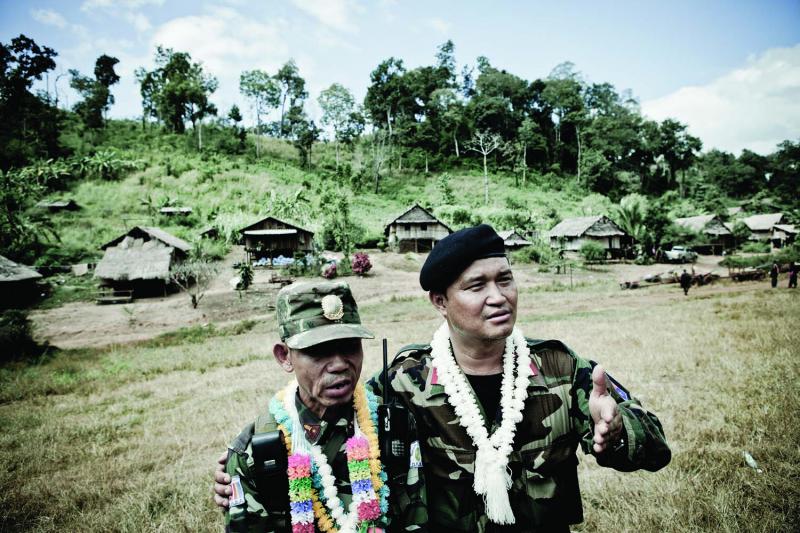

The steady roar of distant mortar fire didn’t seem to bother Lieutenant Colonel Nerdah Mya. The forty-one-year-old commander of the Karen National Liberation Army’s 6th Brigade had changed out of his dress uniform into a black T-shirt and beret and was now relaxing by candlelight under the stars in the tiny village of Krep Po Ta, surrounded by legless war veterans and childlike soldiers. That hot sunny day, the son of the late Karen supreme commander Bo Mya had just concluded a public peace-making with a local unit of the government-backed Democratic Karen Buddhist Army, but at night when the media was gone, grim reality returned. “There are about one hundred government soldiers making their way towards us,” Nerdah said. “I will send my men to attack them and mine the way.”

As Nerdah Mya’s attention turned to the dinner of rice and tinned sardines, it seemed like just another disappointment in the sixty-year-old war between the Burmese government and the Christian-majority Karen insurgents. Ever since Burma broke free of British rule in 1948, successive governments have largely controlled the country’s central river delta. Tribal and ethnic groups, including the Karen, have fought for varying degrees of autonomy in mountainous areas along the country’s long border with India, Bangladesh, China, Laos, and Thailand. From the vantage point of the insurgents or foreign groups that try to help them, the on-again/off-again fighting has left Burma divided: black zones, contested tracts that are largely off-limits to foreigners; brown zones, largely controlled by the Burmese; and white zones, where people can move freely, though public dissent against the government is less than encouraged.

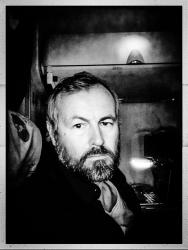

Photographer Jason Florio and I wanted to visit a black zone. Karen territory— Kawthoolei as the Karen call it—lies a mere hundred miles east of the capital of Yangon, a landscape of steep limestone cliffs, lush valleys, thick jungle, and the swift Salween River. It was there we found Nerdah Mya, readying his Karen rebels for what appeared to be their last stand in a brutal war of attrition with the Burmese army and its extended government, the Tatmadaw: it’s an army which is estimated at 300,000–400,000 men. Comparably fuzzy estimates place the Karen army at 8,000.

It was early November 2010, election time in Burma. It was the first in two decades, and an election most people knew the ruling Generals would rig in their favor. As if a symbol of their confidence, they released the pro-democracy opposition leader, Aung San Suu Kyi, from house arrest on November 13, six days after the vote. The world beyond applauded, but it did little to dissuade the rebel leadership from its ongoing sense of mission. The tribal Karen National Union have been fighting since their first post-colonial battle on January 31, 1949—so long that younger fighters suspect the aging Karen leadership had turned war into an ongoing business.

The Burmese Generals, who have ruled the country since a coup in 1962, have just built three dozen new military bases inside Karen territory, carving new roads to carry troops into the steep jungle terrain. They have purchased fifty Russian Hind attack helicopters and twelve transports in preparation for what some feared would be a final campaign of infiltration, assassination, assault, and assimilation.

I wanted to see what the rebels were planning on the eve of the April 2012 elections, but getting inside rebel territory requires complex coordination with the locals, who maintain a love-hate relationship with the Thai government. The huge influx of Burmese refugees forces the Thai government to support rebel groups covertly while publicly denying support so as not to offend Burmese business agreements. We drove hours from Mae Sariang along winding mountain lumber roads to reach the Salween River and then, for being so visibly foreign and illicit, were hidden under a dirty tarp and ferried across to a Karen refugee camp over the border. What can’t be seen can be denied.

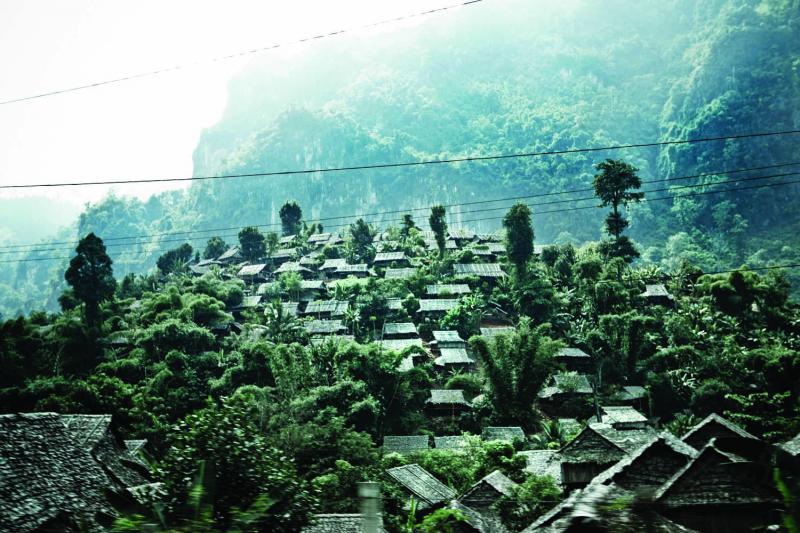

The camps for Karen and other Burmese refugees on both sides are surprisingly clean, orderly, with self-appointed management, security, and logistics. People smiled and waved when we arrived at dusk; food, blankets, and mosquito nets appeared without prompting. We spent five days waiting for the legendary Thai Boon, the head of Ranger 49, a group named for the year when the Karen War began. He was the man who could send us inside to meet the rebel generals, but he had never answered our calls on the satellite phone. Then one night, as we were out for a can of warm Chang beer at Nanji’s store, a favorite local hangout, there he was, seated on the store’s split-bamboo floor.

Thai Boon had been called to the camp to meet with the heads of the 3rd, 5th, and 6th brigades to plan an offensive. While the villagers watched a bad Dennis Rodman movie, Boon rolled out a map on the floor. He slid cheroots onto the map to mark the spots of rebel camps. He chuckled with glee. “Oooh. It’s another planet! The rest of the world goes forward in time; we go back 250 years. You will see!”

Before sunrise the next morning, we were on. We arrived at General Bo Jo’s commando training camp before dawn and as we hiked up from the river, the first noise we heard was the bellowing of two distinctly American accents. Both claimed to have fought in Vietnam with U.S. Special Forces and were there to train General Bo Jo’s recruits.

A few yards away, two pots cooked on an open coal fire beside what at first looked like a very large vine. On closer inspection, it turned out to be a freshly killed eight-foot python roasting in the coals. I sat down with General Bo Jo, the forty-eight-year-old commander of the 5th Brigade. The most active and largest of the KNLA brigades, it claims to have around 1,300 active duty men—who are under pressure from about 3,000 Burmese soldiers.

Bo Jo’s grandfather worked long ago with Britain’s Major Hugh Seagrim, known to the Karen as “Grandfather Long Legs,” who surrendered to the Japanese to save the lives of Karen villagers he was training. The Japanese broke their promise. Bo Jo began as a sergeant in 1982 and was promoted to general in 1997. Many senior Karen rebel officers have links with America and he was no exception, with a wife working on a Ph.D. in Indiana. In his mind, the struggle would last another five to fifteen years.

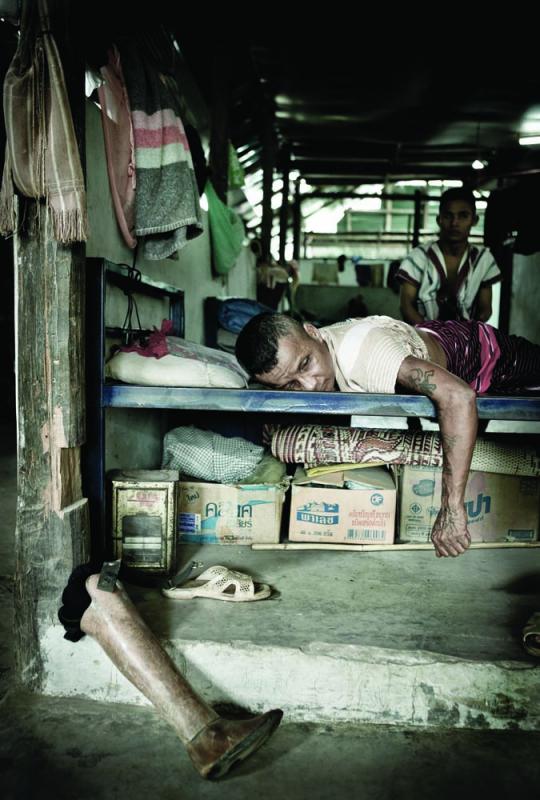

Bo Jo took us on a brief inspection of his Karen Special Forces soldiers. Their weapons included battered Vietnam War-era Colt AR-15s, some still stamped property of the u.s. government, plus a few bolt-action rifles and M1 Garands that appeared to date back to the Korean War and World War II. Most of the troops wore sandals or flip-flops.

General Bo Jo donned his uniform.

The distance we were trying to cover in two days on foot was about twenty miles; it’s a ridiculously steep route that was chosen to deter Burmese troops. Large holes in the bush were reminders of where even sure-footed pack mules slipped off the muddy trails and crashed down the side of the mountain.

At the end of the second day, after crossing a river aboard a bamboo raft and hiking over yet another steep hill, we arrived in a narrow valley at the training camps used by five-man local teams that then spread out across Burma to document atrocities and provide medical help. If an area was under attack, the young Karen men and women agreed not to leave until the last villager was safe. They would risk their lives and often die documenting and fighting. Without them there would be only silence.

The camp was in a deep green valley next to a boulder-filled river. Purple and black butterflies flitted past by day; cicadas chirruped. It was the start of the dry season. At night, frogs croaked. Stars exploded out of clear skies and cold air rushed in. The moon slid over the narrow valley.

The camp was small. A dozen huts with woven grass roofs held about a hundred young men and women. As part of their training, recruits learned to sing, tell jokes, and throw Frisbees—to lift the spirits of outlying villagers. Their weapons are whatever could be borrowed, bought, or scrounged. I saw less than a dozen M1s and AR-16s in the camp, and even those were rusty and recycled. Looking up at the gash of stars framed by the steep cliffs, the former colonel agreed that they didn’t really have a plan if and when the helicopter gunships came.

Before we left, the student soldiers surprised us by carrying us over their heads for fun and in respect, then covering us with ash and dirt—before throwing us in the river. It was a baptism of sorts.

![Most villages within Karen state are only accessible through a network of jungle paths. Supplies are carried in by porters, many of them young women who carry up to fifty pounds up and down steep mountain routes. Medical supplies, as well as basic necessities, are smuggled in from Thailand then trekked to remote villages.] Most villages within Karen state are only accessible through a network of jungle paths. Supplies are carried in by porters, many of them young women who carry up to fifty pounds up and down steep mountain routes. Medical supplies, as well as basic necessities, are smuggled in from Thailand then trekked to remote villages.](http://d1tdv5xoeixo5.cloudfront.net/sites/vqr.virginia.edu/files/story-main-images/pelton_01_opt.jpg)