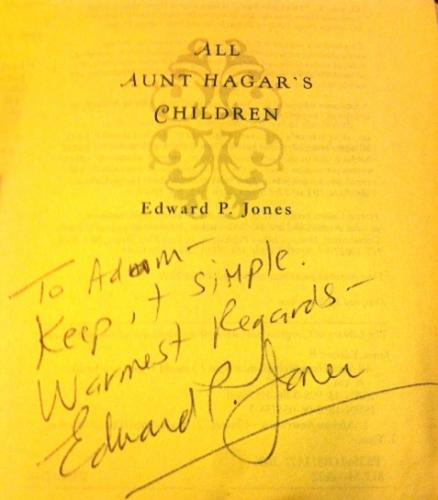

While I was an MFA student at the University of Wyoming, Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist Edward P. Jones came to do a workshop in one of my classes. The class met in a small, confined room with a long oak table you might see in a law firm. I had read “All Aunt Hagar’s Children” the week before and was blown away by what seemed to be his perceptive genius for character, the deceptive fluidity and ease with which he wrote. As I looked down at the story I had written for workshop, everything about it—the story, the characters, all the pseudo-literary embellishments—just seemed toy-like compared to his work. Maybe I was expecting from Jones some grave and sullen character like Sean Connery from Finding Forrester, but instead he talked about his favorite television shows, and asked if he could borrow a laptop so he could watch episodes of Breaking Bad on Hulu. Both in and out of class, Jones was a sincere and kind person, with none of the pretension I thought someone who’d won the Pulitzer, O. Henry, and the National Book Critics Circle Award might have accrued along the way.

To my individual session with Jones, I brought an overindulgent, overwritten story about a hurricane that had to do with loss and yearning. I did all the literary stuff I thought was unique: I made layers, withheld dialogue, described all the protuberances the mountains made in the late August heat. Writing the story took hours, but it made no sense. When I read it, it just made me tired. I’m pretty sure Jones had the same reaction.

To my individual session with Jones, I brought an overindulgent, overwritten story about a hurricane that had to do with loss and yearning. I did all the literary stuff I thought was unique: I made layers, withheld dialogue, described all the protuberances the mountains made in the late August heat. Writing the story took hours, but it made no sense. When I read it, it just made me tired. I’m pretty sure Jones had the same reaction.

Though Jones was gentle about the story’s deficiencies, it was clear he was frustrated. I think this was because it was clear to him that the basics of humanity shouldn’t be that difficult to express. He spent an hour and a half going over the story with me sentence by sentence. In the end, his advice was simple: “Just write a story.” After he said that, he leaned back in his chair and told me the story of Humpty Dumpty, as if he had to go all the way back to childhood and start there. “Look here, this is how a story goes. It’s simple. Humpty Dumpty sat on a wall, Humpty Dumpty had a great fall. All the king’s horses and all the king’s men…” After he went through his explanation he pointed at one of the sentences on the page and said, “Why did you write this sentence? What does it mean?” I said, “I don’t know, I was trying to be artistic, I guess.” He laughed, but not in a mean way—because I think he’s incapable of being mean—and said, “When you’re my age, then you can be artistic, but right now, just write a story.”

I remember driving home from the workshop and watching him walk down the side of the road in complete anonymity. The people who passed him had no idea who he was nor did they know about his literary accolades. He was just this dude who didn’t really care about all those awards and prizes. He was just a soul. I remember watching how Jones carried himself and saying to myself, “That guy is completely free of everything that haunts me in writing. He has nothing to do with theory, or academic gossip, or weird, uncomfortable dinners with squash casseroles, or any of that. The dude is like the ultimate punk rocker.”

I wanted to be like him, free, and I think my story in VQR, “Leon’s Fire,” was my first attempt at doing that.

When I write, I delete 75 percent of my stuff because I can imagine Jones’s finger on the page asking, “What is this character thinking? What would he/she say?” Writing for me has become trying to get inside my characters’ heads and figuring out what they would say. It’s hard. It scares the hell out of me because writing should be easy, and it’s not. I listen to people every day, and find so much to write about in their confessions, in what they say, but I struggle with weaving it together, with getting in close like Jones does.

“Leon’s Fire” is an attempt to get nearer to my characters, but it’s an opportunity I almost passed up. As an MFA student, I tried as hard as I could to avoid writing about fire and firefighting; I didn’t want that life to intrude on my fiction. I had been in firefighting for about ten years at the time and graduate school was a way to distance myself from that life. In workshop people were sometimes pigeonholed. There was the war guy, the rodeo gal, the Southern guy, the Montana guy, the postmodernist, etc. In graduate school, I didn’t want to be the “fire guy.” I wasn’t mature enough. My characters would slip into caricature, and the dialogue might serve some punch line, but not the character. The mountains had too many protuberances. The clouds had too many lavender streaks in them. I would take a character and run them through a chain of events and then look at the story again and ask, “Why did I do that?” Nothing I wrote mattered. After two weeks of writing, I would have a polished story that was nothing but air and pretty language with a character wandering aimlessly through it. I’ve smashed bottles in my kitchen and put fist holes in the walls trying to get it right. I’ve lost my voice screaming in my car while punching the windshield. I know this is melodramatic, but I wanted to get the story right so badly. I wanted to get to the point where the dialogue and story were flowing through me and I was just there at the computer experiencing it, without barriers between my characters and me. I wanted to be close to my characters like Edward Jones was. How did he do that?

Luckily, along came the character of Leon, who was based on someone I once knew on a Hotshot crew. I felt bad for him, but not until ten years later when I had a little perspective. All these years later, I still remember his battered face in the parking lot and the sad way he walked off the compound. He didn’t even have a car; he just walked, and I have no idea where he went or where he was going. But the character came to life when I imagined doing all that drinking and still having to run five miles every morning and then spending the entire day throwing juniper slash in the ninety-degree heat until nightfall. Then I thought of just being sick all the time because the only alternative was to face the bomb craters of divorce, child custody battles, and collection notices. The “Leon” I knew was tough to do all of that with mega hangovers. He had a messed-up childhood, a messed-up marriage—and he finished a forced death hike the squad bosses had for him, even with poop in his pants.

I’m going on to my twelfth season as a firefighter, four of which were on Hotshot crews. When I was a Hotshot, I was called a privileged “cracker,” not only because I was one of four white guys on an almost all Native American crew, but because I got to be a Hotshot for the novelty of it. I was in my twenties, with a college degree, bored, and got to choose what I wanted to do for money. Some of the folks I worked with didn’t have a choice. Poverty was the only option for many of my colleagues, a fact I tried to capture in my story. One crew member, at the age of thirty-two, was trying to save enough money to get his teeth pulled so he could get dentures. Once I drove the same crewmember to the pawnshop so he could get eighty dollars for his chainsaw just to make it to the next paycheck because he lost his commercial driver’s license on a DUI. He was the hardest worker on the crew. But, when I got sick of it, I could just leave and work as a Type 2 firefighter—which is merely seasonal work without the 24/7 schedule. I didn’t need the volume of fires the Hotshots (Type 1) had because I didn’t need the money. When I burned out, my response was, “Well that was fun, off to grad school.” When my colleagues burned out—and some of them did—they couldn’t leave the kind of money being a Hotshot pays. They had families, obligations, and relatives to care for. They ran fire after fire after fire, even though many of these men and women were in their forties. They had no choice but to stay on the crew because it was the only lucrative income available, since the closest metropolitan area was 150 miles away.

I hope I got the stories right of the people I’ve worked with. Most of the crew members I worked alongside are better than I will ever be, so I wanted to be careful about how I portrayed their lives. In trying to write this story, I even deleted a few months’ worth of writing just to make a character talk in a way that I thought was authentic. Before my rewrite I knew the character had no voice, but I knew he had something to say. And I was able to determine that the character had something to say because of what I learned from Edward P. Jones.

There’s something so honest in Jones the man as well as the people in his fiction. There’s also something calm, true, and unforced. Of course, it’s more complicated than “Humpty Dumpty,” but the reason he uses that example is to ask a writer to be honest with what he or she puts on the page. I hope I have gotten close to that honesty. Jones is quick to see through the nonsense and the stuff that doesn’t matter, because his soul is too wise, too big for it. I’m not sure he would like this story, but maybe I’m getting closer to what he was trying to get me to do in his workshop.

[Editor’s Note: Read “Leon’s Fire” by Adam Boucher from our Summer 2014 issue.]