1.

In the darkness it was nothing but a thin low thrum, moving to a higher pitch as it neared. The Goodyear Blimp was somewhere out there. I stared into the sky off Venice Beach, California, trying to locate the thing. A woman in a polo shirt (Goodyear blue) approached and pointed to a faint glow and dark outline directly above us. She was part of the blimp’s ground crew. “You know, this model is retiring soon,” she said.

Retiring, I learned, was a nice way of saying decommissioning, and decommissioning was a nice way of saying stripped and scrapped. Bits of it might show up in a museum somewhere, but that was pretty much it. There was one thing, though: a long final ride up the coast of California and beyond, twenty-nine days, 2,200 miles. “Would you like to come along for a leg?”

At the blimp base in Carson, California, about thirty minutes south of Los Angeles, I met Matt St. John and William Bayliss, blimp pilots. St. John, the senior pilot, had been flying the Spirit for nearly ten years. I asked him how long he thought the trip would take, some 170 miles northwest up to Santa Maria. “That’s the thing about blimps,” he said. Maybe eight, nine hours, all depending on headwinds. No promises, no bathroom.

The airfield was similar in purpose but different in kind than normal airfields—just a few acres of flat grass, with a big paved circle in the middle and a large pole to which the blimp was attached. Takeoffs and landings here were dicey. A breeze could come up and threaten to blow the blimp into traffic on the 405 Freeway or the large billboard by the road that boasted the blimp’s likeness, with the possibility of the actual blimp crashing into an advertisement for itself. The air in Los Angeles could be strange; it often got colder as you drifted toward the ground, instead of warmer, as it does nearly everywhere else. Cold air hastened the descent as the helium condensed, so instead of slowing as you land, you speed up. The point, Bayliss said, was that nothing on a blimp is routine, and nothing is a given, and that’s the joy of blimp flight.

2.

Bayliss and St. John disappeared into the gondola, swinging aboard up a small ladder as some of the ground crew steadied the craft. A dozen more men held ropes attached to the blimp’s nose. The loud drone of twin turbine engines started up. The gondola was small and simple: padded blue seats for six, pilots included. Nothing happens too quickly on a blimp. Liftoff wasn’t sudden or even really all at once. The blimp is always in the air, always mid-flight, so even approaching the 405 Freeway and all that rush-hour traffic, our drift to higher altitudes was slow and subtle. St. John worked huge, flat-foot pedals and a large wooden wheel alongside his seat, to raise and lower the small fins on the craft’s tail; then he pulled out a few knobs above his head, which released big bags of air within the blimp, allowing more room for the helium to expand, and punched the engines to give us some speed. We nosed up, pitched steeply, still moved slow—maybe twenty-five, thirty miles an hour, but I could feel my back press against the seat. I wasn’t buckled in and neither were the pilots. There were no seatbelts, anyway, and our windows were open to the air. Slowly, we drifted above gridlock, suspended below a huge blue bag of helium. We cruised toward the skyscrapers, the mountains, parts north.

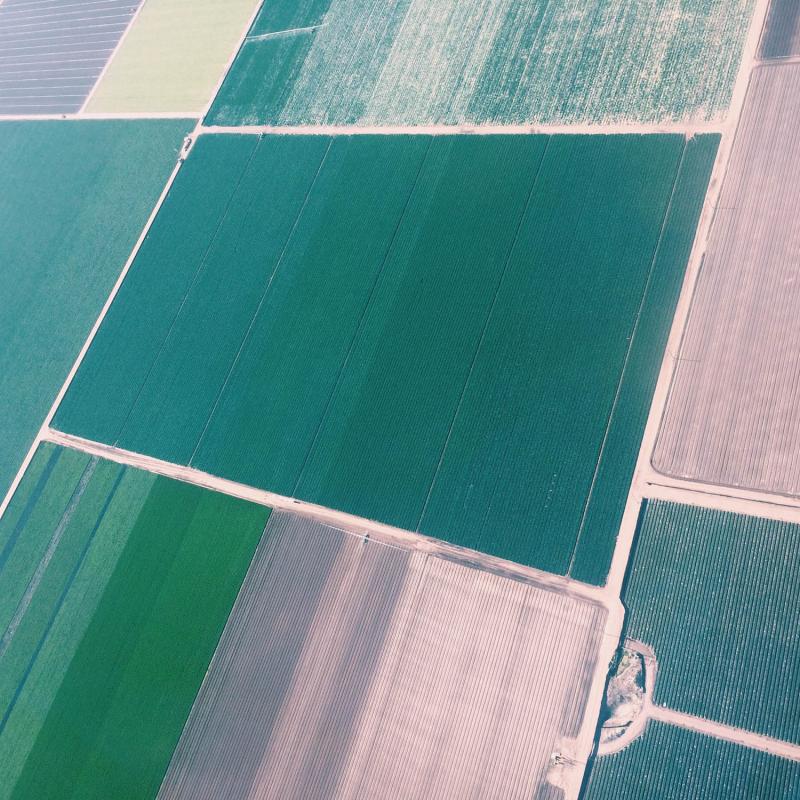

We leveled out about 1,500 feet above the freeway, kissed the edge of downtown and skirted along the Hollywood Hills, beating the traffic’s crawl and moving low enough to admire individual hikers, all stopped, peering up. The busy airspace above L.A. wasn’t a problem, St. John said, because “people see us way before we see them.” Yes, a blimp is bigger than anything else in the sky, and visibility, in this case, is the whole dang tamale, but not just for piloting. You’re Goodyear. You’ve got some tires to sell.

Nothing happens too quickly on a blimp. Liftoff wasn’t sudden or even really all at once. The blimp is always in the air, always mid-flight, so even approaching the 405 Freeway and all that rush-hour traffic, our drift to higher altitudes was slow and subtle. St. John worked huge, flat-foot pedals and a large wooden wheel alongside his seat, to raise and lower the small fins on the craft’s tail; then he pulled out a few knobs above his head, which released big bags of air within the blimp, allowing more room for the helium to expand, and punched the engines to give us some speed. We nosed up, pitched steeply, still moved slow—maybe twenty-five, thirty miles an hour, but I could feel my back press against the seat. I wasn’t buckled in and neither were the pilots. There were no seatbelts, anyway, and our windows were open to the air. Slowly, we drifted above gridlock, suspended below a huge blue bag of helium. We cruised toward the skyscrapers, the mountains, parts north. We leveled out about 1,500 feet above the freeway, kissed the edge of downtown and skirted along the Hollywood Hills, beating the traffic’s crawl and moving low enough to admire individual hikers, all stopped, peering up. The busy airspace above L.A. wasn’t a problem, St. John said, because “people see us way before we see them.” Yes, a blimp is bigger than anything else in the sky, and visibility, in this case, is the whole dang tamale, but not just for piloting. You’re Goodyear. You’ve got some tires to sell.

We leveled out about 1,500 feet above the freeway, kissed the edge of downtown and skirted along the Hollywood Hills, beating the traffic’s crawl and moving low enough to admire individual hikers, all stopped, peering up. The busy airspace above L.A. wasn’t a problem, St. John said, because “people see us way before we see them.” Yes, a blimp is bigger than anything else in the sky, and visibility, in this case, is the whole dang tamale, but not just for piloting. You’re Goodyear. You’ve got some tires to sell.

3.

The Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company started making blimps—both rigid and nonrigid—for the US Navy in 1917, up through the 1950s. (Rigid blimps are, technically, not classified as blimps but as dirigibles or airships, the Hindenburg being one.) After the Navy abandoned airships, in 1958, Goodyear kept up its airborne advertisements. In 1925, a Goodyear blimp was the first ever to rise under helium, not the usual hydrogen. The GZ-20 model we were in differed very little from the GZ-19 the company launched in 1959, and hardly at all from the first GZ-20s, launched a decade later. We were, St. John said, doing “some World War II–era flying,” and as he worked the pedals and cranked at the wheel, pulled the plugs out to rearrange the helium, it was hard to disagree. Ours was an atavistic journey.

A linguist friend once recalled for me phrases from a fast vanishing language. Montana Salish, she said, didn’t borrow any English words, and in ignoring even the most technical phrases created beautiful descriptions of the modern world—more true, in many ways, than the words they were meant to stand in for. “The car,” for example, was “p’ip’uyshn,” or “it has wrinkled feet,” for the tracks tires left behind. The phrase for “drive a car” meant “to make a domestic animal go straight.” Her point was that it wasn’t merely language people we were losing, but a kind of poetry. It was, she said, a poetry that tells us something about who we are, and where we were, and how we came to be. The blimp was like that too: a weird throwback. New blimps will be bigger and faster and quieter and in just about every measurable way better than the old blimps, but they won’t have a wheel by the side of the seat, or funny plugs for letting out air, or huge pedals; they won’t be as round or as friendly looking, or have such strange poetry to their inner workings. And they won’t technically be blimps at all. That’s sad, or maybe it simply is.

4.

It’s never a straightforward career choice, being a blimp pilot. There are fewer than 100 licensed in the world, and far fewer blimps to fly—less than two dozen. For St. John, an accomplished sailor, a blimp was the perfect combination of interests—a flying machine that acts like a 12,000-pound sail. A trip against the prevailing winds could prove slow and bumpy, much like rough seas.

One time, en route to Phoenix, the Santa Ana winds had brought the blimp to a standstill, extending the trip by half a day. “We could’ve flown to Australia in that time in an airplane,” St. John said.

“A lot about this job comes down to your mental state,” Bayliss added. “Can you share a cockpit with someone day after day, sometimes barely moving?”

Bayliss’s path to blimp piloting had been more straightforward: He liked how weird the job was, what a throwback the controls were, how nothing was routine. I asked if he was worried about the new ship, which would surely be more automated and fly-by-wire. He shrugged. It’d still be lighter than air, which meant it could still get tossed around by rogue breezes and strange temperature inversions. The unexpected could never be engineered away entirely on an airship; the air keeps it interesting.

Just then, an alert came over the radio. We were nearing the Navy base at Port Hueneme. The Navy was testing an unmanned helicopter in their airspace off the point and asked us to keep clear of it. So Bayliss, who was now at the controls, steered us off the coast toward Anacapa Island. Below us, the water was dark and calm. We could see several pods of dolphin working different bait balls, little patches of white upsetting the sparkling sea. Bayliss radioed the ground crew, who were driving up the highway to the landing site in Santa Maria. They were still well behind us (L.A. traffic) but, considering our current pace—a steady 37 mph and a long turn out over the ocean—would catch up soon. Tacking back toward the coast, we approached a thick band of fog, and would soon be flying blind through it. This was the kind of situation Bayliss relished.

5.

At Santa Maria, we circled the city for an hour, waiting for the ground crew to set up the landing area and raise the anchor pole. Two months later, St. John would fly the Spirit for the last time. For that trip, he brought along a special photograph, of himself as a child in Florida. He’s fishing, but not paying much attention to his rod or reel because there’s a blimp overhead, a Goodyear, the Enterprise 6. The Enterprise was decommissioned in the 1980s, but its gondola was repurposed many times, and is in fact the gondola for the Spirit, the same gondola we rode in over Santa Maria, the same gondola St. John would pilot for the very last time.

That day over Santa Maria he vacated the control seat and gave Bayliss the chance to take the blimp down, steering its nose delicately into the tip top of the anchor pole. It’s a complicated maneuver in the best conditions, and down near the ground winds were always shifting, and sudden gusts blew at all angles, causing Bayliss to crank at the side wheel and work the pedals, trying to steady the Spirit against the breeze. Again and again he narrowly missed the point of contact until, with a whoop, he stuck it, exhaling and delicately touching his finger to his nose. St. John slapped his back.

These dispatches are from #VQRTrueStory, our social-media experiment in nonfiction, which you can follow by visiting us on Instagram: @vqreview.